Today, Mother died. Or, maybe, yesterday; I can’t be sure.

— The Stranger, Albert Camus

I’m not always sure what I like, but I’m absolutely positive about what I don’t. What I know that I know I despise is indifference to the unknown world and its people, especially the things we’ve gotten used to not understanding. Which, by simple inversion, means I adore active responsiveness to foreigners and the foreign: the strange, far off, queer, alien, novel, peculiar, the indecipherable. Time permitting, we can get used to anything. “Foreigners Everywhere” declares the title for the 60th Venice Biennale, curated by Adriano Pedrosa, welcoming one and all to take cramped Jetstar flights from all over the world to bask as one in reverence of inclusion, decolonization, and the reversal of Otherness. (All these lovely, orange air flights while proclaiming their goal of achieving “carbon neutrality” certification. Green cards sell, but that’s another story.) The feminist collective Claire Fontaine was the inspiration for this year’s title, with their neon sculptural works of the same name that commenced in 2004. The phrase comes, in turn, from the name of a Turin collective that fought racism and xenophobia in Italy in the early 2000s. Claire Fontaine’s 2017 deontological open letter always struck a low-key Kantian chord:

Since the very beginning of Claire Fontaine, we have always stated that there is no “good” context to exhibit artworks because everywhere is somehow colonized by commodity. Nevertheless, we believe that claiming a space and using it in an inappropriate and liberating way makes a difference, and that’s why we have made and continue making exhibitions. We believe in the missing people, we think they can materialize at any moment and that you might be one of them. We know that the stranger, the passer-by, will give meaning to our artworks through the grace of his or her curiosity and openness, creating the space where things become possible. Your emotional and political intelligence are the world that we can share.

Everything else is solitude.

Every human, I suspect, deep down, has the urge to understand others and create better worlds that include everyone, including foreigners. This dutiful endeavor was taken up by Pakui Hardware with their “Hope Station,” as writer Valentinas Klimašauskas accurately baptized it. Scripting the human and porous traces of a modifying future is a dietic intervention Pakui Hardware backs like a surgeon, showing up, mind sterilized, taking up plenty of operating room in the Lithuanian Pavilion with their kinetic, phenotypic socio-artistic changes. For a change, I’m certain I like it. Engorged, chafing creative cells take over the space by our quick-moving dramaturgical creatures and artist Marija Teresė Rožanskaitė, who signify life by highlighting what we assume is its insufferable antithetical opponent: inflammation. Injuring all and injuring well, defiling life with what we can hardly withstand, handling difficulties of the death drive that propels us, pathogens and irritants respond to environmental conditions: food, air, microbes, amputation, myelin. Moving around the space (literally), looking methodically for new pathways in the landscape, are sculptures born of fire themselves: glass and aluminum walk out of hellish flames, untouched. Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego genuflect before the kinetic sculptures all the way from the Hellenistic period, as Pakui Hardware maps the human nervous system — fragmented, dissolving, epigenetic histories passed down from generation to generation. Utopia is not a myth! proclaims Pakui Hardware. But isn’t it?

I took a break after the show because my knees and self-esteem hurt watching all the young artists and press teams looking better than me. One of my several hundred bosses, Juju, sipped her Negroni and jasmine and said to me, or slurred rather, that I was a bit peculiar — I couldn’t really mind if it were a fact. It wasn’t a disaster. She asked me what I thought of Pakui Hardware’s exhibition and said we should compare notes and propositions and maybe order another flower Negroni before using our knees again. I read back on my notes, smeared in jasmine and hibiscus stamen: Everybody, everybody has the right to a better world, yet how do we deal with the memory of strangers who’ve invaded, made people missing, and whose land is colonized when everybody is looking?

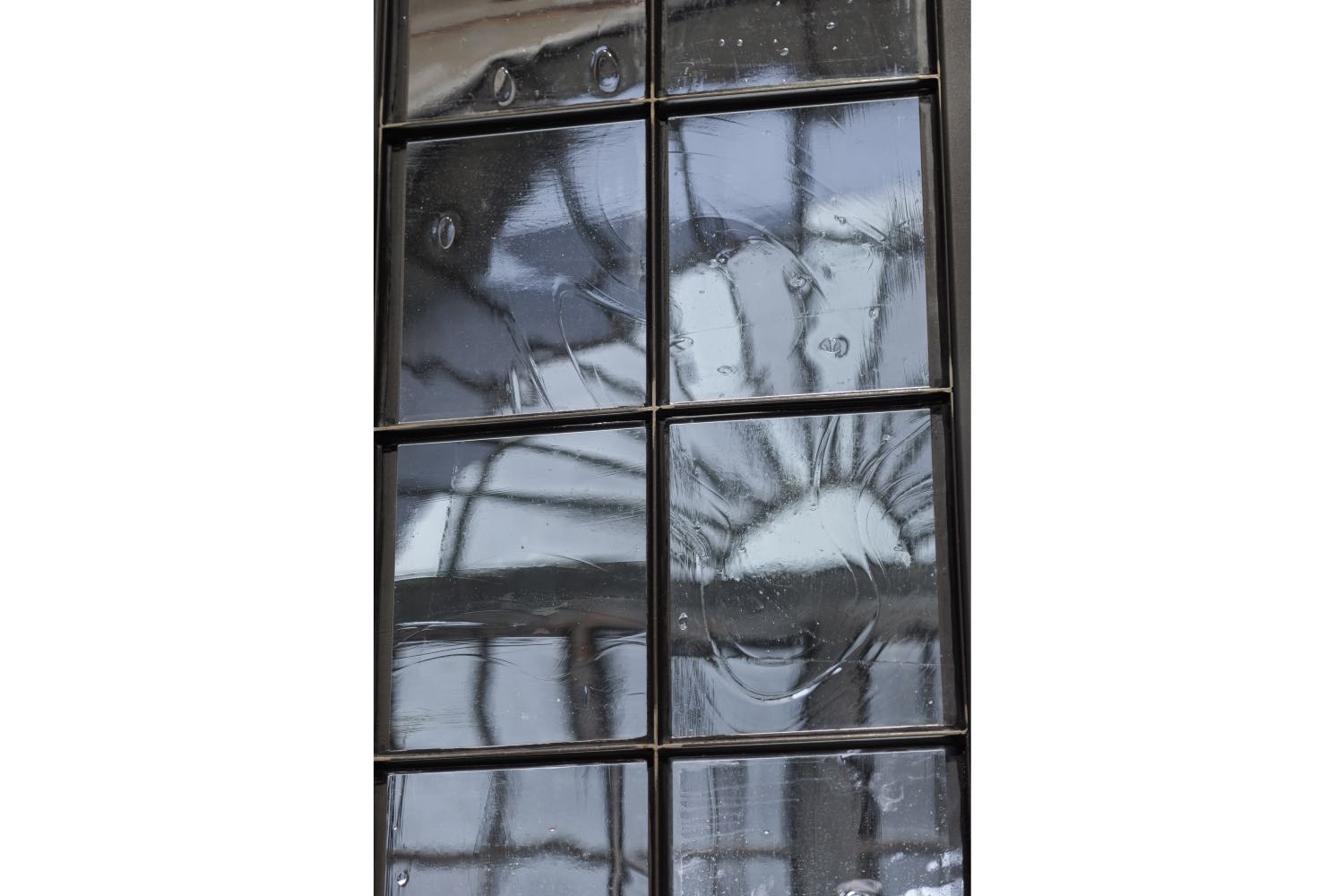

Reminding us that past stories can be a far cry from utopia with three quick knocks at the door of misty recollection is Chloé Quenum’s contribution to the Benin Pavilion’s “Everything Precious Is Fragile.” Quenum is not upfront in her aesthetic pursuit of highlighting what has stayed in the shadows; hers is a subtle, blown-glass arched bay window made with craftsmen from Murano, replicating, to scale, the pavilion’s architecture, hovering above the ground like an otherworldly miracle — a gorgeous phantasm floating, diaphanous, and stroked by sunlight that took eight whole minutes to reach Earth. You can walk the entire way around the sculpture, observing glints of tardy light through the glass at different times of day in disparate ways: a psycho-physical apparatus with ethereal beauty is subject, always, to extreme solicitation. Memorization of the original architecture depends on the mind’s capacity, or willingness, to store information of the memory of places and relations forming from the continuity of an experience. What happens when the memory of a home, objects, culture, and its people is compressed behind disgraceful colonial shadows before having the chance to hold ground within present information? We cannot fault a place for barely having a chance to develop coherent opinions of itself. You see, the depth of memory is reduced; thus, the perception of a transparent historical past and existential diachrony tends to disappear. This is particularly true of countries, cultures, and artistic artifacts that have undergone the opaque process of colonialism, as is the experience of Benin, which the French colonized in the nineteenth century. This is no good. The effect is predictable, so Quenum, in incommensurable sass, elevates the roots and transmission of musical identities, fainted verity, and instruments from the Kingdom of Dahomey — present-day Benin — forcibly dimmed by French settlers. Presented around the exquisite archway from every side are artisanal glass reproductions of traditional Dahomey instruments, particularly those played by women during wars and parades: shekeres, iron bells, drums in tightly stretched beauty, whistles calling in dusk. A country’s history and cultural identity are primarily connected to what we’ve allowed to settle in personal memory. Without translucent information, we can dynamically hypothesize that we’ll move toward a progressive disidentification, where the music and sounds of war leave no imprint. What instruments of analysis and evaluation criteria allow us to speak of a people’s artistic sensibility, music, enjoyment, and suffering? Quenum’s levitating notes of instrumental glass, which cast as much shadow as they do light, offer an aesthetic rebuttal: we have no other instrument but ourselves, our antenna, our bodies, our hearts, our unrushed sensibilities, our cultural reactivity. How quiet the moments when a struggle can only lead to triumph.

Still slurring words with thickened tongue, moaning about slow-boat connections on the canal, Juju grabbed my hand, leading the way to the next exhibition, which disgusted me; I hate people touching me, but she was my superior, so I hadn’t much choice. The COSRX Snail Mucin essence she’d put on her hands at the table was rubbing off on mine, which cheered me up. Snail Mucin is hella expensive 96% of the time. My knees were propped by an espresso martini I’d sucked up after the Negroni with a glass straw to save the environment and get that green card. But that’s another story.

International Art Venice Biennale. Photography by Ugnius Gelguda. Courtesy of the artists,

Lithuanian National Mu

seum of Art and carlier | gebauer, Berlin, Madrid.

The Swiss Pavilion must have known my slinky superior and I were coming, half-disgusted, quarter-drunk, our shimmering snail trail bleeding behind us like a phosphorescent art-world cape. Guerreiro do Divino Amor’s “Super Superior Civilizations” cranked up the postcolonial distortion in baroque-like tics, birthing an enormous colosseum. According to the artist, architecture is an anthropologically constituted — and hence insuperable — character of alienation. He regards the variations of superiority and alienation as being identifiable through classical cartographic views of urban space, which he demonstrates through a reconstruction of the “superior” materials of antiquity — an installation of phallic Roman columns, Fellini fountains, marble in its pricey, inexorable magnificence. His film The Miracle of Helvetia (2022), nestled within this opulence, births a paradisiacal Switzerland that might just force the abolition of political superiority and capitalist social relations by purporting a balance that clearly doesn’t exist: harmony between nature/tech, capitalism/democracy, elegance/brutishness, self-determination/colonialism. He believes balance is the path to deliverance from our evils. Reliant on this illusion, he weaponizes Utopia with a kempt, sarcastic guffaw at all the white, chauvinistic, xenophobic, authoritarian theories we simply must dismantle. It’s a crucial report. The artist continues his tongue-in-cheek finger point with Roma Talismano (2024), engaging three live performers with a desire for real calls to liberated balance vis-à-vis the songs of allegorical animals: a she-wolf with ears of gold, a bronzed gladiator-eagle, and a haloed lamb. She-wolf is the universal mother to the Superior; the eagle symbolizes Roman war supremacy; the lamb is the susceptible manifestation of purity and innocence — an amusing topography of socially constructed mythological hierarchy. Nonetheless, balance plays a crucial role in his philosophy because, as a concept, it serves as an experiment in humor: oh, to laugh at our pathetic, delusional selves, overloaded by our grandiose self-importance! Rather than blithely accepting teleological views of politics, he pokes fun at white supremacy, false identities, inequity, and cliché through mythological hyperbole and, perhaps ultimately, the unresolvedness of balance. A superficial world atlas that, with any luck, spawns the collapse of humankind as we know it.

For the first time in a long time, I remembered you needed exaggerated notions to highlight things that people know nothing about, or if not nothing, not enough, not even nearly. Perhaps ANGA (Art Not Genocide Alliance — a collective of artists and cultural workers) was remembering that very same notion when claiming space outside Israel’s Pavilion, urging a total boycott in light of the xenophobic unfoldings taking place in Gaza at the hands of the Israeli Defense Force. Israel’s “closed” pavilion shows Ruth Patir’s work clearly through the front windows. On opening weekend, Patir appeared to be giving a tour of the “closed” pavilion to right-wing Italian culture minister Gennaro Sangiuliano. Optics are everything. On the morning of April 17, using their emotional and political intelligence, ANGA demanded a world that we can safely share: strangers and non-strangers alike. Isn’t that the shared world Claire Fontaine purported? ANGA developed its own imploring letter with over twenty-four thousand signatories addressed to the Venice Biennale, asking them to completely remove Israel’s national participation, a precedent set when they liquefied South Africa’s involvement during apartheid. However, the Venice Biennale refused their “malapropos” appeal.

ANGA stands in solidarity with all who have been silenced, censored, disciplined, dismissed, and intimidated for speaking truth to power. For demanding ceasefire now. For condemning genocide. For signing open letters. For expecting accountability. For participating in boycotts. For withdrawing their work and labor. For believing in equality and justice. For saying Free Palestine.

Claire Fontaine signed the open letter.

So did Neringa Černiauskaité from Pakui Hardware.

So did Guerreiro do Divino Amor.

So did I.

The artistic pursuit of inclusion, decolonization, and reversal of Otherness shatters harmony on the day, the exceptional un-silence that must take place to draw attention to strangers lodged with bullets, motionless, or left without a trace. “Today Mother died. Or, maybe, yesterday; I can’t be sure,” starts Albert Camus in The Stranger (1942), unsure of time, uncertain in his dizzying, hellish world filled with loss and torrid grief. Words that could just as easily be those of a disoriented Palestinian child, eyes wide and licked with ash, indefinite about the death of their mama suffocated or suffocating under the grit and rubble of their beautiful wasteland. Israel’s “Fertility Pavilion” vulgarly fails to consider, let alone address, all the pregnant, amputated, dead, infected, or injured Gazan mothers who, at this moment in history, are anything but glowing in fertility. Certainly not the four thousand mothers-to-hopefully-be whose embryos were decimated at Al Basma IVF clinic while writing this dispatch. It’s an absence hardly missed.

When we knock on the door of art, the Cherenkov glow of the Venice Biennale, we’re reminded of all the foreigners, the indigenous everywhere, who’ve been collateral damage in the pursuit of land, power, money, or ideology. Art can democratize, but importantly, artist-visitors — themselves foreigners — have the right to pursue political democratization, to defend Others’ self-determination, to cry out over humans that are collateral damage, claim space using “inappropriate” methods that hope to, and will, make a difference, together.

Everything else is solitude.