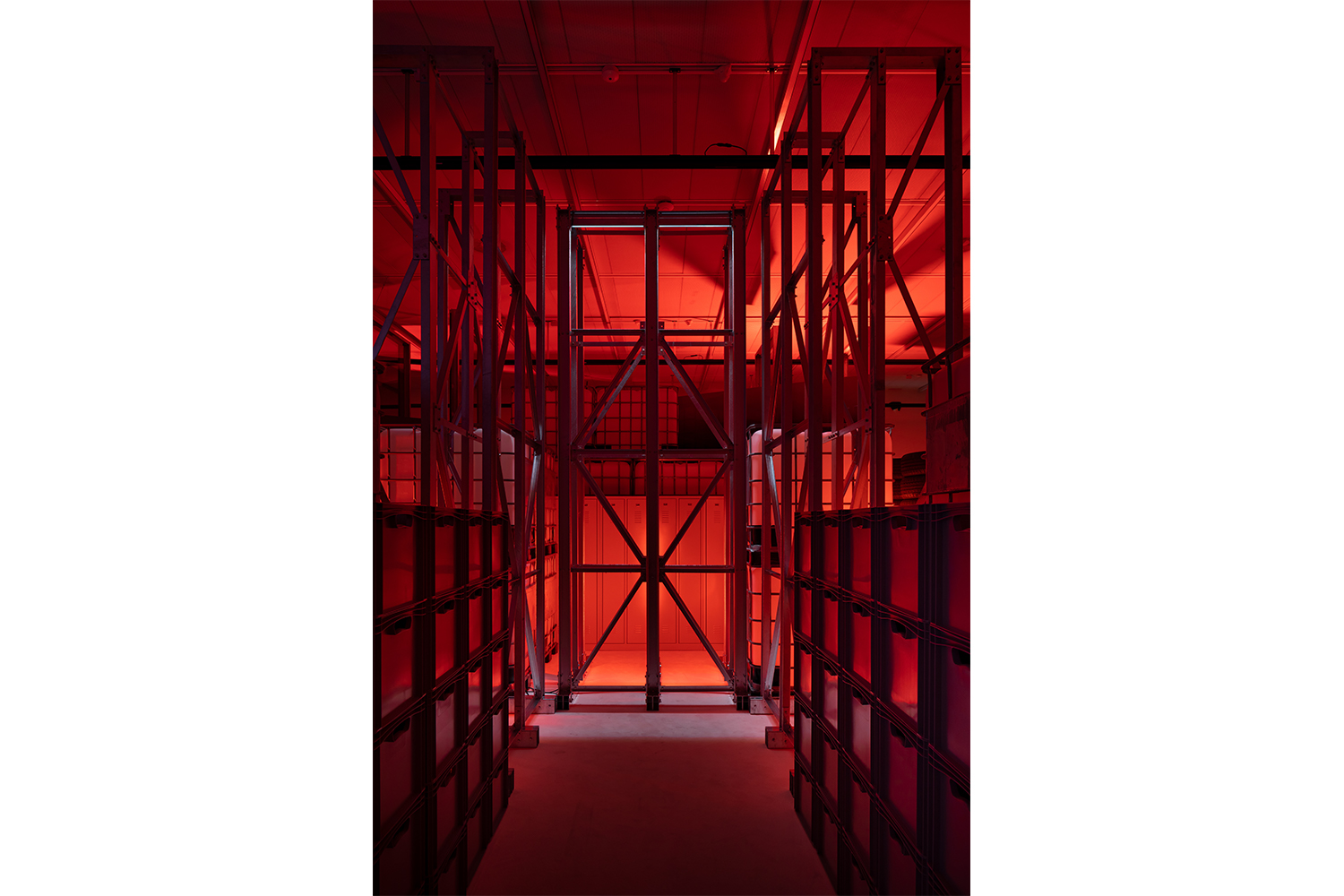

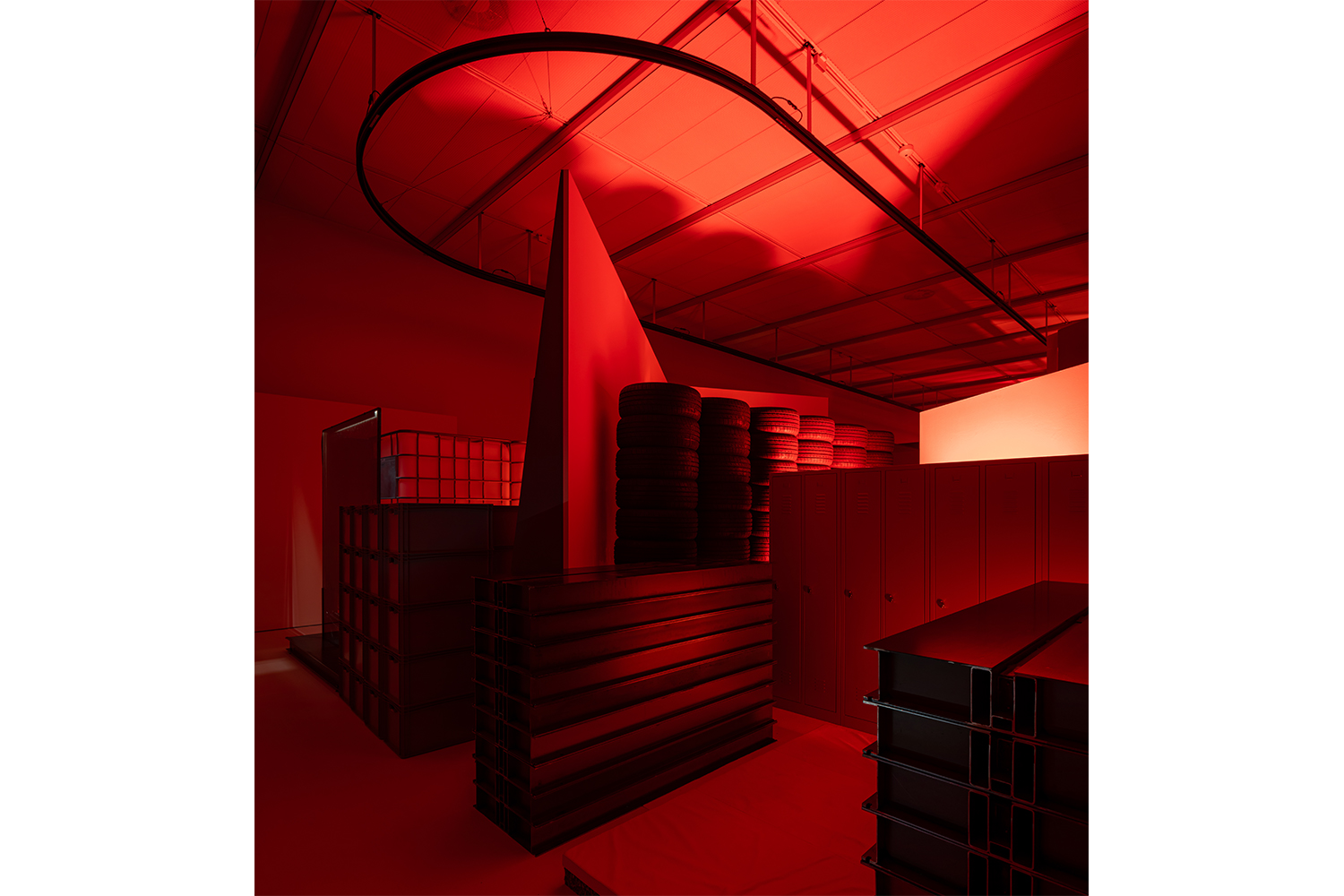

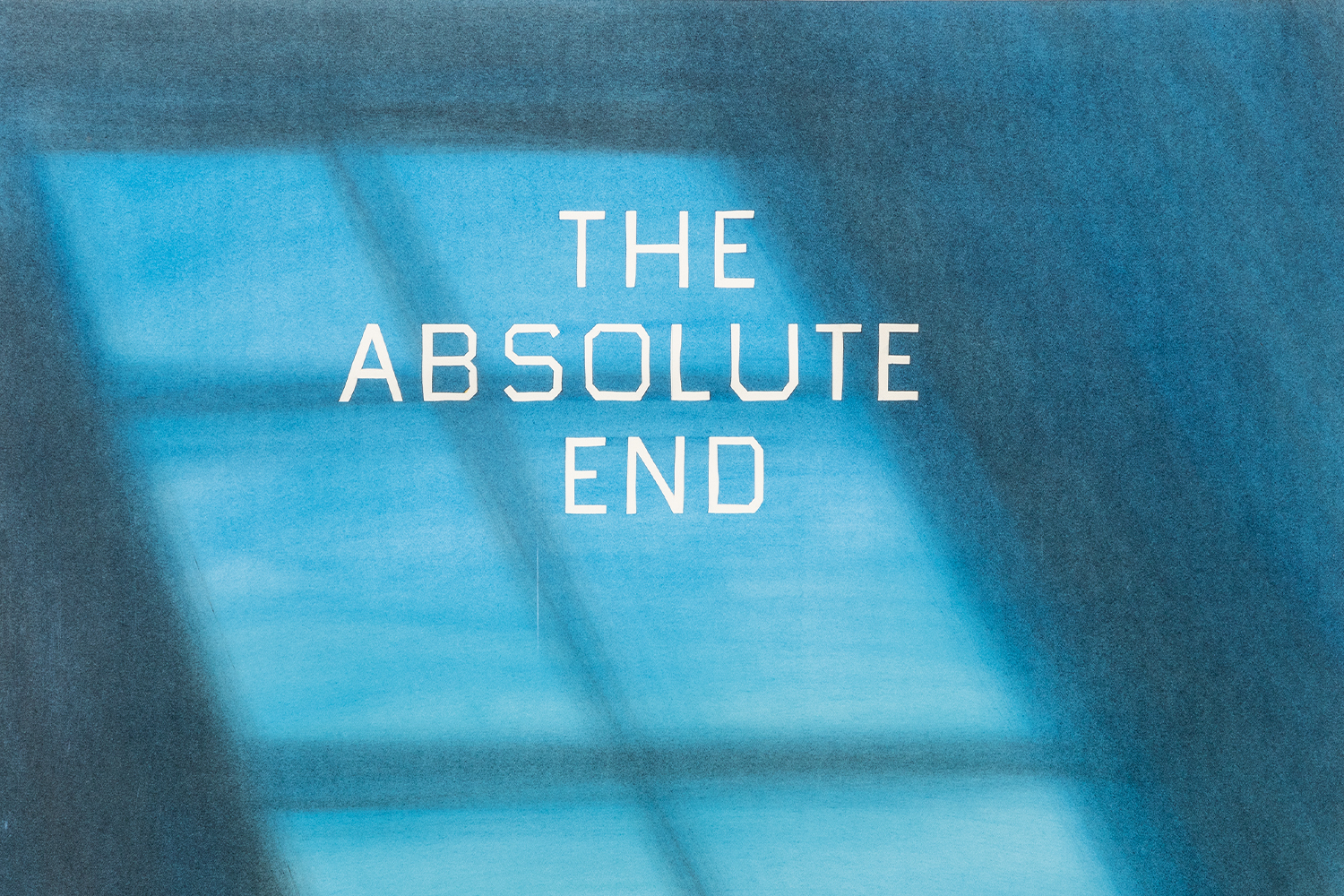

My generation confronts the anxiety of death in a new and peremptory way. I was reflecting on this as I thought about how to frame Anne Imhof’s muscular new project “YOUTH” at the Stedelijk Museum, co-presented by the Hartwig Art Foundation. The first time I saw a performance by Imhof was at Kunsthalle Basel, where she was presenting Angst (2016). At that point she was no longer performing herself, but had a crew of performers, each of them a diamond in the rough. After that, over the years I saw almost all of her projects, including the most crucial ones of her career: Faust (2017), with which she won the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale; Sex (2020–21) at Castello di Rivoli; and Natures Mortes (2021) at Palais de Tokyo. The moment that followed the “end” of each performance left me with a consistent sense of bittersweet estrangement, at times anguish, not unlike having my head in a blender. I thought back to that sense of alienation as I walked through the aseptic corridor of ice-gray lockers that introduces the viewer into the dystopian warehouse setting created in the basement of the Stedelijk. Everything was in there. The smell, the noise, the lifeless objects from every performance seen in previous years. Even though there was real catharsis in this, I can’t deny the fact that I hoped to find some bodies that could shock me. But the body in this exhibition denies itself its own corporeality. The body here exists as a specter among the modularities of the space — another masterful installation by the architecture studio Sub — to remind us that they/we still exist. Thus, I returned to that sense of death that hovers everywhere, in a historical moment in which psychophysical balance is a luxury, and TikTok memes are the mode of representation that people most identify with.

The “deprivation” of bodies in “YOUTH” gives way to the glacial avatar, the object — lockers, water tanks, car tires — or the formality of smoked glass walls, and the disturbing sound, co-produced by Eliza Douglas, Arca, Ufo361, and Imhof, that runs through every square meter of the basement.

In an essay published in Death Clock,1 theorist McKenzie Wark, musing on the death-related anxieties of our time, addresses dysphoria and commodification. In one passage she writes, “Sometimes I think the whole planet has dysphoria. […] The whole planet is running on signals that are making it unhappy, dissociated. Out of whack. And it is going to shorten its life. Or at least shorten the lifeworlds humans need to thrive. […] The unlife of the commodity form is speeding up time. Or rather, a kind of time. It’s speeding up measurable time, clock time. But also: time experienced in relation to death.” Still on the subject of death, I am reminded of a passage from an interview with Imhof in which she recalls the time when she conceived the music for Angst, specifically the song “Dive.” She says, “It goes Dive Dive / My Love / Dive, and when I sang it over the piano it sounded like Die Die / My Love / Die. I liked that.”2

“YOUTH” is also a dissonance. It is a dysfunctional path that welcomes a lonely audience, more confused than ever, who can no longer recognize their place in the world. The two videos in the exhibition return the complementarity of our condition: the human being on one side (impersonated by Eliza Douglas), bewildered and stripped in a snowy landscape, amid the opaque signs of a crumbling civilization and the impossibility of eluding a condition of restriction; and the animal on the other: beautiful brown horses running and quivering gently in the snow, a comfortable condition that for us is far away, inaccessible, possible only through the dimension

of dreams.

The non-life of the commodity — going back to Wark — shortens our life time. We have every reason to believe her. In the same way, we should reflect on her statement that art in general is also dissociated and dysphoric. Anne Imhof’s transmedial installations embody this dysphoria; hers is “an art which is no longer contemporary, as there’s no longer any time to be in time with that which is not a dysphoric signal.”3