Art-world professionals are busy biennial-hopping once again. There’s the big one in Venice, the new edition of Manifesta in Pristina, the much-discussed Documenta 15 in Kassel, the Berlin Biennale, and even the twelve institutions of the photo triennial in Hamburg — all have opened their real doors to the real public. In other words, Europe’s biennial summer is on with a vengeance, notwithstanding the last wave of COVID or the next. Flight shame, however, can leave a stale aftertaste, so… Time for refreshments! ARS22 may not be the most remote northern art destination, but it is not particularly close either. Situated in and around Helsinki’s Museum of Contemporary Art Kiasma, this edition of the show features works by more than fifty artists, fifteen of which were commissioned by museum director Leevi Haapala and curator João Laia.

For Finnish audiences interested in art, the ARS exhibition series has been a window on the international art world since 1961. Results have varied, with editions from the late 1990s and early 2000s commanding attention around the world, and recent shows, which grappled with subjects like globalization, global- southern perspectives, and post-internet art maybe less so.

In this sense, the title of the current edition, “ARS22 – Living Encounters,” may sound vague, but it’s relatable: the idea of living together, of community, commons, democracy and how these subjects are reflected in cultural artifacts. Especially in the context of war in Europe, and Finland applying for NATO membership, no exhibition title comes without added weight. So what could easily gravitate toward the banal, the simplistic, or the populist — or be overintellectualized — here comes across via unambiguous motifs, and steers clear of any overt references to the current situation.

Take Sol Calero’s El Autobus (2019), a prop bus of the public transportation variety, painted in bright orange and mint green, with real seats from local busses used in Finland. You can get into the bus and see the show through its glassless windows. Although the bus won’t move, it’s still fun, and — bonus! — you can rest your feet a bit. It’s a simple and joyful piece, which can be experienced with a children’s playground-like naiveté, but it also describes a significant difference: who’s on the bus and who isn’t? Or, to divert from the idea of the magic bus of Ken Kesey and the merry pranksters: who’s on the bus and who goes to work in their own car — or private jet for that matter? It’s questions like these that come up when sitting in Viajes Paraiso (Paradise Travel). Whether you’re going to paradise or returning is not explicit, but I believe you’d know if you were coming from there. This is very much about everyday lives and dreams; even if Calero hails from Venezuela, via Berlin, the work feels remarkably akin to Helsinki, and refreshingly unlike any form of high drama or science fiction.

Speaking of which, Jenna Sutela’s lava-lamp heads have a very retro-science-fiction vibe. They are pretty much elongated, quasi-pinheaded self-portraits, self-consciously riffing on kitsch and narcissism. Illuminated blobs float around inside, pun- like visualizations of neuroplasticity, the imprints of subjective thought processes on brain structure: constantly moving yet unpredictable. A computer connected to each head translates the random constellations into sentences, which, in dialogue with the GPS positions of everyone who signs on to the artist’s “I Magma” app, functions as a daily oracle predicting our collective future. Thereby the online network of everyone interested in the project is likened to a longtime interest of the artist: the slime mold Physarum polycephalum. The unicellular but, in direct translation of its name, “multi-headed” mucus is known for its chemotactic behavior, which suggests a form of decentralized intelligence.

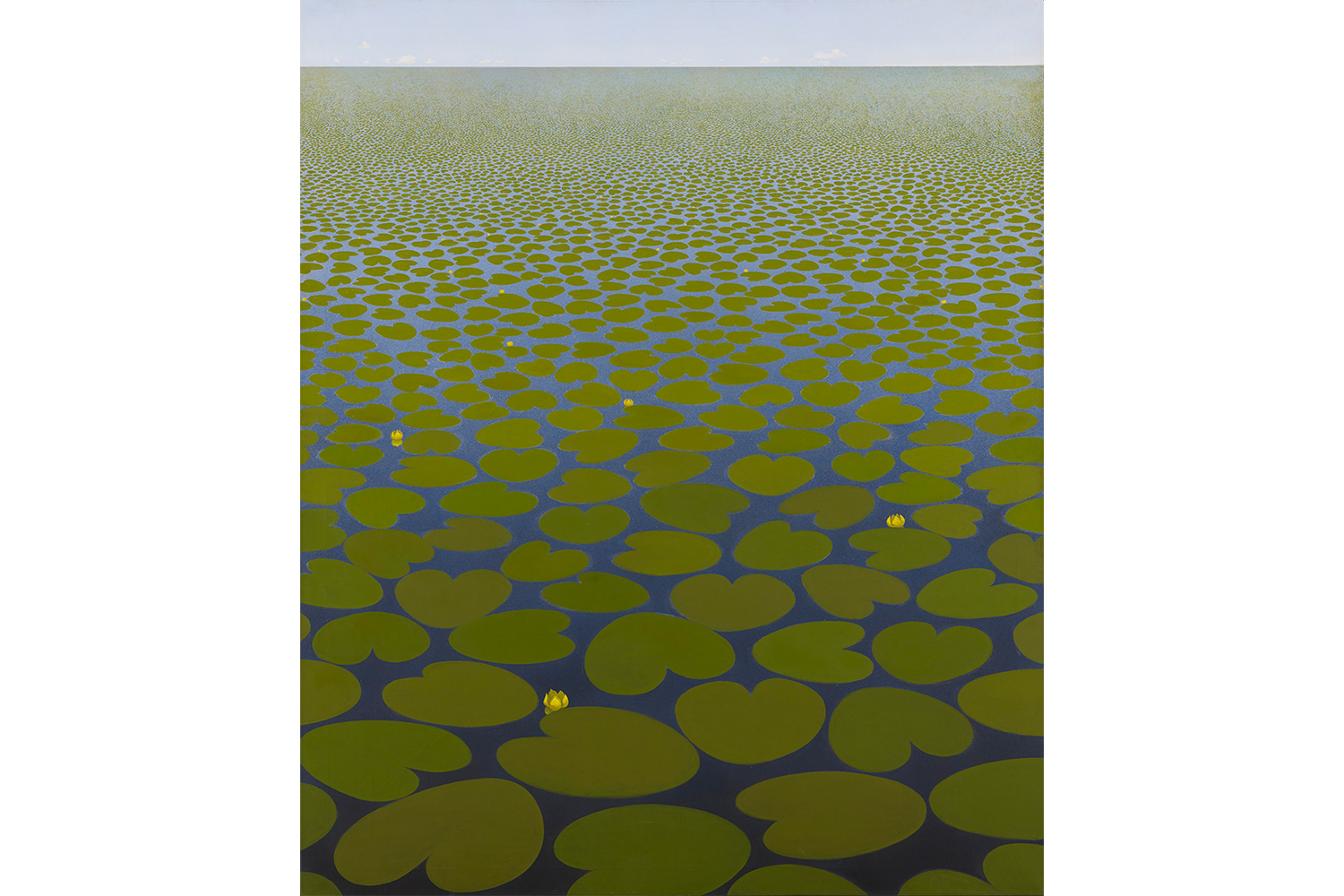

That the show leaves space to bring a position like this together with older works, like When the Sea Dies, a 1970 painting of water lilies expanding to the horizon by Kimmo Kaivanto (1932–2021, Finland), also presented at the 1974 edition of ARS, or an equally funny and painful video of Mervi Kytösalmi-Buhl removing bandages from her face (Plaster, 1978) is one true accomplishment, especially against the impressive background of works by hard-hitters like Arthur Jaffa, Frida Orupabo, Slavs and Tatars, Annika Eriksson, and Tehching Hsieh, to name only a few. The other accomplishment is a remarkable performance program running through the whole duration of the exhibition, like a performance festival in its own right, with prestigious productions including the Venice Gold Lion-winning climate opera Sun & Sea: Marina by Rugilė Barzdžiukaitė, Vaiva Grainytė, and Lina Lapelytė in mid-August, and a commission by the ever-surprising Dafna Maimon, whose Orient Express Yourself premiered last June. A film screening of Ima Iduozee’s Diaspora Mixtapes closes the show in October, when all that is left of most of the other biennials is a lingering aftertaste. Let’s hope our other problems vanish by then also.