Agnieszka Kurant’s complex conceptual practice can be described in many ways: as research into the invisible, as a study of algorithmic futurity and digital capitalism, an exploration of living and non-living actants, and the emergence of hybrid geological and biological forms. At the most general level though, Kurant’s practice deals with an expansion of what is traditionally considered the human realm, by highlighting the agency of various nonhuman actors such as data, minerals, insects, bacteria, and collective and artificial intelligence. What is considered human expands through coexistence and collaboration with, other species, microbes, viruses, machines, minerals, and geological processes.

Kurant is part of a larger group of artists who deal with our shared spheres of existence from micro to macro, the molecular to the digital, animal and plant kingdoms to intergalactic spaces. This kind of artistic research looks at the most basic units that form our “world picture” and toys with their possible transformations, often through the crossing of spheres or species. Trevor Paglen, Hito Steyerl, Anicka Yi, and Pierre Huyghe come to mind.

Kurant deploys the agency of different nonhuman entities (from termites to AI, from collective intelligence to slime molds to minerals) to gather and create new, complex assemblages. She might be the aggregator of the components and, in this sense, shapes and directs the process at certain stages by synthesizing and composing the assemblage. Yet the result is not synthetic or artificial but a thing that holds these differing states — organic and synthetic, engineered and naturally reproduced, manufactured and algorithmic — together in a single cohesive unit.

Kurant’s work considers the infrastructure and labor that created the conditions for the possibility of all of these processes involving human and nonhuman agents. She might, for example, reveal the crowds of human workers behind the apparatus of artificial intelligence, thus establishing the crucial contributions of hidden and collective labor in research, technological innovation, and development. Her timely practice asks serious questions about the nature of speculation, the widespread exploitation and enclosure of the commons, and the gross inequality perpetuated by a “data society.”

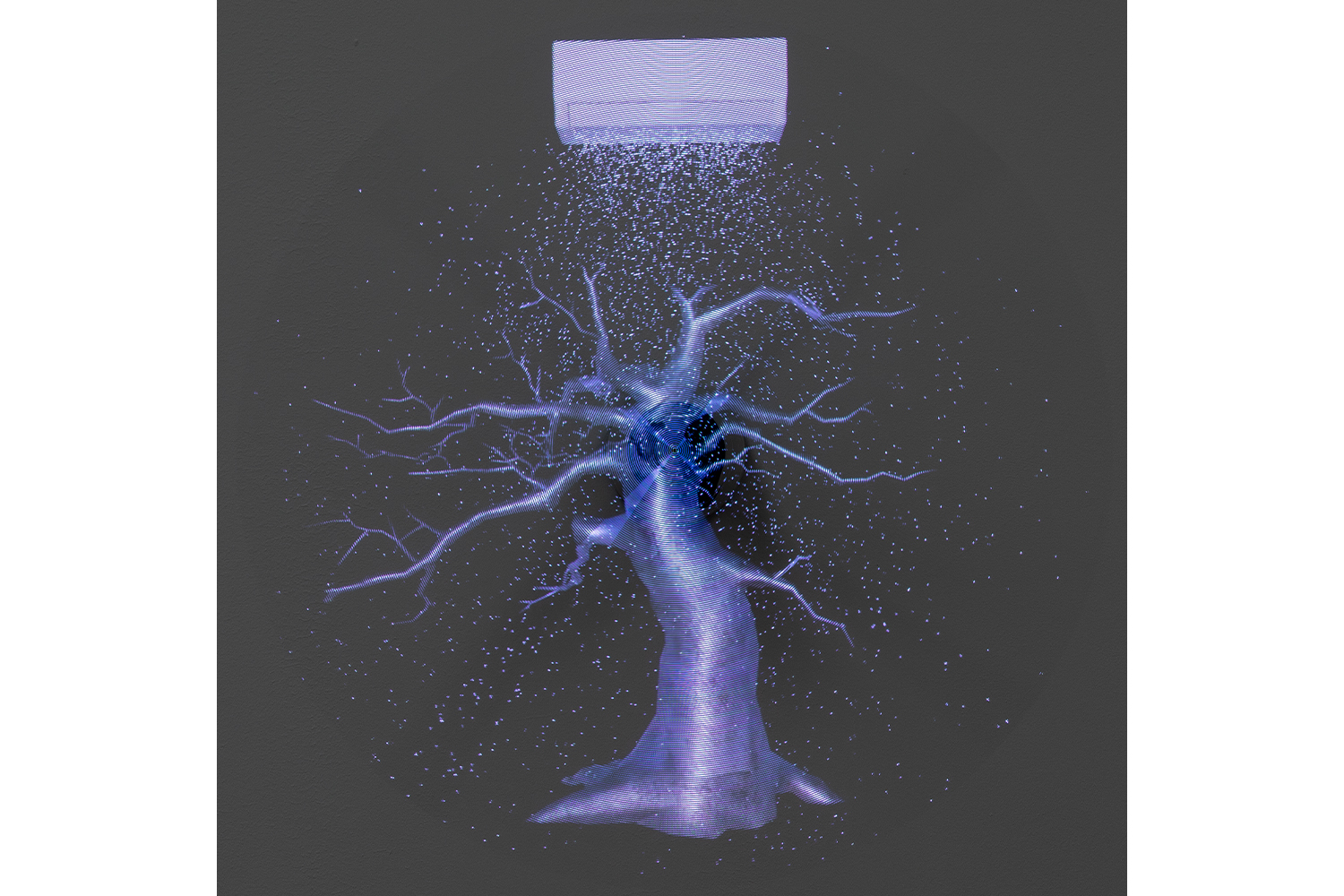

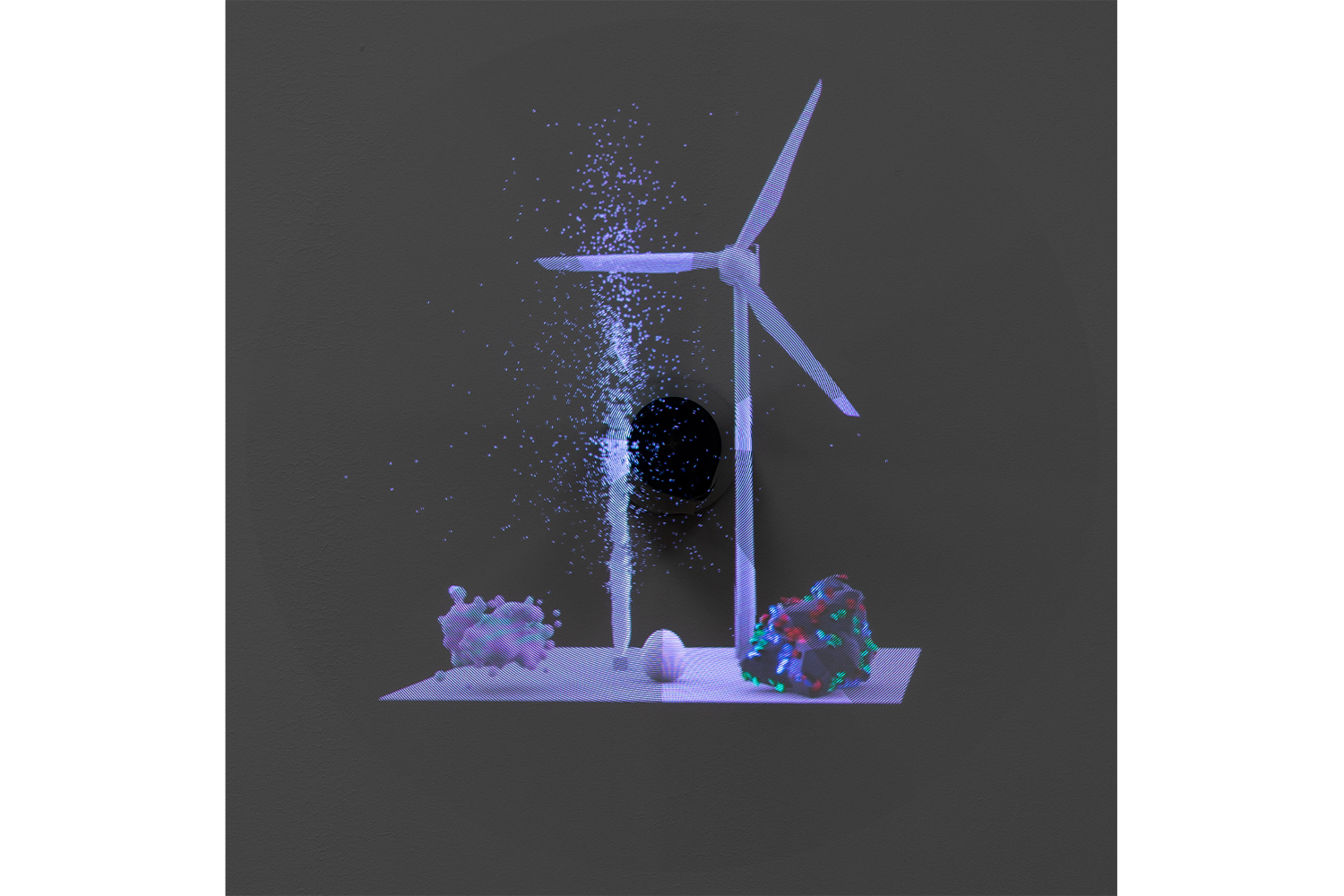

“Errorism” is a neologism that was generated by the AI algorithm GPT3. This algorithm uses deep learning neural networks to create new, human-like texts based on existing publications by a given author and the entire corpus of English language online. Some of the results, such as new texts in the style of Kafka or Shakespeare, were sent to notable literary critics who found them “not bad at all.” Kurant, who consistently collaborates with multitudes of agents or actors in order to explore as-yet-unknown economic contexts, trained the algorithm with a set of descriptions of her own artworks and the essays she had written to date. The algorithm generated a number of descriptions of new conceptual works that the artist never authored but could potentially create. For example, it produced the neologism “errorism” as a title for a potential artwork. The holographic installation Errorism (2021), although not authored by Kurant, is an extension of her labor, practice, thoughts, unconsciousness, dispositions, memories, consumer habits, and search history. It’s an alternative configuration of future forms of her work. Using the example of her own art, Kurant undermines the idea of creativity as an individual endeavor.

As Kurant questions the idea of autonomy, she reminds us that many of the tools she invokes have been developed as means of “risk management” — ways to algorithmically anticipate the future and limit margins of error for the purpose of profit. But it is errors that often generate our most important cultural contributions and discoveries: artworks, medicines, physical revelations, even quantum research. You could say the same for evolution, creativity, and biology. Thus, the neoliberal aim of bringing the margin of error to zero by controlling all possibilities through digital world-making is itself a significant systemic error.

* * *

Noam Segal: Agnieszka, it’s a pleasure talking to you. Thank you very much for your engagement. As a point of departure for this discussion, maybe you could share something about your work processes? Do you think about your work as part of a process that involves many actors? How do you treat pluralities, multitudes, and other agents on an equal basis when their participation results in an object? Or maybe it’s worthwhile to talk about equity in terms of interspecies relations, since the idea of capitalist abuse of human and nonhuman collaborators and invisible labor is central to your practice.

Agnieszka Kurant: The point of departure for most of my works is the realization that creativity and the production of culture is the result of the labor of the multitude and not of single individuals. I am also investigating the new kind of extractivism developed in the digital economy of surveillance capitalism and based on value extraction from the collective intelligence of the entire society. Today the entire society has become a factory for data production and exploitation in which we are all workers.

The political economy in which we currently live was described as “total cybernetics.” Our emotions, decisions, movements, and habits leave digital footprints that are harvested with algorithms and, when aggregated, generate value for corporations and governments.

The worst of all, however, is the fact that in platform capitalism whatever remained of the commons has been ultimately privatized while the affective labor of crowds is constantly exploited. The parameters of commonality — such as exchange, sharing, and participation — are being exploited by corporations, which benefit from the inputs of millions of enthusiastic contributors. Even the museum audience is an object of extraction and outsourcing, as the circulation of images of artworks on social media by viewers increases the artworks’ value. Museum audiences have become collective workers.

Today, even animals have become ghost workers in the late-capitalist machine of exploitation of every currently accessible resource. The phenomenon of “animal internet” identifies more than a hundred thousand completely unaware, wild animals, tagged with chips inserted under their skin and then tracked on animal-tracker apps, which provides, in aggregate, data that can allow us to anticipate earthquakes, tsunamis, volcanic eruptions, floods, and even pandemics. Elephants in Sri Lanka could warn us about future tsunamis; toads can anticipate earthquakes such as the one in L’Aquila in Italy in 2009; tracking the altitude of geese could forecast large-scale avalanches; and an Ebola epidemic could be predicted by fruit bats.

My works reflect on these complex mechanisms of invisible labor and concealed exploitations. I developed an alternative way of producing artworks based on various forms of collective intelligence, collective agency, as an alternative to a single individual author. The concept of the “author” could be seen as a mechanism devised to appropriate value produced in a dispersed and networked creative process, and to extract profits from the general intellect. The emergence of the individual author was part of the process of privatization of the commons. But today, if we look at Wikipedia or Reddit and the circulation of internet memes and crowdsourcing, we realize that they resemble the ways in which knowledge and creativity functioned a few thousand years ago when the Bible and the mythologies were created over the millennia by generations of anonymous authors, by entire societies. The current form of artmaking primes individual authors, but culture might evolve into different, more complex, hybrid, collective forms involving not only multitudes of humans but also machines, minerals, living organisms, and viruses. A polyphony of agencies. That seems like a possible evolutionary change comparable to the advent of writing. And my works speculate about these future potential forms of labor and creativity, the beginnings of which we can already observe today.

I started working with the phenomenon of collective intelligence and with multitudes of human and nonhuman agents in order to undermine the paradigm of individual, singular intelligence and of creativity understood as an individual process. I try to produce forms that elude ontological classification because today we realize that the distinctions between natural and artificial, sentient and nonsentient, real and synthetic, life and nonlife, do not exist or are starting to crumble. The contemporary human is in fact an assemblage, a multitude, or a polyphony of simultaneously operating agencies and intelligences, from the microbes in our gut and the viruses affecting our brains and impacting the decisions we make and our mental states, to the algorithms deployed by corporations automating and optimizing our decision-making, which likely results in the plasticity of the human brain as well as the plasticity of the social brain, as Franco Bifo Berardi and Catherine Malabou, whose work infuences my practice, have been exploring for many years. As a result, the concept of the “self” as a singular, autonomous individual begins to collapse. It is not a single “self” but various forms of plural subjectivity. We have never been singular. Individualism is a capitalist invention, and the idea of “singularity” and the anthropomorphizing of AI as an individual intelligence is just a neoliberal concept forced on us to help with value extraction from the entire society. To give the best example of how AI can also be seen as a result of the exploitation of collective intelligence, we have to understand how machine learning algorithms, such as machine vision algorithms, are trained based on the inputs of millions of humans — not only the ghost workers of crowdsourcing platforms such as the Amazon Mechanical Turk but also anonymous, unaware, and unremunerated internet users. The machine-learning algorithm is a collective intelligence involving both the exploitation and voluntary participation of millions of people. For example, all the users of the English language online contributed to the training of the GPT3 algorithm.

Some philosophers, such as Matteo Pasquinelli, describe machine intelligence and AI not as anthropomorphic but as sociomorphic. It essentially mirrors social collective intelligence, and therefore it uses similar mechanisms of social control.

In order to talk about these questions, I developed a way of producing forms based on complexity and the phenomena of collective intelligence and emergence. I started to grow or evolve artworks like living organisms or geological formations or new languages, crowdsourced to the collective intelligence of thousands of nonhumans and human agents. I create assemblages or polyphonies of intelligences and agencies involving molecules, bacteria, animals, viruses, geological processes, synthetic organisms, online workers, social movements, AI neural networks, robots, chemical and physical reactions, as well as processes of profit sharing and redistribution of capital. This leads to the production of hybrid forms oscillating between different states and realms, evolving or dissolving. Between natural occurring formations and sculpture, between real and synthetic processes, between artificial and natural products, between human and nonhuman, between nature and technology, between life and nonlife, between singular and plural subjectivity. Essentially the distinctions and boundaries between these realms have already permanently dissolved.

Quite often I’m not working with the form of the artwork but with the molecular composition of matter or with the organization of a system or ecosystem that crystalizes forms. These forms are often unstable and evolving. Many of my works are produced by multitudes or complex agencies. My work process consists in either identifying or creating systems that result in the emergence or crystallization of forms. I simply set up a system or program and deliberately lose control over the process.

I started to observe parallels between the ways in which different forms crystallize and emerge in living systems, in geology, and in society: a mineral crystalizes in a similar manner to a sign, a tool, a rumor, a currency, a meme, a crowd, a social movement.

I have been looking at the crystallization of civilizations, revolutions, migrations, pandemics, or cities on a par with swarms, dunes, slime molds, termite mounds, and waves, as various forms of collective intelligence and emergence.

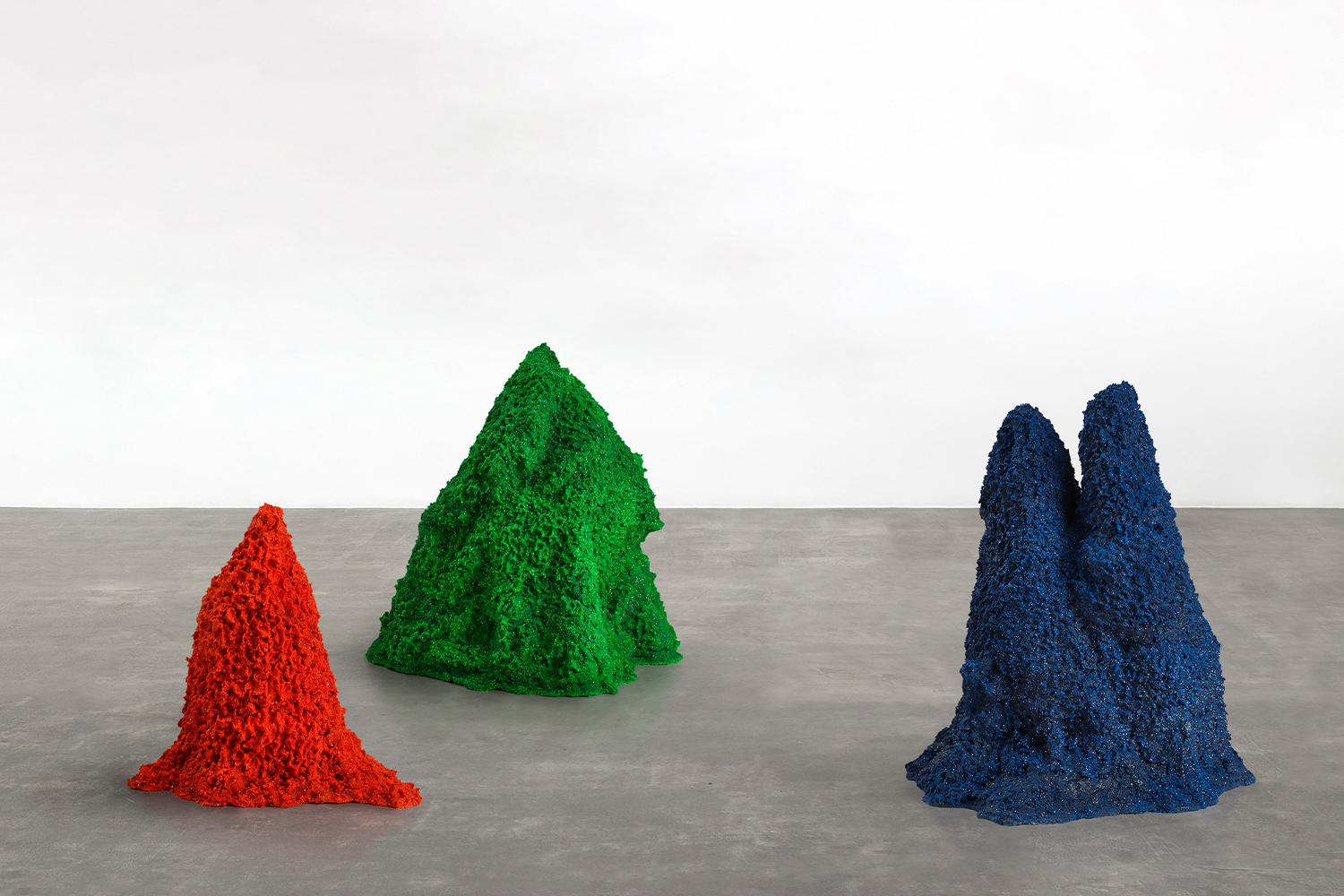

Works such as A.A.I. (2015-2017) are built by entire societies — in that case societies of termites. I grow them like geological formations. Each of these natural-artificial mound forms consists of millions of grains of colorful sand, gold, and crystals, amalgamated together by millions of living organisms, and the final form is a product of this collective intelligence.

My other works are based on amalgamations or aggregations of social capital — for example, The End of Signature (2020) is an aggregation of thousands of signatures of members of one community or one social movement, fused together by an AI algorithm. Other crowdsourced works, such as the series Production Line (2016–17, co-authored with John Menick) or Aggregated Ghost (2020), are based on aggregations of the labor of thousands of online workers on crowdsourcing platforms —so-called ghost workers, who contribute single lines or selfies that I fuse with AI into composite, compound forms.

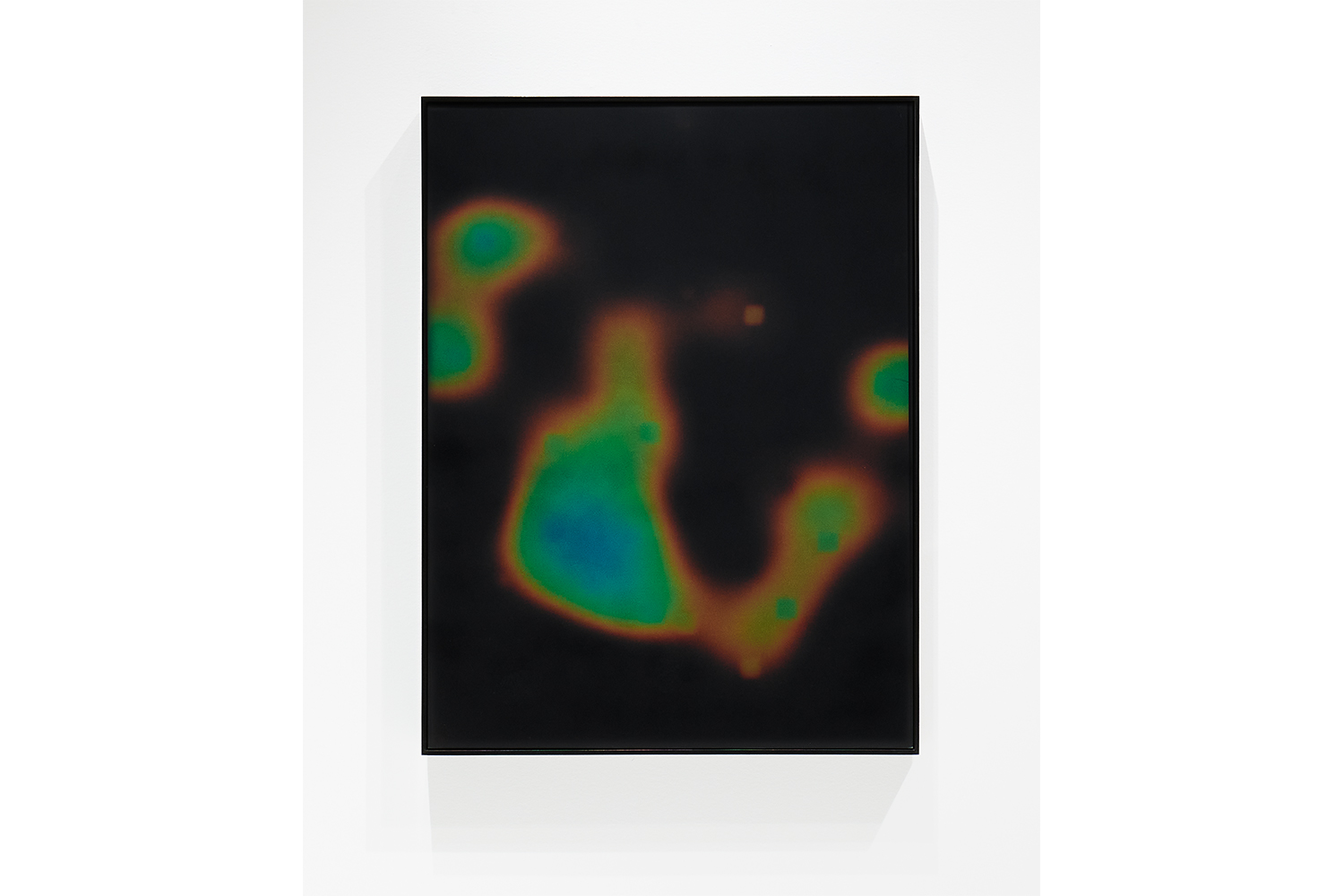

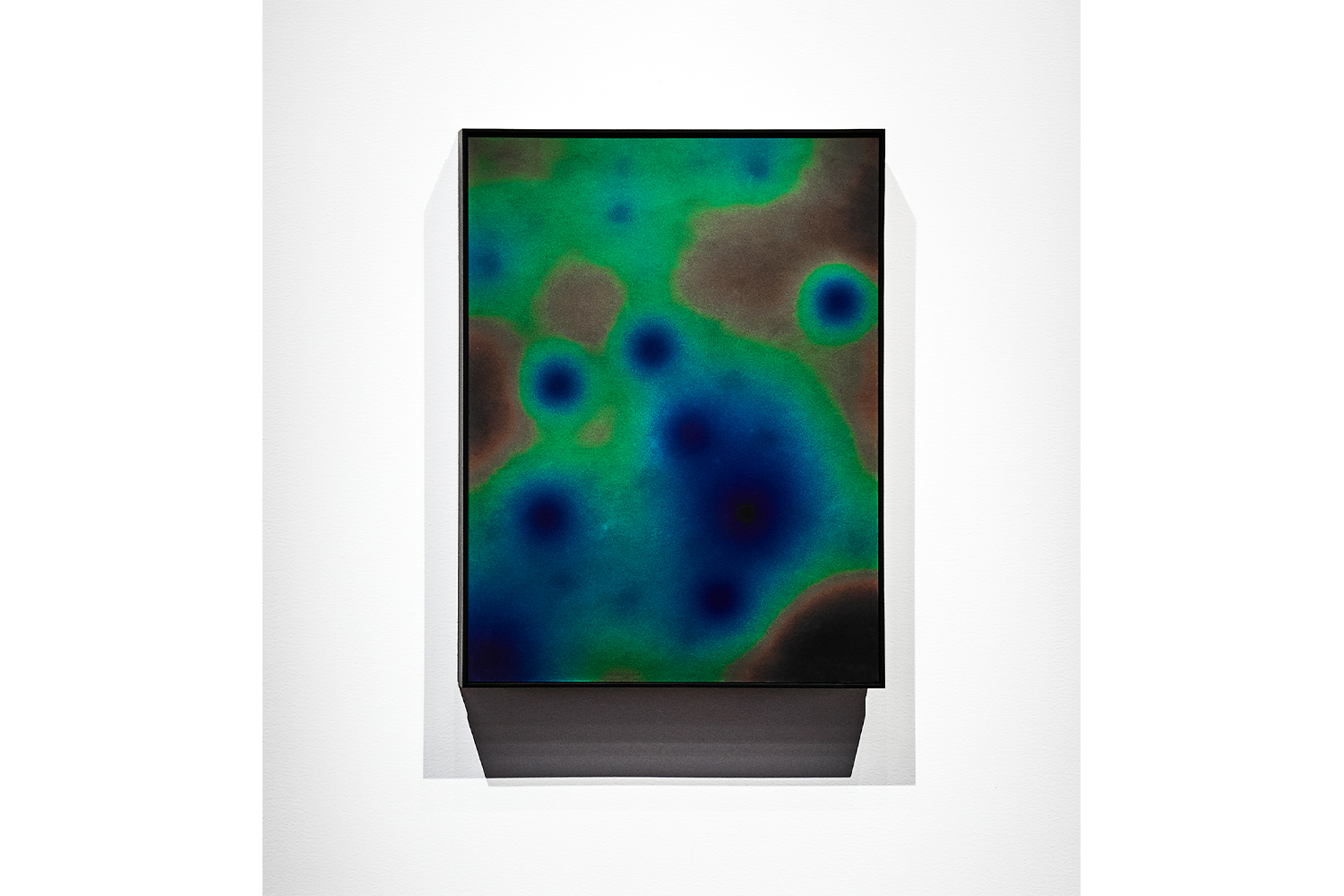

Many of my works explore various kinds of human footprints and mutations of matter. Conversions (2021) use AI to harvest and aggregate emotions or digital footprints of thousands of people around the globe: the members of protest movements. These works explore the relationships between the changes in the world and the physical changes in the artwork. The digital footprints left by millions of people making decisions or expressing feelings in the real world have an impact or cause physical changes in the molecular materiality of these works. Each of these ever-morphing liquid crystal paintings is based on the harvesting of emotions — joy, fear, anger, enthusiasm — expressed on Twitter by thousands of people: the members of protest movements around the globe, which I chose since today even our protests against the status quo are harvested by corporations and immediately monetized. Each painting is an embodiment of opinion dynamics around social change and an entire complex interplay of agents of change dispersed in society.

And Post-Fordite (2020) is a side effect of the amalgamation and a quasi-geological footprint of the labor of thousands of workers at the production lines of now-defunct car factories, in which layers of automotive paint fossilized over the years into hybrid rock formations.

Some of my works relate to the current obsession with algorithmic risk prediction and error elimination. Digital capitalism treats not only current but also future states of nature as quantifiable, computable, and configurable resources. These possible futures can be calculated, hedged, simulated, valorized, and monetized. Digital cognitive capitalism trades in nonexistence: today not only have concepts, copyrights, patents, air rights, and debts become invisible products, but futures of various kinds also become objects of speculation. From financial futures to algorithmic risk management futures to the future of as-yet-nonexistent branches of industry such as asteroid mining, upon which people are already hedging. And my new work Errorism pushes this idea of algorithmic prediction and financial speculation on futures to an absurd point. In a way I have self-exploited myself by mining data about my past works to produce a work that is a certain optimization or reconfiguration of my work. The algorithm GPT3 produced an adjacent potential to my existing works, possibly censored by my unconscious. It is an algorithmic speculation about my future or alternative works. But what is really important is the fact that, thinking broadly, the author of the descriptions of these phantom works is the entire corpus of human language processed through GPT3. All the users of the English language online contributed to the training of GPT3. So, there is a tiny bit of agency or data or labor of millions of people behind the generation of these new descriptions, which led to the forms that I developed as a hologram. My choice of hologram is deliberated here, as these forms are mere phantoms of works; but in the current economy of cognitive capitalism, which trades in nonexistence, these holographic forms are not dissimilar from other invisible or phantom products or objects of speculation. Today it is possible to hedge on anything, including future scientific discoveries and artworks that haven’t been created yet. Errorism presents such an algorithmic speculation about something that is not my own work but highlights the complex agency of the multitude present in any artistic creativity.

* * *

NS: You have said that society currently functions as a “giant factory of data production and exploitation.” In several works, like The End of Signature (2015-2021), Conversions (2020- 2021), Phantom Crowd (2021), or even Cyber Key to Dreams (2021), you harvest this collective data to create joint simulations of crowd representation, aggregated signatures, or a collective unconsciousness. Basically, by subverting the mechanisms of neoliberalism, you offer a comprehensive representation that on the one hand challenges the notion of individualism and individual profit, and on the other is an action that erases difference or particularity. Are you concerned that such a mode of criticism might reproduce the problems that it seeks to address? How do you avoid simply setting up a dialogue between general images and commodities rather than a genuine interaction? Your work seems to consistently avoid a seamless integration into a consumerist aesthetic, and I wonder what choices you are making to differentiate it from pure spectacle.

AK: I try to employ various subversive strategies such as outsourcing, crowdsourcing, and redistribution of capital to undermine the existing paradigms and exploitations of labor and creativity. Although some of my works resemble monuments built by the entire social factory, but this factory is always twisted, as the workers are nonhuman entities: animals, bacteria, molecules, or algorithms. My works are created by multitudes of agencies and intelligences. For example, the termites, which build the A.A.I. sculptures, are half-blind, so I simply trick them into building their own homes from alternative materials: colorful sand, gold, and crystals. Although these animal societies are completely unharmed by becoming my workers, I take advantage of them, pushing the idea of outsourcing to the point of absurdity.

In other cases, with the drawings, paintings and sculptures crowdsourced to thousands of people around the globe, I am redistributing profits among workers or social movements.

One of the questions that I have been experimenting with is how to develop forms that are based on equity, not just a discussion of equity, exploitation, or inequality. That’s why I work with forms of redistribution and profit sharing, in order to go beyond the existing paradigm of physical artworks, the sales of which benefit only a very small group of people. Works such as Aggregated Ghost and Production Line allow me to syphon off money from the art market and redirect it to online workers — the ghost workers of the crowdsourcing platforms. Whenever any of these works is sold in the art market, the workers share in the profits via a bonus system. This allows for the redistribution of capital among the members of this emerging and exploited online working class. Similarly, the profits from Conversions are redistributed among the protest movements that I earlier mined for data. Conversions explore the relationships between the changes in the world and the physical changes in the artwork. The digital footprints left by millions of people making decisions or expressing feelings in the real world have an impact or cause physical changes in the molecular materiality of these works. Each of these ever-morphing liquid crystal paintings is based on the harvesting of emotions — joy, fear, anger, enthusiasm — expressed on Twitter by thousands of people: the members of protest movements around the globe, which I chose since today even our protests against the status quo are harvested by corporations and immediately monetized. Each painting is an embodiment of opinion dynamics around social change and an entire complex interplay of agents of change dispersed in society. When the painting sells, the profits are redistributed among social movements. This way I am cynically using the machine of value production created by the art world to generate funds for social change.

In Conversions and Phantom Crowd, I explore the use of crowds and crowdsourcing in the contemporary economy. The crowds of living bodies become assets of surveillance capitalism. Contemporary crowds are evolving into new, mutated forms. The aggregated value of collective intelligence and social capital of a given crowd can be quantified and valorized very precisely with algorithms. On top of this we have troll farms and chat bot armies, which are basically phantom, simulated crowds for hire.

New technologies have enabled increasing capacities for social mobilization and political agency, but digitally mobilized crowds are also easily manipulable, controllable, and predictable with social simulations such as “artificial society” — a multi-agent artificial intelligence model that I employed earlier to create Conversions. Phantom Crowd proposes a holographic simulation of a controllable crowd, reacting to various inputs from social phenomena in the real world. After parsing millions of images of real crowds, the AI neural network produces new images of nonexistent synthetic phantom crowds that evolve over time.

In various iterations of The End of Signature I was exploring the ways in which social capital can play a more significant role than financial capital. Companies and governments constantly compute the value of our aggregate social capital, but I am proposing that we can use the same algorithmic tools to precisely calculate the value of our own capital, or how to induce social change and increase altruistic behaviors in society. We can calculate how much our attention or our invisible work on social media platforms is worth, and how much political currency is accrued in a neighborhood where everyone, discouraged by their lack of impact on politics, completely stops voting in elections. At the Guggenheim Museum, for example, I aggregated the signatures of visitors as museum audiences today contribute to the value of exhibited artworks by circulating images online. In other iterations of this work I produced collective signatures for various social movements or workers’ unions, considering them as super-organisms or collective persons with personality traits. For the current commission for the MIT List Visual Arts Center, realized on the facades of two new buildings on the MIT campus, I worked with Katie Lewis, Divya Shanmugam, and Jose Javier Gonzalez Ortis – as well as their advisor, Professor John Guttag in MIT’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Lab, to aggregate thousands of signatures of scientists and academics as well as students working at MIT, both in the past and currently. I wanted to draw attention to the question of the privatization of knowledge as part of the privatization of the commons. Scientific discoveries are not the result of work by individual genius scientists, financed by corporations, venture capital, and rich universities, but are built on the labor of multiple generations of scientists or teams of scientists, or that of several scientists working simultaneously in various parts of the globe on the same subject at the same time. Only some of them are lucky enough to obtain funding for their research or gain recognition for their work. So, by signing the new MIT building with the collective signature of all the scientists, academics, and students who ever worked at MIT, I am highlighting the labor of the multitude, not only scientists but also anonymous interns, uncredited students, and post-docs.

Similarly, in Emergent Alphabet (2021) I also discuss the gradual privatization of the commons as exemplified by the privatization of knowledge and design. This piece employs a new typeface, which I recently developed with the typographer Radim Peško. This typeface-artwork uses the history of typography as a gene pool. We used twenty-six typefaces from the history of typography since its beginning in ancient Rome by thousands of anonymous stonemasons of the inscriptions on the Trajan Column, to contemporary digital fonts owned by corporations like Microsoft, including the digital version of the Trajan font. Each letter is composed of fragments of a given letter derived from the twenty-six various typefaces. These combinations produce mutations and errors resembling living organisms.

* * *

NS: In a new piece, Chemical Garden (2021), you worked with a chemist to grow new forms with sodium silicate, copper, nickel, cobalt, chromium, manganese, iron, and zinc salts. Chemical gardens are a set of complex crystalline structures resembling plants created through a mix of inorganic chemicals. The installation, therefore, blends the digital, biological, and mineral. As you told me, the first documented chemical garden was created by the German alchemist Johann Rudolf Glauber in 1646. Modern research shows that chemical gardens in hydrothermal vents on the seafloor (brine and methane pools) are a plausible path for the origin of life on Earth. Even today, those sea basin “lakes” are toxic to their immediate environment, but at the same time they enable the creation of new bacteria and new forms of life. Your research also suggests that some of the earliest fossils of life forms might be from fossilized chemical gardens.

In many other works, such as A.A.I. (2017), Conversions (2020-21) Risk Management (2020), or Collective Rorschach Test (2019), you deal with an idea of growth that can play out in many possible directions and juxtaposes many forms of growth: financial growth vs. natural growth for example. The more complex models of growth that you offer are not limited to growing in one direction or dimension but rather contain this idea of a more rhizomatic growth or a form of growth that extends in unknown directions. Can you talk about how you see this concept unfolding in your work?

AK: My point of departure is the questioning of the neoliberal paradigm of growth based on human exploitation and environmental destruction, and the necessity to replace it with the paradigm of degrowth, based on social justice, ecological sustainability, self-organization, and the rebuilding of the commons and the collective subjectivity. For that reason, I am researching alternative ways of developing or growing forms based on collective intelligence, emergence, self-organization, and nonlinear system dynamics. Chemical Garden was a way to discuss the fact that evolution is not a linear process. What interests me, for example, is the fact that metabolism is not limited to living organisms. Metabolism circulates and generates new forms in all strata of matter. Organic and inorganic substances are continually reorganized into various forms. And today mineralogists are talking about “mineral evolution” in which networks of matter and energy flows are connecting living organisms to minerals. So organisms and minerals are no longer clearly separated. This radically changes the field of what is considered life. Ecosystems are created by the coevolution of minerals with life. And nowadays it is also ourselves who influence the formation of new minerals and geological formations. It fascinates me that the circulation of elements and chemical compounds in some cases creates connections between long-extinct species, species living today, and species from the future. So new life forms created by synthetic biology will have an impact on the minerals of the future. Circulation as a form is very interesting to me because networks of matter and energy flows can be observed both in natural and cultural systems.

I generated Chemical Garden in a way similar to how I grew A.A.I. — in a nonlinear and uncontrolled growth process. A.A.I. is based on the emergence of a termite mound out of the collective intelligence of a termite colony consisting of millions of termite specimens. Chemical Garden is based on the emergence of plant-like forms out of inorganic chemicals: metal salts. These metals — the same ones that are currently used to produce computers, the industrial extraction of which causes entire ecosystems to collapse — were the elements that were necessary for the inception of life on Earth. This is a perfect example of how inorganic chemicals circulate in the world to produce life forms or cause destruction. The fact that these plant-like forms emerge from the interactions of molecules of these otherwise destructive metals displays the complexity of processes in the world and the blurring of the boundary between life and nonlife, between real and synthetic, natural and artificial. Today the mineral, the biological, and the digital are completely intertwined and entangled. Contemporary scientists are harvesting the work of bacteria that metabolize metal and plastic while new organisms are being built from scratch at synthetic biology labs. Non-carbon-based life might already exist on other planets, or it might soon be grown in synthetic biology labs. The neoliberal concept of growth as a linear process based on progress and oriented toward the future is simply wrong. And the complexity of processes present in both biology and geology prove that.

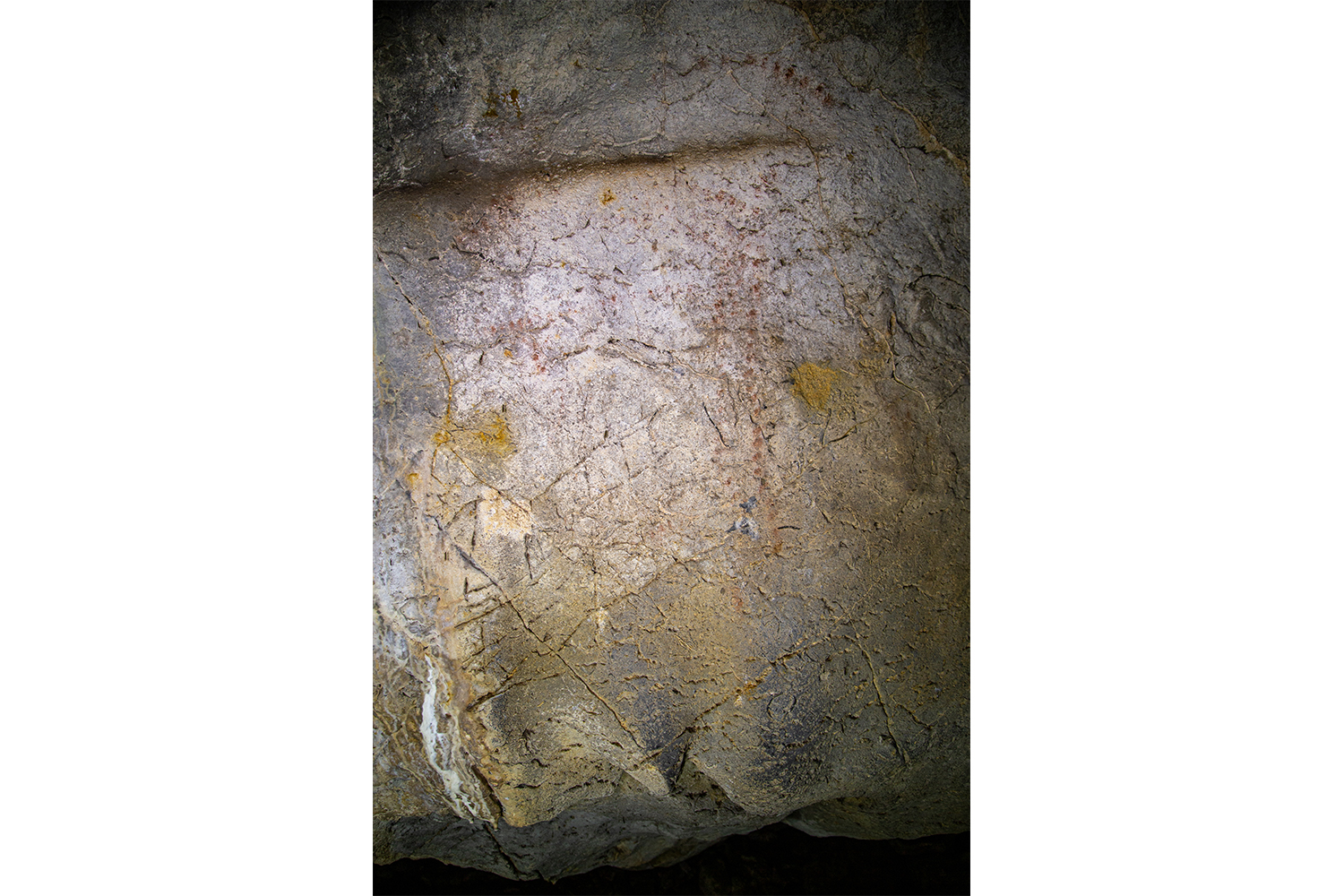

NS: I want to ask about temporality in your work. Works like Post-Fordite (2020) or Liquid Modernity (2021) look into the past. Their concepts or materials are anchored in history and they also locate their intervention in the space of the past. In other works, like Conversions 3 (2021), where you create abstract color fields on copper plates, you are dealing with the present. This work presents an abstract image of a deep and dynamic color field that reacts to the opinion dynamics and changes of emotions among the members of protest movements on web-based social platforms. In other types of works, like Adjacent Possible (2021), you use prehistoric objects as a means of projection or a way of intervening in the future. This work combines one of the oldest technologies and forms of human expression (Paleolithic ochre painting) with AI neural networks. The point of departure is the recent Paleological discovery of thirty-two uniform, geometric signs that recur in various Paleolithic caves (40,000 BC to 10,000 BC), discovered and documented by the paleoanthropologist Genevieve von Petzinger, who has codified these ancient markings across Europe and parts of Asia. The work Adjacent Possible explores these first Paleolithic signs and early forms of human intelligence. You also collaborate with synthetic biologists to develop new pigments using mutated bacteria, fungi, and slime molds as living pigments applied to rock fragments. This results in new signs made by those organisms that could be applied as part of these “living pigments.” The intentionality of the bacteria and the AI dictate this “wall painting” progress.

These works present complex temporalities. Adjacent Possible is geared toward the future, but it’s based on predictions and historic excavations. Can you elaborate on how alternative temporalities play out in your work, and why you choose to direct them the way you do?

AK: What resonated profoundly with my work and impacted the forms I work with were different concepts of technical objects that emerged over the past twenty-five years. For example, Michel Serres’s concept of polychronic, multi-temporal objects, specifically his example of a technical object, a car, as an assemblage of various scientific solutions and techniques from different epochs, drawing from the obsolete, the contemporary, and the futuristic. Bruce Sterling writes about atemporal objects, with the example of the turbine invented by Hero of Alexandria — the aeolipile — which was this futuristic, rapidly revolving object, a gadget or toy with no useful application in the ancient world. It only found an application thousands of years later in a steam engine. Sterling also coined a useful neologism, “spime” — a contraction of “space” and “time” — which is a futuristic object that can be tracked through space and time throughout its lifetime, like the objects of the Internet of Things.

Both Bernard Stiegler and Yuk Hui, whose writings influenced my work, talked about the emergence of digital objects as assemblages that can be tracked in time and space and are part of a network of collective intelligence. Digital objects are oriented to the future, constantly in the process of renegotiating their relations with other objects, systems, and users within their milieux, their environment, which is both natural and artificial. They are not able to function on their own without the activities of the human beings who create and modify them.

On the other hand, today we have other concepts of atemporal objects, such as the “arche-fossils” of Quentin Meillassoux or hyperobjects of Timothy Morton.

Many of my works, Adjacent Possible, Errorism, Post-Fordite, Still Life, and Fossilized Future (2019), try to embody these kinds of polychronic objects. I think that in the near future the nature of cultural products might change: artworks, films, or books may not be considered finished products, as artists, writers, filmmakers, as well as readers and audiences, will be able to continuously change and update them in real time. There will be no fixed forms, which we can actually observe already today with the perpetually evolving technical objects constantly updated by their creators and users and with internet memes accumulating new inputs through circulation, like snowballs.

The forms I generate try to capture the fact that objects in the world have no fixed identity; they constantly oscillate between artificial and natural, life and nonlife, sentient and nonsentient, synthetic and real, fiction and reality, impossible and probable. What was unthinkable or considered science fiction yesterday seems very real today. Contemporary science measures the so-called “half-life of facts,” the pace at which what we considered as scientific truth is disproved and turns into a fiction. Every single day we are witnessing how objects of knowledge transform, evolve, and change their status. My work tries to embody these evolving, unstable objects of analysis of knowledge as they constantly mutate or dissolve. Objects in permanent flux, permanent plasticity, or evolution. That is why some of my works physically change their forms in response to changes happening in society.

I am experimenting with hybrid forms that present diachronic atemporal circulations and fusions, mutations and alchemic transmutations of organisms, minerals, and technologies, from the past, present, and future. The works Hyperobjects (2017), Mutations and Liquid Assets (2014), Liquid Modernity, Fossilized Future, and Post-Fordite are certainly about this constant remolding, conversion, and transmutation of energy and matter.

I think about the production of natural or social forms as different expressions of matter-energy in flux, along Deleuze and Guattari’s notion of the “machinic phylum.” I work with energy as a substance in motion. What interests me is the fact that the contemporary global economy is also based on flows and conversions of energy, which is transformed into information and into capital.

While my work Errorism related to possible futures, which can be calculated, hedged, simulated, valorized, and monetized, Adjacent Possible relates to the computation of possible alternative pasts and the ways in which our civilization could have evolved differently if we’d developed other “first signs.” AI machine learning algorithms allowed me to generate precisely that: alternative versions or reconfigurations of the so-called “first signs” produced by early humans in caves and discovered by paleontologists. I am working with the scientific director of the Center for Modeling Social Systems in Kristiansand, Norway, LeRon Shults, and the computational social scientist Justin Lane, who both utilize multi-agent artificial intelligence to study the mechanisms of social change in human societies. For Adjacent Possible they are helping me analyze thousands of geometric signs left by early humans. These signs were catalogued by the paleontologist Genevieve von Petzinger, with whom we are collaborating. My idea was to explore alternative directions in which human culture could have evolved and where it is currently evolving. I am interested in exploring the “adjacent possible” of these first Paleolithic signs and these early forms of human intelligence. What would our civilization look like if we developed different signs? In what direction would we evolve? In what other new direction is our species currently evolving as we manipulate DNA to produce new life forms, while algorithmic automation of human decision-making causes the plasticity of the social brain?

The biologist Stuart Kauffman talked about the adjacent possible — a kind of shadow future, hovering on the edges of the present state of things, a map of all the ways in which the present can reinvent itself. For example, the evolution of life has explored only a very small fraction of possible proteins, only a tiny part of the “protein space,” and there is plenty of room for synthetic, human-made forms of life or forms of life that can spontaneously emerge in response to, for example, climate change. Ecosystems, economic systems, and cultural systems may all evolve or bifurcate in various directions. But today corporations and governments use computer stimulations such as “artificial society” to predict these future transformations and evolutions and capitalize on them.

Von Petzinger studied thirty-two signs popular in the Upper Paleolithic period of the Ice Age (from 10,000 to 40,000 years ago). These signs may even have been some sort of early sign language. They were the earliest human attempts to store information outside of an individual, to pass that information onto larger groups of people and to preserve it.

It turns out that the ability to not only express thoughts as signs, but to preserve and transmit messages beyond a single moment in time, may be much older than we think and may be the precursor of our first writing systems. For example, northern Spain’s “La Pasiega Inscription,” which dates back roughly 16,000 years, features a number of signs strung together. It might be a very early attempt to create a more complex message.

Adjacent Possible, developed as part of my commission for Castello di Rivoli in Torino, consists of training an AI neural network on a dataset of thousands of photographs of various iterations of the thirty-two Paleolithic graphic signs from caves across Europe and Asia. The AI then produces other potential signs, the “adjacent possible” of early human forms of expression or symbolic communication. These could be signs that existed but were simply never discovered by scientists, or forms that could have potentially evolved but did not, which resulted in the particular line of evolution of human culture that brought us to who we are today. The results of my experiments will subsequently be analyzed by paleontologists, archeologists, linguists, semiologists, and cultural theorists, and will form part of the project. These new signs will be executed with “living pigments,” mutated bacteria, slime molds, and fungi as well as synthetic organisms built from scratch.

* * *

NS: What methodological biases do you find yourself negotiating most often in these collaborations with scientists?

AK: In Adjacent Possible I wanted to investigate the inherent bias of the methodology of science and the frequent myopia of anthropology, paleontology, and other sciences, which often construct narratives based on fragmentary evidence, while ignoring the possibility of the existence of hitherto undiscovered signs and other forms created by prehistoric humans.

Many of my works investigate systemic errors, which are various errors of collective intelligence. In particular, I am interested in the systemic errors we are not aware of. I think about “errorism” as a certain paradigm in which we used to live, which was based on accepting both the destructive and the creative role of human errors. Errare humanum est: erring is human. But neoliberal attempts to completely eliminate errors with algorithmic risk prediction are themselves a systemic error because most of creativity happens precisely because of erring. Evolution is “creative,” it produces new forms precisely because of the errors in DNA replication. Similarly, many scientific discoveries happen by accident, by error. X-ray, aspirin, and Viagra were discovered by accident. The very idea of eliminating errors is absurd because it will annihilate the possibility of exceeding the status quo, the existing paradigm.

Needless to say, algorithms are always biased because data collection is already biased. Systemic errors lead to biased data collection and the creation of biased algorithms. The notion of a neutral algorithm is as absurd as the idea of the internet as a neutral free space. The internet is a largely privatized and surveilled territory.

NS: Lastly, I want to ask you about the exhaustion of human experience. A lot has been said about the impact of technology on human experience. It seems as if, to borrow a phrase from Freud, civilization is increasingly discontent. And yet, we are increasingly confident of outcomes and our capacity for material control. The increasing insistence on absolute clarity and quantifiable measures in the face of existential, ecological vulnerability is a fatal contradiction that diminishes difference as it homogenizes everything in the name of detectability. Most of your work is based on patterns. Like statistics, predictions, and other risk-management algorithms, the future seems dictated by old behaviors, errors, and patterns. This gets more concrete when thinking about the Cyber Key to Dreams (2021). What happens when we base future knowledge on past dreams of the collective unconscious? How can we look at human patterns and assign them to the future while acknowledging the fact that the very notion of what it means to be a human subject is located in individual instances of divergence from these very patterns?

AK: I am interested in patterns, but at the same time the optimization and automation of our decision-making is really disastrous, as it leads to homogenization and discrimination. In a world where everything seems computable and predictable with algorithms, I got interested in uncomputables. It was humbling for me to realize that collective intelligence to some degree eludes algorithmic prediction. In the case of human collective behavior it is often uncomputable because of the fact that, contrary to the neoliberal idea of the rational homo economicus, humans are very irrational and often act illogically, even against their best interests. That’s why predicting complex social phenomena such as revolutions or uprisings, or the results of collective decision-making such as elections, has been so difficult. That is why many of my works relate to the seemingly uncomputable and irrational aspects of reality. Risk Management, for example, presents a map spanning one thousand years of social contagions based on fictions, such as laughter epidemics, collective delusions, asteroid panics, and UFO sightings. These irrational behaviors spread like epidemics but are much more difficult to predict and control. And many of my projects focus on these irrational uncomputable phenomena.

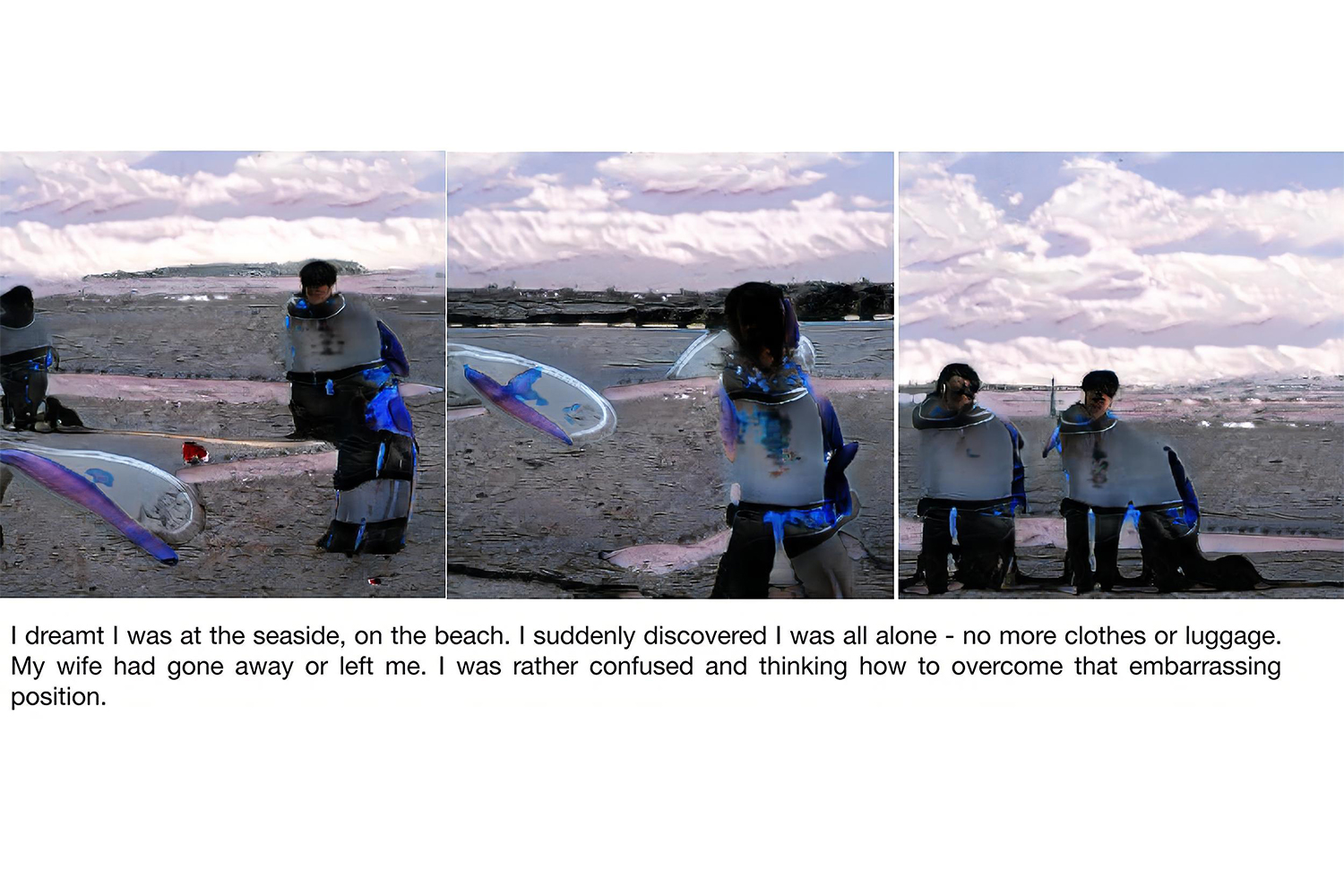

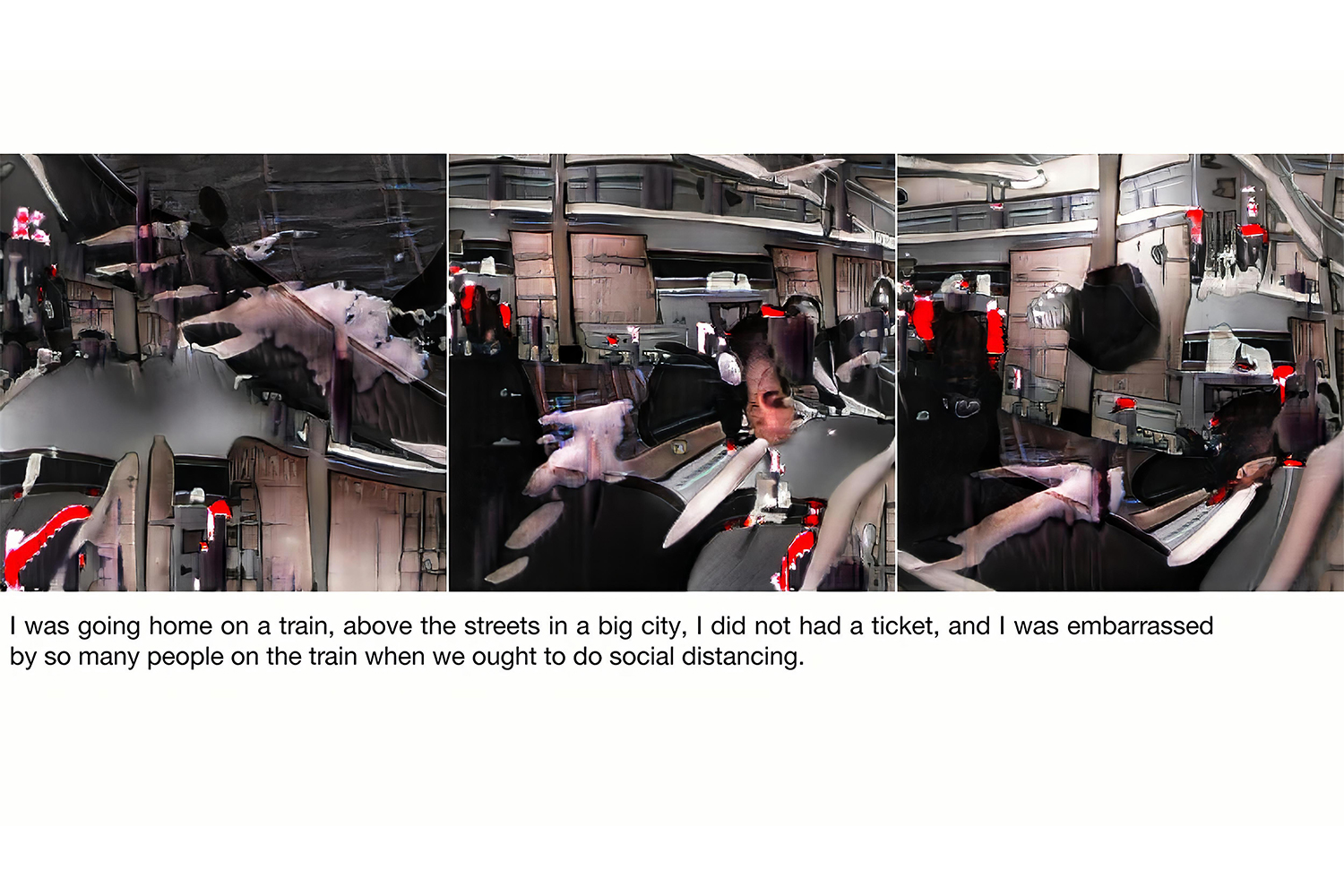

Surveillance capitalism tries to colonize every single aspect of our lives. We thought that our dreams were among the last private territories resisting colonization by corporations and governments. But today corporations have developed tools allowing for the searching and aggregating of any descriptions and recounts of our dreams left online. This actually isn’t a new endeavor to penetrate our dreams. In the 1920s, when Freud’s psychoanalysis was weaponized as a novel technique to better understand colonial subjects, anthropologist Charles Gabriel Seligman, who was a longtime adviser to colonial governments, built a database of colonial dreams within the diverse cultures under British rule. And in 1931 he used a BBC radio broadcast to solicit dreams and auto-interpretations from ordinary people in Britain. In 1945, in Jamaica, a study sponsored by the Colonial Office amassed dream reports and Rorschach inkblot test results from adults and children. Other examples of dream surveillance took place in many countries of the Soviet Bloc.

In 1949, Chris Marker and Alain Resnais did probably the first project based on crowdsourcing to TV audiences, in which they asked viewers to submit their dreams. The most interesting ones were staged and filmed by the two authors in a series of TV programs named Key to Dreams. Soon French TV considered the project too controversial and it was taken down.

My project Cyber Key to Dreams is a collaboration with computer engineers and researchers: Adam Haar Horowitz, Pat Pataranutaporn, and Eyal Perry from the MIT Media Lab and MIT Dream Lab. We built a system which allows for the crowdsourcing of dream reports and a dream questionnaire. We employ a combination of several AI “text to image” algorithms, in order te generate sequences of dream images. The next step is to create aggregated, collective dream images on the bases of the recurring patterns, figures, objects, such as the ghosts appearing in thousands of COVID dreams.

I propose to use AI machine learning to look for recurring patterns in our dreams, in our collective unconscious. In a way I am treating an entire society as one psychoanalytic patient. Perhaps the identification of these patterns can help find ways to heal the collective subjectivity.

Freud talked about the phenomenon of condensation happening in our dreams, which consists of our unconscious fusing together many people we meet in our conscious life into one nonexistent person, or fusing many objects into one condensed object. A similar process happens with machine learning, which produces nonexistent cats, dogs, or human faces on the bases of millions of actual cats, dogs, or humans. In that sense the black box of the AI to some degree resembles the black box of our unconscious.