The 2006 Taipei Biennial, titled “Dirty Yoga,” opened in early November at the Taipei Fine Arts Museum. The Taipei Biennial began in 1998 and helped to establish the region’s biennials — one third of the world’s biennials take place in the Asia Pacific — making Taipei stand out from its prestige and international scope.

The 2006 Taipei Biennial, titled “Dirty Yoga,” opened in early November at the Taipei Fine Arts Museum. The Taipei Biennial began in 1998 and helped to establish the region’s biennials — one third of the world’s biennials take place in the Asia Pacific — making Taipei stand out from its prestige and international scope.

In 2000, the Taipei Fine Arts Museum initiated a new procedure for selecting a well-known Western curator along with a Taiwanese one. This year Dan Cameron paired up with artist Wang Junjieh to curate the fifth edition of this biennial. They brought together 36 artists from around the world with a high percentage of women as well as artists from typically under-represented countries.

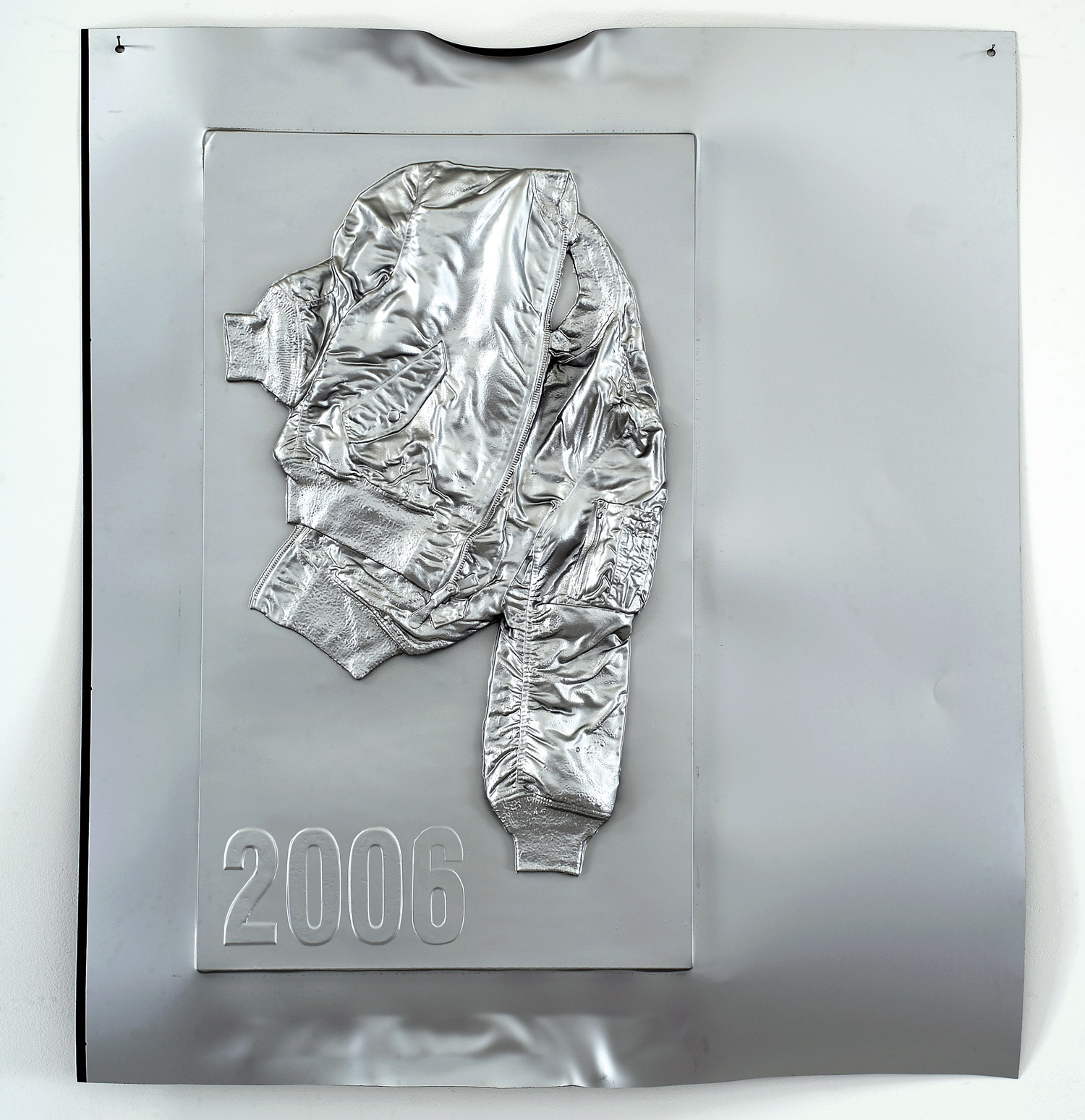

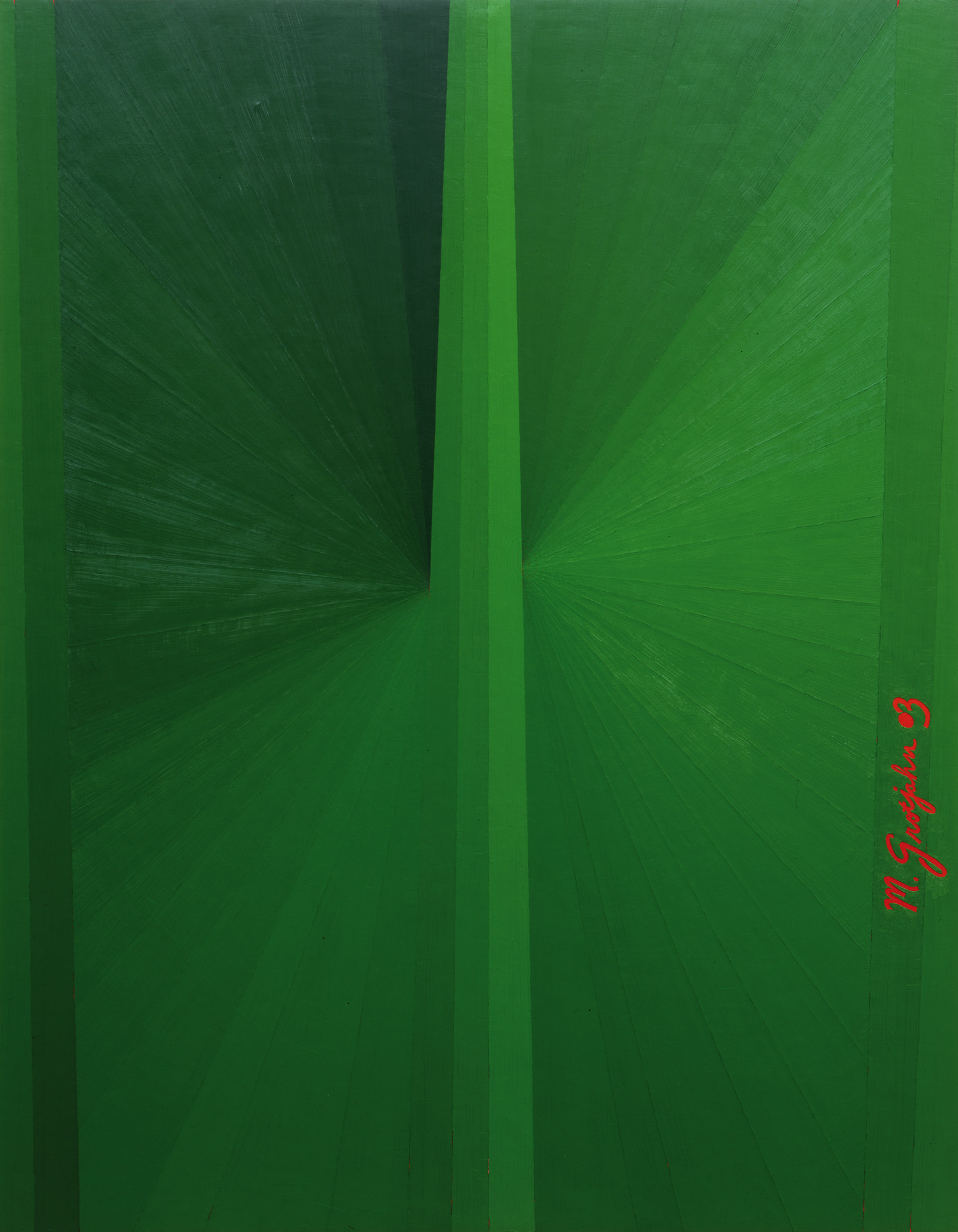

Beginning with the theme of “between-ness” to examine the intricacies and simplifications of the globalized world, they chose artists whose work promotes a ‘third way,’ a synthesizing view of the world rather than a ‘black-and-white’ dichotomous one. Combining two words in the title, “Dirty Yoga” alludes to the glamorous and consumerist way yoga is marketed in Taipei, while the desire for a fit body masks the inevitable decay and loss we all face.

Despite the budgetary limits, the provocative videos, photos, paintings, sounds and sculptures showed that a biennial does not need deep pockets. Simple in design with a clean aesthetic and an overall formalist presentation, there is nothing dirty about this exhibition; mainly white walls with rectangular framed works with a painterly sensibility in arrangement and presentation helps to make the exhibition more accessible to the public.

Some works provided dystopian views of our current state: Alexandre Arrechea’s sinister sculptural tree of surveillance cameras, Jonas Dahlberg’s ominously entropic Invisible Cities, Lee Bul’s imaginary post-apocalyptic landscape and E Chen’s unraveling yarn installation. Other works held out hope for the future: Shu Lea Cheang’s TAKE 2030 that offers an accessible wireless world, Emily Jacir’s Palestine! Free Palestine! that documents an Israeli Day parade in New York and Carolee Schneemann’s montages of war and violence.

The absurdity of the human spirit was seen in Nari Ward’s Black Top Man, Araya Rasdjarmrearnsook’s videos of institutionalized women and Francesco Vezzoli’s self-parody of the cult of celebrity. Deeply probing works included Kazuna Taguchi’s uncanny digital composites of women and Nalini Malani’s Mother India, a riveting five-channel video installation that examines the extreme violence against thousands of women during the birth of the nation.

One of the most relevant works was Cao Fei’s touching paean to the paternal figure, an installation where her father, a notable sculptor, displays his bronze sculptures of Sun Yat-sen, the “father of modern China,” revered on both sides of the tense Taiwan Strait.

Despite undertones of pessimism and war, solipsism and solitariness, a positive message does emerge: art can provide us not with answers but with ways to understand what drives us.