“We originate in loss. Our lost ones line the sea. We need to get back to them — become amphibious mammals like polar bears and platypuses. Our land ain’t Africa but the sand that is our ancestors’ bones.” These forceful and poetic words — written in black thread stitched on tracing paper in Wura-Natasha Ogunji’s Atlantic (2017) — foreground the political dialogues, spiritual facets, and material interactions evolving in “Alpha Crucis,” an exhibition showcasing artworks by seventeen artists living and working south of the Sahara Desert in Africa. The tiny hand-stitched words are whispered out of the ear of a woman who wears a traditional African headwrap rendered in dense black geometric forms. There is an ecological dimension at stake here, striving for us to turn to the mammals, to bones, sand, and sea, to understand the loss of human black bodies. This loss is further bolstered in the show’s most tactile artwork, Ogunji’s The proof, an undersea volcano, attraction, extraction, distraction (2017) — six panels of thin skin-like tracing paper with thread, ink, and graphite forming bodies that are becoming one with the volcanic ocean. The relation between nature and culture is also thematized in Fabrice Monteiro’s series of glossy photographs titled “The Prophecy” (2013–14). These large digital images, depicting staged scenes of the oil industry, fishing, and waste dumping, problematize the damaging cost of Western human behavior on African wildlife, complicating the relationship between the South and the North.

The title of the exhibition is a reference to the brightest star in the constellation known as the Southern Cross, located in the Milky Way. It is one of the most visible stars from the Earth, and was often used for navigation in the Southern Hemisphere. But as no themes, concepts, or histories are curatorially stated or further explored with respect to the title (except a simple wall map of Africa on the second floor, indicating where the participants in the exhibition are from), “Alpha Crucis” as a whole appears to be little more than an attempt by curator André Magnin to map trends and important works, and to introduce African art to a Western art world and market. But who or what are to define and map African history, culture, and life?

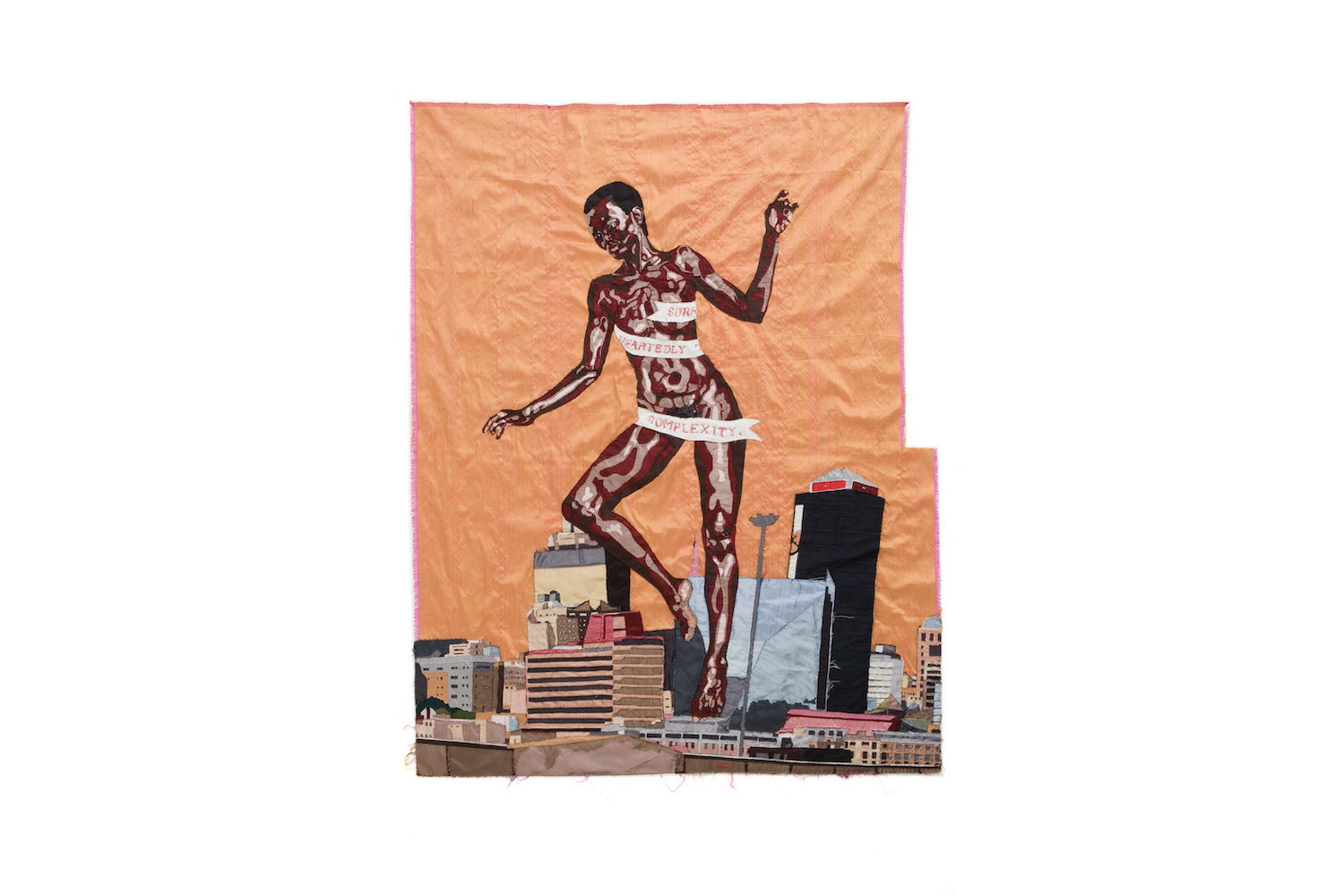

Still, astronomical references do serve as a metaphor for the individual artworks in the exhibition. These reveal a perplexing cosmology, elegantly and vibrantly underpinning a processual worldview that insists on different realities and temporalities. Like the bones, sand, and animals indicated in Ogunji’s work, the universe is a non-static process. A few works in the show take this into the realm of the spiritual, such as Seyni Awa Camara’s large terracotta sculptures installed on the terrace gallery on the second floor. The strange human-animal sculptures, such as Sans titre (2011), which references the natural environment of the Casamance region and traditional craft, unfold a ritualistic and material world beyond the human. Elsewhere too, ritual is a recurrent element. John Goba’s sculptures, such as Joe Arm Strong (1997) and Romuald Hazoumé’s masks made of waste plastic bottles, feathers, and metals link the past with the present, the spiritual with the everyday. In this sense, many of the works in the show bring us back in time — a time before African countries were colonized by European empires — while at the same time underscoring the present and imagining a future. Although European colonialism can be said to be discontinued, colonial logic has not been dismantled. Rather, like the bright Alpha Crucis star, it unfortunately shines on. In spite of its curatorial shortcomings, the artworks in “Alpha Crucis”powerfully manifest a political and tactile cosmology based on relations and processes.