This year’s installment of Condo London denotes the project’s seventh edition in its city of origin, with forty-nine international galleries convening in the UK’s capital to partake in the self-styled “collaborative exhibition” hosted across twenty-two spaces. By now, the gallery-sharing initiative begun in 2016 is a fixture and its format is familiar. Likewise, Condo has been absorbed into the contemporary art vernacular, used mostly in slangy shorthand, but also occasionally as a metonym for a particular subset of the London art scene that foregrounds the social over the commercial in art-making.

In 2016, the general perception of Condo as an incubator of young talent — artists and galleries alike — was true of its participants. Vanessa Carlos’s project prominently positioned the sharing of precious gallery square footage as a cost-cutting means to show artists internationally sans booth fees and other fair limitations. In this scheme, work is mounted in the comfort of a fellow gallerist’s space instead of the ever-impotent fair tent (or convention center or local airport: pick your bleak non-place1).

Yet the motivation of this structure — predicated both on cooperation in the pursuit of art and an aversion to its corporatization — puts Condo in a tricky position today. In the time since it was conceived, Carlos/Ishikawa and galleries of the like, including original Condo collaborator Arcadia Missa, have climbed the hierarchical ladder, while others, like Sadie Coles HQ, greengrassi, and Maureen Paley, already comfortably held spots at the top for well over a decade. By the same token, artists on these rosters — Oscar Murillo, Issy Wood, Nicole Eisenman, Laura Owens, Korakrit Arunanondchai, Lisa Yuskavage, and Urs Fischer, to name a few — command blue-chip prices.

Of course, six-figure auction results don’t reflect anything intrinsic about an artist’s work in themselves, and concern with the market is endemic to the art world’s functioning. My point here is that Condo was formed specifically to elude today’s shameless commodification of art. It’s an inevitable progression to succeed commercially when the programming is deliberate. This nevertheless leaves the potential for a growing lacuna between the intention at Condo’s outset and its function at present, posing a risk of the project becoming an exercise in habituation rather than continued critical refinement.

Putting all of this aside, Condo’s qualms about the purely commercial naturally attract artist-forward galleries, meaning the annual set of shows still offers something substantive, even if many involved don’t qualify as emerging or pointedly experimental.

For instance, Hollybush Gardens partnered with New York’s Gordon Robichaux for a two-person exhibition by Janet Olivia Henry and Cynthia Hawkins, who share roots in the 1970s New York community cultivated by Just Above Midtown, the era’s pioneering gallery for Black artists. Each is a developed practitioner in her own right, but what really makes the show so enjoyable is their palpable friendship. The formality of Hawkins’s abstract paintings and works on paper is matched in intensity by Henry’s delightfully cheeky sculptures, which emit something akin to the big wink and sly smile of an intelligent mischief-maker. This dynamic culminates in Henry’s new diorama, Cynthia and Janet at JAM on 57th Street (2024), a reimagining of her 1983 work The Studio Visit that swaps the original’s white “curator” doll for a Black one representing Hawkins. The two met while working at Just Above Midtown, making this new diorama in her series an ode to their friendship that is all the more endearing for its self-aware dash of silliness.

Maureen Paley hosts Air de Paris with a taut exhibition of Wolfgang Tillmans and the late Pati Hill, in what is the gallery’s second consecutive notable Condo presentation following last year’s airtight outing, with Christopher Aque and Alexandre Khondji, brought by Sweetwater, Berlin. Like Hollybush Gardens, this too has a historic bent, pairing a 2011 inkjet print by Tillmans with a synoptic set of Hill’s unique xerographs, dating between 1977 and 1990, mounted opposite. Hill’s work with IBM photocopiers sought to employ the copy machine in “uniting” artists and writers in a visual language, drawing on its purpose of reproducing texts as the basis for her thinking. This shared interest in the photocopier’s capabilities, and in wielding it to express form, traces a visible thread between Hill and Tillmans, tying together the two generations of artists and placing them — almost literally, per the show’s makeup, where the work of each directly faces the other — in dialogue with one another.

In conjunction with Francis Irv of New York, the new(ish) Brunette Coleman has Rachel Fäth and Zazou Roddam in what is a very sparse arrangement of sculptures and wall works. Fäth’s sculptures, taken from a new series called “Lockers” (2024), are weighty, dense things cobbled from discarded steel that sit on the floor — one appearing to sag under its own weight, recalling the hunched posture of a person defeated — and assume their compressed shape, having been modelled according to the dimensions of, as the title implies, storage lockers. While these sinewy jumbles of mass are impressively formidable, it’s unclear as to why the lockers of an unspecified community workspace are the source of inspiration dictating their shape, which feels like an omission. Roddam also appears to be interested in the materiality of things, displaying wall works comprised of salvaged crystal door handles, stacked vertically and encased in plexiglass, along with a mixed-media sculpture atop a plinth. The doorknobs are strangely whimsical in their mismatched, slightly kitschy assemblage in a skinny, clear box adhered to the wall. Equally charming is Desert Rose (2024–25), made from a composite of aluminum fans, stainless steel, and a doorbell transformer and its bell that for some reason brings an accordion to my mind, or, more appropriately given the name, an iron flower in bloom. There’s a distinct sense of care in these amalgamations of previously owned stuff, which gives the impression that these otherwise-discarded bits and bobs are imbued with new life by way of Roddam’s toying with disparate materials.

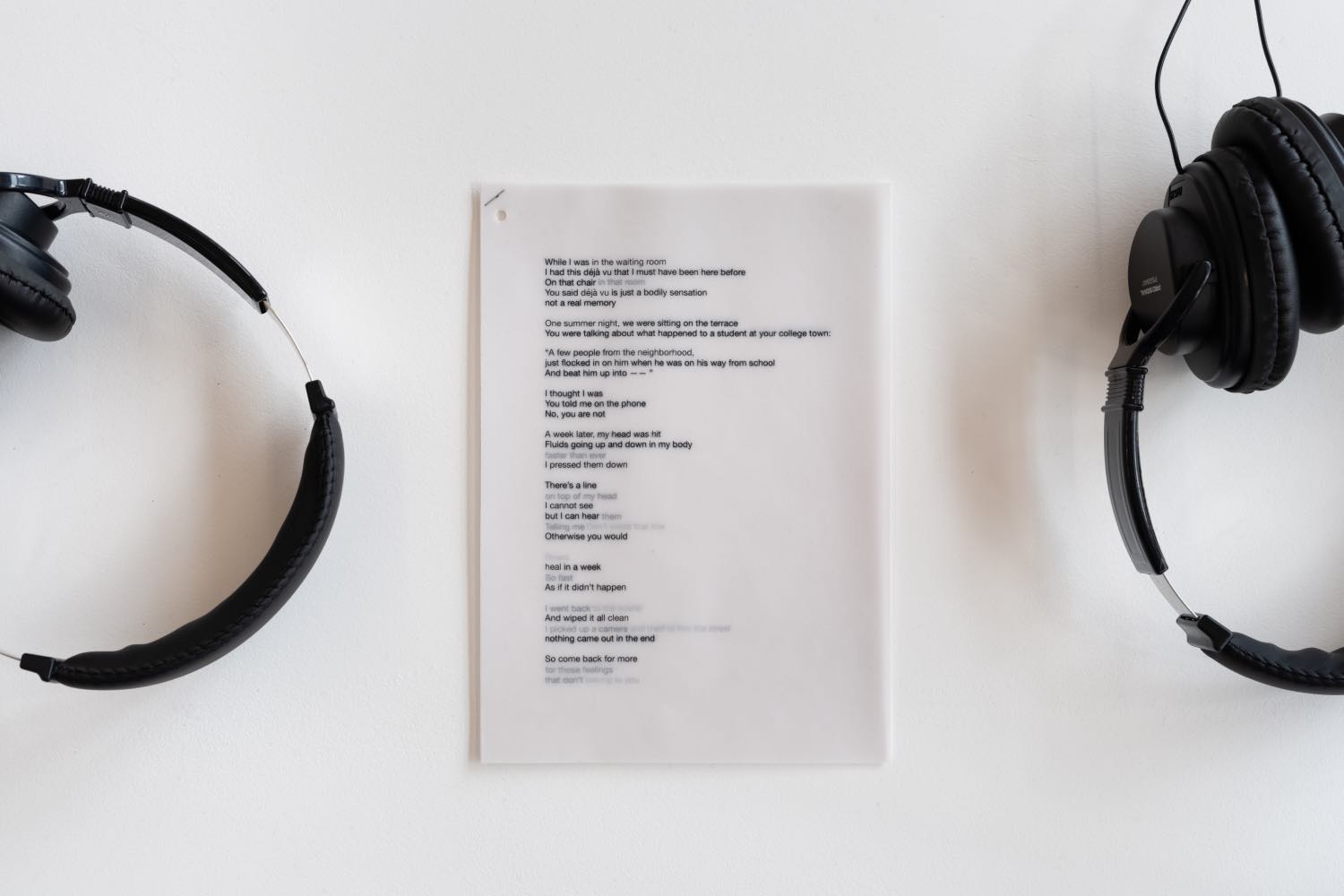

Emalin and its invitee, Shanghai’s Antenna Space, contribute what is by and large an outstanding presentation that would remain so by any metric, regardless of its timing to Condo. In line with the gallery’s often sagacious program, the show is a subdued meditation on affect and subjectivity by Peng Zuqiang and Aslan Goisum, who present two video installations from the former and new series of photographs by the latter. These are installed rather starkly in a clean space that feels notably pristine: a cathedral of straight lines, open spaces, and square placements that sequesters even the audio of Peng’s Deja Vu (2023) to sets of headphones. In hindsight, this makes sense, and feels even complementary to the ambition of this exhibition, in which the atmosphere requires paring down if there’s to be any genuine attunement with its topic of affect. It’s on par with the intimacy of really quieting yourself to listen to the sound of another person’s heartbeat.

It’s easy to confuse subdued with dulled, but it’s the very element of restraint defining its stripped-back aesthetic and staid subject matter — affect being a study in the subtleties of expression and suppression, or varied readings of emotion — that makes this show highly effective in coaxing a state of vulnerability. The two artists maintain individual practices: Peng is generally affiliated with film, video, and installation, and Goisum is roundly slotted into photography. Neither tacitly refutes such labels, but the actual work of both openly flouts rigid demarcations, in the same way it pays vigilant attention to “slippages” in language, histories, and our collective human attempts to understand one another. Peng’s video Deja Vu is a willful and pronounced turn away from commonplace filmmaking, enacted in response to the ubiquitous violence of online imagery in post-COVID China, and made instead with a photogram he chose that negated the need for a traditional camera. So too does Goisum operate in this imprecise medium of image, flattening various photographic processes when producing his images with a methodology analogous to how affect theory is applied to the interpersonal.

Given the current discrepancy between its lofty ideals and faction of galleries, detractors will likely be eager to denounce Condo. In terms of hard logistics, a redeeming factor is that Condo still differentiates itself from the traditional fair by remaining free to the public. (Not to mention that forcing footfall in actual gallery spaces, and not an allocated outpost in a tent or local airport or whatever, would dissuade those less curious or committed to a pilgrimage across the city, as Condo requires.)

I remember a popular Instagram account known for parodying the art world sarcastically — and cynically — posting something along the lines of “I’m a Marxist artist but I also like to sell work,” as if this was a revelatory observation unveiling the hypocrisy of artists, and not more often just the simple, nasty truth about what is required to survive as a human being in any industry under the present monetary framework, regardless of one’s ideology. (I’m also not sure what the point is in mockery: Does the need for money in order to eat and live in a home cease to exist for those who voice opposition to capitalism, or who go into the arts?)

The trajectory of Condo is obviously symptomatic of the art world’s increasing momentum toward complete corporatization. It also continues to stage the event annually, and thus sidestep full-fair indoctrination. In that regard, such a compromise might be read as the opposite of cynicism, in that it stays honest — if not earnest — in certain convictions about the egalitarian cultural value of art.