I relish that no one knows the time one may put into solitude. Yours, mine, alone. One’s interior life is an environment whose information is manifold, teeming, sonorous. Indrawn and brilliant. In this reclusion the world travels with us, eventually deciding on the tendrilous return, fulfilment rediscovered in the refrain “I.” For Simone Weil, the body is the primary filter and orderer of experience, the “I” conceived phenomenologically, mediating action and thought. In this, the “I” operates almost phonemically, upright and somewhat certain, as a border that grasps relations intuitively. If italicized, the “I” slants, emphasizing qualities from a remove and denoting the oblique — to both think and circumvent the self: I. To function, the oblique requires a before and after to read as the flash or fracture it is. If not attachment, then alignment.

K.R.M. Mooney’s work affirms one’s inner world as a dimension of knowing. Courses of knowledge have a stake in the world and thus world-making effects: “Abstractions […] are built in order to be able to break down so that richer and more responsive invention, speculation, and proposing — worlding — can go on.”1 Reactive interiors whose peripheries are dimly embered by tremulous surroundings. I, iridial.

In Mooney’s making, these glistering dimensions unfold to meet physical affinities, alignments and orientations, sensory states, and spatial responsiveness. Calm informants and actants, Mooney’s frequently small sculptures insinuate themselves in space with mild disturbance, extending surfaces and extruding edges, shimmering at a mute yet partly perceptible pitch of agency, like verglas. In their stir of tonal cues, these sculptures are dendrites. Capillary relations, evanescing nerves. The exposure inherent to Mooney’s use of the border or surface is evidently interfacial; cloven by communication, each composite sculpture retains some material integrity while evolving in chemical reaction. This dialogical risk is metered out in Mooney’s deft, tactical coalescence. Each is a reminder that the work’s presumed dormancy or sparseness is but a ruse; behavior simmers indistinctly, tempting observance like sudden glints in a velvety, brumous morning.

In several iterations of Mooney’s recent “Housing” series (2022), rectangular panels of electroplated steel are partially cloistered by folded leaves of copper-infused plastic. Electroplating runs an electric current through steel to seal its surface and ensure cohesion; here, by treating matte silver where steel acts as a base alloy, the technique encourages surface insecurity. Displaying these co-constitutive forces of oxidization, the surface breathes, becomes storied. Stimulating “material disputes” — as Mooney describes them — these activities cite invisible dialogues, which in their unsettled exchange become fitfully articulated. In these textures that touch and chemicals that molder, (im)material relations accumulate at the intersection of object and atmosphere, made visible in the coalition of rust, in the decelerated arabesques of verdigris. Atoms that are not mine but become. Become so: collisions, permutations, lush adjacencies. In the action of ions swapping and calcium mixing with the air, there is something like continuity. Atmosphere, self, and object partake in probing the contingency of form itself.

In these migratory relations, one sees kinship in Karen Barad’s agential realism, whose neologism intra-action (over interaction) challenges individualist metaphysics in a continual process of worlding. Here, meaning and matter do not precede one another. Barad considers the brittlestar as an embodied example of agential realism. An intimate relative to the starfish, the brittlestar has a skeleton with crystals that function as a visual system. Approximately ten thousand domed calcite crystals cover the five limbs and central body of the brittlestar, functioning as micro-lenses. Collecting light, these crystals form the brittlestar’s nervous system. Notably, the brittlestar secretes this crystalline form of calcium carbonate, organizing it to create optical arrays; these arrays appear to form a compound eye responding to diffracted light. Divergent from our understanding of intelligence, we ultimately cannot think like the brittlestar:

“Brittlestars do not have eyes. They are eyes […] its very being is a visualizing apparatus […] For a brittlestar, being and knowing, materiality and intelligibility, substance and form entail one another.”2

Negotiating the brittlestar posits an onto- epistemological offset: “Practices of knowing and being are not isolable; they are mutually implicated. We don’t obtain knowledge by standing outside the world; we know because we are of the world. We are part of the world in its differential becoming.”3 Agency is a distribution, a matter of intra-acting, “not an attribute.”4 Detecting agentic qualities of phenomena requires momentary incisions in which one grasps this oblique once more: together/apart.

The material information and capacities of cuttlebone emulate together/apart attributes. Pulverous yet durable, there is an eldritch resilience to cuttlebone’s ethereal densification; its gossamer strata disintegrated at whim, to mere powder. In Carrier I (2016) cuttlebone is accompanied by millet stalks, steel, and a lavender cast, sequestered in a lacteous glass vessel.5 Exhibited at Kunstverein Braunschweig, the work was attached to a door frame that revealed an otherwise concealed equipment room. This composition and installation of material calibrates space and place as sculptural substance. Tenderly the basin perches. In space it is an almost grammatical instruction; soft directive: a pivot in its pause.6

Returning to the “Housing” works, wafers of silver are inscribed by cuttlebone. Here, cuttlebone’s calcium carbonate complements metalsmithing, leaving a description of fanned reticulation in the silver. In Deposition c. (iv) (2022), charred cuttlebone floats in the center of a rectilinear steel panel. As a metal casting mold, cuttlebone is formalized by Mooney as a biogenic thoroughfare for flows of metal. Mooney mediates the facilities and conductivities of metalsmithing and ornamentation to indicate new capacities, rendering tangential annotations of intra- active alliance. The abstracted conscription of systemic, industrial process is ultimately recuperative: through reoriented care fresh contiguities emerge. They return us to the body as a figure of individuation, harmony, and transgression. In this flexure, the germ or contaminate is a vivifying agent. See in Second Affordance II (2017), wire filament curves into a narrow metal tray of water, meeting the corpuscular form of cast lavender. Contrastively fragrant and formed, the technic-lavender deliquesces in souring oxidization.

The conduits and skills related to the field of ornamentation — molding, casting, soldering, engraving — diverge from the social domain in which such coded presentations of adornment are most visible. The actions and facilities rather become extracted and deranged by Mooney to open out objects as severely entangled entities. This tactic also adheres to the revisions and morphologies of site and space. Forms of enclosure are continually denatured by the work’s installation, which might latch on to interstitial volumes or thresholds of a given architecture, dwelling across ceilings or upon floors. In these transversal inscriptions, the immured consolidation of space is temporarily loosened.

At times, the objects are themselves bracketed and braced assemblies of form. Engraving blocks, for instance, become polished capsules, caesurae rooted to the ground. Each orb is ultimately an incubator for material involvements that are laid bare: nuggets of oxidized silver indenting the atramental jell of bitumen (En iv, 2022), unclaimed rings of cast mistletoe, fulgent-frozen (En I, 2018). In these titles, too, is a kind of fastening: the series’ numerical index follows the prefix “en,” which might weld itself to other words, gemlike, and prefigure a kind of occlusion/inclusion: envelop, enclose, engage. See also Mooney’s jewelers’ vices fixed to columns or beside balustrades: inlaid with a tablet of delft sand, impressed by a serif emblem of silver (Detrition (i), 2019), or crowned with cast mistletoe (Eutectic c. (i), 2020). In these works, Mooney collapses inventories of material that are predicated on an object’s capacity to hold, carry, and expose its constituent elements with careful, frugal display. Cradled, twixt, clinched.

Using a threshold as a site of attachment, Citation (2021) recasts the base objectivity and intermediary operation of a brass kickplate by reorienting the object to a vertical position, protruding from the surface to which it is attached. Patinated and oxidized over time, the kickplate has accreted contact, absorbing the consequences of transitional movements. Being between, its zone is contact, and its contact is subject to an inherently spatial dynamic. In these adjourned temporalities, Mooney’s acute perception of architectural details and environmental conditions share in queer phenomenological readings of space. As Sara Ahmed writes, “A queer phenomenology might involve an orientation toward what slips, which allows what slips to pass through […] a queer phenomenology would function as a disorientation device […] allowing the oblique to open up another angle on the world.”7 Where Mooney’s composed proximities persuade the expression of secreted intimacies, where they induce an act of “facing” that challenges how place and subject cohere, they are surely kin to a “disorientation device.”

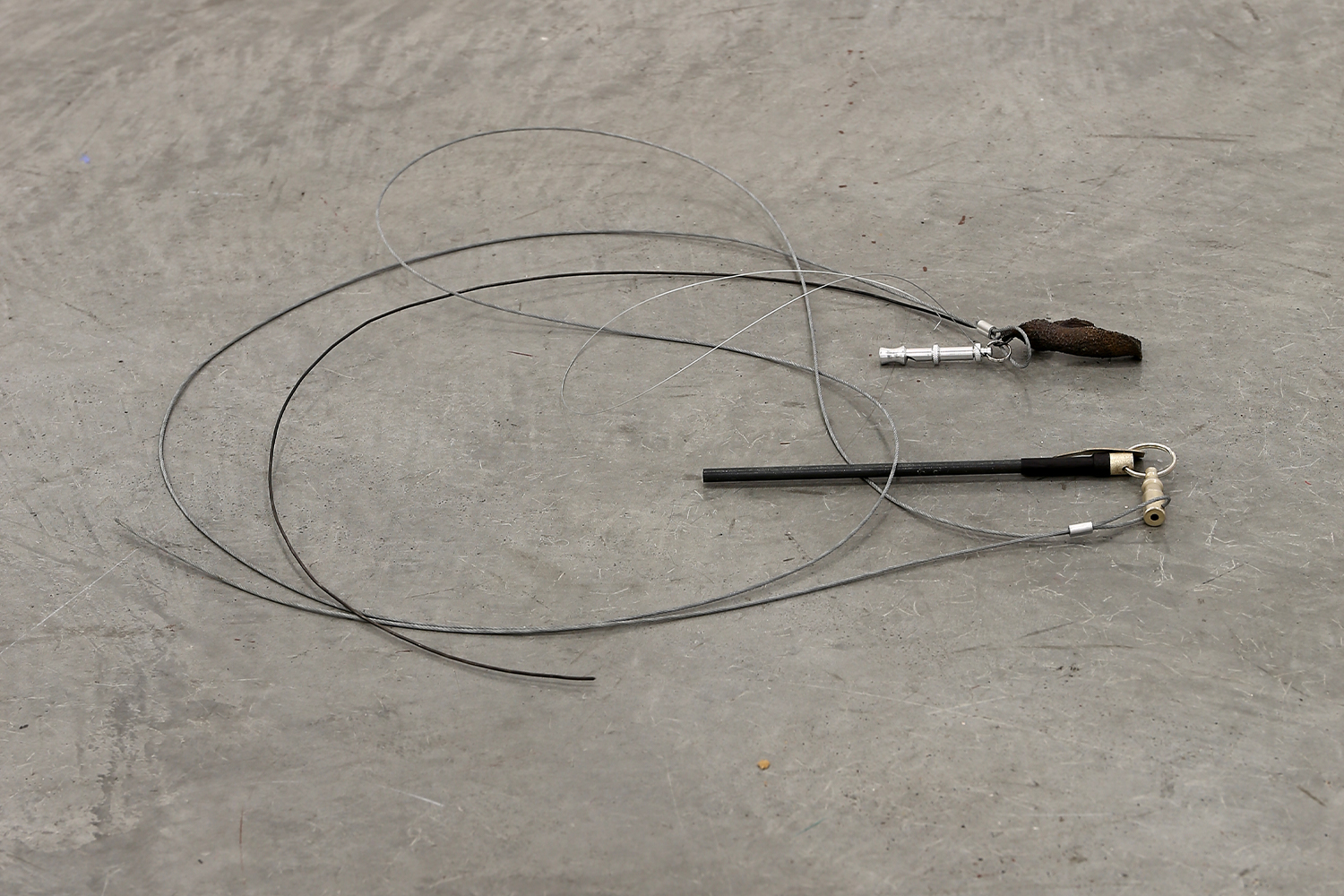

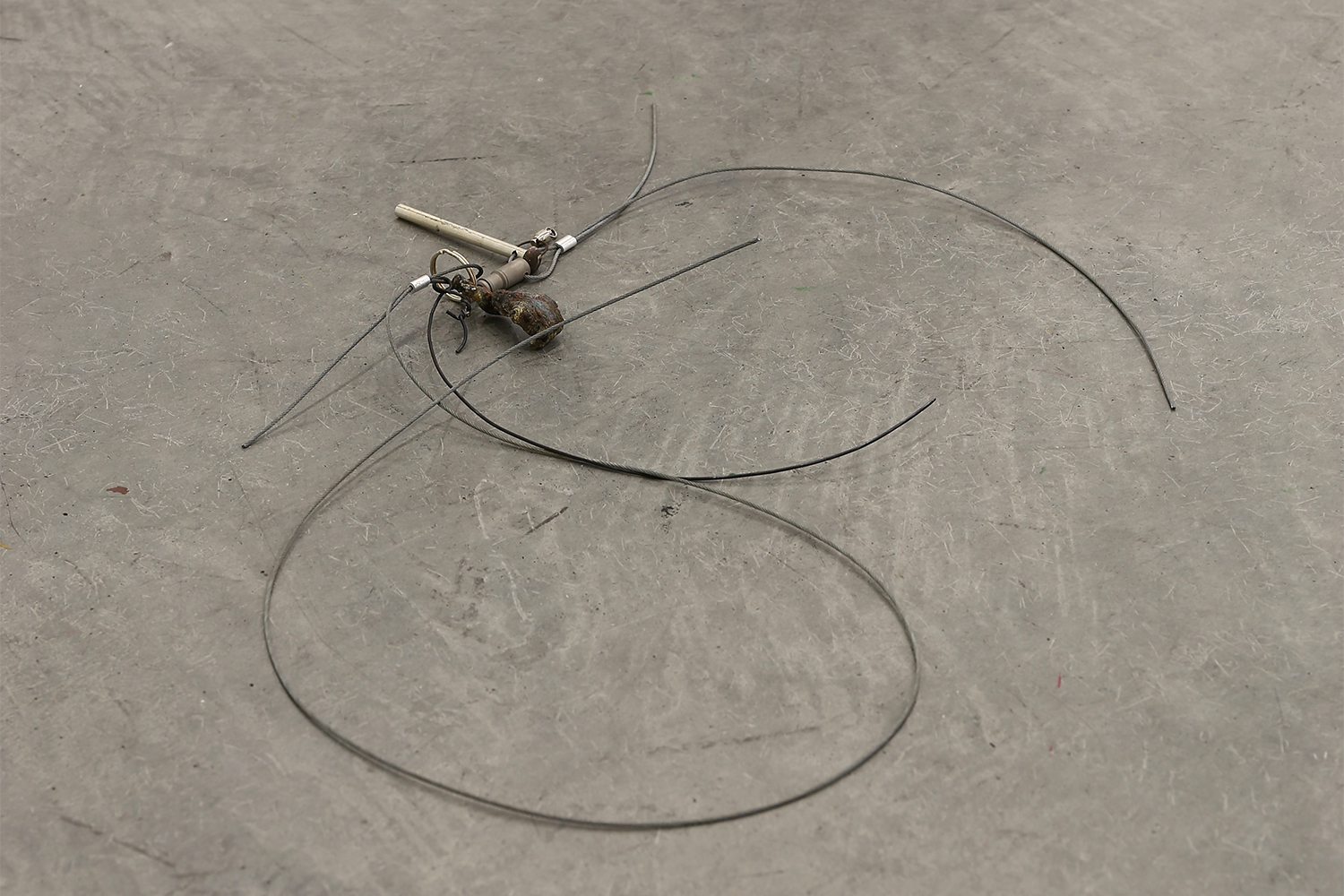

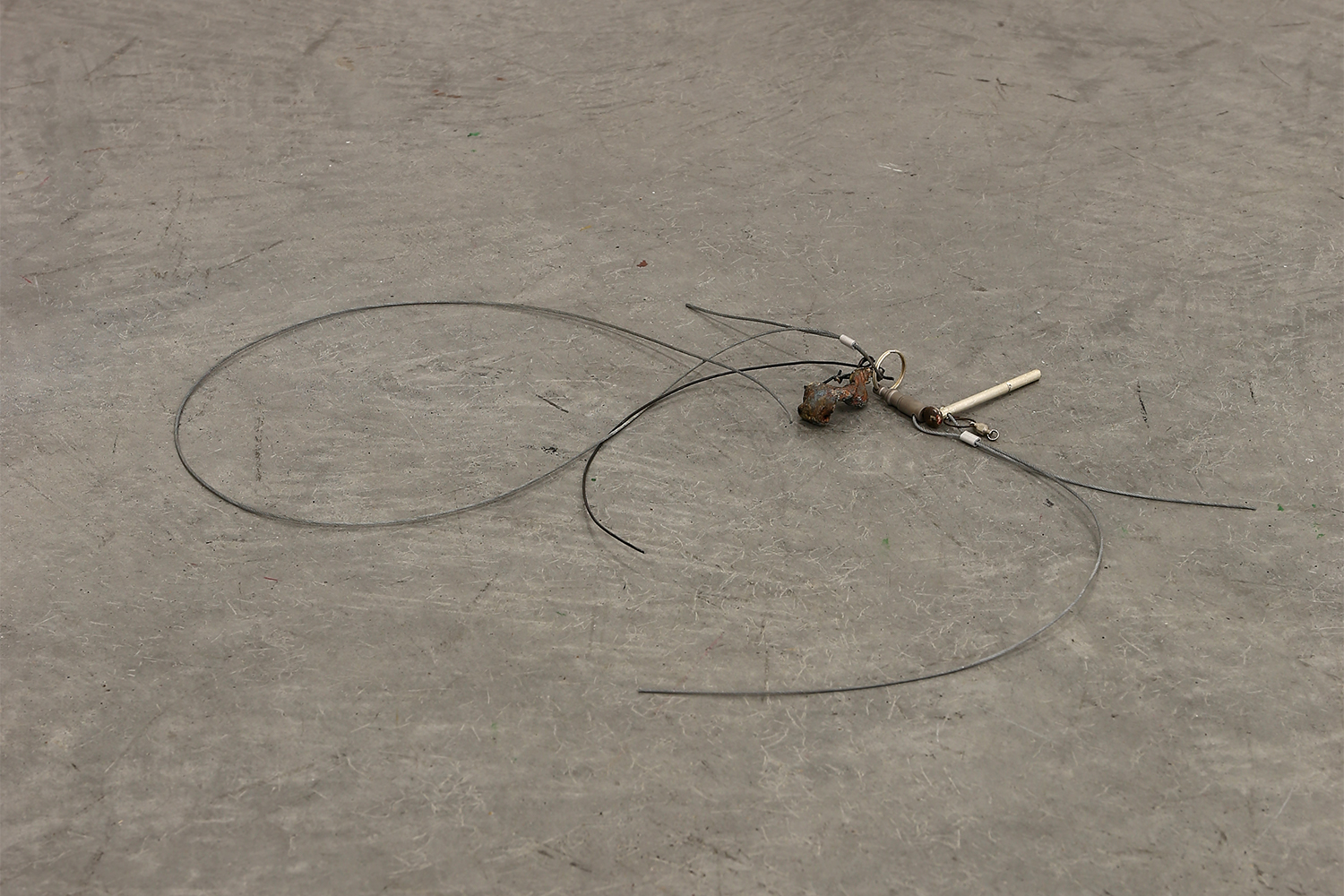

These relational and embodied apprehensions of space are broadened by Mooney’s application of horizontality. The horizontal sets a lure for engagement that nourishes closeness: Awnings are recast on the floor beside a pneumatic actuator that converts compressed air into mechanical motion (Second Affordance I, 2017); gracile arcs of steel cables and binding wires intersect silver-plated keychains (Circadian Tackle and Circadian Tackle II, 2015); semitransparent polycarbonate sheets are stretched on slightly arched aluminum frames, echoing skylights above (Accretion I, 2018). Cut across these dilations and distillations and one can recount the speculative field of the horizon as the locus of potentiality. Affirmed by the work of José Esteban Muñoz, the “warm illumination of a horizon”8 inaugurates a reparative view of the future whereby to think queerness is to think prospectively. By claiming queerness as a type of becoming, Muñoz implies queerness develops a structuring concept where “the future is a spatial and temporal destination.”9

In this behavioral, post-minimal language, Mooney’s orchestration of indwelling potential is perhaps most plenteous in the invisible motilities of sound and airflow. “A priority for me is to attend to an object’s ability to act as a political agent,” says Mooney, “to have a voice and participate in public life.”10 Silver-plated dog whistles, titles after songbirds, castings of mouthpieces of woodwind instruments, clarinet parts, or components of bells — these relate to space and bioacoustics, the physical emittance of sound and its spatial resounding, emotive conveyance, behavioral signaling. In the rematerializing of sound’s apparatus — canals, cavities, chambers — its excess of presence as an object makes that which is absent more present. The ability to make sound and to be heard is transposed to contingent material properties and industrial processes, with consequences expressed across the surface and within the hollow.

For his 2016 exhibition “Oscine” at Reserve Ames, Los Angeles, Mooney installed a window to replace a former wooden one. The window is an object in itself as well as an envelope, framework, or portal for its surroundings, a sealant or barrier, a mediator or mirror. It is an impossibly accurate prism for Mooney’s praxis — the inevitable and irreducible relation of self, space, and place. The window’s content is a shifting murmuration of life, the filtering of light, the reflection of oneself laced in surroundings ahead and behind. Its content is a subjective experience of a series of presents. The rhythm of lasting(s).