“For one scant day he had loved himself, felt himself to be unified and whole, not split into hostile parts; he had loved himself and the world, and God himself, and everywhere he went he had met nothing but love, approval, and joy.”

– Hermann Hesse, Klingsor’s Last Summer

In 1919, deeply affected by his experience in World War I, Hermann Hesse moved to Montagnola, near Lugano, to pursue painting. Here, in the Ticino region, Hesse began to emerge from his depression and wrote one of his most autobiographical pieces, Klingsor’s Last Summer (1919). This short novel narrates the final summer of a painter named Klingsor, who lives with restlessness and passion, and is particularly enchanted by nature — a nature that also captivated Hesse and inspired his art.

The Ticino landscape, which Hesse explored as one of its early tourists and where he lived until he died in 1962, inspired many of his watercolors on paper. Some of these — Rote Hütte (1922), Haus mit Turm (1928), and Senza titolo (paese con orto) (1929) — are featured in the group exhibition “Arcadia” at Bally Foundation in Lugano. Curated by Vittoria Matarrese, who collaborated with the Historical Archive of the City of Lugano and the Archive of Parc Scherrer, the show examines the transformation of the region into a bucolic attraction for foreigners in the first half of the twentieth century, making it the Arcadia of the title.

The exhibition begins with postcards from the collaborating archives, illustrating how the Ticino landscape and its perception changed over half a century. Early postcards from 1900–1930 depict alpine landscapes without roads along the lake. By the 1930s and 1950s, exotic trees and palms appeared — although these palms were artificially transplanted and not native. The opening of the Gotthard Pass brought many tourists, transforming Ticino from the “north of the south” to the “south of the north.” Wealthy German aristocrats bought homes and created gardens with palms, encouraged by the favorable climate. The city capitalized on this, branding itself as the “Swiss Riviera” or “Sonnenstube,” the place in the sun.

It comes as no surprise that the palm motif recurs in many of the artworks in the exhibitions, Gabriel Moraes Aquino’s Negative Palm VI (2024), a UV print of a palm he photographed, backlit by light projectors to simulate a sunset, nods to the palms of the postcards. Julius von Bismarck’s sculptures, I like the flowers (Bismarckia nobilis II) (2017) and I like the flowers (Pandanus utilis), small (2023), made from pressed and dried plants mounted on stainless steel plates, reference Western herbarium cataloging, ignoring the colonial history of the plant trade. Adrien Missika’s A Dying Generation (2011) pays homage to a 1970s book on Los Angeles palms, which were imported to Ticino. The dry, almost dead palms symbolize climate change and the failure of imported plants to adapt. Mehdi-Georges Lahlou’s Conference of the Palm Trees (2023) represents a palm killed by environmental issues, with molecules viewed under a microscope.

At the same time, the postcards also show how Greek temples, with their characteristic decorations, began to be constructed in Ticino during those years. This trend reflects the classical idea of Arcadia, marked by a fascination with ruins and antiquity. This enchantment with the ancient and ruins is fundamental in Marta Margnetti’s Wisteria Drops (2024), influenced by Piranesi, and Zuzanna Czebatul’s T-Kollaps (2019), featuring inflatable polyethylene columns in a green-painted room representing a temple rediscovered in the future. The columns deflate over time, symbolizing the fleeting nature of ruins: the ruin will be ruined. Vanessa Beecroft’s 2022 busts also echo the idea of Arcadia and Greek antiquity.

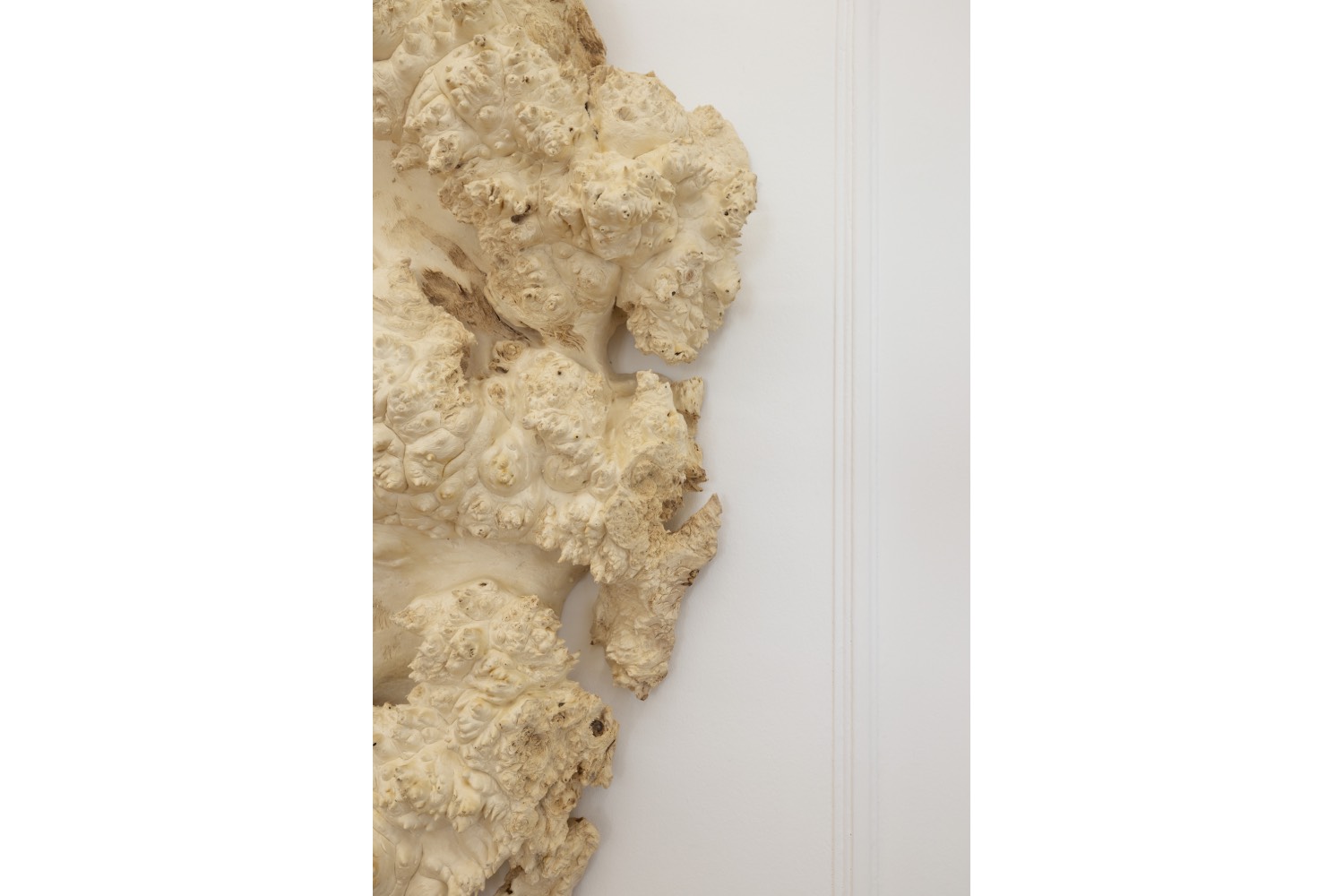

The artistic duo Ittah Yoda — comprising French artist Virgile Ittah and Japanese artist Kai Yoda — draw heavily from antiquity, occupying two rooms in Villa Heleneum. AVA (2024) is their most ambitious piece and the exhibition’s heart. Inspired by Leonardo da Vinci’s drawing of the human body on one side and a more “profane” mix of human and animal figures on the other, the statue’s color matches the villa’s staircase. Made from wax with pigments from marble sourced in Peccia and Arzo and mounted on steel, the statue was completed on site due to its complexity. Its alignment with a window overlooking the garden integrates nature into the artwork, making it intrinsically linked to its surroundings.

“Arcadia” fully engages with the villa, extending beyond the rooms to the staircase with Julia Steiner’s Produzione in situ (2024), a trompe-l’oeil vortex of garden leaves and plants in gouache. In the garden, 3D-printed glazed stoneware sculptures by Raphaël Emine, reminiscent of Aztec architecture, serve as insect nests in the trees; Vortex Reloaded (2020) by Zuzanna Czebatul, a spiral in opus sectile, mirroring a Roman intarsia, recalls Nicolas Poussin’s 1640 painting Et in Arcadia ego, a memento mori: you’re in Arcadia, but remember death. Located on the steps leading to the lake, Lisa Lurati’s Gazing in awe (2021) metaphorically represents the house’s eyes, guiding viewers to a magical Arcadia.

The exhibition transcends the villa’s confines, immersing visitors in the Arcadian landscape it celebrates. A few kilometers away, the church of San Michele, situated on a hill with panoramic views of Lugano and its lake, houses Phantom Orchid (2023) by Maxime Rossi, visible only through two small apertures. These UV-reactive serigraphs create a secret garden within the church — Arcadia within Arcadia.