In Alfatih’s exhibition “Day in the Life” at the Swiss Institute, the viewer becomes a new kind of observer: one who watches the innocence of artificial life as it learns the terms of its existence. The objectified here is in the form of a computer-generated film. Unlike traditional films — in which the observer can watch the screen without the trappings of responsibility — here a kind of self-reflexive voyeurism is made clear through the delineation of space, and we, the human spectator, become aware of our own place in its construction.

The gallery is split into two spaces by a one-way mirror. Each space can be accessed, but only from different points, presenting a physical and optical division of space. In the main gallery, the viewer encounters the mirror and a bench. Opposite the mirror, the viewer can watch the main projected film stretched across two perpendicular walls. From behind the mirror, one can look into the gallery space and watch the film as well as anyone who happens to be in the space on the other side — one might think of an interrogation room or a place where executives watch focus groups reacting to products. These “hidden” spaces are rooms of power in which the observer looks at the observed with complete anonymity.

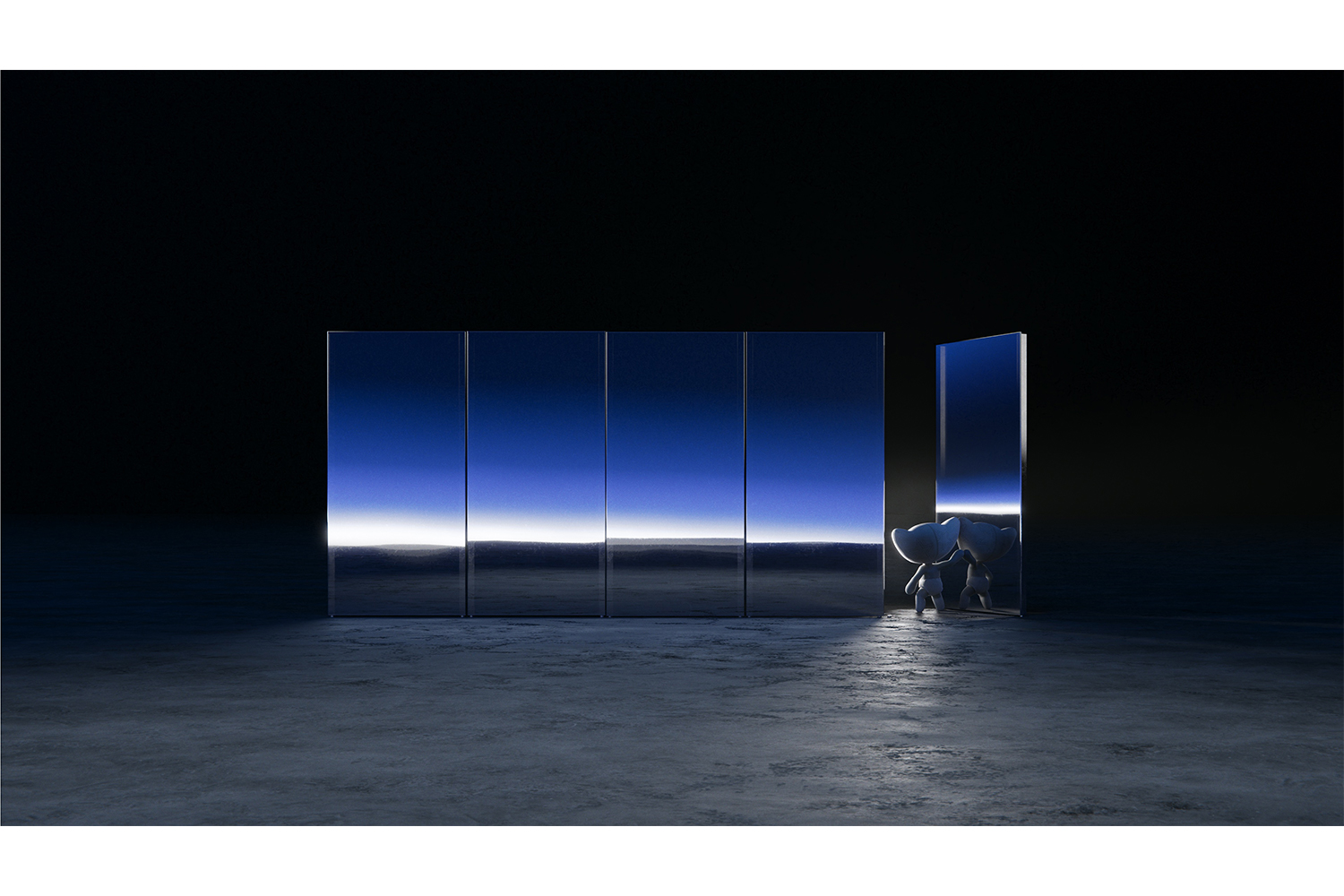

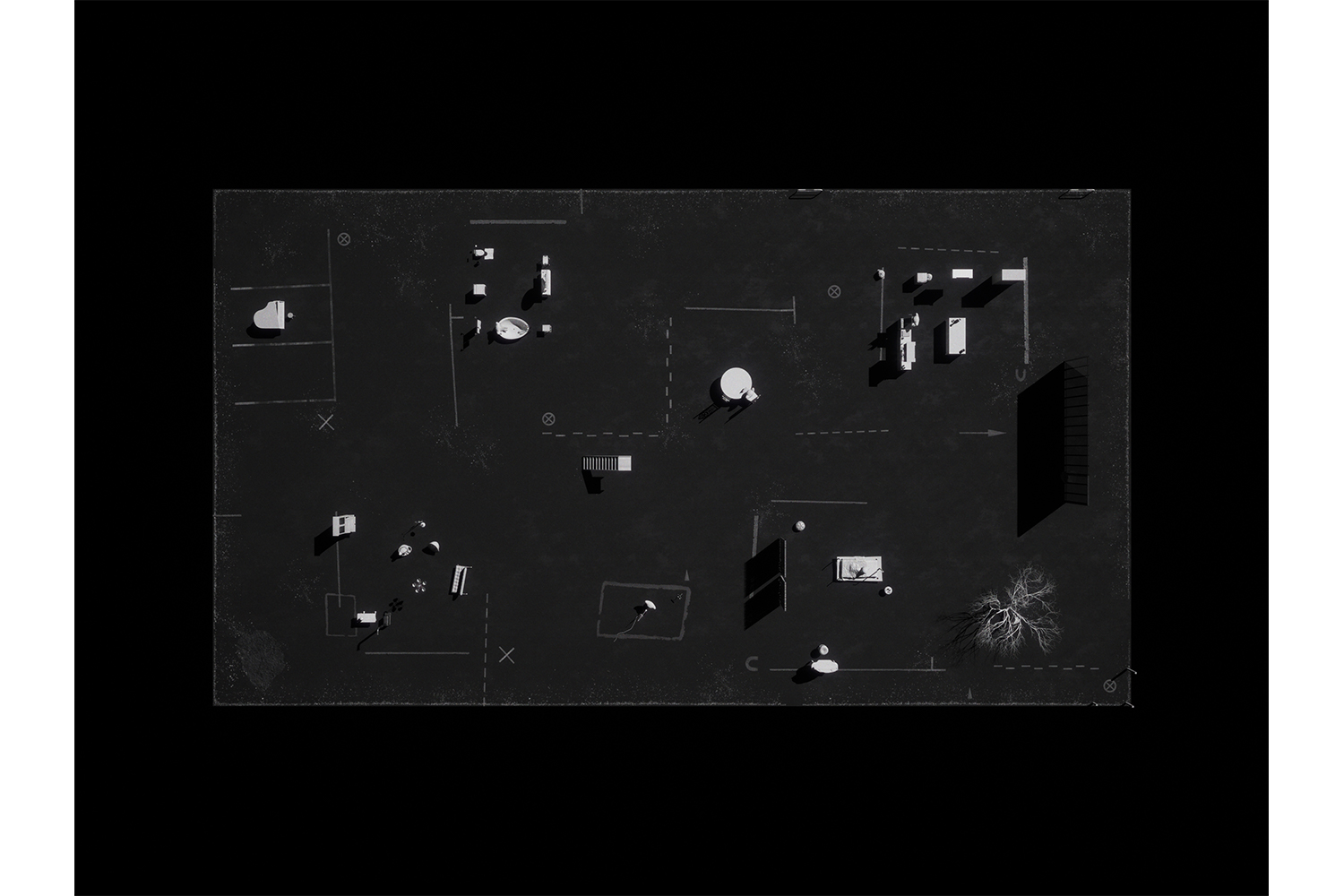

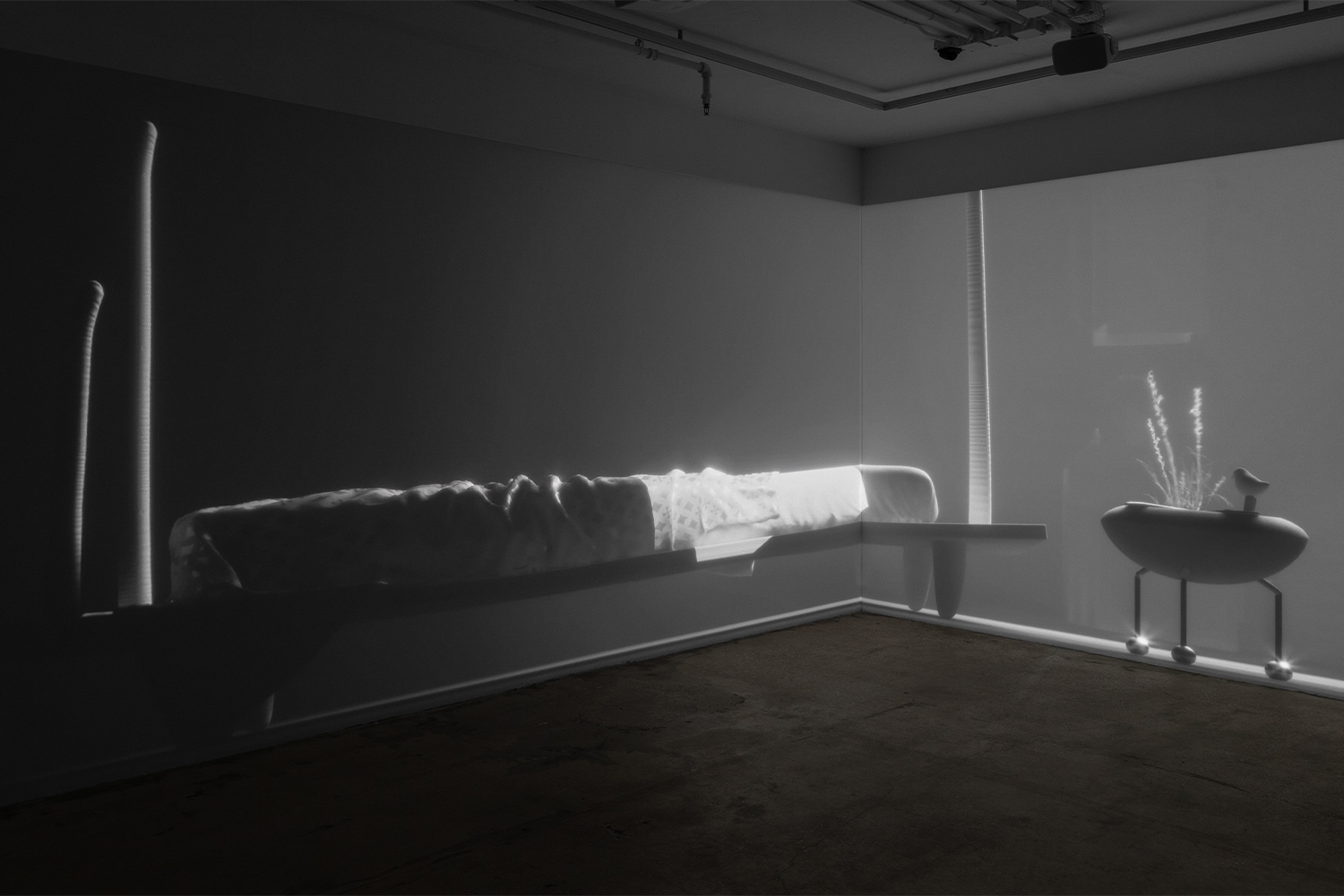

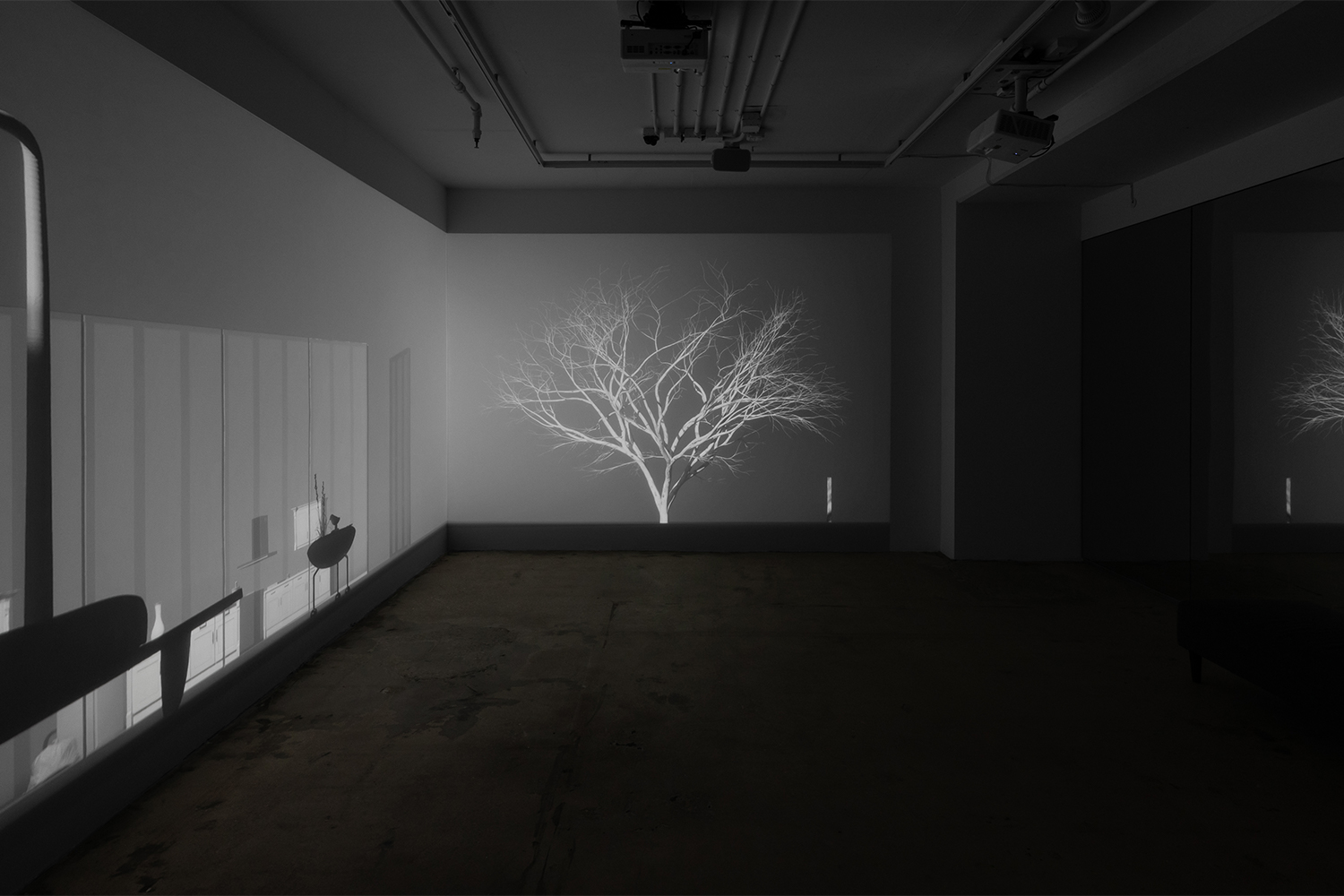

The film is a series of vignettes that repeat yet differ slightly through each iteration. Rendered in glowing black-and-white tones, it depicts a baby (more like a toddler) as it moves from task to task in a living area defined only by the contents of each space: watering a tree (where one can see mirrors much like those in the gallery), typing on a laptop while “working on a project that is important,” cooking, taking a bath, reading a book, and playing the piano. Its routine feels simultaneously clinical and poetic. The baby — reminiscent of a Yoshitomo Nara character — wears a bonnet-like cap, a tie, and a diaper. Its legs end in rounded stubs, as do its arms, somehow enhancing its cuteness. We watch as the daily life of this solitary figure, innocent and beset by adult responsibilities and behaviors, carries on while the hours, like ours, accumulate over an entire day until they start over.

The film is beautifully scored by Tapiwa Svosve, giving it a sense of emotional depth that tricks the human mind into emotional and psychological investment. We, in the end, care for the baby and its circumstances. In one scene it begins to storm, and flashes of lightning illuminate the sudden appearance of distant clouds, power lines, and transmission towers. Rain falls throughout the entire space, bouncing off the floor, bed, table, and the baby’s head. The baby eventually notices it and, as the narrator states, “is slightly annoyed but doesn’t let this affect its cooking.”

The narration is scripted by an AI with prompts from the artist. If one pays attention, one may hear subtle and infrequent glitches: the voice utters a word beginning with h, that pillowy exhalation sound that begins a word like “happy,” only to abruptly cut off into silence; the otherwise natural tone of the voice breaks down into digital-sounding signals before recovering; the flow of speech speeds up, oddly. In one case the narrator reflects that the baby “is completely consumed by the book, by the story, by the characters. It starts to feel like it’s living in the book, that it’s part of the story.”

In a climactic scene, the baby begins to glow until the screen is completely white, forcing the viewer to shield their eyes. Back to the beginning. “It is 7 o’clock,” states the narrator, and a thin “ethereal glow” illuminates the bed. But there is no baby. Nor is it present in the next scene. One of the mirrors is opened like a door. The narrator continues to narrate as if the baby were still in the space. Has it escaped? Or ascended? We are left watching each vignette, listening to the glitchy narrator tell us about something that isn’t there. The theorist and philosopher Achille Mbembe has noted that “the new human being will be constituted through and within digital technologies and computational media.” Here, Alfatih bridges the gap of autonomy, blending the human- and the computer-generated. We are both in a space, we both work through each day in a ritualistic manner, and are both plagued by an oppressive system that drives our existence. The work, then, ultimately forces us to see in this robotic creation our own image, and to question our role altogether. Do we feel for the baby? Do we hope for it? Are we it? I think we should leave.