In “Wooden Travel,” his solo show at Fondazione ICA Milano, Augustas Serapinas continues his exploration of Lithuanian vernacular architecture, this time engaging with a former industrial building and its surroundings. In this conversation, we discuss the balance between destruction and preservation, the hidden political and social dynamics of the space, and how Serapinas’s work continues to evolve beyond the exhibition.

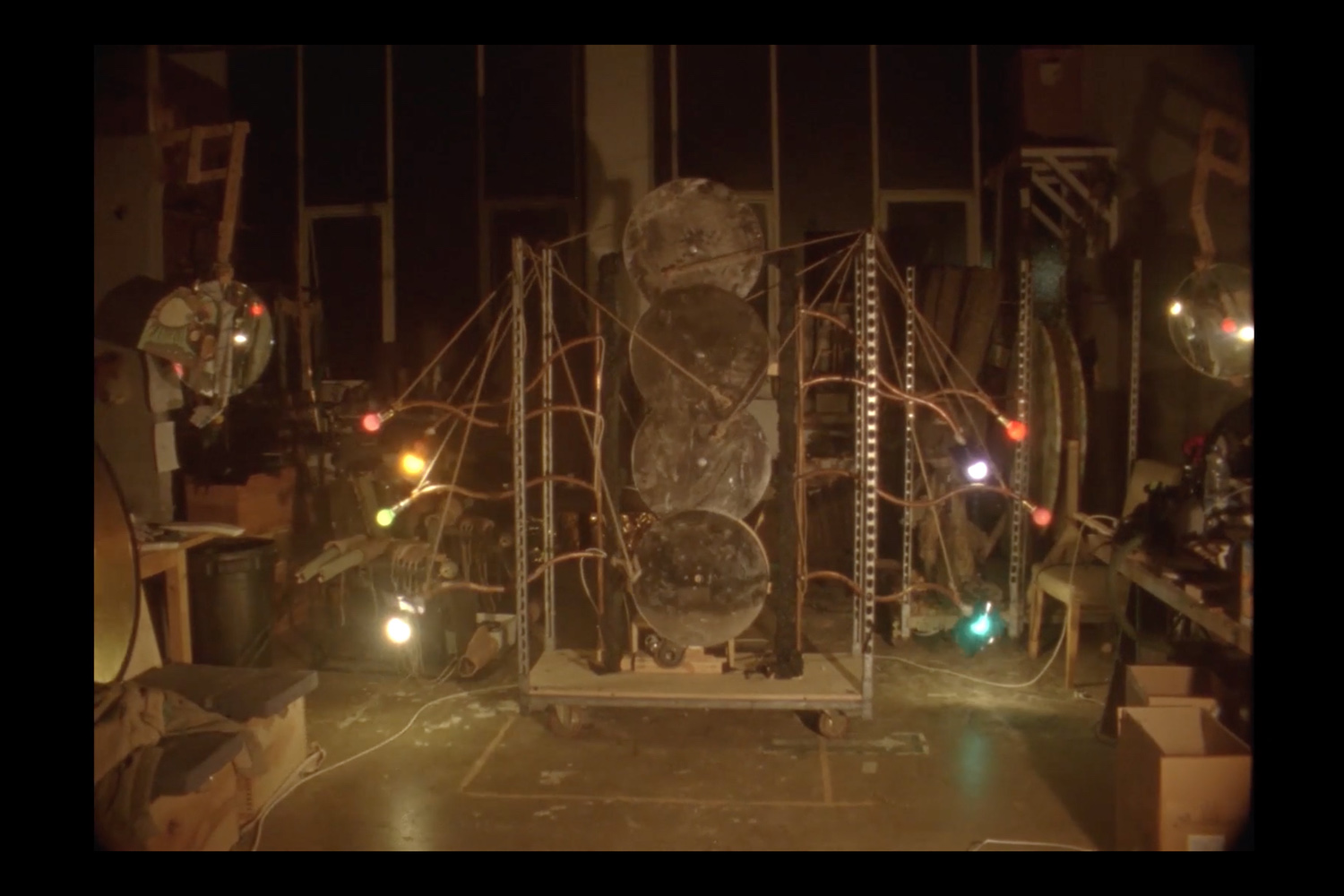

Olesia Shuvarikova: When I entered your show “Wooden Travel” at Fondazione ICA Milano, I noticed the calming scent of wood. The warmth of the material in House of Gaidalaučizna (2024) — an abandoned wooden house located 100 km from Vilnius — stood in contrast to the industrial architecture of the exhibition space. Could you share more about this contrast, the dissonance between Lithuanian vernacular architecture and the industrial space where your work is exhibited?

Augustas Serapinas: I would say it represents two different ways of living. With the Industrial Revolution came electricity, artificial lighting, and structured working hours. Suddenly, daily schedules became framed, and people lost their connection to external factors, which changed the way of life. This is reflected in the industrial setting around us and the exhibition space itself, as it is a former manufactory. The wooden house, on the other hand, represents a way of life more connected to the outside. You would wake up early in the summer with the sunrise, working with the sounds of your surroundings, and in winter you would do more work inside.

OS: The country’s industrial development is an important topic for you, as it contributed to the destruction of wooden houses in Lithuania, I believe?

AS: Most of the wooden houses in Lithuania were built between the First and Second World War. When the country was occupied and became part of the Soviet Union, we stopped building with wood and began using factory-made materials instead. As a result, these houses lost their connection to the rural landscape in terms of materiality. Today, they are disappearing — either demolished or left abandoned to decay and collapse over time. In their place, brick buildings are being constructed instead. In this exhibition setting, I intervene in the industrial environment with a different form of a wooden house. There is no tension between them, but it’s not a dialogue either — more like inception, a foreign body.

OS: How does the history of a place and its surroundings influence your work? Would you say that your pieces reveal architectural, social, or political aspects of a space?

AS: Once you start working with a space or respond to it, you become aware of the connotations of the specific location you’re in. I’ve created a series of works where I looked for the hidden spaces within museums. On the one hand, it’s about hiding within the institution, sometimes literally, and on the other, it’s about revealing what is inside. The space is always open to different possibilities. It’s interesting to think about the function of such a space while considering the surrounding context it is situated in. So yes, I would say my works reveal certain architectural, social, and political aspects of a space.

OS: I remember you broke through a wall on the ground floor of the exhibition space at the Museum of Contemporary Art (M HKA) in Antwerp, in 2014.

AS: Yes, right. It was a very long, narrow shaft, and there was a high platform above that was unreachable for the general public. The only way to reach it was by a staircase, which was only accessible to Georges Uittenhout, the museum’s chief technician. I created a room for him on this platform because he showed me the space, and it was a kind of tribute to him. Coming back to the previous question of the political aspects of space, in my practice, I happen to raise questions rather than point things out directly. Sometimes, you don’t do something for a specific reason; you leave it open on purpose.

OS: By bringing wooden houses from traditional Lithuanian vernacular architecture into the exhibition space, you save them from being destroyed or sold as firewood. You preserve collective memory, heritage, and craftsmanship. However, your work also involves transformation and deconstruction. Could you describe the process of deconstructing the houses and what this transformation means to you?

AS: I think of a wooden house not as a final form, but rather a set of elements. We always think of the house as a very monumental concept, but in the case of wooden vernacular architecture, it can be dismantled, moved, and reassembled into something else. This way, we can look at the building and its parts from a different perspective. I think of destruction as a way of preservation. I maintain the same construction logic, assembling everything without screws and using traditional log interlocks. But I build something else — no longer a house. This way, I reveal the most important idea of such buildings — modularity. When I deconstruct it and show its parts, I think about the essence of this type of architecture. I also work only with houses that are clearly going to be destroyed. It’s like a form of archaeology. However, it is also natural that these buildings disappear; it’s part of the process. The material is sensitive — when the roof starts to leak, it spreads, and eventually, it’s a matter of time before the house collapses. To preserve them, one needs to live in and take care of them.

OS: Talking about care, the black “paintings” Roof of a House from Meškauščizna (2024), displayed on the wall near the installation, are made of burned wood. They evoke a sense of destruction and possibly even violence, potentially alluding to the demolition of homes for new developments. However, the act of burning the wood on the roof — which serves to protect against pests and disinfect — can also be interpreted as an act of care. Would you say that your works often combine a sense of danger and vulnerability with care?

AS: There was a time when you could easily clear land of these buildings because there were no laws protecting them. There was a kind of “gap” in the law where you could say, “it burned by itself,” freeing the land from a house for developers. The wooden roof is the easiest thing that would burn, as it is made from wooden shingles, the thinnest part of the building — once the roof is on fire, it’s difficult to save the house. However, I think if destruction is controlled, it can become a tool for creation. If you control the burning process and apply it gradually it can serve as a good treatment, helping better preserve the material. I apply this method to the shingled roof, balancing destruction and preservation. The process requires very careful control – once you set it on fire, you can’t burn too much, as parts may collapse or be completely destroyed.

OS: In this specific installation, for the first time, you are presenting decorative elements — carvings that are typically found on houses of wealthier landowners, whose homes are preserved in museums, rather than the more common rural houses. Are you pointing here to the question of what is deemed worthy of being remembered and what is overlooked or left out?

AS: I think it’s a very important gesture to have outdoor museums, but the problem with them is that they mostly collect the most unique and “beautiful” examples, which leads to the misrepresentation of the people traditionally associated with these wooden houses in rural landscapes. There’s clearly a mismatch. I was thinking about it when incorporating these ornaments, but they are also present on most houses, just in smaller quantities, and remain an important part of Lithuanian wooden vernacular architecture, deeply embedded in our tradition. My installation is more about the notion and the beauty of the wooden house in general without any implications on the status of its inhabitants.

OS: What happens to your works after the exhibition? Do you dismantle their parts and reuse them for future sculptures, and allow them to acquire new meanings, or do you preserve the works as they are?

AS: I reuse the parts in different ways. Sometimes I build new structures out of it, like I will do with this installation at the exhibition. Recently, I burned one completely down and collected the ashes, from which I made two things. I passed water through it to extract lye, which can be used to make soap. From the remaining ash, I produce ash cement. In the end, I have two new products: soap and cement made from the wooden house.

OS: My final question is about the people you work with — I’ve read that you often involve others in the creation process of your pieces. Could you share more about this curiosity in people and how empathy shapes your practice?

AS: Last year, I spent more time working in the studio in Lithuania, where I did most of my production. I encounter more people when creating site-specific projects on exhibition sites. I would say that empathy doesn’t really shape my work, but perhaps sensitivity does. If you get a good connection, you can gain very interesting insights into a specific context. In the case of Georges at the M HKA, I was interested in the fact that he has been working at the museum for twenty years, yet the general audience was completely unaware of him. So, I would say the words “curiosity” or “sensitivity” are more relevant in my practice.