A sense of audio-visual immersion welcomes visitors at the threshold of “Il Nostro Tempo, CinéFondationCartier” at Triennale Milano, ushering them into a unique cinematic experience. Within this journey, one can pause or linger on Tacchini’s velvet sofas and armchairs, while eleven cinematographic works by artists and directors from different generations and backgrounds unfold in a carefully curated landscape, masterfully designed by bunker arc studio. This spatial arrangement – featuring corridors, black curtains, open areas, and custom-made rooms – creates an intimate setting for experiencing each film individually: an approach that confirms and reinforces Fondation Cartier’s three-decade-long commitment to exploring the relationship between moving images and exhibition spaces while supporting film production.

Curated by Chiara Agradi, “Il Nostro Tempo” presents both short films and long-form works, some making their Italian debut. As the title suggests, in its broad openness to interpretation, the selection reflects on the contradictions, vulnerabilities, transformations, and urgencies of our time, explored through diverse artistic sensibilities. Some films come from Fondation Cartier’s collection, while others were previously showcased in its programs. These movies delve into themes of technology, memory, nature, life, war, history, and politics, circling around a central yet unanswered question: What defines our time? Without claiming to find a single path toward possible answers, the films tend to follow sprawling routes to fertile ground. The result is not unidirectional; rather, it resembles a mosaic where universes, visual languages, and voices merge and intertwine into an overwritable map.

“Il Nostro Tempo” opens with Au bonheur des maths (2011), a black-and-white work by French artists Raymond Depardon and Claudine Nougaret. Featuring a group of nine renowned mathematicians (including Misha Gromov and Cédric Villani) recounting their enchantment and passion for scientific thought, the thirty-three-minute film lyrically highlights how formulas and numbers are “correspondences and correlations” that function like “overlapping imaginary worlds.” It couldn’t have been a more fitting start to unravelling the complexity of our existence.

These fleeting portraits give way to the alienating, exhausting, fifteen-hour-a-day labor of 300,000 young migrant workers. Shot in a Chinese garment factory, Wang Bing’s 15 Hours (2017) offers a solitary, brutal immersion into the paradoxes of modern China’s progress. In contrast, French director Jonathan Vinel extends this profound sense of loneliness, anger, and alienation through a different aesthetic. In Martin Pleure (2017), using sequences from the video game Grand Theft Auto V, the protagonist suddenly loses his friends and searches for them in vain. Vinel’s post-apocalyptic world is a desolate landscape, eerily reminiscent of our own. Yet, amid the violence and fear, traces of love endure. Similarly, Decades Apart (2017), a short film with a 3D video installation by South Korean duo PARKing CHANce, blurs the line between reality and fiction. The film recounts the story of dictatorship by providing a totalizing and riveting experience based on Joint Security Area, a film directed by Park Chan-wook in 2000, whose title alludes to the name of the demilitarized zone dividing North from South Korea.

Both Eryk Rocha and Gabriela Carneiro da Cunha’s A Queda do Céu (2024) and Morzaniel Ɨramari’s Mãri Hi: The Tree of Dream (2023) intimately address the life and culture of the Yanomami community, one of more than three hundred indigenous populations in Brazil, numbering nearly thirty thousand individuals across the vast Amazon rainforest. In Mãri Hi: The Tree of Dream, Ɨramari delves into the Yanomami’s spiritual world and oneiric experiences, offering an inclusive perspective on their conceptual and cosmological imagination. Rocha and Carneiro da Cunha’s work portrays the cosmo-ecological thinking of the Yanomami people — whose existence is threatened by geopolitics — and their struggle to protect their lives. Shifting to Paraguay, El Aroma del viento (2019), a Super 8 film by Paz Encina, takes us into the heart of the country’s native trees, which the writer and director recalls through some personal archival footage from her childhood. Like A Queda do Céu, El Aroma del viento evokes the struggle to safeguard and conserve the forest and its memory.

Perhaps the most striking works in terms of lyrical presence are Notre Siècle (1982) and Vie (1993) by visionary Armenian director Artavazd Pelechian. Presented inside a futuristic bubble of wood and canvas, Notre Siècle reflects on the major innovations that shaped the past century, condensed in a whirlwind montage of images and archival footage dedicated to technological and scientific progress, but also to accidents, crashes, and failures. In contrast, Vie – a visual poem that closes the exhibition – offers a poignant celebration of life. Projected on a small monitor suspended from the ceiling in a dark, unadorned space, this piece lingers in the memory like an apparition within a universe that never ceases to surprise us: the miracle of birth. Another film draws on a montage of archival images, again playing with the topic of dictatorship. Andrei Ujica’s The Autobiography of Nicolae Ceausescu (2010) submerges the viewer in the power of images, revealing their ability to forge an alternative and contradictory vision of authoritarianism.

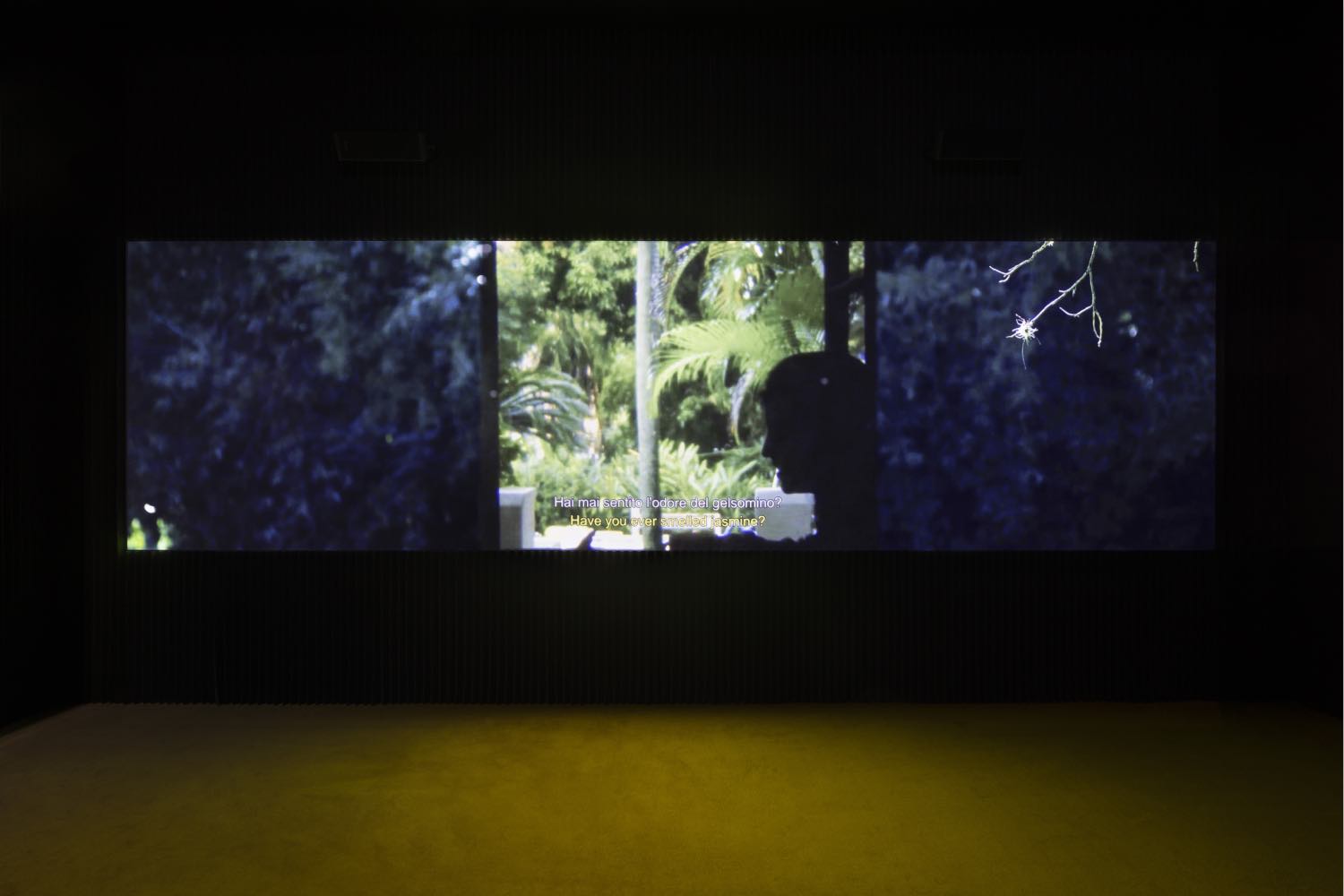

Without an overarching curatorial theme, the works in “Il Nostro Tempo” connect organically in a shared, new perspective to probe our present time, its vacillation, responsibilities, and legacy. They weave together and favor a sensorial approach to cinema in the context of an art exhibition, celebrating the mundane, natural, cultural, and sociopolitical processes that interweave in layers of temporality. The exhibition seems to ask: How can we navigate this? And, even more fundamentally, how can we understand it? We are given no answers, only a series of suggestions that perhaps do not find any form of reassurance, even in the domestic and intimate setting of Le Triptyque de Noirmoutier (2005) by Agnès Varda, a three-channel video tableau inspired by Baroque Flemish paintings. An elderly woman, a young lady, and a middle-aged man are seated quietly around a rustic kitchen table, each engrossed in their own tasks. Its lack of a story, along with our desperate need for it, provides a powerful contrast within the atmosphere of the exhibition.