Over the past hundred years or so, artists and scientists have come to follow increasingly common paths, from exploration to research to discovery, and from production to dissemination, first within their communities and then across broader society. As part of Flash Art’s ongoing investigation of contemporary practices, we reached out to Arts at CERN, an endeavor that since 2011 has been fostering dialogue between artists and physicists at the world’s largest particle physics laboratory. Flash Art Editor Eleonora Milani invited Mónica Bello, Head of Arts at CERN, to talk about the relationship between the arts and sciences.

Eleonora Milani: Where do art and science intersect?

Mónica Bello: Art and science meet at the junction between disciplines. Artists and scientists coincide in having the same drive to explore and understand what escapes our control — the shadows in our understanding of the complex world that surrounds us.

EM: Why was it necessity to find a place that could foster this encounter?

MB: The times we live in today are quite unprecedented. We have so much knowledge. We know so much about nature, and even our universe. We even know where our limits might be. They can even be detected and measured. In this context, it’s not rare that the hybrid areas between disciplines emerge as a helpful place to look for meaning and significance within a very complex panorama. Art and science have been connected in the past, but the interest that we are seeing in today’s culture is directly linked to our technological and information-driven society, which is defining the way we understand reality.

EM: Lately I’ve been reading Seven Years: The Rematerialization of Art from 2011 to 2017 by Maria Lind. It’s a very important time for visual art — I mean, for the world as well. Lind reflects on this return to materialization since 2011, asking, “What, then, of the artist’s hand?” The rematerialization Lind considers is not only related to the art object but takes in the wider category of contemporary art. It occurs to me that 2011, the year that Lind cites as a “new” beginning for artistic production, was the same year as the founding of Arts at CERN, which promotes dialogue between artists and physicists at the world’s largest particle physics laboratory. In a way, artists and physicists are similar because both try to understand the world, considering first the image, then the processes behind it. This return to materialism, in Lind’s sense, is not intended simply as a return to craft, but is metaphorical, referring to what can be done, under certain conditions, either collaboratively, independently, or in an institutional setting. I think this can be applied to the relationship between art and science.

MB: I think I agree with this. I arrived at CERN about four years after the arts program was created, in 2015. Since then my understanding of science, its language and key questions, and the laboratory’s dynamics, has grown to an extent that I cannot separate the focus of the research from the process of making science. It’s a unique time to be present at these kinds of laboratories, such as CERN, where so many people are involved in one single question, which is to understand the fundamental structure of matter and how our universe came to exist. Artists who come to CERN experience something quite extraordinary that shapes their general understanding of nature, and learn about the possibilities for reaching levels of cognition and sensing natural phenomenal in forms that were not imagined some decades ago. Artists engage with the material cultural of today, and science is an important element in this process, whether it is biological, ecological, or concerning any of the other media within the remit of the natural sciences. Artists, now more than ever, are “experimenters,” those who through detailed observation enact events that perform and devise the processes for new knowledge and enquiries to happen.

EM: Arts at CERN has sponsored a wide range of fully funded residency programs, which started with “Collide” in 2011, then “Accelerate” in 2014. In April 2021 you launched “Connect,” the new four-year program in collaboration with Pro Helvetia, that will expand to Chile, South Africa, Brazil, and India, starting with the South African Astronomical Observatory (SAAO) and the South African Radio Astronomy Observatory (SARAO). Can you talk about how you think about the art residency format and how it has evolved? I wonder if you see a potential to expand the format, which in the art world has become pleonastic.

MB: The residency model has varied slightly since the creation of the arts program at CERN. Artists are invited to the laboratory to research and explore ideas that connect with fundamental aspects of science and nature. This research was combined through the year with the understanding that art and science are founded in universal values, which everyone can share, and that both disciplines have the potential to form networks based on mutualism and exchange. In consequence our residencies follow this vision and offer different ways of participation. Collide was the inaugural residency, which consisted of a three-month residency at CERN, and today continues as three-year alliances with European cities. Linz, Liverpool, and currently Barcelona joined us, and each partner city hosts the artist for the last month of their residency in connection with some fundamental science in that context. Then, Accelerate began as a nationally focused program, with partnerships with organizations in different countries such as Korea, Greece, Austria, UAE, Croatia, Taiwan, Lithuania, and Finland. Artists from these countries were invited to spend one month at CERN. With Connect we opened a new opportunity to engage art and science at a global level. As a co-production with Pro Helvetia, the arts and science council of Switzerland, two artists are invited to spend time at CERN and later to travel to locations in countries such as South Africa and Chile, where there are important research centers and observatories dedicated to physics, astronomy and cosmology. Behind our residency programs there is a goal of connecting art and science as a rich and complex network, in which the dialogue between disciplines and the experience of spending time with experiments and researchers can foster new and more deeply informed cultural expressions.

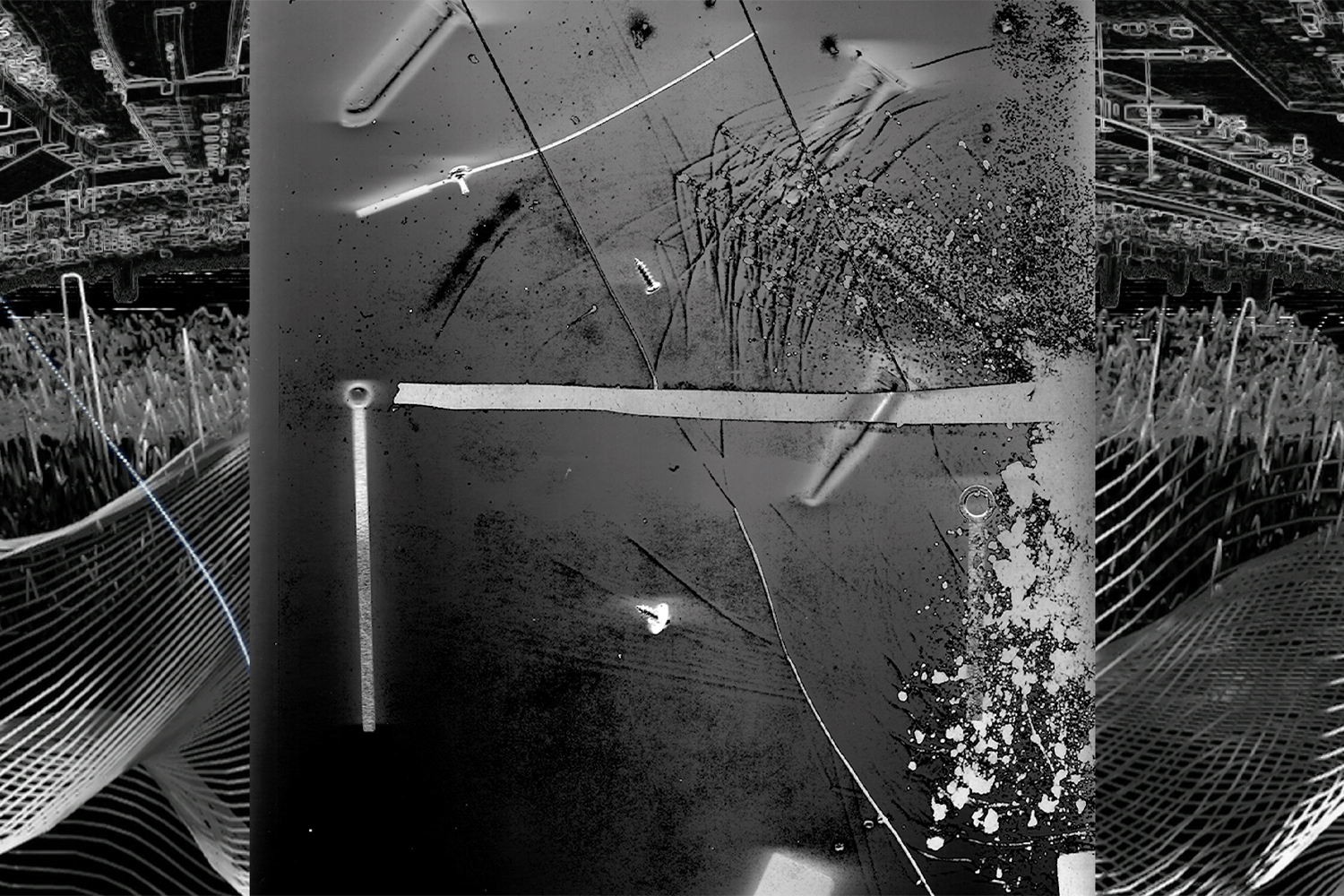

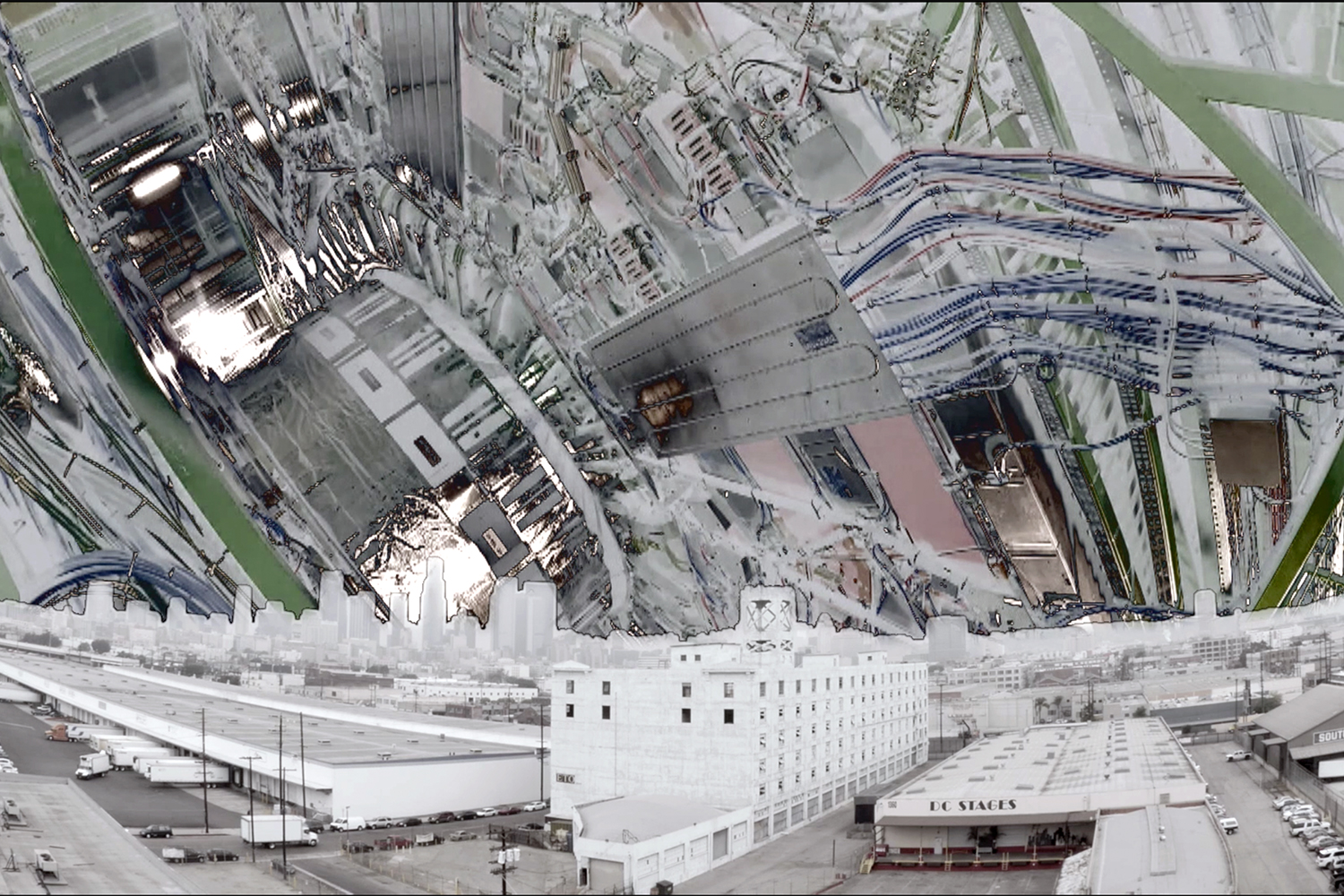

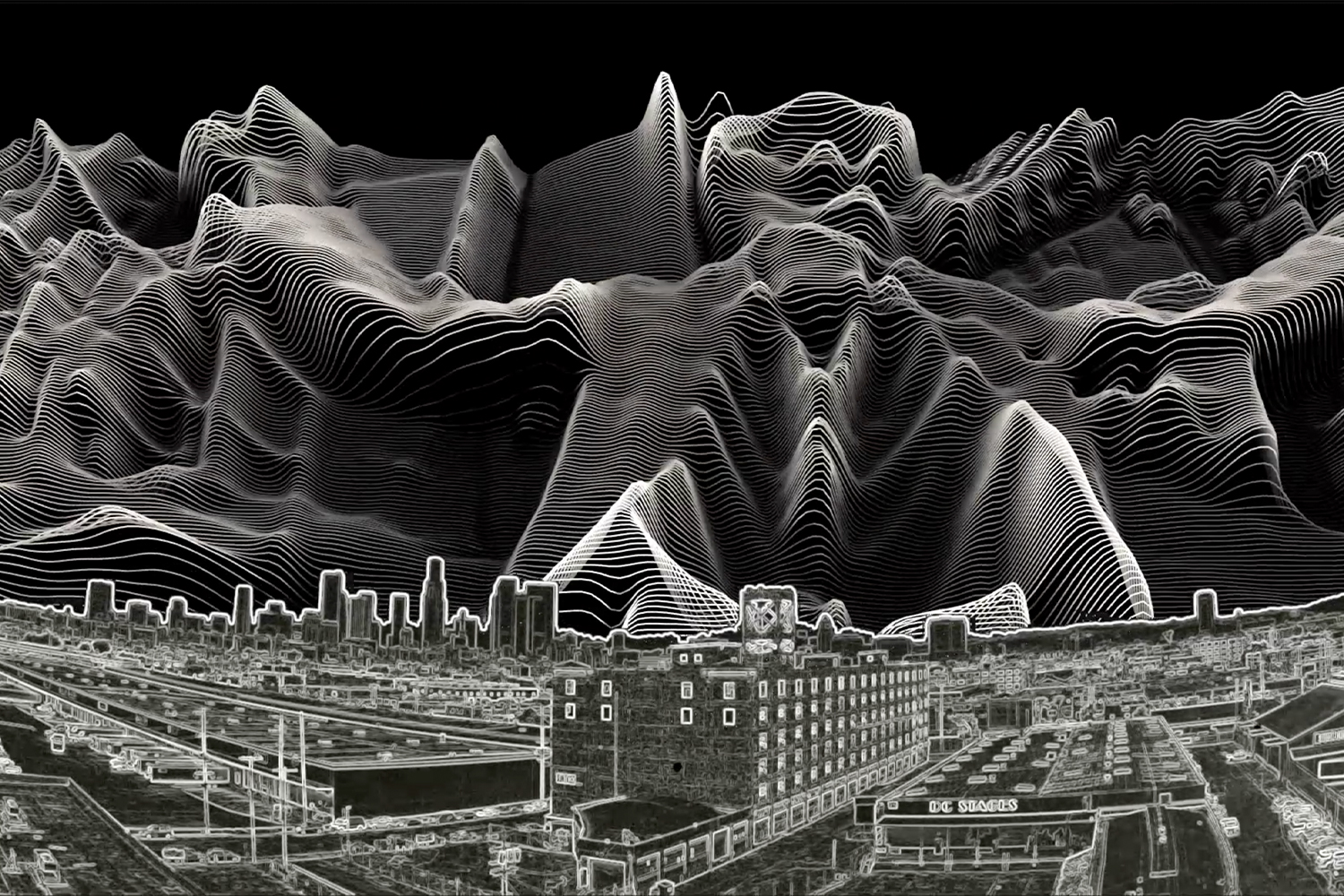

EM: Another important aspect, a tangible one that is literally the result of artists spending time in residence at CERN, is the artwork that is created. I remember when I saw Abyss Film, a sixty-minute collaborative film project by Leslie Thornton and James Richards, during the opening of the Biennale de l’Image en Mouvement in Geneva in 2018. I was impressed by the way the artists combined their moving-image practices to reveal hidden aspects of their work. That collaboration was the result of their residency at CERN in January 2018, and their observation that the largest physics laboratory in the world is in search of the smallest particles of matter. CERN started commissioning art in 2017. Can you tell us more?

MB: It was a very rewarding experience to support Leslie Thornton and James Richard. for the creation of their work for the Biennale de l’Image en Mouvement. Since then a new strategy based on the extension of the artist residencies into artistic commissions has been adopted, with which we aim to respond to the artists’ interest in continuing their research through an art production. The rising awareness of this type of interaction in scientific contexts by cultural institutions, academic environments, and the public made us consider creating a specific program dedicated to new commissions. Most importantly, the potential for scientists to see their dialogue with artists resulting in a tangible art experience became an important driver for us. Since then we have worked with artists such as Mika Rottenberg, Semiconductor, Mariele Neudecker, Haroon Mirza and Jack Jelfs, and Alan Bogana. We are currently supporting a new work by Richard Mosse, and soon we will be announcing new commissions with some other artists that are developing research projects in connection with physicists and engineers at CERN. Thus Arts at CERN is becoming an internationally recognized agency for supporting excellence in art and science productions in which scientists play an important role in the process.

EM: From the last open call in October 2020 you selected Black Quantum Futurism, a collective based in Philadelphia (US), as winner of the Collide Residency Award 2020. The collective will extend their research and produce a new artwork based on their proposal titled “CPT Symmetry and Violations.” Their research is mostly based on the concept of futurism, today at the core of cultural debate. Lots of artists are trying to imagine a future that could articulate a multidimensional approach to cultural production. What are your thoughts on that?

MB: Time and temporality are in constant shift and so is the concept of the future. The time scale that physics works with is far from human scale, and the artists find interesting sources in this field when trying to come to terms with how the reality of time and temporalities can be. The configuration of time and space have informed the work of Rasheedah Phillips and Came Ayewa of BQF for a few years, as it’s of crucial importance for them to create a context of critical thinking and to raise awareness of different temporalities. In a recent interview, the artists explain their interest in the design of practical tools which allow access to pasts or futures in a way, they argue, that linear temporality and obedience to mechanical and digital clock time does not allow. They will start their residency in September to further explore Black/Afro diaspora temporalities and the way traditions of time might share parallels with quantum principles. For their CERN proposal they have picked studies on CPT symmetry — charge, parity, and time reversal symmetry — as the fundamental symmetry of physical laws that holds for all physical phenomena. Through their residency and under the direction of Arts at CERN, they will connect with scientists, engineers, and staff at the laboratory to learn more about their investigations of time in physics, and to exchange with them perspectives that originate in social and cultural realms. After their time at CERN the artists will travel to Barcelona where they continue their Collide residency and research.

EM: If you could explain what CERN wants from contemporary artists, what would it be?

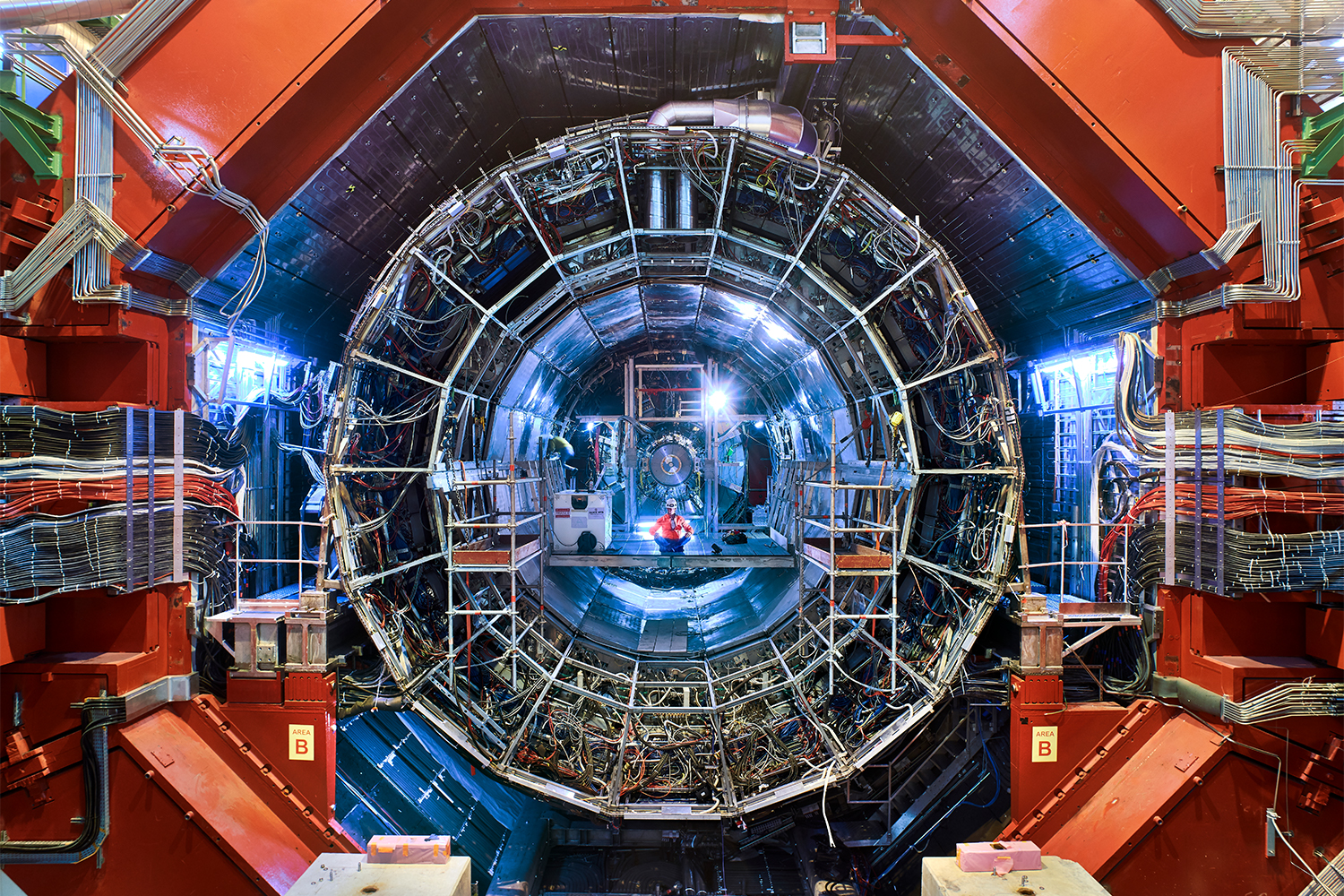

MB: Currently we find ourselves in a challenging but exciting time when a solid and dynamic infrastructure for sophisticated artistic research in scientific contexts is becoming established around us. At Arts at CERN the emphasis is placed on stimulating discussion around the nature of science and the notion of it functioning as a non-isolated practice. CERN is the largest laboratory in the world, and a place for fundamental science where advanced technologies allow us to enter the world of the subatomic, the hidden realms of nature that can only be revealed by highly complex and precise technology. Artists at CERN are welcomed at the lab to explore the challenges of imagining a multifaceted world as described by the lenses of science, which can also be informed by the lenses of art. Most artists who visit the laboratory and work alongside its community have never experienced anything like it — on entering the lab it immediately becomes clear that it will not be straightforward to comprehend the broad range of experiments, their scale and function. With our curatorial work, we respond to a model of institutional cultural practice that nurtures and support artists’ engagement with physics and hard sciences, and fosters research and production of deeply informed artworks.