Artists at Risk (AR) is a non-profit organization at the intersection of human rights and the arts, with a mandate to assist artists whose freedom, livelihood, and lives are at risk from politically motivated oppression and state violence. Set up by the curatorial platform Perpetuum Mobile (PM) in 2013, the organization has been collaborating with arts non-profits and government funders to assist artists who are at risk politically and fleeing oppression and war in locations all over the world. The organization has assisted many artists, including Pussy Riot members Maria Alyokhina and Nadya Tolokonnikova. The rhizome-like organization is constantly working toward building a horizontal network of safe havens for artists at risk around the world. Before the Ukrainian war, the AR network consisted of twenty-six residencies, the Artists at Risk Pavilions, and curated programs. The residencies are designed to offer temporary relocation for artists who are facing persecution because of the views they hold and express through their practices. In a time of unprecedented global upheaval and constant crisis, the founders Marita Muukkonen and Ivor Stodolsky are busy trying to coordinate a quickly expanding network.

Frank Wasser: Marita and Ivor, how are you today? I have a few questions to ask you about the structural framework of this organization. However, given the many rapidly unfolding global crises and the urgency of the current moment, it seems like there is so much to talk about, so much to resist, so much to act upon, so much to be done. What are you doing right now?

Ivor Stodolsky: We’re intensely busy with an extensive new network of hosts that we’re bringing together. We might start by explaining the whole structure. We basically have a web portal through which artists and cultural workers, and also hosting organizations, can apply. We currently have over 550 applicants from Ukraine, but also over 230 activists, anti-Putin — that is “dissident” — artists and cultural workers from Belarus and Russia. And then we have hosts. We have around three hundred hosting organizations which have applied to date via our forms. That is people and institutions wanting to help the artists and cultural workers applying to AR. Now, added to these direct submissions via our forms, there also are whole national networks of hosting organizations joining the process. Gradually, we are starting to work with these large networks, who are hiring curators to help with matchmaking: that is, to find suitable applicants to match with the suitable residencies in each national context. The Swedish network of residencies SWAN developed the model, placing a Swedish curator inside AR to help match artists with Swedish institutions. Right now, the entire Goethe-Institut

network of organizations in Germany is doing the same, which is a major step. The Danish network of visual art residencies is planning to do the same, as well as two Italian regional networks, and the list goes on and on. This trans-European cooperation is very important and exciting. Still, even though we reacted very fast, and are growing exponentially, it feels like the number of applicants waiting to be placed is always too long.

Marita Muukkonen: There is a new wave of solidarity now. The war in Ukraine is something that we have never experienced before at AR. We hoped that this kind of enthusiasm, care, and hospitality would manifest with other wars and crises. Because, to answer your question about what we’re up to right now, tomorrow we will again submit a list of Afghan artists at risk. We have different teams working at AR, and one of them, as we speak, is making a new priority list for the German government of Afghans at dire risk. We are appealing to Germany to firstly proceed to evacuate the applicants already accepted on their list, who have been waiting for far too many months. This list was arbitrarily frozen on August 31 last year, for no explicable reason. So, we are appealing to them to finally reopen the list, as has been repeatedly promised, and then to proceed with new visas and evacuations. We still have 450 artists at risk from Afghanistan on our list who need to be evacuated, which, including their family members, is more than two thousand people. Even the Afghan minister of culture is still in Kabul, which is appalling.

People from Ukraine can flee to Europe. They can go to some places without a visa, they can simply arrive in the EU without invitations, proof of income, promises to return home, etc. But when it comes to artists from Afghanistan, the first battle is to get into Europe, which is very, very hard. So, we continue our work on that. We are also trying to swiftly evacuate the most high-risk cases of Russian and Belarusian dissident artists, who likewise need visas to come to Europe. As we know, oppositional artists can face up to fifteen years in jail for their views in the Russian Federation. Some of our applicants have already gone missing and we can’t get in touch with them anymore. We are afraid that they have been jailed or worse.

FW: It seems like a lot of work that requires a constant set of conversations with many different people, institutions, organizations, and governments. Given the transnational aspect of your practice within AR, where are you working from right now?

IS: You’re asking about right now, in these very hours we are virtually accompanying a leading Russian dissident artist traveling from Russia to Europe. We are currently in Marseille, but we work from wherever we are. We have set up a residency here in Marseille and placed several Ukrainians within the wider region in southern France. Right now, we have a sculptor from Ukraine who has been taken in by Nice. The National Opera of Nice is going to stage a new opera for which this sculptor will be the main stage designer. Amazing connections are being made.

To give another example, we currently also have a Russian couple, both of which are violinists of world-famous orchestras in Russia. They found themselves stranded in Vienna, but now the husband’s visa ran out and we had to carry out an emergency temporary relocation to place him outside of the Schengen Area, in Serbia, to avoid him overstaying his visa and harming his future.

MM: Yes, many Russian dissident artists are coming to Europe on three-month Schengen visas and trying to find a way to stay. Many of them won’t qualify if they apply for asylum, because they have not spent time in prison — yet — or they haven’t been tortured or beaten to death — yet. What they need is art institutions which have enough resources to employ them, giving them legal ways to stay. And enough solidarity to create changes — that’s what they need. For example, the institutional field can apply pressure on their national policy, and, if it’s possible, to change, for example, the duration of Schengen visas to be longer for Russian dissidents, from six to twelve months instead of ninety days.

FW: It is interesting that your curatorial practice involves advocating for policy change. Can you tell me more about how all of this works regarding visas, and what changes can and must happen in order to help artists at risk really escape persecution and crisis?

IS: Sometimes artists don’t want to apply for asylum because it involves all these other potential problems. You basically lose your citizenship of your country of origin. Or you could be considered a traitor. If something else goes wrong, say you are rejected, it’s very much more difficult to go back. Often, you’re not able to work in the host country. The process can take years before it is finally cleared, and you can work in the country that you have sought asylum in. If you don’t have housing, you could be shunted into a camp in the middle of nowhere. And if you are slated to be deported, you could be a great filmmaker sitting in a camp on an island in northern Denmark, with an ankle bracelet, waiting for your appeal to be heard in several years’ time. It’s ridiculous and inhumane. So, with these dissident artists, we are hoping not only to get them Schengen visas, but to find a way to get them longer-term residency papers in Europe. Currently, the only way to do this is to apply for a work-based residency permit, and many European countries require a torturous application procedure that can only be done via the national embassy within the country of permanent residence. That needs policy change. It means, in effect, sending dissidents back into the arms of the FSB.

FW: At a time when so much of the global political landscape is in turmoil, the need for AR can’t be underestimated. You started AR in 2013, the period just after the occupy movement and the so-called Arab Spring. The world has changed a lot in that short amount of time. Can you explain a little bit about the context that AR arose from and how perhaps that relates to the moment you’re in now?

IS: We’ve been working together since 2007 as Perpetuum Mobile (PM). That’s still our umbrella organization, the legal entity behind it all. We’ve had many different projects, but we’ve almost always been working with oppositional artists and dissident figures. We could start by talking about initiating AR in 2013, but it would even make sense to go right back to the first exhibition we curated together: “The Raw, the Cooked and the Packaged – The Archive of Perestroika Art” in KIASMA (Museum of Contemporary Art, Helsinki, 2007), which was about dissident art in Soviet times. You know, we worked with anti-Putin people already at that point.

MM: Some of these Perestroika-era artists are now applying to our residencies. Some of them are even arriving in Helsinki next week. So those artists during the time of Perestroika are current Russian dissidents, those who must get out now.

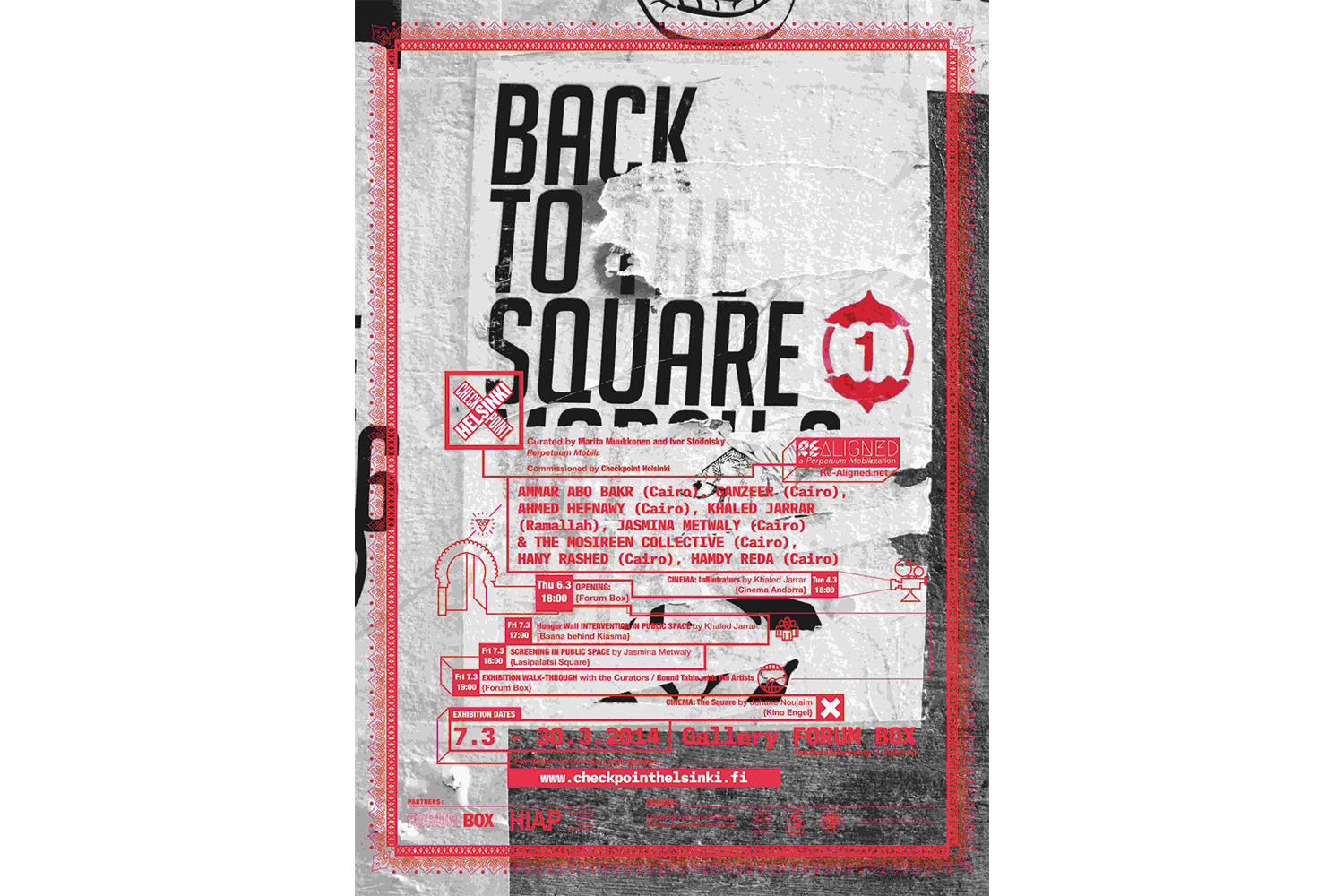

IS: It’s the generation that became prominent in the early 1990s — the children of Perestroika. It’s associated with a massive explosion of culture in St. Petersburg at that time. People like, for example, a rock star from one of Russia’s biggest rock bands, called Tequila Jazz, active in the famous Pushkinskaya 10 squat, who has just come to Sweden. These are the guys that we were doing things with in Russia in the early ’90s. But yes, we did that show in 2007 about Soviet art from this period stretching all the way back to the early ’80s. By 2013 we were already focusing on other areas. In 2013 to 2014 we were doing shows about the so-called Arab Spring and other rebellions worldwide during that period: “Back to Square 1” and “To the Square 2.” We did a lot of research in Egypt and Northern Africa. We worked with a lot of people who were part of the revolution in Egypt. People like the Egyptian street artist Ganzeer.

So, to make a long story short, we were curators doing curatorial research and we realized that, wait a minute, these people need to get the hell out. It was no longer a question of researching an exhibition. After the exhibition these artists could not go back to their home country. They simply would be arrested and tortured. We did our homework, and it became clear that there was no program that could help them. We decided that we had to do something for our peers. So we had to create a new residency program for artists of all genres that were under threat. AR was created because there was nothing quite like it in existence.

FW: Beyond the initial catalyst, how did this practice and project evolve? Did you foresee that this was going to go on and on?

MM: I think it has proved to be quite organic. When people heard about our work, more art practitioners at risk started to contact us, and then we realized that we had to do it in a more systematic manner. It is still at the same time our curatorial work; the core of this program is that we work with our peers: art professionals. We have a horizontal network of peers in each city that we work in. But as Ivor mentioned already, now with the Ukrainian war we have more than three hundred hosting organizations plus all these national networks that are joining us. And we’re always trying to set up new hosting hubs. Right now, we are trying to set up hosting hubs in Istanbul and other regional cities, because Turkey is one of the countries that Russian dissidents can go to without a visa. These places are important. Places like Tbilisi. We have a very active residency in Tbilisi, which has been working for a couple of years already. Since last autumn we have already been co-hosting four Pussy Riot members there. The space is run by former AR resident Giorgi Rodionov. This really highlights the horizontal nature of the AR network.

FW: What is the biggest challenge facing the organization at this moment in time? What aspect of your practice needs further support?

MM: Getting visas for people to come to Europe. The policy in Europe needs to change. We need arts institutions to work with us to apply pressure on governments. That is really the bottleneck. Following “RiskandRebellion” in Helsinki in 2021, and “Institutions and Resistance – Alliance for Art at Risk” at ZKM-Karlsruhe earlier this year, we are continuing with a series of symposiums and working sessions in Brussels, Berlin, and Bonn. We especially wish to also focus on helping Afghan artists at risk. Policy needs to be shifted to allow them to be entitled to a humanitarian visa, because artists — visual artists, musicians, filmmakers, political cartoonists — are at risk as a social group. We need governments in Europe to change their approach. There are murder cases in Afghanistan, there are torture cases, people are really being killed for being artists.

IS: Yes, people are being killed right now, just for being artists.