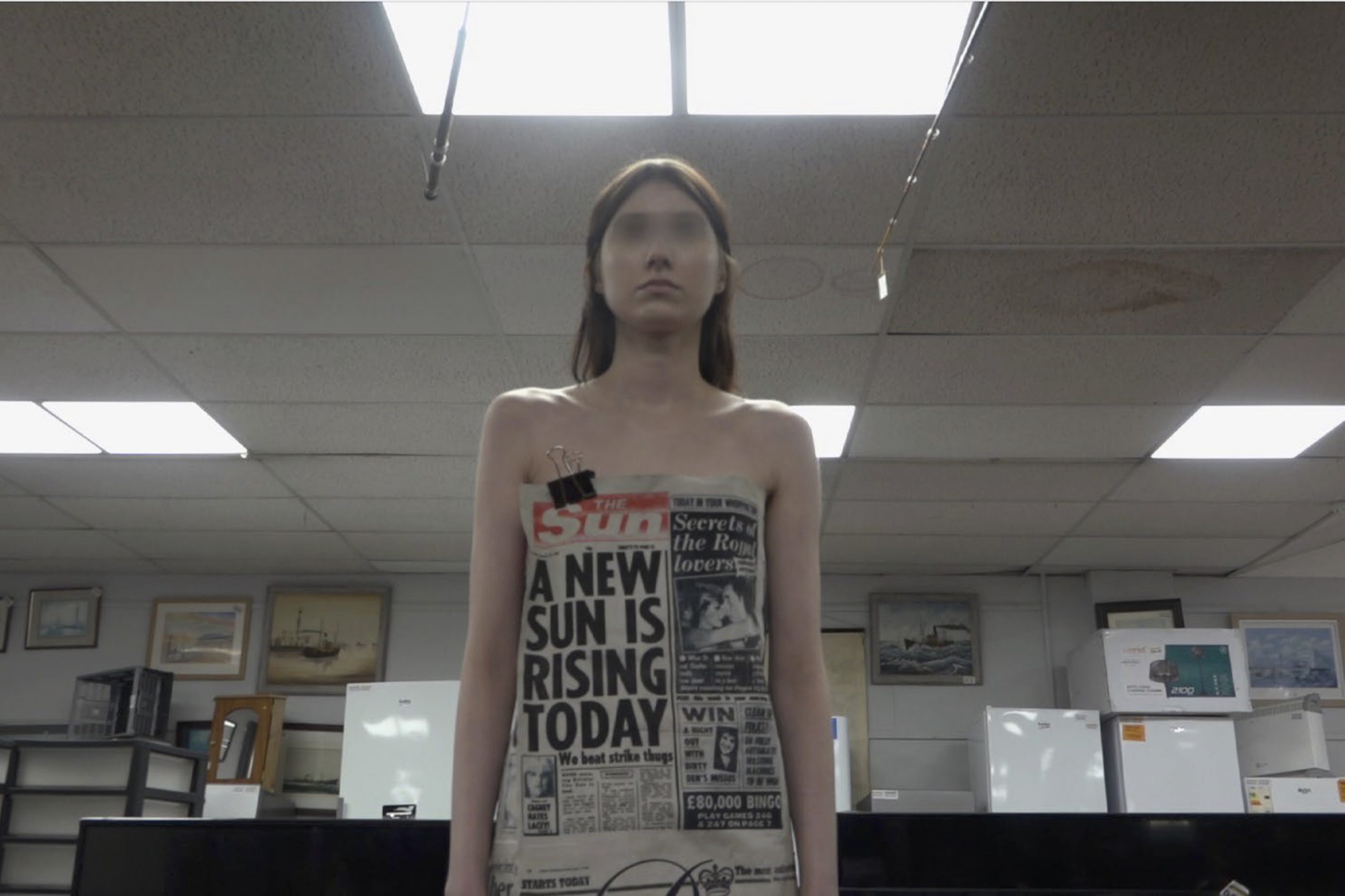

Auto Italia’s street-facing window displays facsimile posters for Les Misérables. On them, a text addendum reads: “Tonight’s performance has been CANCELLED due to unforeseen circumstances.” This recalls October 4, 2023, when Just Stop Oil activists took to the stage during “Do You Hear the People Sing?” (According to Wikipedia, the anthem is “a revolutionary call for people to overcome adversity.”). The action was one of many protests across European cultural sites and institutions. The logic: interrupt the appreciation of “autonomous” artworks, turning attention to the context we (artworks included) are living through; that is, climate catastrophe. Therefore, the show can’t go on.

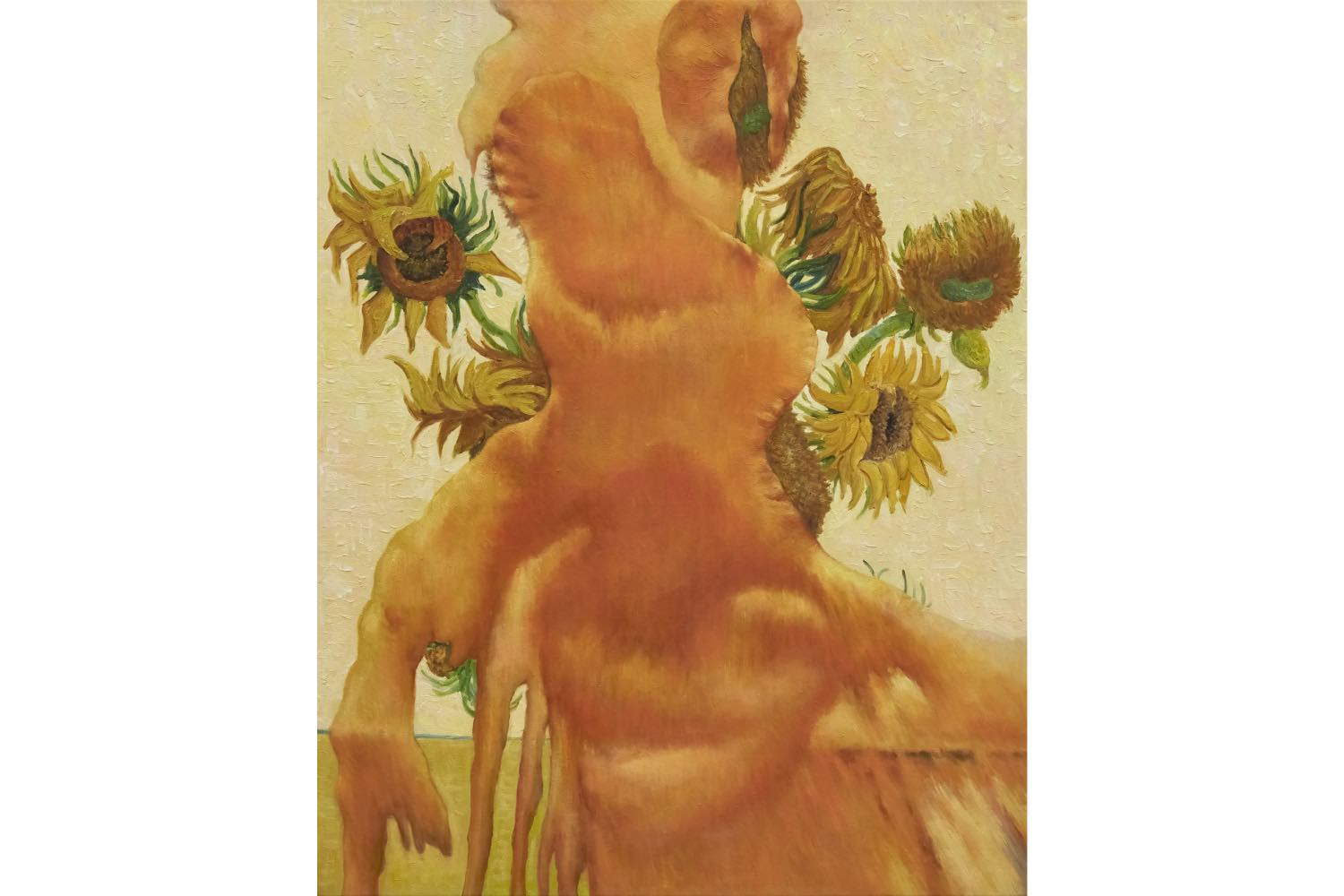

Inside Alex Margo Arden’s “Safety Curtain,” an impossible assembly of works by Western art-historical icons — Velazquez, Van Gogh, Monet, Leonardo — have also been embroiled in acts of protest. In Arden’s oil reproductions, material traces of protest have not been diligently erased by conservators. Instead, impact holes and soup stains are painted into their very fabric: impasto, sfumato, tomato.

Arden’s paintings may seem anti-conservation — exposing rather than hiding interventions — but they share the conservator’s forensic understanding of an artwork’s evolution over time. Conservators retrace steps, sifting through a work’s many material and socio-political states to mime the artist’s physical and mental gestures. Do the job well and no one realizes the interventions are there, like a bewitched audience that forgets an actor is acting until the curtain call. But if paintings change, what moment in time do conservators choose to recover? A museological discourse that values historical tradition, linear development, authenticity, and source, privileges an “original” condition, a now-lost unity. But not always; the same museums that erase interventions by climate activists and suffragettes simultaneously display historic religious iconoclasm.

Arden lays bare multiple narratives upon the picture plane advancing discontinuity and rupturing aura. A triptych of Mona Lisas takes this further, selecting moments when cream cake was applied to, smeared across, and then wiped off its protective glass. In each canvas, both foodstuff and portrait mutate. The evidence is unreliable — pieced from unofficial images circulating online – but titles cast the works as official crime-scene documentation, e.g., Scene [14 October, 2022; National Gallery, London] (2024). We are not asked to assess damage or revisit questions around the ethics of protest. The work does, however, implicate institutions — their politics of visibility and value — in how both artworks and actions are received and read.

The gallery’s back room continues unpicking museological stagecraft. A photograph of a safety curtain — a protective barrier first installed in 1794 at the Theatre Royal on Drury Lane — also performs a symbolic function separating stage and audience, art and life. (Fittingly, this eighteenth-century invention came as museums were establishing their own protocols of encounter.) John Napier’s barricade set design for Les Misérables is reproduced on a backcloth and photographed in three London theaters: a three-dimensional and contingent set rendered two-dimensional and mechanically reproducible. Filling the room’s center are crates recovered from the Royal Academy Schools (where Arden studies) are presented. In these are scenes not unlike Napier’s barricade: detritus from museum storage — ladders, brooms, frames, as well as condition reports and cleaning utensils — all stacked up. But, unlike Napier’s, the props are accompanied by identification numbers, as in a gallery vitrine. The resolutely frontal display speaks to both scenographic and museographic conventions. On the crate’s sides, stickers detail previous contents – “Cast of a bearded centaur,” “Head of Castor colossal plaster cast” –, referencing 1960s student protests when plaster casts around the UK were damaged as symbols of arcane conservative curricula(they did not represent life as it was being experienced). On the tension between the politics of art and life, Douglas Crimp’s On the Museum’s Ruins (1993) notes how, in the nineteenth century, Karl Friedrich Schinkel banished casts from the Altes Museum, favoring marble and bronze. Crimp cites this as definitive of “when the art museum became a place not for study in the furtherance of creating new art but the veneration of masterpieces.” For very different motivations, plaster casts were also relegated to storage.

Retrieving and repurposing items from museum storage and spotlighting backroom “campaigns” through processes of reconstruction, “Safety Curtain” interrogates what institutions choose to conceal. In exposing such cover-ups, the fourth wall is broken, restoring vital connections between art and life, including the artwork’s own life. A picture is no substitute for anything; it is, however, a thing that functions within a networked world, one that has just exceeded a global average temperature of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.