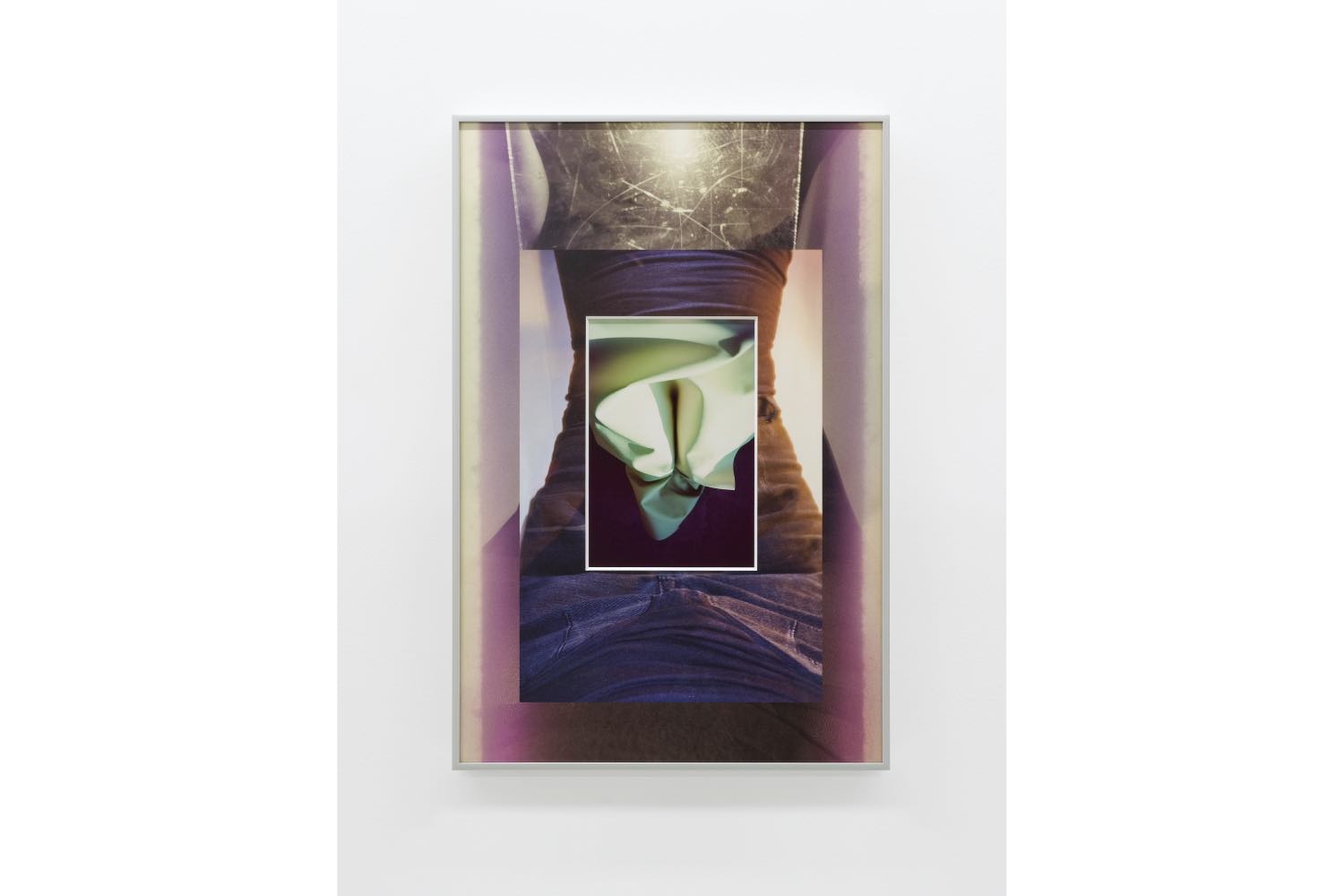

One image, slid. Something like cleavage, crumpled, diminishes into the groin. One image, synthesized. She is hard, interstice furling interstice, a puzzle. Subtext collects in the fold’s foil, crisp as sentence fragments. In this metonymical correspondence, nouns are driven from a preposition’s destined object, creased into obscurity. See legs open, become proscenium. See mirrors fluoresce, become retinal. See arms cradle, become parenthetical. Dashed to discarnate slices, (un)equal measures spark and smoke, her parts are rayed or slithered into obliquity: navels, fingerprints, the chatoyancy of a rarely sighted eye. Mannerism detaches from pose in this body beaded by avoidance. Irregular focus sees ellipses fingered, leaving us to perceive every pause. Gemmed with notice even through seeming absence. That’s the pull. And the kicker, too.

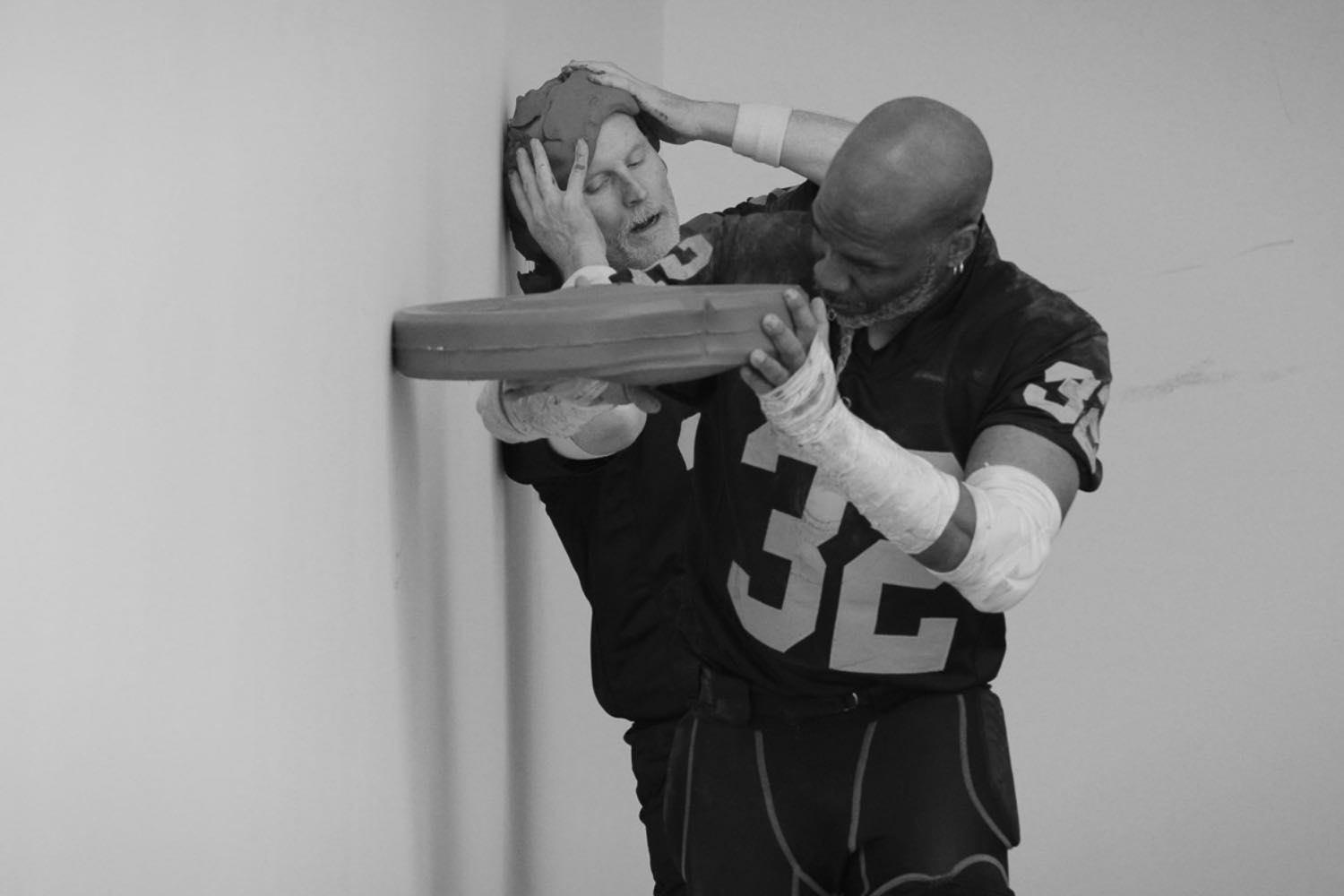

If punctuation is an apparatus for quick shock, lingering revelation, and much else, so too does B. Ingrid Olson’s work give proximity to suddenness. Her sliding incisions affirm a grammatical interplay even when works read more legibly as “photographic” or “sculptural.” Cavernousness, perplexity, introspection: these are the registers that give her limber use of photography, which insists on its adjectival elasticity, an ever-evasive presence. Through canny contortions and optical fracturing, collusions of technical precision and compositional disturbance see a carefully organized body at work in glimpses. Specifying her figure within the confines of her studio, Olson’s photographs yield capacity through embodied, formalist reflections on the mutual registrations between self and sociocultural space. This capacity, which includes sculptural, architectural, and textual expressions, engages relational studies of bodies, spaces, and visibility. Her reversals and refractions offer the possibility of comparison, interpolating shared experiences in the nether regions of perception and sensation. Postures assume plasticity, with every pressured position convergently rhymed with spatial details and optical antics in a language of explicit duplicity. All this is arrayed among a syntax of analytic cropping, hardcore flashes, and surrogate objects or materials — glass vessels, fine spun tapes, modeled prostheses — operative at times as works of partial self-quotation. But these agile tricks are always warmed by Olson’s hand, intensities of touch tempering her photographs with an admittance of fallibility that brings you closer still. Asking how many ways to combine her materials by the modest means of light, surface, depth, texture, and flesh, Olson recasts herself as a nexus of subject and object, material and device. Studiously distilled and dissevered, see how she tapers and tapers into cleverly immured indents, irresistibly auratic.

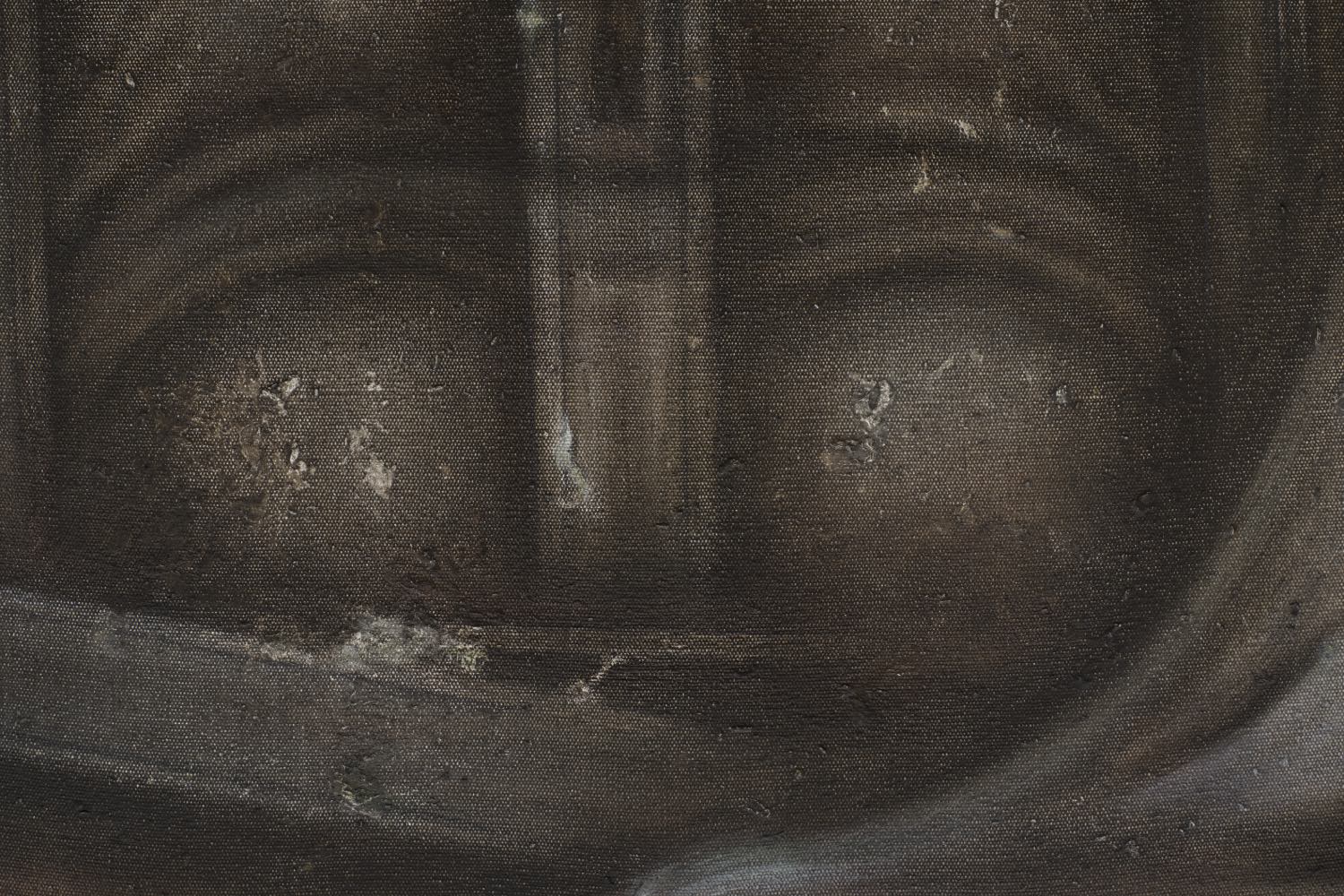

Lapped just so, she is both unfathomable frame and content. Canted viewpoints assert the primacy of an individual lens, through which we see, yet this directionality caves to abundant elision. In works such as Human Setup, Vertical Perforation; Harness and Ornament; and Perfect Spectator, perforation (all 2021–22), Olson’s nylon-clothed thighs are satiny braces for vitreous centers. Sighted as the site of flat yet full reflexivity, her tarnished mirrors prove unflinching reversals, serving to only restate your perceptual limits. In Clock and Sower (2020), Mutual Torso, with pants (2019), and Elastic X (2018–21) they are angled to interrupt the body’s unification and contest the photograph’s wish for composure. Mildly vertiginous, steeped perspectives redouble a sense of collapse as mirrors record the incandescence of a harsh flash in leftover flares. Lampblacks and silvers strengthen or slacken edgings while glossy exposures, sometimes greenish or glaucous, verge on an unbodied whiteout. A restraint and relaxant, light writes the photographs’ veracity as experiments in half-truths. Inner and outer limits overlap in her “Dura Pictures” series (2013–ongoing), where the surrounding frame’s mat board is itself inkjet printed, emplacing one image within another. Like parataxis, these images are rhythmed without conjunctions. X becomes a spot decentered by an unzipped fly; a pinkened cavity; an interleaved palm; a telescoped slit. X is a loophole that spells an inscrutable question. X is a backdoor that returns to you. Navigating the lip, she knows the erotics of intermittence, a twitchy seducement that refracts gendered gazes: spy the metallic strip that obscures her genitalia from below in !i! (2021–22). Where the “garment gapes” it is the flash “itself which seduces, […] the staging of an appearance-as-disappearance.”1 The dual contractions of Olson’s “Dura Pictures” are enlivened by her anatomizing strokes — fracturing, inserting, cleaving, concealing — expressed through multiplicities of envelopment and exit that collectively perform the works’ gap-ridden continuity. Disturbance is rescaled as though through the lens of sensation, like an eyelash, lodged in the eye, exudes an interfering and tearful extravagance. Clipping her fine-tuned subterfuge through corporeal, material, and visual ligatures, perception becomes affected as an awareness of looking. In this sharp relief, cracks excite tangency; candor invaginates camouflage; solicitation convenes smokescreen. Pocketing anonymized intimacy, Olson’s voids choreograph a pull and pushback that sets seeing on edge.

While intricately pretextual, the aberrations within these photographs are not the only means by which a kind of intersubjectivity is broached. In Hunger Candle, splintered (2021–22), Future Body (our) (2022), and the “Perimeter” series more broadly, the viewing of single yet disorienting photographs is delimited by deep Plexiglass boxes that regulate events of frontal viewing. As with her inlays, these extra-photographic tactics accentuate a sculptural and thus proprioceptive impact. This actual objectification of the photograph stretches the depicted interior experience out in tore flexive objects themselves.

Spanning nearly a decade, the “Dura Pictures” were anthologized as part of her solo exhibition “History Mother” (2022), which ran concurrently with “Little Sister,” respectively installed on separate levels of Le Corbusier’s Carpenter Center for the Visual Arts in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Presented as a retrospective of sorts, “History Mother” began with Proto Coda, Index (2016–22), a multipart sculptural installation that configured a sense of conclusion. Three perpendicular walls (that rise to Olson’s shoulders) displayed MDF reproductions of every sculptural relief Olson had made to date, inheriting permutations including Projection, Body Parsed (2018) and [M]others (2018–21). Through increments of meticulous process — drawn, digitized, carved, and cast — these eventually reduced and recessed forms appear as generational evolutions of Olson’s own anatomy. The sealed and smoothened depressions are distributed at the height equivalent to the bodily referent of either the installer or the artist, their placement thus altering with every new context. Summating a body in thirty parts that is itself arranged by the specificity of another absented body, Proto Coda, Index multiplies symmetries into generative dissensus. While Olson’s photographs are indeed indexical, in that they always point to something else, Proto Coda, Index is textually indexical, that is, of those words that are context-dependent and identify a speaker: you, me, here, now. Poised between abbreviating abstraction and elaborating figuration, these fiberboard forms evoke an iterative logic of open-source replication that can speak to, if not embrace, a you and me yet to come.

Where “History Mother” is reflective, “Little Sister” is responsive. Sequencing a “sheer overlay of new thought,” her spatial interventions apply a series of distortions and inversions within Le Corbusier’s masculinist architecture of cast concrete columns and floor-to-ceiling glass.2 Describing the space as “a dysfunctional, open camera with too much light,” Olson teases out the architecture’s affects and ideologies, sharpening the focus to calibrate her own morphological images3. Affixed to a column beside the entrance is one of two concave ornamental oblong forms. Uniformly studded with nipple-like protuberances, its surface flecked by hundreds of hairs, Common Animal, Natural Instinct (2021–22) is a puckered prosthetic that titillates the prospect of massage. Inside, the installation What I would be if I wasn’t what I am (n.d.) replaces preexisting light fixtures with adroitly modified 1930s pendant lights originally installed in the Ryerson and Burnham Libraries at the Art Institute of Chicago. 4Bulbs fully exposed, their sandblasted and powder-coated shades indicate petrified draperies, retracted claws, thirsted fangs, or labiated shells. The measured spacing of these wavelets catch the surrounds in scare quotes, their interjection of ornament pronouncing what was previously negligible with a slick riposte. Such mercurial maneuvers find a fervent rejoinder in White Wall, painted for Gray (2022). With subtle radicality, Olson overpainted one of Le Corbusier’s chromed red walls into quadrants of white tones in dedication to architect Eileen Gray’s French Riviera villa, E-1027. The work answers back to an erasing gesture of Le Corbusier’s, who covered the pristine palette of E-1027’s interior walls with eight vivid frescoes. At the center of Olson’s wall, she attaches Note, Gray (Kiss the architect on the mouth and paint a black stripe laterally across her forehead) (2018), a black-and-white photograph of her lipsticked mouth, teeth bared, clenching the suggestion of a ridged metal tongue.5

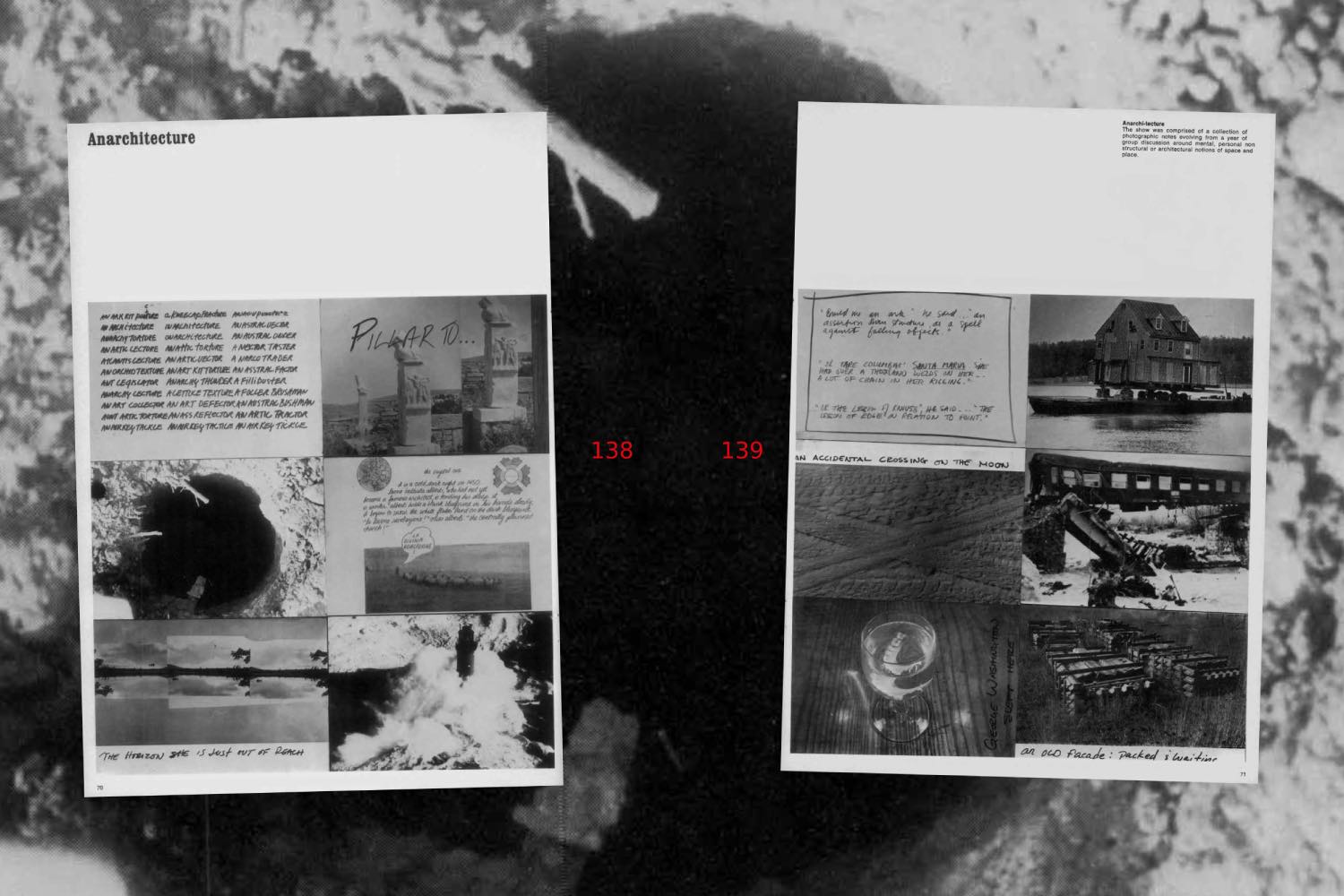

If a room “situates the cadence of habit,” Olson’s room is but a dormant camera.6 Such is her habit. Her studio is a room, a camera within a camera, that contains the possibilities of imaging, the possibilities of intuition. “How are we to understand the relation of intuition to habit?” Lisa Robertson asks. “They combine,” she suggests, “on the flat plane of the photograph.”7 Sensitive to precedents, Olson’s archival impulse will browse the outer reaches of her cosmology of forms, materials, subjects, and processes through freewheeling assembly. Metabolizing past work, she refigures their constitution, as we have seen, as kinds of reversions, evolutions, and generations. As intuitions are played out in Olson’s photographs, we might recognize elements not by their similarities or symmetries but by the very shape of their change. “We would like to gently expand the technique of intuition,” Robertson continues, “because it admits change […]. Intuition reveals the negative space of habit, carving an urgent threshold.”8 Things are taking shape, one might say of the nocturne series “Umbra” (2021). These tiny Polaroids (that are compiled in Olson’s publication 323) portray the takings of shapes as provisional intuitions — a palate, an ear — that carve faltering thresholds pulsing with caprice. The eye glides over these tiles of tentative balances and confidant bisections, the versatile shadows of saturations and wrappings; things of informational strangeness we can but approximate as a ductile mélange of annotative gestures.

As with her note to Gray, everywhere in Olson’s practice is the errata of citation, another shuttered lens that captures a fragment from a context. The auxiliary attraction of a photograph might function, for Olson, like an endnote — a quasi-textual aside reserved for future expansion. Similarly, and more recently, has the temporality of exhibition-making itself become material reserved for expansion. The year-long exhibition “Cast of Mind” (2023) at i8 Grandi, in Reykjavík, evolved through ten chapters, combining various works and materials to create “a hard copy out of something as slippery as thought” — making a habit of intuition, one might say.9 Akin to a workstation, Total Work (Cast of Mind) sites material reciprocities that later migrate to the layered board floor-work Total Work (Rest) (both 2023). This includes the freshened, oviform “Subject Position” series (2022–23) (also photographed in “Umbra”) in which embryonic or cranial cast plastic sculptures rest upon a leather brace or a scrap of velvet. The volume is echoed in the ninth iteration of the exhibition where a series of Polaroids, similarly framed and viewed in close succession as in “Umbra,” depict the circularity of a balloon inflating and deflating. Distending and puckering, the dilatory cadences registered in these images emulate the unstable shape- takings exemplified by the exhibition, their forms emanating, exhaling, and expiring.

Parsing Olson’s pauses is a task that apprehends her image-objects in the darkling chasms of stuttering description. “Description decorates,” Robertson writes in her revisionist treatise on Soft Architecture, whose malleable modus “greets shreds of fiber, pigment flakes, the bleaching of light, proofs of lint, ink, spore, liquid and pixilation, the strange, frail, leaky cloths and sketchings and gestures which we are.”10 This list of uncapturable sinuosity can be likened to the haptic “mental- clusters” that Olson describes in her psycho index (2020–24), comprising variously stapled minorities of matter: prints, tapes, fabrics, plastics, drawings, papers, and other nameless species of detritus. This index is intuitive and fragile, insisting on close reading that creates a torquing, proportional movement between a body and a psyche, snapping something back into us, alive again.

What shape, in the end, might we give these actions and reactions? An ellipse, perhaps. Elliptical paths are geometries that hold space for the adventure of thinking without codification or closure. In Thinking Space (2013), Robertson considers in the ellipse a provocation of geometry that proposes flowed knowledge and that propagates affect. “The ellipse is not a shape,” she writes, “but a temporality.”11 The ellipse is residual, resounding and returning to different thought-forms along its dangerous curve and irregular orbit. No matter how close, the ellipse embraces “the charge of a distance, a tension.”12 What do we see through the transitive tensions of Olson’s ellipses? We see that we can change…