In the 1952 musical classic Singin’ in the Rain, there’s a moment when Donald O’Connor’s character, Cosmo Brown, tries to cheer up his friend Don Lockwood (Gene Kelly) by launching into the high-energy number “Make ’Em Laugh.” As Cosmo moves through a soundstage filled with discarded set pieces, he transforms the space through physical comedy — bouncing off walls, flipping over furniture, and revealing the artifice of the scenery. A hallway turns out to be a painted flat, a door opens onto a brick wall, and a seemingly solid structure crumbles on impact. It’s a playful reveal of cinematic illusion, a dance between reality and fiction.

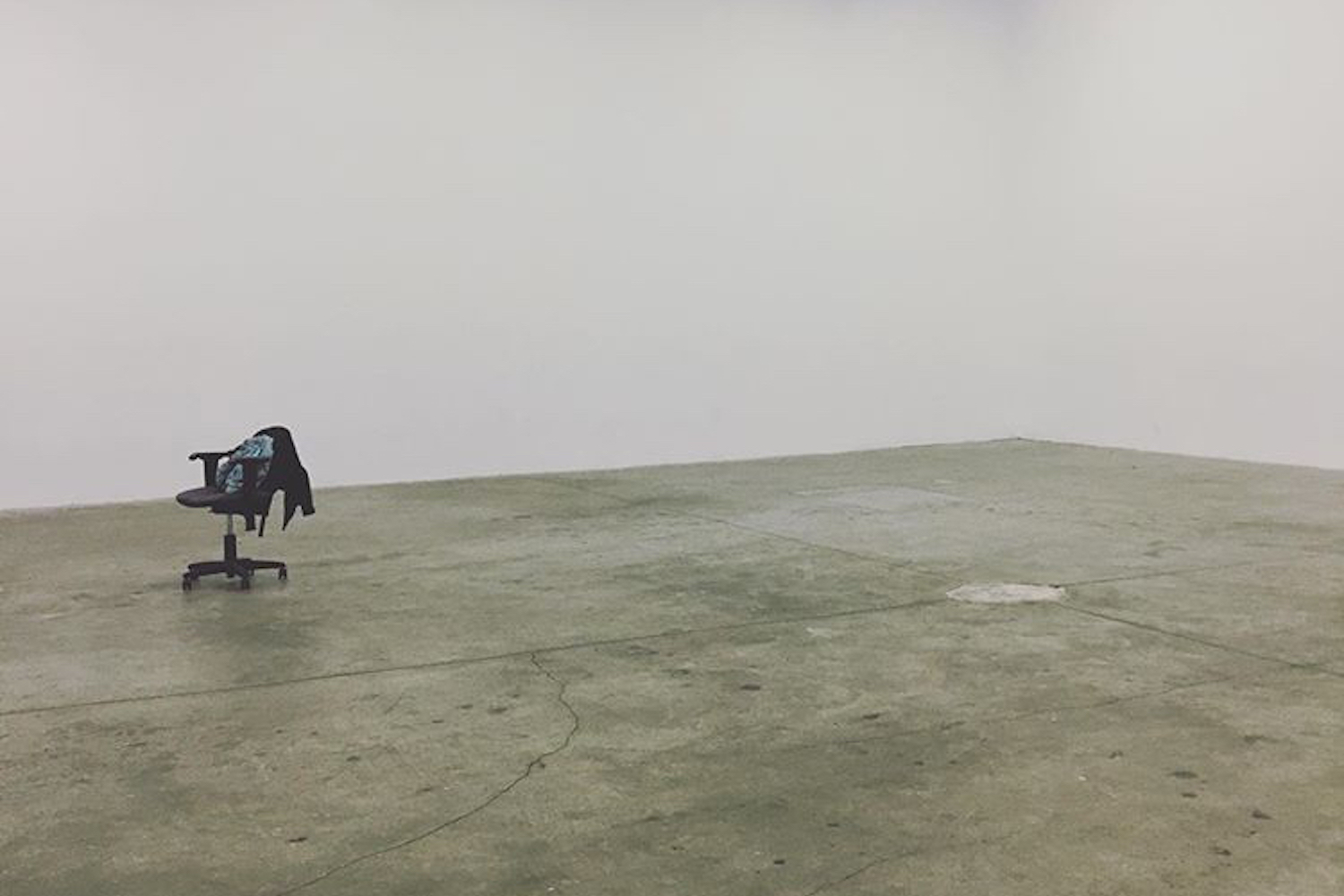

In “Broadcast: Transference,” the New York–based artistic duo Ciccio (Francesco Vizzini and Norman Chernick-Zeitlin, who since 2019 have been producing a series of collaborative exhibitions) has similarly staged a set of sets in the gallery at O-Town House — reviving the discarded plywood walls from Hollywood production warehouses. Once used for sitcoms as ersatz doors, walls, and windows, here the found sets are combined and rearranged as sculptures but remain in their original state. Traces of their former contexts are legible in sharpie scribblings on their sides or in floor plans pasted on their backs. Some walls are punctured with holes, others bear the scars of long neglect in storage, their cheap materials now crumbling. In this state, they exist between past and present, between illusion and disrepair — a collision of fictional histories and lived decay, repositioned by the artists’ intervention.

You assume you have a life (2025), the central work, is a corridor-like structure built from repurposed set walls — some painted, some wallpapered, some mimicking brick in cardboard, one punctuated by a window. It forms a narrow passage in the middle of the gallery, inviting viewers to either walk through it or circumvent it, exposing the raw wood on the outside. The piece offers a choice, though the title suggests an illusion of autonomy. Reminiscent of Bruce Nauman’s Performance Corridor (1969), a narrow hallway made of two parallel wallboards mounted on a wooden frame, Ciccio’s sculpture is less constraining. The piece possesses a whimsy that the minimalist sculpture lacks. For example, a small disco ball rotates inside the hallway; unlike Nauman’s dead-end corridor, viewers can traverse Ciccio’s passageway to the other end, where they are met with a wall of blue sky and cartoony white clouds, mocking some heavenly arrival while suggesting an extended space beyond the gallery. Inhabiting the installation are small globes covered in fragments of pasted-on newspaper strips that form a kind of concrete poetry. Enigmatic excerpts include “Exhilarating High Above Reality” and “Morning asks for permission to pass through our windows.” Three globes gather toward the back wall as if the force of gravity had pushed them there.

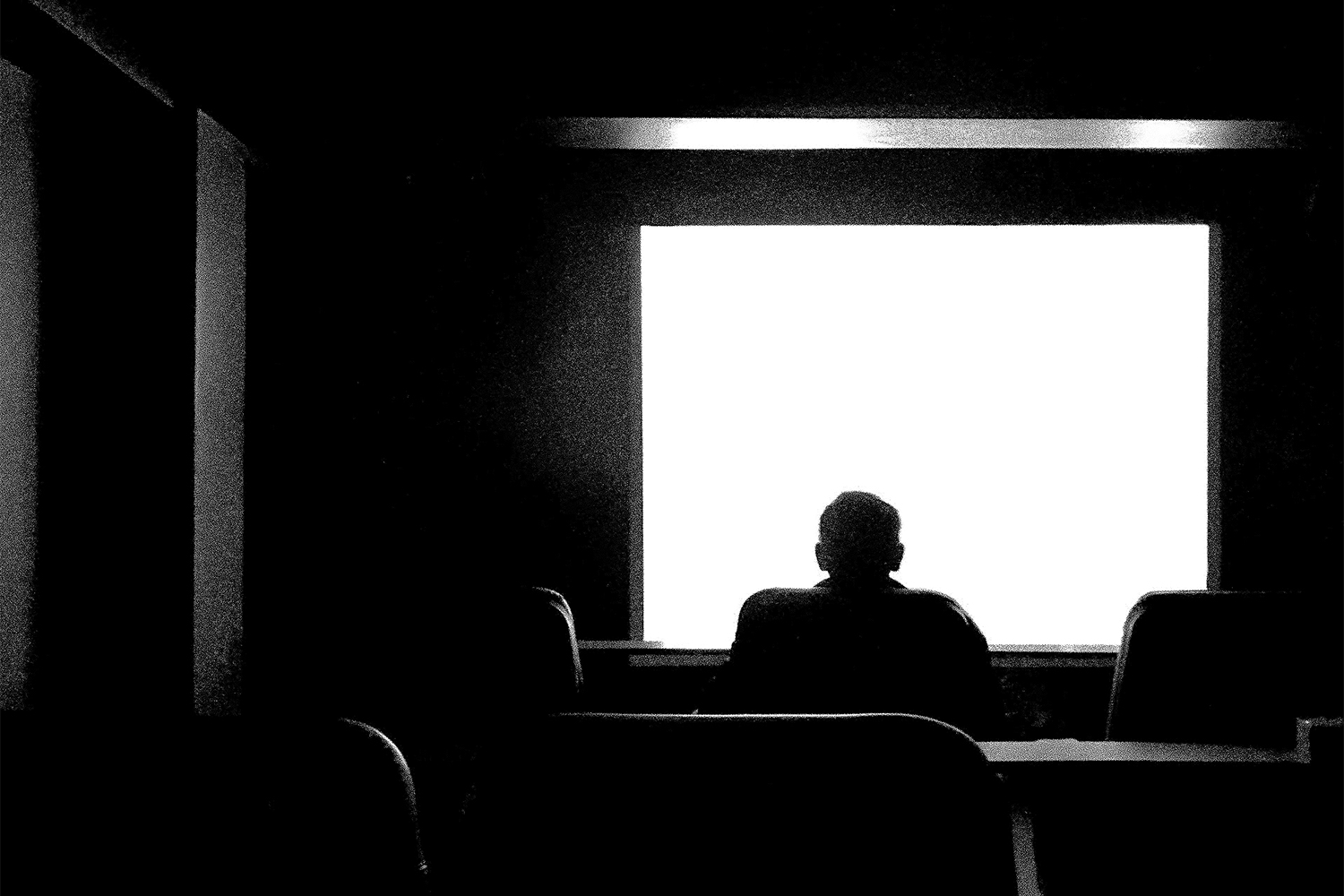

In the exhibition’s accompanying text, Cassandra Seltman expands on the show’s title in psychoanalytic terms. She writes, “Viewer and screen are not a relay of meaning but rather a Möbius circuit where the scene generates the viewer’s desire [and] the viewer’s desire generates the scene.” The exhibition’s promotional image shows the two artists reflected in a laptop screen displaying a still from Bertolucci’s The Conformist, thus merging viewer(s) and scene into one. Ciccio’s work asks the viewer for a similar kind of participation — to dance through a set all the while revealing illusions. Suspended disbelief is something that art often requires and that artists expect. It is this exchange of desire between scene and viewer that keeps the world turning.