An artist and analytical philosopher, Adrian Piper pioneered a mode of first-generation conceptual art distinguished by politically situated subjects that raise questions related to the delineations of identity-related experience. Critically examining the limitations of the self as it interacts with and challenges external power structures, Piper has engaged her own physical and mental entity as subject, receptacle, and participant of the work — respectively in public and private, familiar and foreign spaces, and so forth — positioning it within the intersections of race, gender, sexuality, and class. Interrogating the sociocultural complexes of art and its exterior circonscriptions, the work has continuously explored the inflection points between discourse and our participation within it: locating the viewer in an indexical relation to the work, and prompting reflections on spectatorial reception, subjecthood, and agency.

The two site-specific works presented by Piper in “Who, Me?,” the artist’s exhibition at Portikus in Frankfurt, construct an exploration of subjective experiences in the conception and reception of situated language. Upon entering the space, after passing through the museum’s entrance, viewers find themselves blocked by a wall. This wall obstructs both the view and access to the work. To confirm the presence of a work, the viewer must ascend a staircase, reaching a mezzanine that is four meters higher. There, I’m the Tree (2024), a dead linden tree, is suspended horizontally, held by steel wires positioned at four respective anchor points. Its roots, sprawling from beneath, confront the viewer. Emphasized is a sense of gravity — both that of the entire space and of the dead tree — in relation to a situation deliberately established as a temporal suspension (gravitating for a defined moment, to quote the artist’s performative index), with each of its surfaces left intact, offering the viewer a full and detailed view of its trunk, branches, and roots. As such, the tree — undisturbed — resists its condition of death (transcendence, as an effect, is consistently attained in Piper’s work), remaining whole, still, and only visible from the corridors of the mezzanine that surround it as a peripheral pathway. Below it, mirrors have been placed on the floor, reflecting all forms inaccessible to the gaze of the spectator positioned above, thus providing unilateral access to the tree both in its immediacy and reproductive reflection.

In a text written in 1982 on the unrealized work Slave to Art, Pipers reflects on the idea of utilizing her own body as an object (in this context, an object of art) within a cultural and political power structure (the museum) in exchange for “protection, security, maintenance, and public recognition for at least two and no longer than three weeks.”1

During this period, an individual designated as a symbol of institutional and artistic power (Pontus Hulten) would have had the freedom to “use my talents and resources in whatever way he or she sees fit […] nude, with a collar around my neck chaining me to my pedestal (of course, there’s a pedestal), surrounded by four male guards roping off the area.” By asserting the obviousness of the pedestal as the architectural complex upon which the artist would be made accessible, Piper designated a precise locality from which each element subjected to the exploitation of symbolic presence as a linguistic property (in the context of this work, her body; and therefore a politically located body) emerges as a relational experience intrinsic to the viewer’s own interaction. Similarly, I’m the Tree — with the “I” implicating both the artist’s and the viewer’s presence as the tree — is itself encircled by structures that establish distinct distances from which the experience of the tree is organized. The tree, as a body — Is it truly dead? And if so, in what way? — is presented as readily available; each of its bare parts is exposed and emphasized in space, reflected both in the immediate experience of the viewer (from their body to the surfaces of it; in its physical potential) and in its multiplication (immaterial deviations) in the reflections in the mirrors placed beneath. Through this architectural modification of space, Piper establishes a temporality affiliated with the autonomy — and therefore lack of autonomy — of this same experience, and reminiscent of earlier works (Black Box, White Box, 1992; What It’s Like, What It Is #3, 1991; Sixteen Permutations of a Planar Analysis of a Square, 1968; Recessed Square, 1967; Double Recess, 1967).

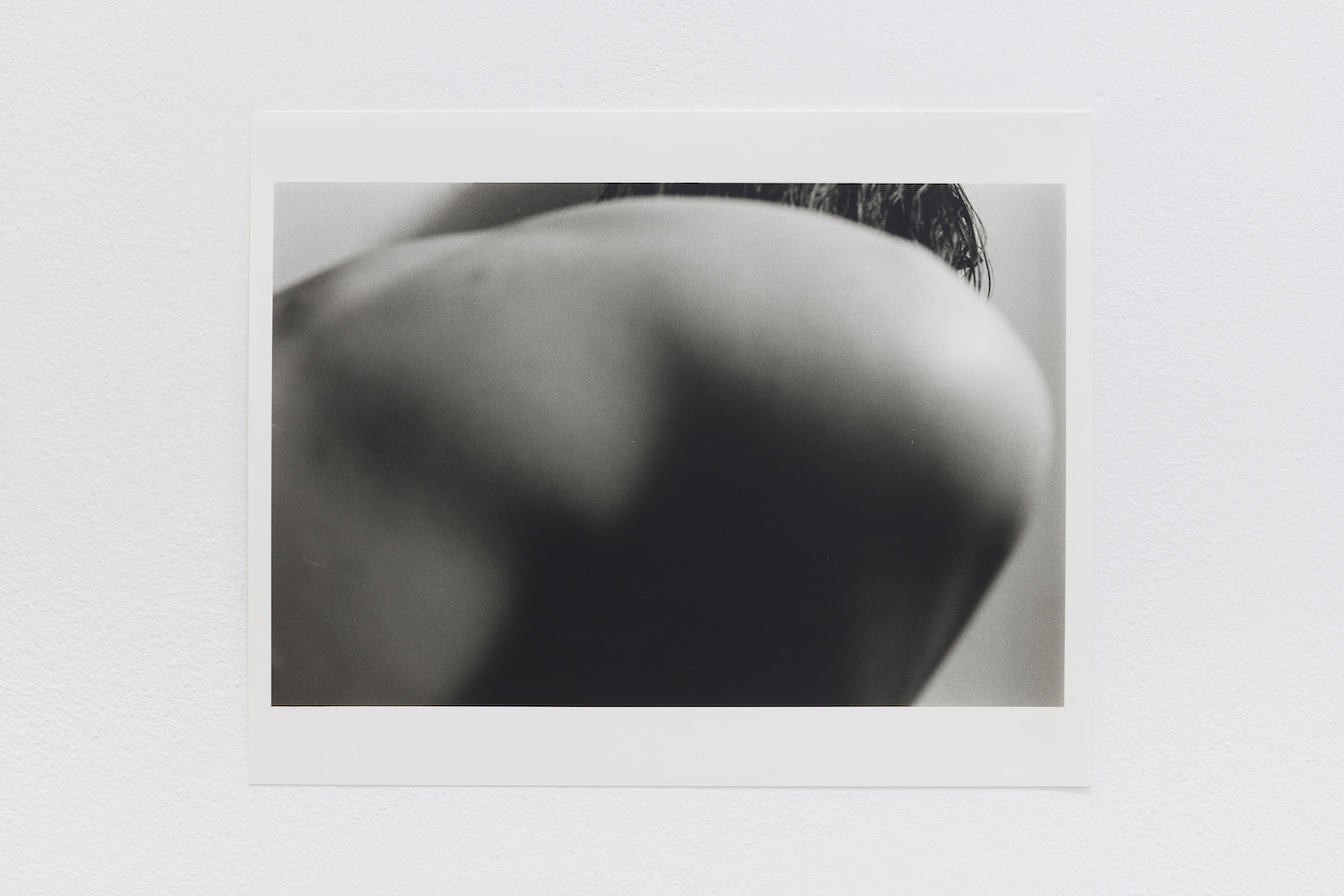

The dual potential of personified rapprochement, inherent in what constitutes the condition of the suspended tree — exposed, reflected, dependent, entirely available — traces the performative dimensions of disguise and the alteration of the self that is characteristic of the artist’s practice. In The Mythical Being (1973–75), Piper personified a male character embodied in performances and staged events, documented through a collection of photographs, drawings, texts, and newspaper advertisements, resulting in a complete alteration of her physical appearance. Through this transformation — comprising a short curly wig, reflective sunglasses, a mustache, dark pants, and, while mimicking male gestures and behaviors, maintaining a slightly hunched posture to conceal her chest — Piper sought to position her body and mantra as the signifier of her own conceptual framework: the psychology of the fictional character assuming the function of the signifier, with the context of the space of the real (an accidental public) as the signified. This process of transformation was further contextualized within both public and later private spaces, continuously positioning the artist as a witness in disguise. By engaging with zones of relational affinity as inherently reactive, Piper utilizes a set of indexes specific to information and its collective subjectivities of reception.

An essential element of “Who, Me?” lies in the semiotic connection to the notions of assumptions and prejudices. The viewer’s indexical subjectivity and experience are positioned simultaneously as primary and secondary, active and passive, included and excluded, thereby prompting visitors to engage in an active process of autonomous reconnaissance. The use of the first person (“Who, Me?”; “I’m the Tree”; “I’m the Screen”) referring not only to Piper, as an artist, but also to the viewer, operates not as a reversal but as an enclosure of all subjects located differently within sociopolitical spectrums and within the same complex, thus interrogating our respective positions in relation to concepts of accountability.

During the first generation of minimal and conceptual art, the artwork itself relied on the contingency of the viewer’s experience, thereby recognizing this experience as its own autonomous reference. However, with its extension through the work of Piper, the same contexts of conceptualization and presentation operated differently; not condensing the artwork, nor the viewer, as autonomous, but rather part of a responsive participation. In this context, the subject of the work extended beyond a unilateral self-referentiality (minimalism and conceptual art relying only on their own conceptual authority), being directed instead toward areas specific to gender, sexuality, and class — encompassing both subjective and collective ranges.

Between 1966 and 1970, with the “Hypothesis” series, Adrian Piper considered her own ability to inhabit the “universalist role of viewer that modernism promised.”2 This was put into place as a response to an understanding of political art’s imperative, and the potential for conceptual and minimal art to engage within the same realms of discourse. As such, Piper intended to apply both the work and the categorization surrounding it in relation to their potential to affect change in the viewer. While she withdrew from an exhibition focusing on conceptual art in the same period, describing in a letter “abstract forms and ideas”3 not suitable for a moment of violence and moral corruption4, the “Hypothesis” series also marked, following the same events, a change within the artist’s practice as her first experiments with a conceptual and minimal art that did not attempt to escape the realities of racism and sexism, and the refusal to indulge in the pursuit of apolitical aesthetics (understood in the work of Donald Judd, Sol LeWitt, etc.). This conceptual abstraction — a term implied by Piper — would, as such, be understood as a practice within which the same abstraction (the authoritarian discourse of self-referential objects) could be used as a tool for investigations on current situated experiences, and therefore attempt a reconfiguration: locating the work and its reception precisely outside.

Temporal injunction to the subjectivity of direct and introspective experience is equally explored in I’m the Screen (2024), wherein an installation on the lower level of the museum is defined by the arrangement of four rows of five chairs, each oriented toward a screen onto which a blank white square of light is projected. Accompanying the screen is a podium equipped with a reading lamp. No image beyond the stark white rectangle appears on the screen, and, notably, the absence of speakers ensures that no sound emerges from it. The sole visual element external to the projected white rectangle is the reflection of each spectator in mirrors placed on the walls of the room. The view of Frankfurt’s Main River through three windows is reflected within the space, extending a range of external situations inside. The spatial — and thus mental — arrangement within which viewers find themselves engenders an immediate, self-reflexive environment in which demarcations between the viewer and the viewed are detached from their limitations. Here, positioning the viewer in the exact position of the tree, exposed to their own direct and reflected gaze, Piper examines the spectator’s own agency, their participation, and, ultimately, complicity, thus precisely locating the work outside.