Crises of language dominated the last years of both theoretical and artistic research of Aria Dean (b. Los Angeles, 1993). At this stage she explored thematic issues alternative to the traditional western model of subjectivity, that she perceived primarily through black studies, poststructuralist, media-theoretical, and accelerationist frameworks. Production for a Circle – staged at the Centre d’Art Contemporain Genève and existing as a video work – is part of a longer project that began with a play written and directed by the artist, Get-Together: A Tragedy of Language, which focuses more on a crisis of subjectivity. The action revolves around two young couples having dinner together and their progressive loss of self. In the following conversation with Andrea Bellini Dean addresses the crisis of art and its meanings, as well as the failure of accelerationism and traditional humanist frameworks.

ANDREA BELLINI: Aria, Wikipedia describes you as an artist, critic, and curator. Can you summarize what are, for you, the pressing concerns that need addressing within these roles today?

ARIA DEAN: Across these roles, I’ve recently been preoccupied with a possibly too-big question of what it is that art does, can do, or should do. I guess, simply, art’s capacities. This has been thrown into question repeatedly in the art world in the past few years, and I’m fascinated every time. I suppose I’m interested in this because, in my own practice, I’m primarily concerned with how meaning is constructed and circulated through materials and images. But returning to what is pressing, I think this question of what it is that we want art to do — not to say or to show — is crucial if art is going to survive its own existential crisis.

AB: You were born in 1993 in LA so you represent for me a new generation of black artists facing on one side black history and on the other a sort of twilight — making an effort to be optimistic — of white supremacy in the US. Can you please clarify how you feel about current US politics and racial issues?

AD: My feelings are complicated! Well, for one, unfortunately recent events here suggest that we’re in anything but the twilight of white supremacy; things are pretty intense. My most optimistic view of this moment — if we handle it deftly and swiftly — is that it’s the death rattle or dying gasp of a white supremacist order of things. Anyway, I feel like things are quite different now, in 2019, than they were in 2016, when I was first starting to write and show work, etc. I think in 2016 we were still in the midst of a Black Lives Matter moment in which a lot of American political and cultural discourse was trying to grapple with what it meant to be black in America — in general but especially considering the recent Obama presidency. In 2019, however, Trump’s administration has flooded the discourse. On the one hand, breaking the brains of shitlib-types who would like to embody all of the ills of American society in Trump himself and ignore the foundational history of violence and inequality in this country. On the other hand, the administration has advanced some very real, very dire circumstances — or awareness of circumstances — for not just black Americans, but for immigrants, for the poor, for queer and trans people, and so on. So I guess this is a long-winded way of saying that, for me at least, 2016 to 2019 has felt like a shift in vantage point. I’m still very concerned with blackness and the problem of being black in America, but maybe my scope is necessarily wider now. I think this parallels a general widening of scope in my own theoretical interests — I’ve moved from placing emphasis on investigating how blackness operates for itself, toward thinking through how blackness operates as a force among other forces. I’m interested in blackness as a specific object lesson — an object lesson theoretically (for instance: wow, a subject that is ALSO an object?) and politically (the dispossession that has characterized black life in America is not necessarily unique, in that capital would like to see everyone suffer just so. This is an oversimplification I admit! But you get the gist!)

AB: I see very well what you mean; the industrial revolution and the twentieth century have been a big tragedy for many people (also white), including religious, ethnic, and sexual minorities, especially in Europe. You wrote an interesting essay setting out a black perspective on “accelerationism.” Accelerationism is essentially the idea that capitalism should be accelerated instead of overcome, in order to generate positive social change. This theory actually goes back to Marx, Nietzsche, and later Guattari and Deleuze. Can you describe your perspective on accelerationism and how considerations of blackness might modify or otherwise affect it?

AD: Ah. So basically, the idea of that text was that accelerationism had fallen out of fashion and this was largely because Nick Land had become such an overly large figure in the discourse, and then the primary alternative later offered by Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams was so narrowed and whittled down to a practical series of imperatives that it kind of didn’t resemble accelerationism anymore. Anyway, I had been interested in accelerationism for a while and thought that there had to be another way. I identified that a lot of the anxiety around Land’s perspective — in its earlier phase, not later ultra-bigoted Land — was rooted in his anti-humanism. I was also reading a lot of black radical thought on humanism — Sylvia Wynter, Alexander Weheliye, and so on. And so, basically, I was like, “What happens if you cross-pollinate black radical thought’s critique of the human with accelerationism’s desire for a revolution against capital and assertion that humans cannot ‘defeat capital’ on their own?” A lot of this relied upon very granular retracings of blog posts by Mark Fisher, Nick Land, and Alex Williams just after the financial crash in 2008, in which they discuss that if one could accelerate capital to the point of self-destruction, some inhuman group-subject would be required to aid this revolution. It’s there that the intervention is made — very minor! If we look at capitalism as only ever racial capitalism a la Cedric Robinson and if we pull the thread that strains of black radicalism — some of this under the umbrella of afropessimism — unravels and dig into blackness rendering beings something other than human, then we can make the argument that that inhuman agent could be the black subject.

AB: The inhuman agent might not only be the black subject, as we were saying before.

AD: Yes, I think that the major theoretical maneuver I’ve been trying to manage lately is arguing that it’s the conditions of the black subject that could make black people this inhuman agent, but that others could exist under those same conditions. In some ways it’s an overarching argument for rethinking how we view ourselves as human agents, how we understand our own humanity. Remaining attached to a Western philosophical construction of the subject is a drag. And this is outlaid even by people outside of the black radical tradition, like Deleuze and Guattari, Spinoza, even like Schopenhauer in a way.

AB: You are very articulate as a writer. I was wondering, do you feel any frustration when, for example, you make art? When you make an object, let’s say, out of clay for an art gallery?

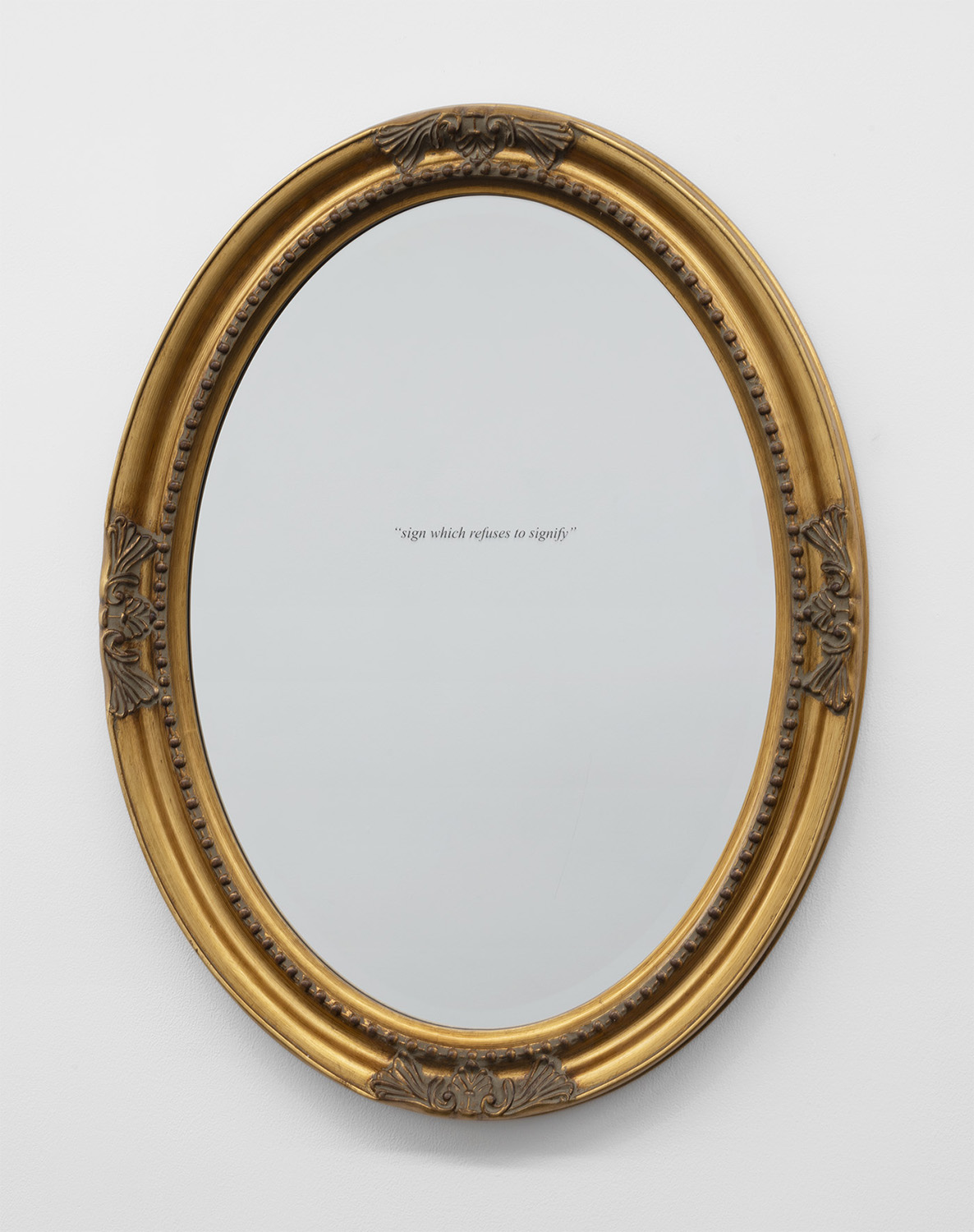

AD: No, I don’t feel frustrated, or at least not in terms of my capacity to articulate myself. For one, I don’t believe in engaging art as an act of articulation. Clarity, to me, is not the goal. So it’s really a different set of muscles that I’m exercising when making things — much more poetic than hermeneutic. I do feel frustration in that, while I am operating in that way, many viewers or visitors are expecting an object to tell them something. They want art to either articulate its own reason for existing right there, or articulate something about the artist or the world. This is boring to me. And I suppose as a good writer, maybe people expect me to make work that operates along the same lines as writing. But why would I do that? The whole point of doing both is that they offer different things!

AB: I agree. The problem is the danger of being literal. To be honest, I feel a risk in applying my own preconceptions to some of your pieces. I don’t really like being in that position, but it is unavoidable I guess. For example, let’s talk about A Regular Thing (2017). Here you use cotton, and cotton “tells me something,” to use your expression. I imagine you might be interested in this material for your own reasons, but cotton — used the way you do — makes me think again about blackness, and maybe jail, and maybe rap. Which is ok, I kind of like it. Though what I’m trying to say is that the risk for an artwork resides in being over axiomatic and self-evident. In this sense my favorite work of yours so far is Production for a Circle (2019). I like it for several reasons, the main one being that you reach something more universal and maybe more abstract through it. Can you tell me about this work?

AD: This play came out of my frustration with art-world discourse in a way. Initially it was meant to be a sort of language game, taking up phrases and tics popular amongst the left-leaning millennial culture-monster set. I wanted to surrealize that language, and kind of grind the discourse up into the meaningless chatter it always already is.

But also for a few years, I had been doing all of this writing and work about the dissolution of stable subjecthood, and the dangers of fixing oneself in an identity — danger in that fixity is an illusion, this idea of a stable self (whether you’ve actualized and reached it or are trying to “find” it) is a fiction, and also in that fixity offers you up to state actors and private interest blah blah a neoliberal technocratic order of things. Anyway, I wanted to write about these four very “average” young people losing themselves. As I wrote, it became more about this than about the language games. The language unraveling is just a way to get at the self-unraveling.

In this iteration of the project, which is the first time all four actors are white — previously there was always one black woman actor playing B — the play gains a new valence. I’m still working through what this means to me, but so far it’s interesting directing four white actors in something like this, where the goal is to dissolve them essentially. To me it’s like taking these proper Western subjects and inverting them, or smearing them across the stage. This could be sort of violent, but I think it’s sort of gorgeous. As one character says, “I’m nothing, I’m no one, I’m everyone, I’m dead!” That’s sort of the aim overall, to run this simulation that leaves everyone voided. It’s not a sociological statement, but a metaphysical inquiry.