Arthur Jafa: Ok, we’re at my studio in LA. [laughs] Where do we start?

Anne Imhof: I thought we’d talk. I mean, for me it’s so great that you’ve seen the work.

AJ: I saw “EMO” (2023). I saw, of course, “Natures Mortes” at Palais de Tokyo (2021). I was really curious, because I’d just seen images and read about it. I remember asking people, “What do you think?” Particularly after I saw “Natures Mortes” in Paris. That’s where we first met. Well, actually, we first met on Zoom during COVID-19.

AI: Exactly.

AJ: I was in Paris for the Cahiers d’Art installation.

AI: Yeah, right.

AJ: Someone said, “Anne Imhof is rehearsing. You want to go by?” And I was like, “Fuck yeah.” And we came by, but only hung out for an hour because we had to catch the train. And, like, “Wow, that was incredible. I’m really curious see it full on.” I flew back to LA but turned around and returned [to Paris] four days later.

AI: Yeah, I remember getting your SMS. I was excited for you to come back to Paris and kind of nervous about the piece. I was so hyperexcited I had stage fright — this hyper state and nervousness all mixed up. The show was a huge deal for me, and I worked day and night. It took me two days to answer.

AJ: I have a video of you that’s, for me, so

emblematic of how I understand you. Because I walked in, and you were very focused, moving through the crowds, studying different parts of the performance with your team. I saw you staring intensely at the performers. I just pulled out my phone and I started videotaping you without asking or anything. And it’s almost like you felt it and you went like this [turns and looks over his shoulder] “Who is this videotaping me?” You looked over warily and then you just smiled. We’d talked beforehand a bit, but that’s my first hard impression of you — this flux between a severe, almost disassociated focus and surprising warmth.

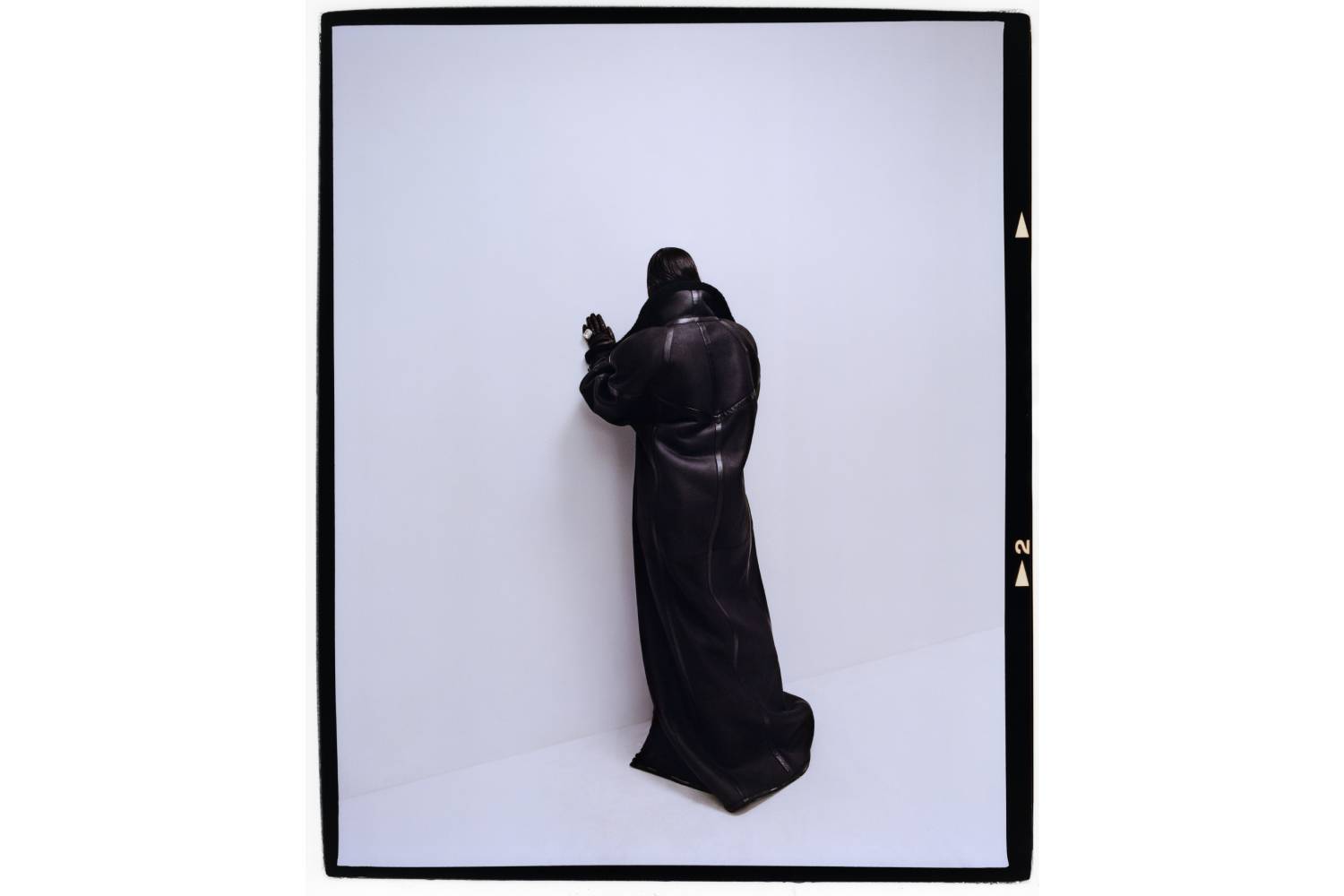

AI: It’s a condition of being on both sides of the spectrum. Being, like, super hyper, super low. That’s my thing, I think. But I feel it in what you say, the expression. Eileen Myles once wrote this text about me, that I was “slinking around looking

worn and radiant… a sort of zealot… looking like a medieval cult leader.”

AJ: Yeah, you were super, super focused. The question I had from the beginning, and the question that arose a lot when I asked others, “Have you seen Anne Imhof’s stuff?” You have to know your work is polarizing — as, in my opinion, all work should be. One of my biggest questions, really an ongoing question — if not lament — regarding my own work is, like, I don’t feel like I have access to much pushback against my work. And people have

told me, “Oh yeah, there’s pushback.” So perhaps it’s just a consequence of people not sharing their pushback. But regarding

your work, I think of it as, on one hand, being as celebrated as anything could possibly be now, but also people have strongly

ambivalent opinions about it. There’s very little in between. “Eh, it’s all right.” There’s very little of that. It’s either “the most amazing thing I’ve ever seen” or “I hate it,” and oftentimes when I’ve interrogated people about it, when I’ve said, “I think it’s amazing,” folks be like, “Eh, I don’t think so.”And I say, “Why?”

They’ll essentially do an inventory of the very things that make it amazing, contemporary, powerful. You know what I mean? It’s like you’ve created a zeppelin and people are saying, “It’s not grounded.” And, like, of course it’s not grounded. It’s a fucking zeppelin. You know what I mean? Like, precisely. That’s the point. The critiques are localized around the very aspects that mark the work as being both so evident and transcendent. And yeah, there are some overt thematics you return to, like disaffected youth or perhaps just youthfulness. What’s that about?

AI: It’s about the transition moment or body moment.

AJ: Body?

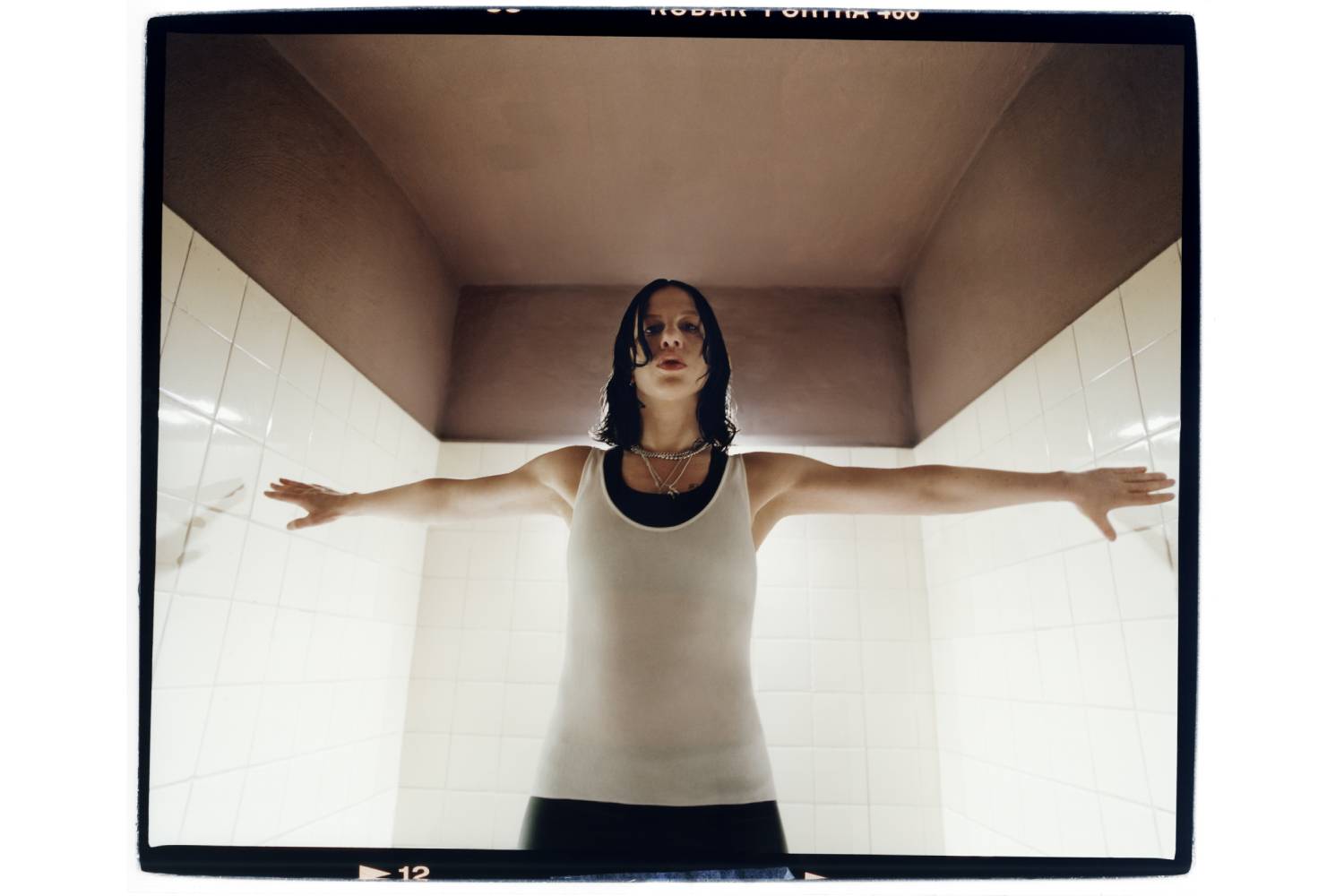

AI: Yeah. It’s concerned me since I can think. This was never a given thing to me. I did not have clarity about what it actually is, a body. The body and how it’s seen, where it begins, how it changes, and what box it is put in by others.

AJ: What its boundaries are.

AI: Yeah, exactly.

AJ: It’s really fascinating. I’m like, “No, that’s what’s genius about it.” Folks don’t understand how hard it is to make a thing that has fuzzy boundaries. It’s very, very difficult to make a thing that doesn’t arrive already predigested. It’s a consequence of where we are in history. We’ve read so much. There are so many books, so much social media, so much information about things, one seldom has an opportunity to experience anything without a preformed, categorical opinion about it.

AI: There are blurred lines, yes. What you describe is exactly what I’m trying to do. There are layers of meaning in the images. And the images are many. Crystalized.

AJ: Even when you say “images,” I think it’s important to point out: not pictures. You deal in pictures as a material artifact, but you’re also manipulating images that are not

necessarily pictures, which is —

AI: You mean, fixed?

AJ: Yeah, a photograph is a very particular sort

of materialization of an image. But to be able to create a fundamentally immaterial artifact, that’s generating images without a material frame. It’s an image that’s being generated in real time in front of the viewer. A photograph is a very particular sort of materialization of an image. But to be able to create a fundamentally immaterial artifact is an instantiation of an image without the material frame. It’s an image that’s generated in real

time, in front of the viewer, and minus aspects of the inherent morbidity of the photograph.

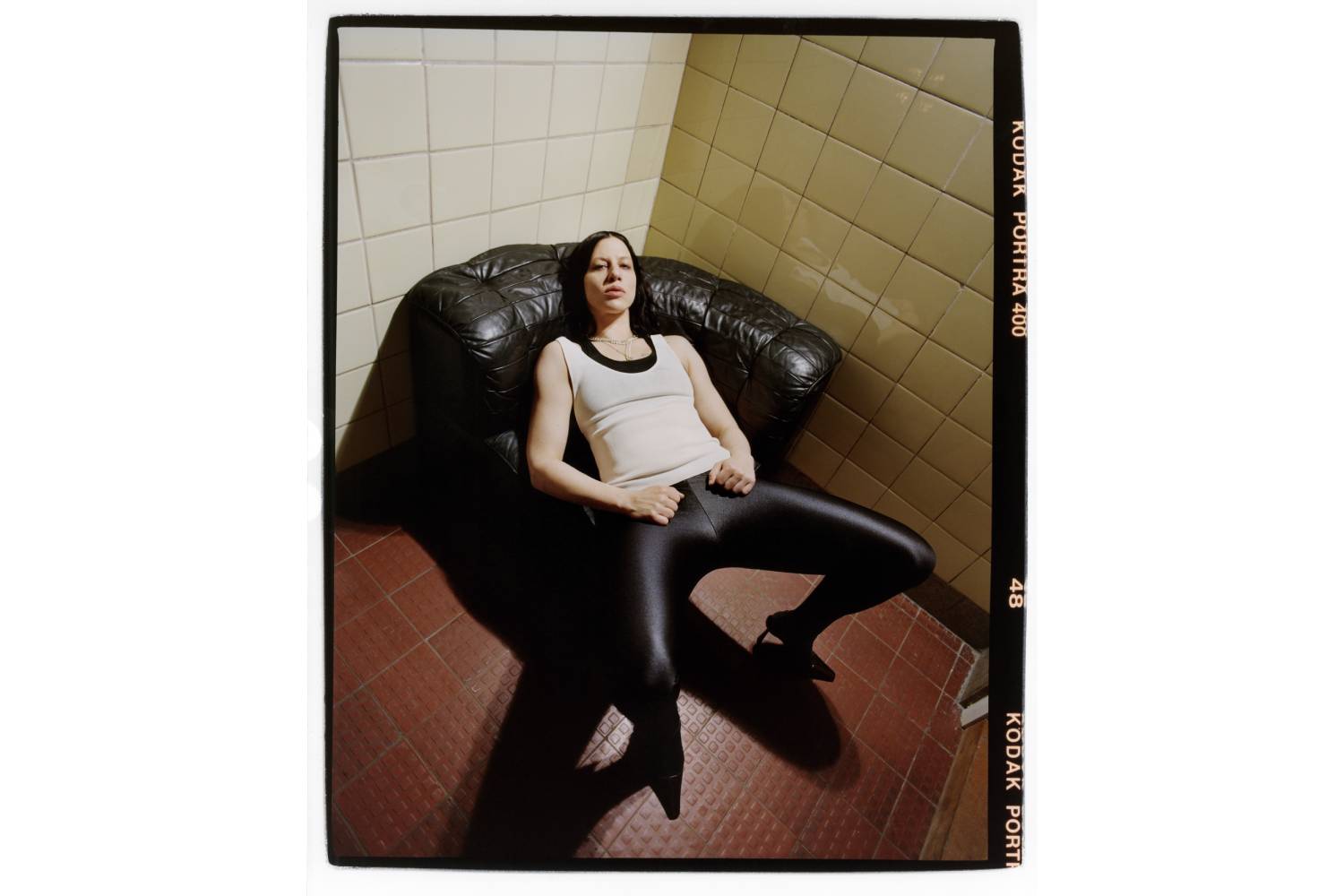

AI: And with the viewer as well. It’s this exact moment. The live. It’s the most magical thing for me. Being in the same space with everyone, the performers and the audience. This is why I love being a performer. In this moment everything seems possible. There’s a transgressiveness in it. Not

acted out for real, but it’s there. Whenever people are together,

and their energy sums up, they are able to do anything. It’s threatening and soothing at the same time, because there’s so much potential and hope in that. At the same time, it could be violent. It could be destructive.

AJ: How’s there hope in it?

AI: Because people can change stuff. All people could be saying the same thing and make it sound louder. It’s a super simple thing. They could move towards one direction. They could push every wall. When I did my first pieces, Angst (2016) and Faust (2017), I was like, WOW, we’re in the same space. It was blowing my mind. Then I was like, WOW, we breathe the same air. WOW, we are staying in here and all our hearts are pounding. All of those people in here are alive. And then I was like, “Oh my god, this is my dream.” There’s no future. There’s no hope for a better world. There is only hope as such. There’s always a past, but it might be or might not be relevant right now. This is what I can create. And it is never a finished thing. It’s always in transition. It’s always fluid. I felt that I’m safe on stage when people are looking at me — people that I don’t even know.

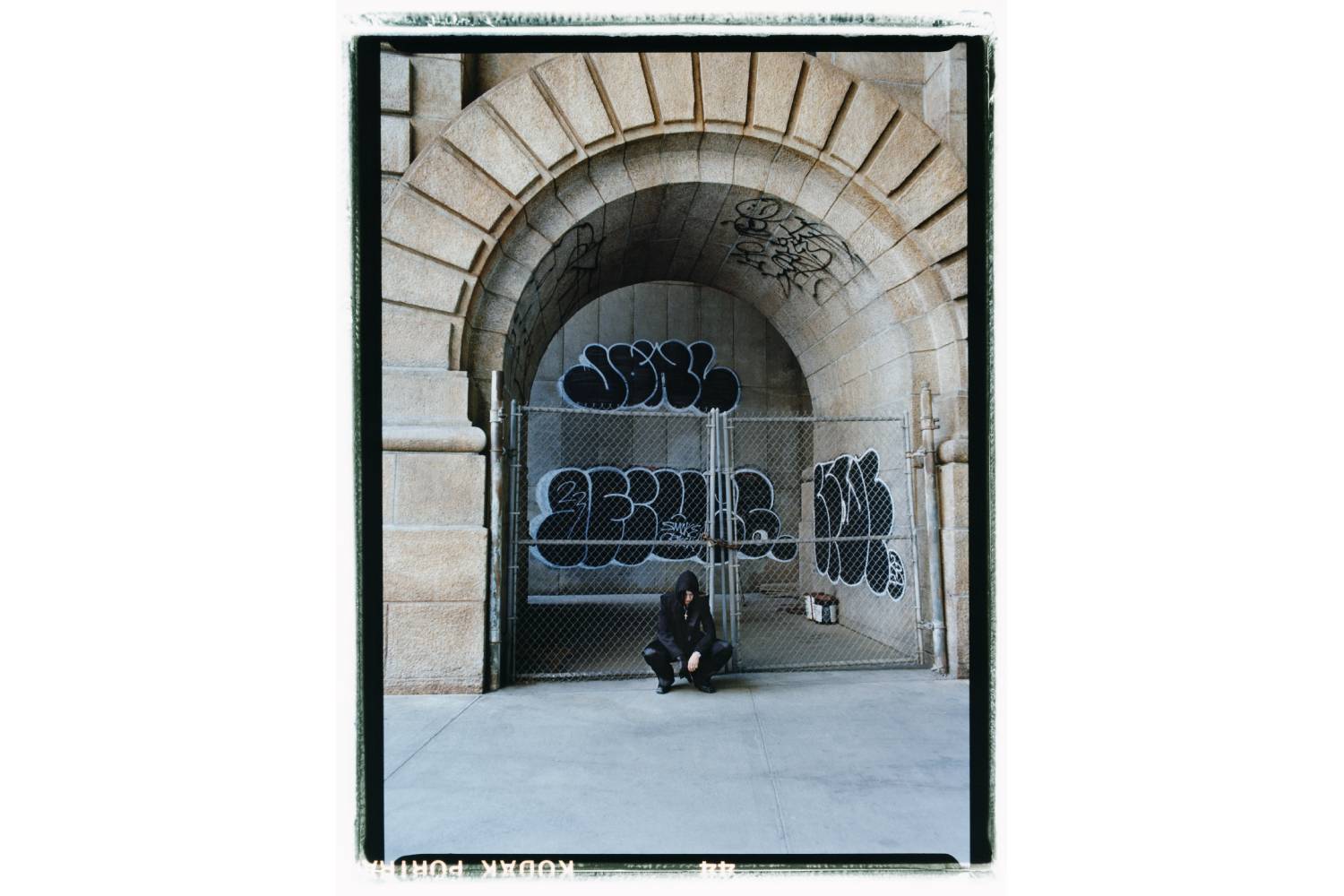

AJ: But when you say “stage,” you don’t mean a physical stage.

AI: Exactly. The stage that is the museum or a street or the studio. My house, or a usual concert stage. In my mind it’s a pretty universal idea.

AJ: A unified focus or attention to something. See, I think that’s a critical distinction to make, because I would say, one of the things I see in your work, particularly in the performances — I feel like we are at least a hundred years past, leading up to the twentieth century, where you have Cézanne, the entrée of African art, cubism, and all these kinds of things, which

ultimately conspire to dismantle vanishing-point perspective. And not just dismantling it as an optical strategy, but dismantling the

psychological, the phenomenological, the philosophical implications of —

AI: Yeah. The order of things.

AJ: That’s what I’m saying. Vanishing-point perspective is more than just a way to organize the appearance of the universe. It’s a tool to order our understanding of the universe. Right? Okay. So, once you get around that, in paintings certain things, other things — crucially — become apparent. Ultimately I feel like a critical aspect of what’s happening in your work is taking the implications of how paintings diagrammatically imposed a worldview, because paintings are ultimately diagrams, and actually moving into this other space

where the erasure of vanishing point or single vanishing point are getting played out. You run different thematics through your form and your aesthetic strategies, but… what I see, what it implies or suggests is, What does it mean to coordinate, to calibrate the attention of the viewer — but minus what? Minus the tunnel, the tube, the lens, the disciplining mechanism, whatever the vanishing-point thing is. What does it mean to direct people’s attention absent that? Which is also connected to blurs and all these other kinds of indeterminate boundaries. This is what we’re talking about. So it’s fascinating to me to walk around inside of your performances, because it’s walking around inside of a kaleidoscope. It’s like, not looking through a kaleidoscope, but being in a kaleidoscope. You know what I mean?

AI: That’s the fun part of putting it together. I try to figure out in advance where the audience will be at a certain moment in the piece and how they move through the space. They change their position constantly and with it changes what they see and how close they are to the stage. I think this is interesting, that the one vantage point — and what you describe happening in paintings, and in the history of representation — it’s very much a given thing.

AJ: It’s overdetermined at this point.

AI: And everything builds up on this. Critique builds up on this.

AJ: Right, totally.

AI: How to look at art builds up on this. What is art? An understanding of cultural landscape. You move in there. I move in there.

AJ: A painting, to me, classically, a painting is a diagram. We can’t lose sight of that. Meaning there’s certain philosophical ideas related to man versus nature. Particularly in Europe ideas like the Sun revolving around the Earth, which we know wasn’t just misguided but neurotic, pathological even. This whole idea of the “I versus the other” being central to how we apprehend the universe, and by implication all that is outside of ourselves, whether it’s a person, a still life, or the heavens. One of the differences between paintings and sculpture, for example, is when an artist constructs a sculpture, they typically understand that it will be viewed from multiple vantage points. Your performances for me operate with this as a given. In the same way, a sculpture is typically a manipulated form without a fixed vantage point. A painting, on the other hand, at a certain point devolved into the sheer dictation of subject, of vantage, of understanding. Your performances seem, to me, to be a step beyond the split between a sculpture and a painting in terms of loosening these overdetermined mechanisms of how you’re supposed to approach the work.When you say, “It’s time.” Yeah, it’s time. Because when I think of… the drummer…

AI: Iggor Cavalera, the drummer of Sepultura.

AJ: Right. Iggor is both an object, a subject, but

he’s also an event. And it’s something about the triangulation of those three things and how he’s positioned, one could say, how he’s composed in the work. He’s a compositional element, but he’s also a catalytic element. And those are two completely different things. It was fascinating to see. A drummer who’s not playing becomes a found object. They become a readymade. As soon as you suspend the functionality of a functional artifact, it becomes pure signifier.It’s like the urinal. What makes the urinal pure signifier is that you can’t piss in it anymore. For a drummer to be sitting there not playing, particularly in the context of a performance piece, it becomes fucking pure signifier, pure POTENTIAL. And so it was fascinating to not just see but to experience your virtuosity, your composition of these points or phenomena or events. Taking these spatial, temporal objects or artifacts, and then not just making Iggor into a thing but making a thing out of Iggor. To see Iggor in a space by himself with nothing

else, not playing, is a thing.

AI: That’s true.

AJ: It’s a thing. And it’s hard to make a thing. Because for us, post-readymade, making a thing doesn’t mean you physically manipulated anything material. It’s like, how you brought together the apprehension of whatever it is that you’ve presented is a different kind of way of bringing into focus a thing minus the guardrails. It doesn’t have guardrails. To me, paintings have guardrails. Like, vanishing-point perspective is a guardrail, and you’re not supposed to go over the rail. You’re supposed to stay as you are positioned. Right?

AI: Yeah.

AJ: So it’s one thing to create an artifact, Iggor in this instance, readymade or not. It’s one thing to create a singular it, but it’s something else to create several singular its, or things, in sequence, in composition. That’s what it felt like to me. Something, for better or worse, fresh. And the thing is… Okay, take hip-hop. When you hear early hip-hop, they’re MCs that are magical. From at least “Rapper’s Delight” or Grandmaster Flash, let’s say. Then, you get to Run-DMC and LL Cool J. And then you get Eric B & Rakim, Tribe, ultimately Tupac, Biggie. If you put those different rappers next to each other, the idea of what was virtuoso changes so radically from one moment to the next, from the early era, every three to four years, versus what folks consider

hip-hop now. People then wouldn’t have even have recognized it as such. They would not consider Lil Uzi, or Young Thug, or Future, maybe even Drake. The MCs now would barely be considered hip-hop to them. It would be like, “I don’t know what the fuck this is.” When I experience your performances it feels a little like that — a little like ape to Homo sapiens. I can see an evolutionary leap in compositional dexterity. It’s funny, with MCs in particular, when you hear them now, they are more casual in terms of how they rap. It’s not hard rhymes, but at the same time, they’re faster, more fluid, more conversational even. It feels like —

AI: It’s also slurring words and —

AJ: Yes. Making the beats more —

AI: Fast, like trap is, which is the blur thing again.

AJ: I mean, the great MCs now don’t even have to rhyme shit. They have the ability to activate associative fields in the absence of rhyme, to create gravitational coherency in completely new ways. When I moved around the performance at Palais de Tokyo, I felt like this is an artist who’s not just doing a rabbit trick; they’re pulling a rabbit out of a hat, then they’re reaching down the throat of the rabbit and pulling out another rabbit.

AI: It’s interesting to me what you said about Iggor and the scene. And for me, there’s Iggor, and then there’s Ruben. And this is fucking with perception. It’s like first you think Iggor is the one who’s giving the beat. But then you realize Ruben and Iggor are dependent on one another. When Ruben is resting, Iggor stops playing, but none of them releases the other out of that loop. But then, when the audience comes, there is another dependency. A trinity. In Paris, I was seeing you standing in the middle of the people in the big room, and there’s this scene, right when Eliza’s up on the one diving board. And then there’s Billy, on the other diving board, and you had this big, particular lens with you. I was thinking, “Wow, this is amazing. He’s doing exactly the opposite. He’s zooming in.” It’s almost a deconstructed image of what it is. It’s also an obstruction to go closer.

AJ: Yeah, for sure. No, absolutely.

AI: Or your choice would be the obstruction.

AJ: Well, the thing about that lens, the Optimo, it was big. It’s a big zoom lens. So it gave me the option of being wide or tight. That’s why, despite the size, it’s worth the inconvenience, especially in a live situation where you can’t stop or repeat actions. And, there’s something about just staying with the same lens. Robert Bresson just used a 50mm lens. All of his stuff is one lens, 50mm. And he didn’t just push that particular lens to its limits but, perhaps more importantly, demonstrated the value or possibility of constraint.

AI: I always loved Pickpocket (1959). And Au hasard Balthazar (1966). Those were two of the movies that inspired me to do my first pieces, especially the ballet of the hands of the thieves. That scene at Gare de Lyon… It is mind-blowing.

AJ: Yeah. When you use the word “composition,” and you said, “my composition.” To compose. See, I think we use that term, a familiar term, because we have a shared understanding of what it means. It means to organize things intentionally. But I feel like now, to a certain degree, it’s a term that obscures as much as it makes apparent, because at the same time that you’ve organized… If you just said, “I’m organizing things.” There’s a lot of things that could mean that don’t necessarily mean it’s been composed.

AI: Yeah.

AJ: And so, what does it mean to control a thing without making it? Without putting your hands on it? That’s the readymade thing: How do you enact a process, enact an artifact, without putting your hands on it? And that’s why, even though I use the term “composition,” if I’m talking just casual, I’ll say, “Yeah, it’s composed.” But in jazz, for example, they create these things that are very organized, very intentional, but are not in a conventional sense “composed.”

AI: I mean, we are at this moment of endlessness that has to do with improvisation. There’s something about it that I think has to do with letting go, on the one hand, but feeling something, on the other hand.

AJ: But it’s both. And that’s why it seems to me, even as we’re struggling to articulate how we operate now, what’s actually at play — we constantly bump into this seeming dichotomy between jazz and classical. It’s a struggle because in some ways you say, “I want it to be out of control, but I also wanna be able to conduct it.” Which would seem to be in opposition to each other, but we know it’s not. We just don’t have appropriate terminology which designates certain aspects of composition without implying all the other fundamentally classical associations — the baggage — as well. One wants the intentionality, the sophistication, the

sensitivity, all the things one might consider the upside of conducting, but without the erasure of accident, the erasure of the aleatoric, the indeterminant.

AI: I really do believe in that — that letting go of control makes the thing more beautiful or perfect in the sense that things come together in a certain moment that would never come together if I, myself, alone, would try to get control. And, I think true collaboration, like I’ve experienced it, it changes you

forever. I’m coming here. I tell you my ideas. We go into this together. I even have ideas only because you are sitting here talking to me. To claim that’s not part of art making and being an artist is crazy to me, but…

AJ: I mean, I think everybody, at this moment, is trying to resist the aspects of these orthodoxies that don’t work for us, but without throwing everything out that’s come before. So, I’d almost say one of the things that’s most forward about your work is your ability to compose with autonomous agents, which would seem, on the surface, to be contradictory. If they’re autonomous, how are you conducting them? How are you controlling them? How are you composing with them? But it’s evident this is possible, to have compositional structure, to create a structured artifact that is open-ended.So, that to me is at the core of, I think, a certain

dissension about what’s happening in your work. And it shouldn’t be, not a hundred years after Duchamp. But it shows us the power of creating things with blurry, fuzzy boundaries. You know what I mean? That refuse to be a certain type of artifact. Art, artifact or not artifact. That’s another thing that’s contentious in your work. Is it art or is it theater? Well, to me, it’s a ridiculous split, but in the context of the art world, where everything is so unapologetically discriminating, it precisely challenges the terms.

AI: Yeah. When I came to see APEX (2013) for the first time at Art Basel Unlimited, this was like a knife. It affects you and it tells you stories. There are ideas like old melodies in it. It’s taking you because you can’t escape it. And then, I don’t like the word usually, but it’s an immersive experience, in the best sense of it: it takes you, embraces you, and then it lets you go and you are free to do whatever, but you’re not the same anymore. All of these things, the being too emotional, too much — all of that could actually be something that becomes a power that I could use in my own way. I can’t concentrate. I see things. I am manic. I’ve come closer to, “Oh, this feels like this could actually be my strength, not my weakness.”

AJ: I call that turning a deficit into an asset. Sometimes I say I wanna create def-assets. I always laugh at this. Seemingly deficits, but, like anything that’s really working… I like to say sometimes there’s a difference between a thing being creative and a thing being procreative. Like punk rock and hip-hop, and jazz too, were procreative. Because, in addition to generating magnificent artifacts — “That’s dope as hell!” — they also make you, even falsely, think, “I can do that too.” You know what I mean? There’s something truly generative, emancipatory even, about a thing that makes you… that empowers you to operate as if you can do it.

AI: And, if you don’t even think you can do it, you at least feel the urgency. The same urgency that made you come back from LA to Paris to see the show again. I felt honored.

AJ: The turnaround. See what I mean? I came back in three — it’s like seventy-two hours. I was like, “Okay. This is a little crazy.” I remember saying to Melinda, “I know this is a little crazy, I just came from Paris, but I feel like I absolutely have to go back.” Even dragging my son along. And he’s bored with most things. Anything I like, he tends to veer away from. But I still remember, not so much art experiences but, you know how you… My parents, they took me to things where I was super bored. Like church. I didn’t want to be in church. But now, I look back on it and I realize some of my most complicatedly rich yet deeply boring experiences happened in the church. And I’m sad I haven’t given my son that at all. I feel like I’ve deprived him of something. The Black church, which I’ve not attended regularly for forty years, is such a fundamental part of who I am. So I brought him to your show in that same spirit. It was like church a little bit. It was like, “Yo, I know you might be disinclined to express that you find this even remotely interesting…” We went to see the Sistine Chapel and he’s there playing Fortnite. You know, you’re sitting there, and everybody’s looking up… and he’s looking down at his console playing Fortnite. I had to just take it out of his hand and say, “Yo, normally I let you enact your little demonstrations of not being impressed, but now I’m going to intervene. I’m not trying to be my dad, but you cannot sit in the Vatican and not look up at the Sistine Chapel.” I was like, “This is nuts.”But for me to fly to LA and then bring him back to Paris with me, it was really like me saying to him, “I don’t know what you’re going to make of this ART. I don’t know if you should make anything of it, but I do know it’s something that I want you to be

able to look back on and say, “I experienced that.” And even when I later shared some of his drawings with you, I feel like that’s all in there. It had that kind of energy to me. So even if he doesn’t say, “I liked it,” or, “I liked the way it tastes,” or, “I like the experience of it,” I know it’s in there because of the kinds of things, increasingly, he wants to talk to me about. Now that he’s away and not in my house, it’s interesting. A person I could barely get two words out of — “What are you doing? What are you interested in?” and just grunting in response — now he’ll call me from New York and say, “Hey, I saw X, Y, and Z,” or, “I saw this and what do you think?” So yeah —

AI: He feels that urgency.

AJ: Yeah. While we were at the Palais, watching your performance, he walked around with me while I was shooting, but he also walked off quite a bit. So he saw different aspects of the performance than I did.

AI: Family is important. I believe in love and the power of it. I lived half of my life with a chosen family. I’m really passionate about it and it is so intertwined with me making work. Things I deal with as subject matters occur in my work as artifacts, they are super familiar to me. I don’t have to go far. I just open my eyes and everything floats right through me. And I just take it and make art. It comes easy to me to know what matters somehow, what I have to look for, because thats what I trained myself in, since I was a child. Looking at things. Seeing things. Ideas are not just born out of us, they have been there forever and belong to everybody. Like old melodies.

AJ: Well, like you’re saying, sometimes people think making a thing that’s good or powerful has to do with making a thing that’s exotic in some kind of way, or it’s got some color you’ve never seen, Vantablack or something. It’s not about that. One of the things that Ifind most fascinating and singular about your work is the combination of the thing being constructed but also simultaneously dismantled in front of the viewer. And in doing this, it fulfills one of my primary metrics of what good work has to do. It’s got to assert something, but at the same time it’s got to question the assertion. It has to cast a spell and disenchant in the same breath.

AI: Taking it away from you.

AJ: It’s got to do both. Like Sleeping Beauty, it’s gotta put you to rest and bring you into a heightened state simultaneously. That just feels to me like the frame of what work should do now.