The exhibition “Model Malady” explores contemporary bodily states of fetishization, subversion and ridicule while using video and sculpture as means of defining what a body can be.

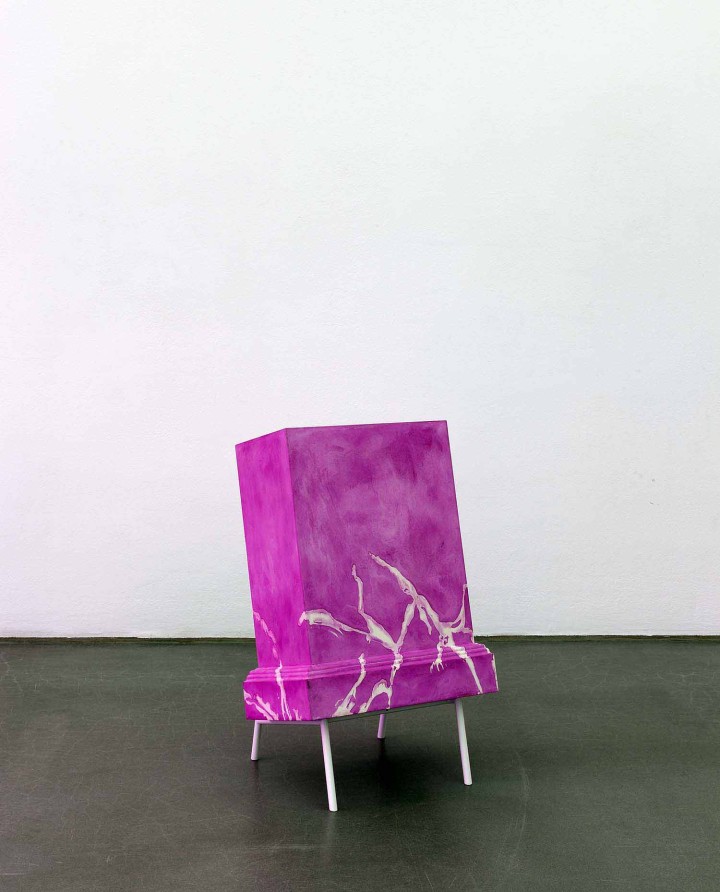

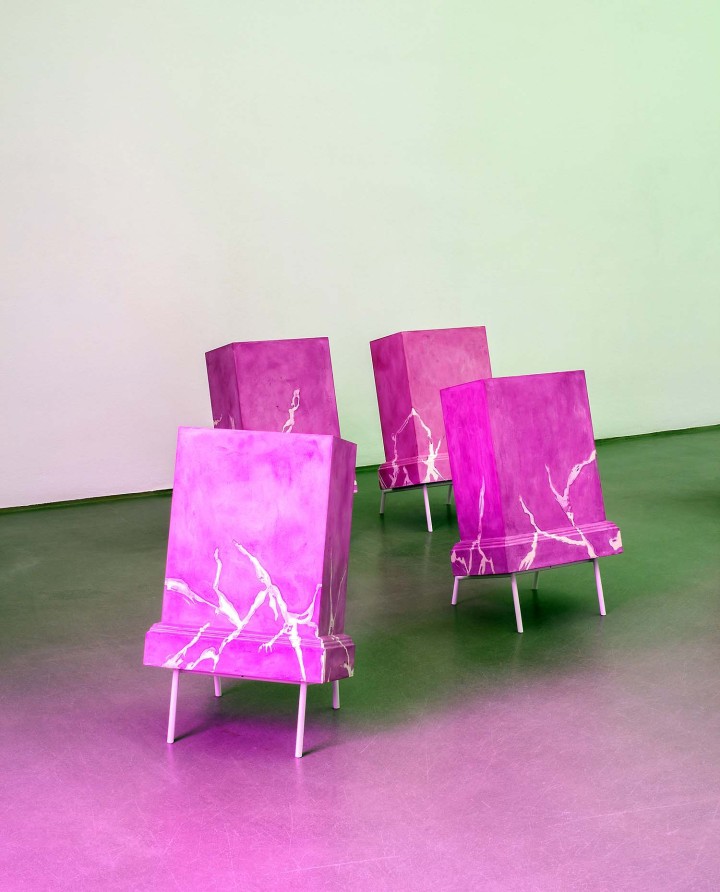

One part of the space is filled with plaster blocks stylized as faux marble pedestals “resting” on metal racks akin to chairs. Opposite, there is a freestanding vertical screen showing the new film Present Sore (2016). Presented in a 9:16 format, it not only reflects the disproportional height of the exhibition hall but takes formal advantage of the uncommon format by examining the human body in an upward progression. The video is a dynamic bundle of sporadic images in fragmented sequences, loosely choreographed around a person dressing. Through repetitive close-ups of twisting limbs, the camera doubles the choreography, as if to claim authority over the definition of the body through the image.

The installation is submerged in a pinkish light due to a colored window scrim, and a discordant sound adds to the video’s disquieting images of limbs, rotten skin and injured tissue. Going beyond the limits of the skin, the film appropriates Paul Thek’s 1965 hyper-realistic wax sculpture of freshly cut flesh. The sense of the abject challenges the slick high-definition aesthetic, and hints at the subversive poetics of the body beyond standards and surfaces.

The appropriation of Thek’s work is one more topos in Nashat’s correlation between body and object — also explored within the sculptural part of the installation by the anthropomorphized pedestals, which appear to be watching the film. They seem a bit apathetic, or even depressed; one could easily project onto them a longing for the sculptural body they once supported but that is now forever lost. The grouping is called Chômage Technique (2016), after the French term used when a factory lays off workers but maintains their salary. Nashat thus inscribes a sociopolitical dimension onto the definition of the body, suggesting an economy of useless objects — and apparently subjects, too — left with nothing but desire.