Perrotin Gallery’s Alain Jacquet (1939–2008) retrospective is a pop-colored historical overview clustered tightly around some sixty two-dimensional works. The exhibition suggests a critical re-reading of Jacquet’s oeuvre through its title, which refers to the artist’s very first pictorial series, “Jeu de Jacquet” (Backgammon Game, 1961), which relies on a punning reference to his own name. That early series gave rise to the basic rules of his oeuvre, which thus appear like a set of complex variations around wordplay, systems of chromatic logic based on the separation and permutation of the colors of the game of backgammon, the camouflaging of initial figures, and referential and serial systems of logic. This re-reading bestirs an analysis of this body of work that goes beyond its affiliation with the Pop art movement, of which it is a component part, and urges us to find therein a subtle interplay of Duchamp-like references.

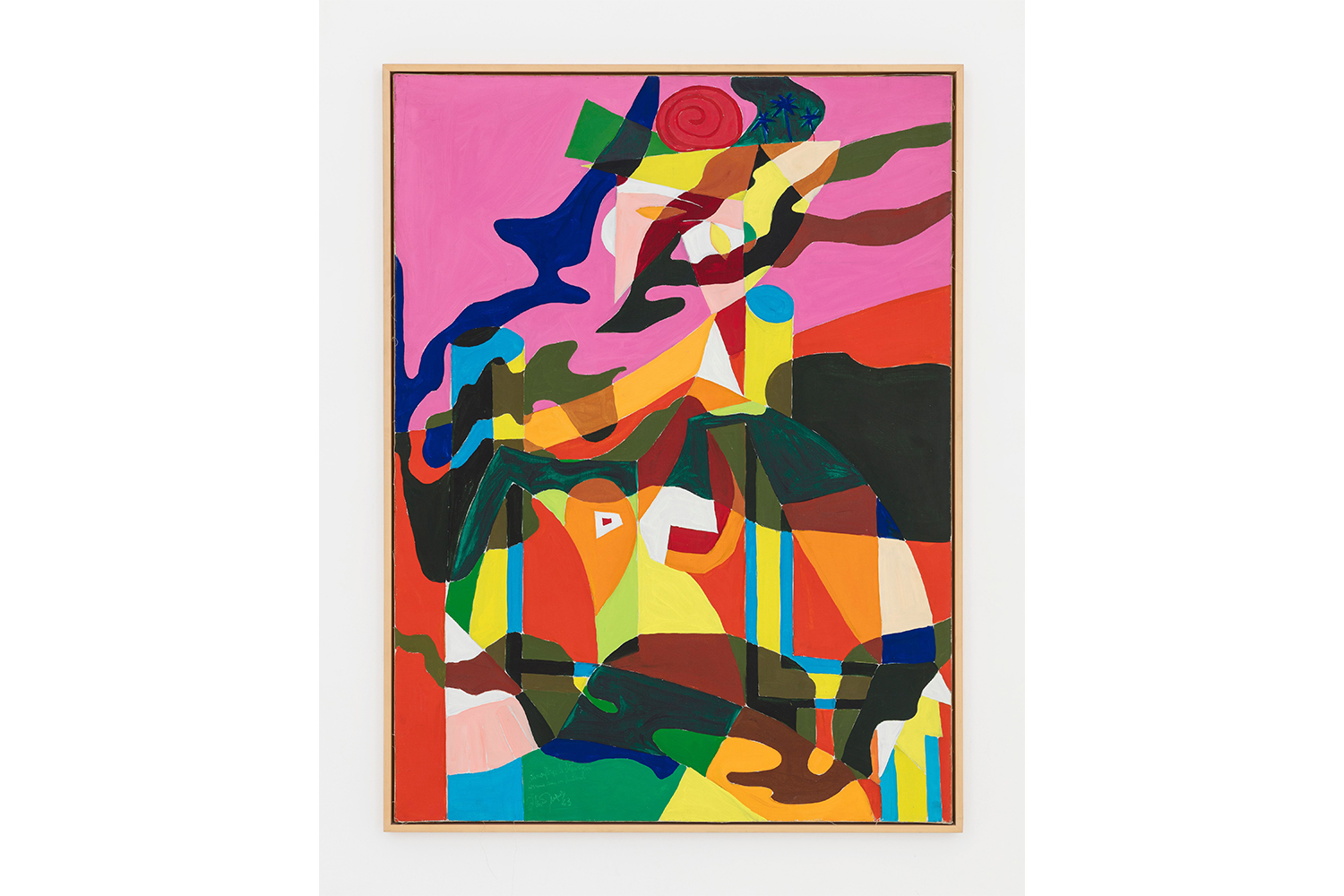

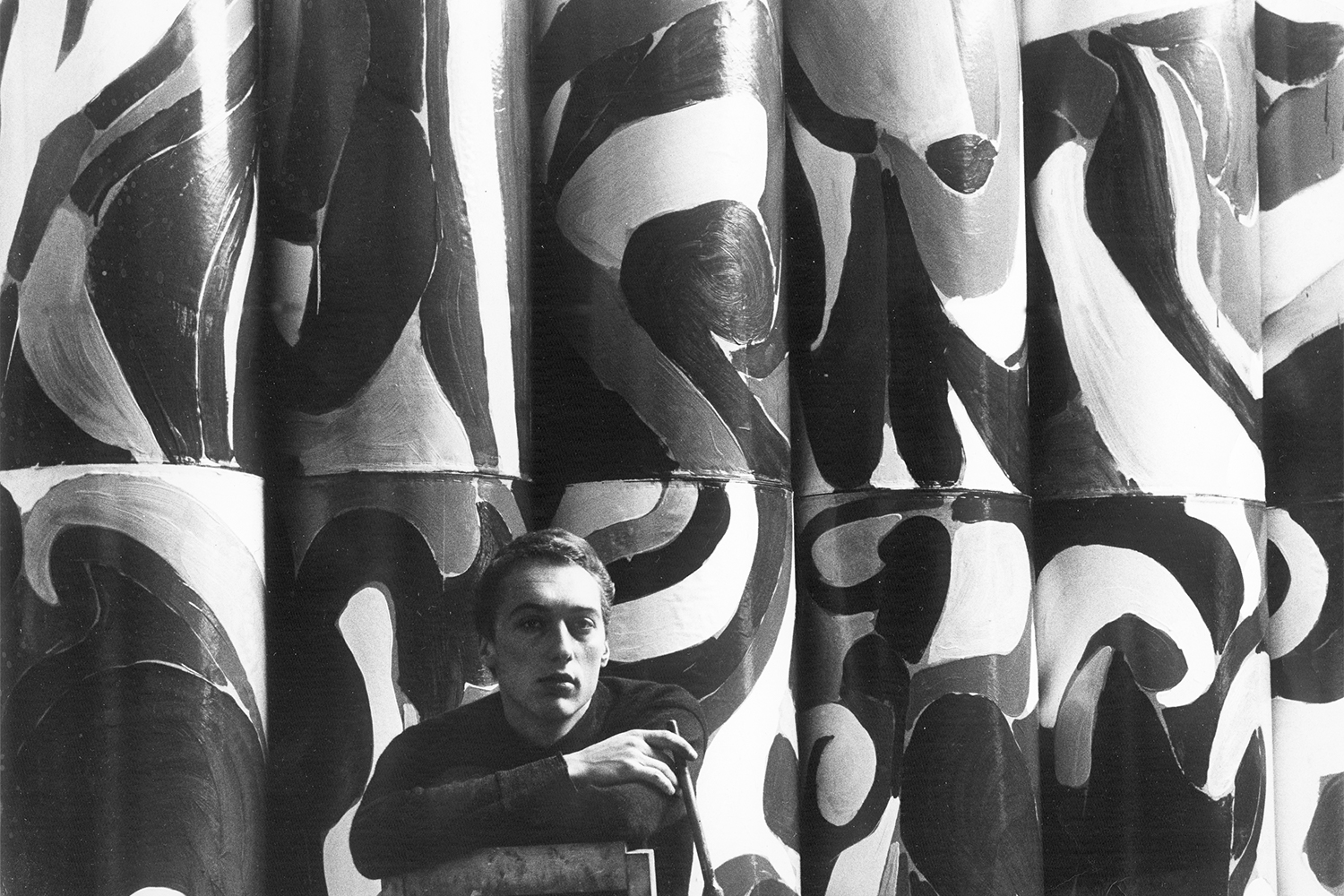

Sans titre (Untitled, 1962) is part of an early set of oils on canvas, akin, from a formal viewpoint, to the “jazzy motifs” (John Ashbery) of Jacquet’s Mur de Cylindres (Wall of Cylinders, 1961), with which he initially made a name for himself. The former works are variously related to or part of the series “Images d’Épinal” (1961–62), which took as its referent assorted eponymous prints of French popular culture, which are also associated with the idea of cliché. Those large-format canvases with their backgammon colors, which include L’Union entre la France et l’Autriche (1962), create a camouflage of these images, broken down into elementary geometric forms drawn freehand and augmented by subtle interlacing. But Sans titre, on view for the first time, might conjure up a work by Marcel Duchamp, perhaps The King and Queen Surrounded by Swift Nudes (1912), representing a possible transition to the series “Camouflages” (1962–64), shown at the Iolas Gallery in New York in 1964. Based on the principle of overlaying two iconic works, as in Camouflage Lichtenstein/Picasso, Femme dans un fauteuil (1963), or an iconic work and an advertising motif, such as Camouflage Statue de la Liberté (1964), this series, whose superpositions create forms akin to the American military canvas, may be seen as a critique of the recycling of artworks in various advertising media such as postcards and posters, and in this sense conjures up Duchamp’s iconoclastic gestures that enhance reproductions of the Mona Lisa.

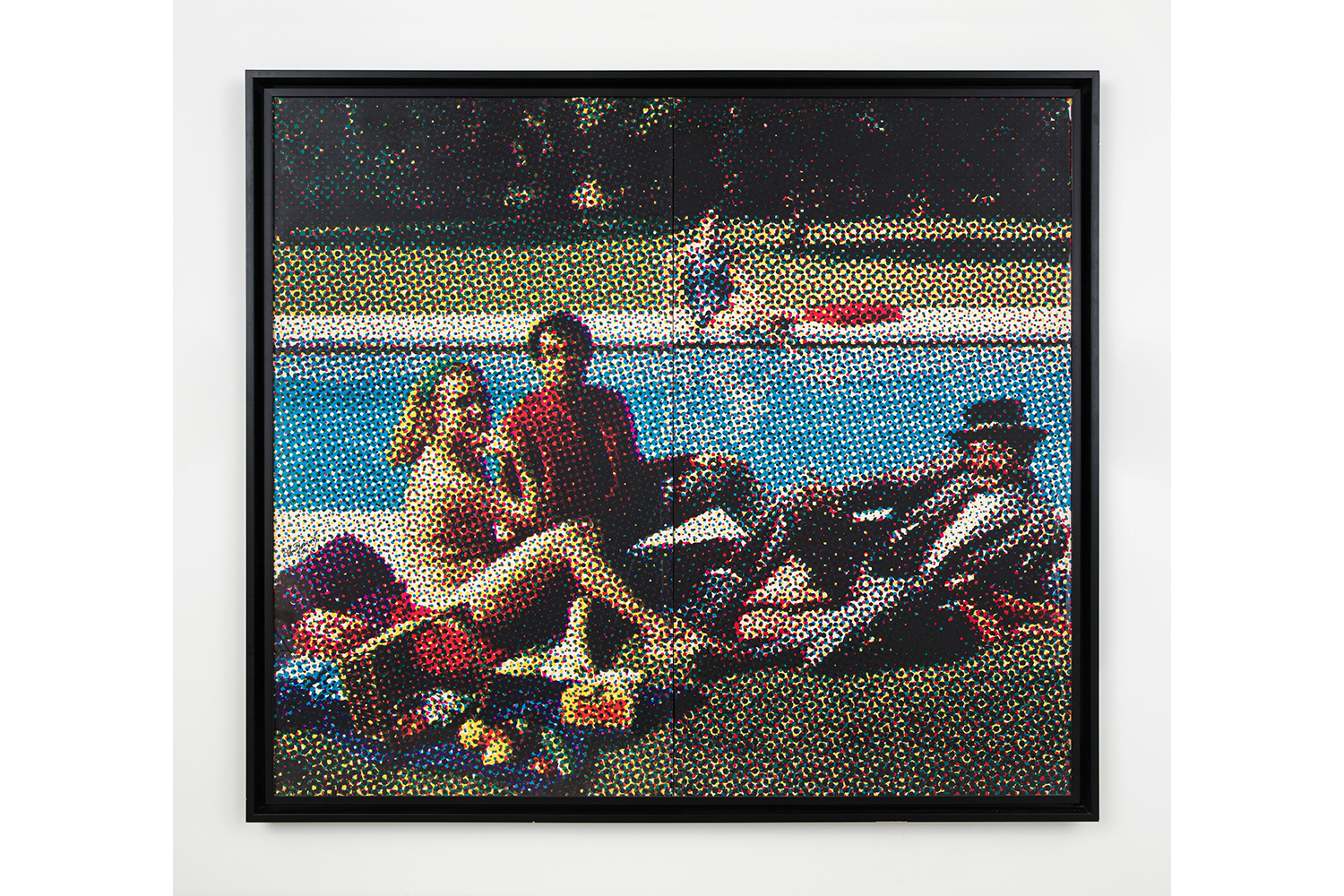

This critical praxis probably lies, like these rules of play, at the root of the invention in 1964 of a “mechanical art,” based on the intentional enlargement of the grid of photographic images as a hijacking of the silkscreen procedure — consisting of the separation and superposition of dots of primary colors — which is the basis of American advertising posters, including their reproducibility. This “Mec’Art,” which does away with the artist’s hand, creates an interplay or game with the onlooker, who is able to distinguish the image hidden in the grid only by moving away from it. Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe (1964), a photographic transposition of Manet’s painting of the same title, represents its first — and most famous — iteration, and includes numerous hidden references. A set of figurative enlargements using differing scales of dots issue from it: Portrait d’Homme (1964), Portrait de Jeannine (1965 and 1966), and Limite entre le béton et l’eau (1965) engage the viewer in a sumptuous and jubilant game, one that resides in these differences of scale enhanced by an interplay with the medium.

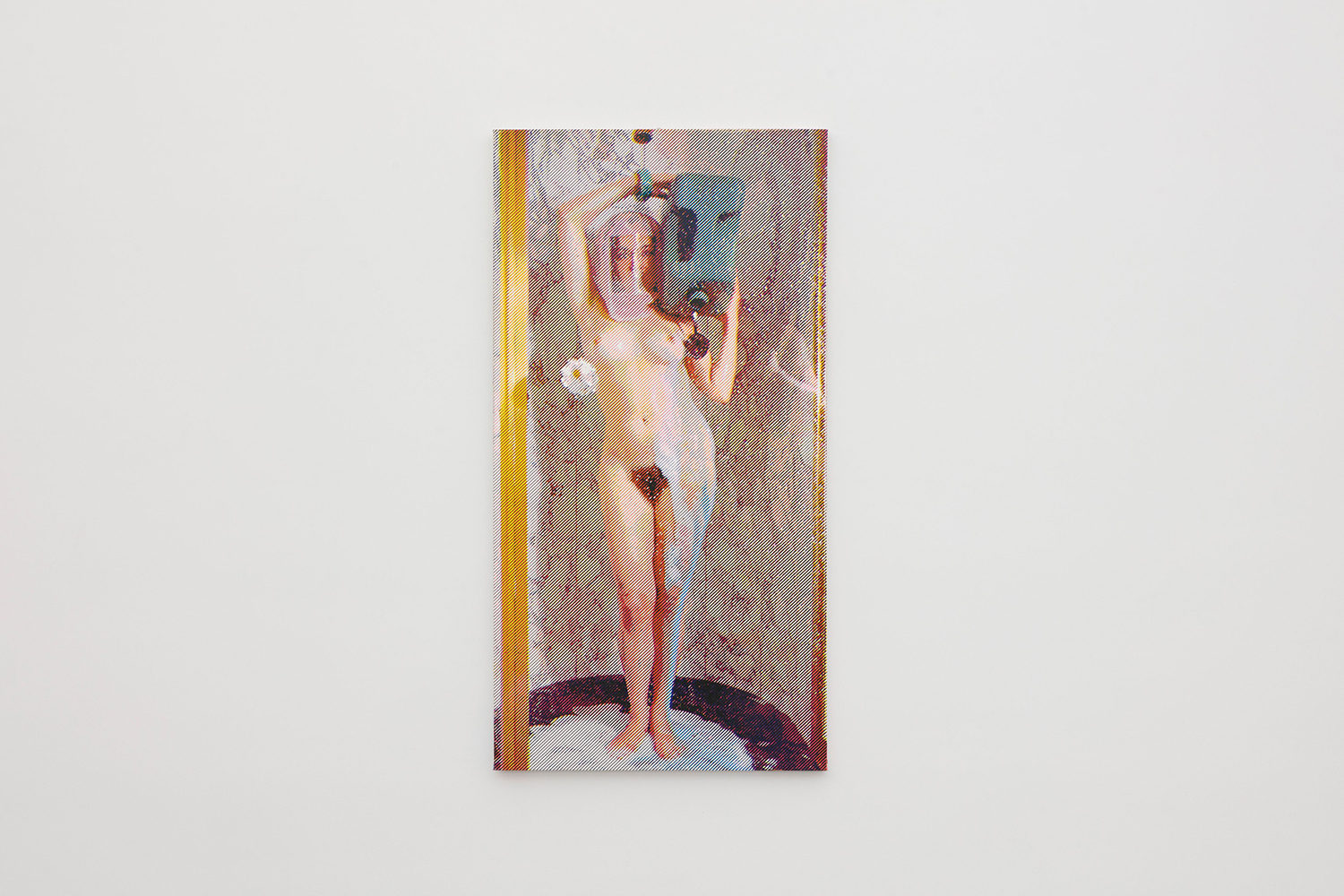

From 1965 onward, this game was carried out via the linear deformation of the grid. The series resulting from La Source (1965), a remake of Ingres printed on vinyl, is one of the first occurrences of this, and DS Boys (1965–2004), an enlarged detail of a photograph with the same title, hails from wordplay on “Mec’Art.”

The vast derivative set of The First Breakfast (1972–78), a silkscreen print repainted with oil, of a photograph of the earth taken at reveille, first thing in the morning, by astronauts on an Apollo mission, presents a concentric grid that Jacquet maintained through his latest works. The final series of “computer paintings” evokes, like Donut avec amas d’étoiles (1990) and La Danse (1995), a Duchamp-like connection through the motif of the Milky Way, and a final wordplay.