It’s hard to circumscribe a figure like Akeem Smith: fashion designer, stylist, visual artist. From an early age he absorbed the roots of Jamaican fashion from the house of Ouch, his grandmother Mama Ouch’s atelier that designed looks for dancehall parties in Kingston. As a teenager, Smith began to approach the world of avant-garde art and culture in New York, working at Tokion and on projects with Telfar, Andre Walker, and Shayne Oliver — making a notable contribution, alongside the latter, to the styling and casting of Hood By Air. Section 8, a label he founded in 2016, makes deconstruction a stylistic hallmark of the brand, yet makes no secret of its political streak — the federally funded “Housing Choice Voucher Program,” also known as “Section 8,” is a government program that helps low-income families, the elderly, and the disabled afford decent, safe, and sanitary housing in the private market.

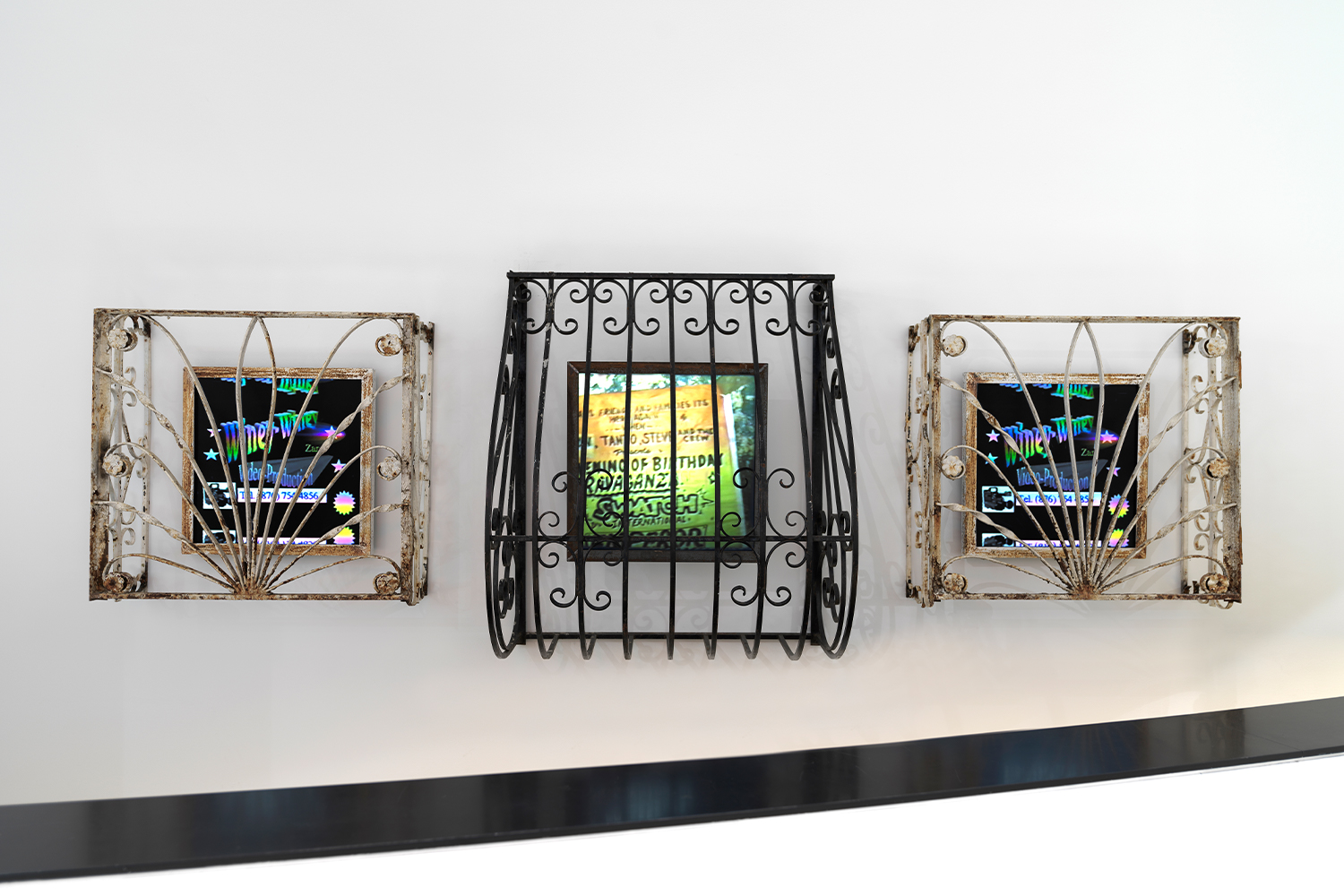

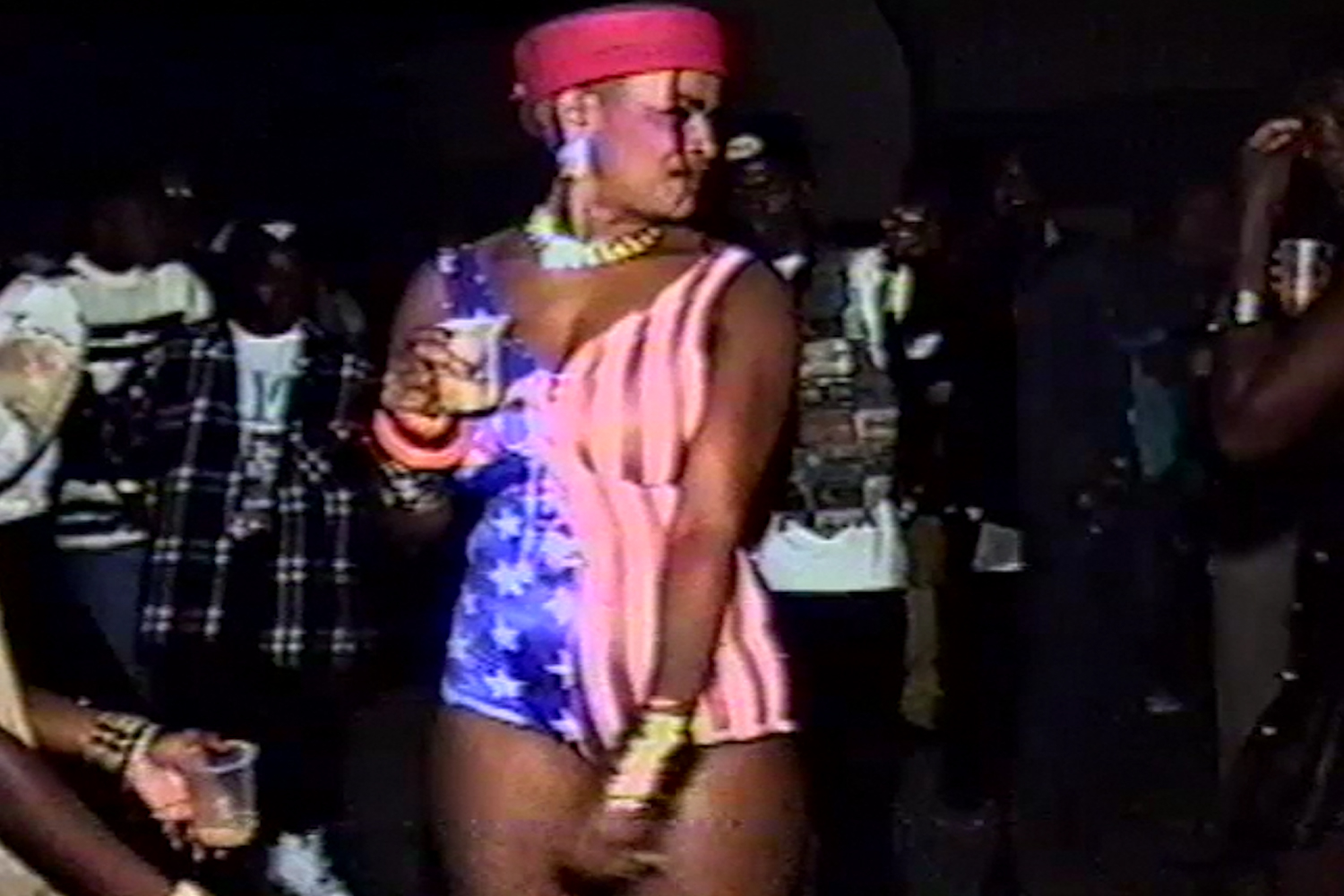

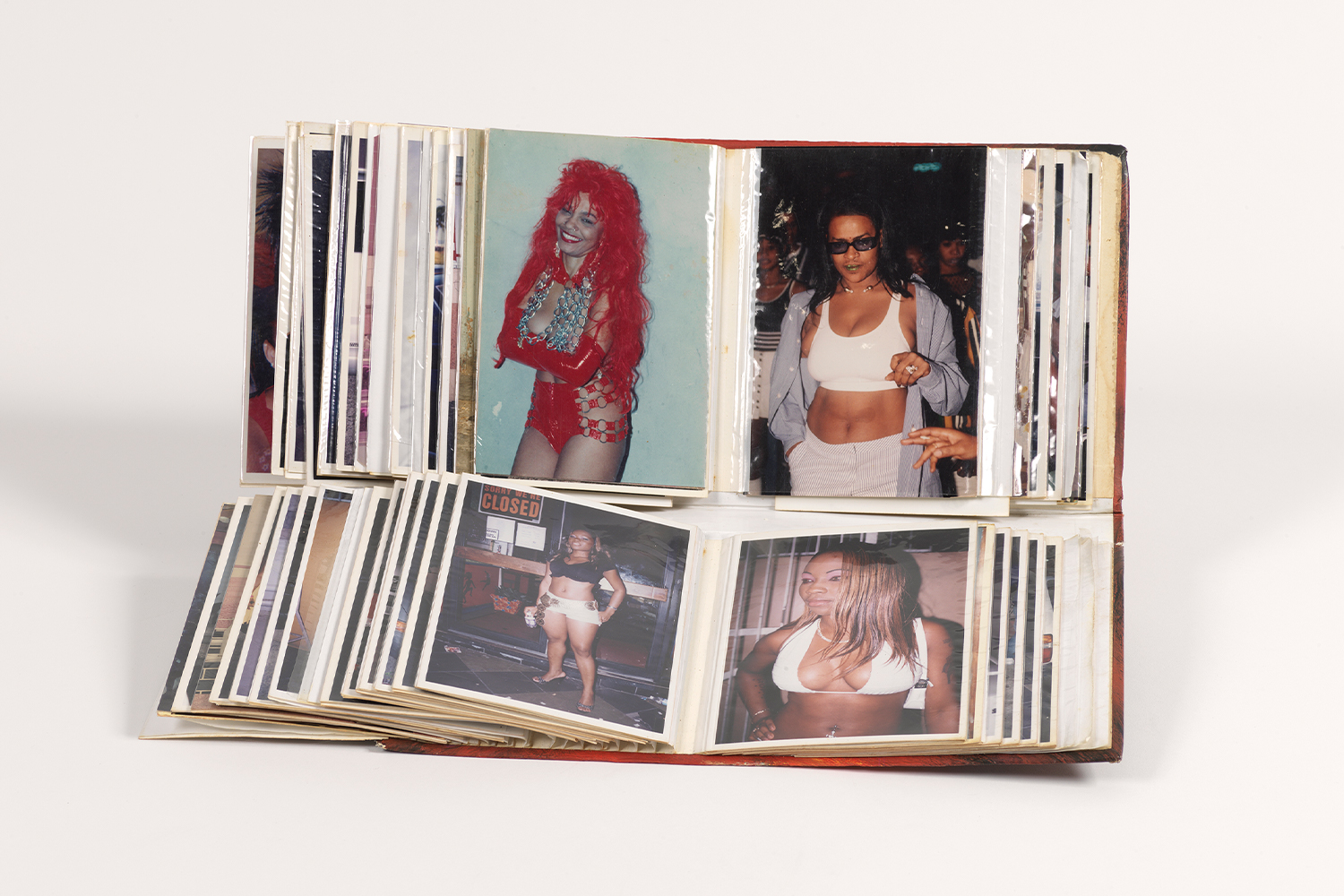

His debut as an “artist” came in 2020, with his first solo exhibition at Red Bull Arts in New York. “No Gyal Can Test” celebrated dancehall culture and the relationship between memory and photography. For Smith, it was a chance to showcase twelve years of archival research, exhibiting a remarkable amount of archived VHS video footage and photographs from the Ouch Collective’s heyday in Kingston from the mid-1980s to the 1990s; as well as a series of sculptures made from salvaged remains of Kingston’s Waterhouse District. Smith utilized and manipulated the imagery of Jamaican clubbing by reassembling remnants of the spaces where parties took place — appropriating walls, doors, and window casings — into true sculptural environments. The short-circuit between the documented and the documentarian was amplified by the exhibition’s set design, which featured scores by Total Freedom and Alex Somers, lyrics by literary scholar Carolyn Cooper, sculptures made in collaboration with Jessi Reaves, and uniforms created with Grace Wales Bonner.

In that exhibition and subsequent productions, Smith adroitly works the friction created by blurring the threshold between the sacred and the informational. Today he is included among the artists participating in the latest edition of the Biennale de l’Image en Mouvement in Geneva, “A Goodbye Letter, A Love Call, A Wake-Up Song,” co-curated by Andrea Bellini and DIS.

In the following conversation, Smith traces with Andrea Bellini the anthropological roots of his research.

Andrea Bellini: Akeem, let’s start this interview with you walking into the Mark Leckey show at MoMA PS1 five years ago. You watch Leckey’s breakthrough film Fiorucci Made Me Hardcore (1999). I read somewhere that this work had a strong impact on you. Is that true? Would you say this work represents a sort of epiphany for your practice as a visual artist?

Akeem Smith: Yes, that piece resonated spiritually and physically. I also saw Dial H-I-S-T-O-R-Y (1997) by Johan Grimonprez around that time. Before watching these pieces I thought of my practice as more anthropological in a sense. As the archive evolved I wanted to explore the material more poetically, a bit more abstractly, as a piece of art, not just a piece of history — freeing the images from a more formal archival reading and chronology. How can I somersault these subjects into protagonists and this documentation into a more nuanced narrative about style and empowerment?

AB: I guess you are talking about your family archive. Can you tell me how the idea of “No Gyal Can Test,” your first major solo show at Red Bull Space in Detroit, came about?

AS: The first iteration of the show came about because I appointed myself as the family’s archivist. I know that my family are very special people. I’m sure there are a lot of people that function the way we do, but it’s not so norm. I had just started working as a stylist assistant, and I thought my family and friends would be great reference points for fashion, costume, and style research. In the end, I wasn’t comfortable using the images in my fashion work for a number of reasons. Because at the time I didn’t consider myself an artist, and I knew I wasn’t a curator — so a big issue for me was, without being either of those things, how do I both preserve and honor this trove? I knew I needed the right space and capabilities to do this right, and so I sidestepped a number of exhibitions that came along over the years that just didn’t align with where my head was at at the time. When Max Wolf, former curator of Red Bull Arts, approached me to do this thing and do it right, I felt like I finally had a partner who could provide the resources and who was not into subduing my vision for this show. I finally had the means and runway to fabricate and mount the ambitious ideas I’ve had in my head for nearly a decade now.

AB: This is the time when you started traveling more often to Jamaica?

AS: I was visiting Jamaica frequently, collecting personal photographs, interior home decorations, fake toenails, videos without purpose or specific intention. I didn’t know what exactly I was going to make out of them. I just gravitated towards the things that felt familiar and foreign simultaneously. My family, the women especially, don’t really play by the rules of the society they come from. Being around that really opened me up to “adulthood” and the importance of being social and the transformative potential of social spaces.

AB: That’s why you put more focus on the women in your exhibition. I imagine they were the central players in the parties. Can you tell me about the ones who have left a deep mark on your imagination. Who were they? What did you learn from them?

AS: I think pointing out just one figure or group would be unfair. Most of the women possessed this attitude that words won’t do enough justice to describe. It’s just something one must witness for oneself. It was good observing and ignoring people presenting the best versions of themselves in real time. I learned that there are people that watch and that there are people that do.

AB: Going through the archive I guess you had the opportunity to consider all the differences between the old dancehall and today’s nightlife. I’m thinking about the issue of image production for example, how the way of making photos has changed, or even the issue of making films. Can you talk about that?

AS: What I noticed for sure was how technological advances caused changes in human behavior. I was interested in the relationship at the dance between the videographer or photographer and the subjects, which was slowly evolving or devolving. The role of the documentarian that exhumes special moments morphed into the “peeping tom.” The footage used in Social Cohesiveness (2020) is from the mid-60s all the way up through the year 2001. I also realized the thing I wanted to archive was something that was more intangible, harder to classify. I was archiving attitudes and swagger, and I was interested in how they evolved amidst a rapidly changing technological and social strata on the island.

AB: If we consider those differences we should assume you’ve been working on something unique and unrepeatable, not only in relation to the issue of fashion, of course.

AS: I think so. There are so many more stories to tell, but the mission remains the same.

AB: Talking about women, your grandmother owned a nightclub in Kingston. Can you tell me a little bit about your childhood memories, which seem to have ended up in your film Social Cohesiveness?

AS: I’m not sure if too much of my childhood ended up in the film. If it did, it wasn’t intentional. It was good witnessing the nocturnal economies of all the people that made the most of their income because of the events that were being thrown. I think maybe how my childhood memories were brought to life in the piece were all the things that I was thinking in my head while simultaneously looking down at the parties from the roof or watching from the tapes, drawing my parallels in my head from what I was learning on a scholastic level, through current events and on the street, and creating denominators and links to how all these things were interwoven with each other.

AB: There’s nowadays a lot of discussion about the political potential of the dance floor. Do you think that niche club culture in general is something that we can share as human beings despite all the differences that separate us? What are your thoughts on it?

AS: I don’t agree or see the truth in that. I do think the club can be a place where one’s identity/ identities can take shape and find an outlet.

AB: This to me seems already an extraordinary political potential. Don’t you think so?

AS: Maybe so. I think identity is one step; what you do with your identity is another thing. I do think that what some of my work affirms, at its most universal level, and especially for a range of audiences during this prolonged pandemic, is the basic human need or desire to gather in a social context. That feels like a particularly human instinct in whatever form it manifests. It’s more primal than political to me.

AB: You started working in fashion when you were about sixteen. Can you tell me about Section 8? Is this a practice that is somehow related to your art practice or do you keep the two of them separate?

AS: I can’t say much about Section 8 right now, but yes, I am a part of it. I’ve always looked at both of these practices through separate lenses, as their objectives are fundamentally different.

AB: Your first solo show is about personal memories and your roots. What about your next project? Are you still planning to work around the archive?

AS: I think it’s fair to say my work will inevitably carry on some sort of archival practice in varied forms, and including a host of shadow archives in addition to “No Gyal Can Test.” There are a couple archives that I’ve been working with lately that I’m really excited to see how the narratives resonate in new mediums and within new frameworks that I’m exploring.

AB: I’m very curious to discover more about the material you are working on now and how you are planning to use it. I really think you have the opportunity to go through unique material, coming from a unique place. I’ve been reading a lot Édouard Glissant recently, an amazing author — born in Martinique in 1928 — that everyone today should read again and again. He wrote that the Caribbean is the place where relations manifest with the most splendor. The Mediterranean is a “sea that concentrates,” an inland sea, surrounded by continents, whereas Greek, Latin, and Jewish antiquity, then Islamic expansion, have generated the thought of the One and have given rise to millenary “atavistic communities.” The Caribbean is a place of encounter and passage in “a sea that diffuses,” which gives rise to “composite cultures born of creolization,” linked “to the conscious and contradictory experience of contacts between cultures.” According to Glissant, human truth is not that of the absolute but that of relationship. Every identity exists in relationship; it is only in the relationship with the other that I grow, changing without denaturing myself.

AS: The more I accumulate, the more I take myself and the materials more seriously. It’s so funny that you mention truth, because I do agree that it doesn’t exist. With my work I hope in the future it can be a cross reference to the new Accepted Truth and Power Truths about Afro/Caribbean visual aesthetics. Having the direct accounts live simultaneously with the digested version. The work will work to contest the historically fixed images of the people and work against the concept of culture erasure.