Where are your monuments, your battles, martyrs?

Where is your tribal memory? Sirs,

in that grey vault. The sea. The sea

has locked them up. The sea is History.

– The Sea Is History, Derek Walcott.

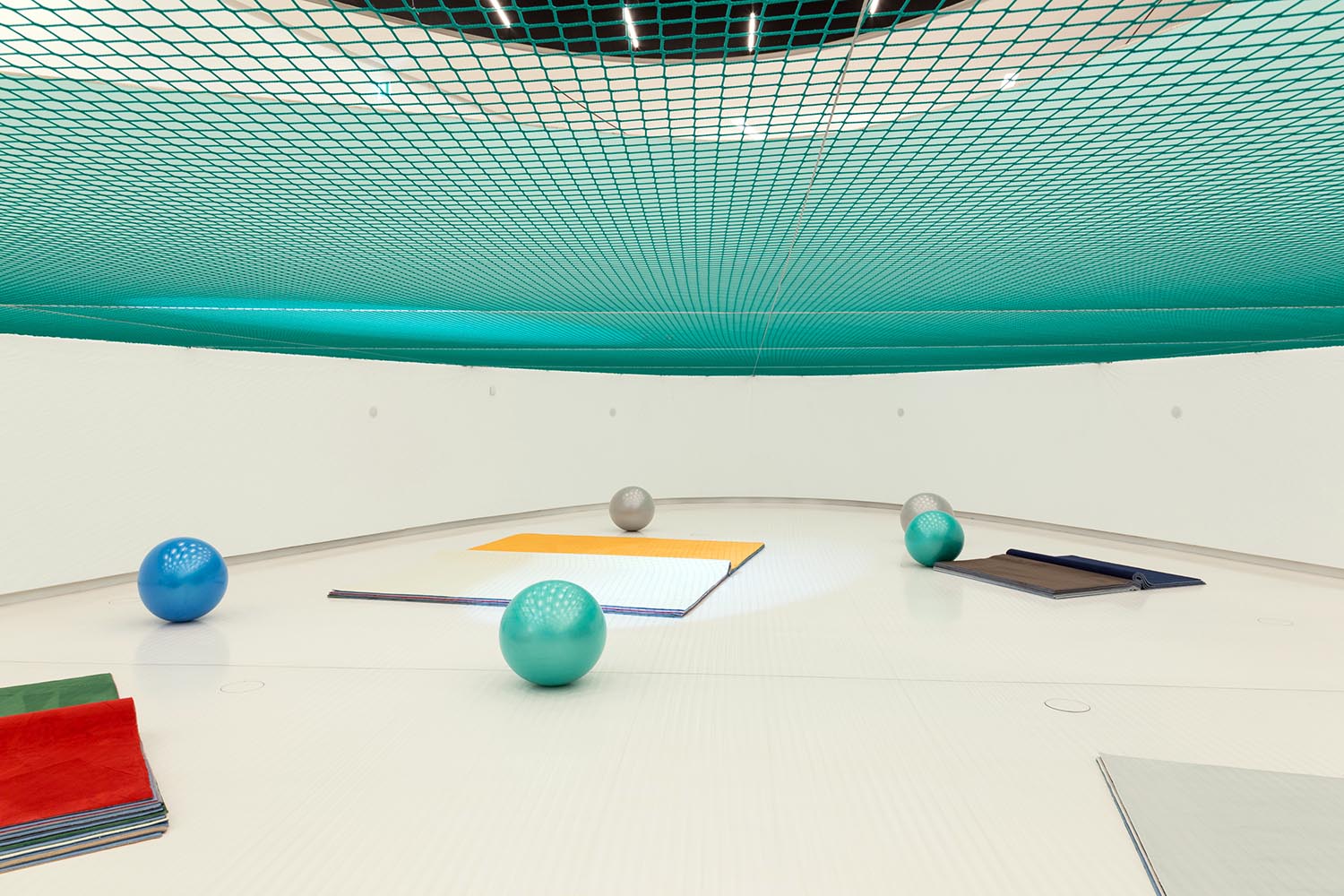

A profound reflection on rebellion and transformation, “Deadweight” at Collezione Maramotti, Reggio Emilia, presents four monumental sculptures that embody Dominique White’s vision of new worlds for Black identity, infused with the symbolic and regenerative power of the sea. The exhibitions originated from White’s winning proposal for the ninth edition of the Max Mara Art Prize for Women and was realized during a six-month residency in different cities.

The sea is also a site of impossibility, a place where time flattens and order is rejected – concepts central to White’s ongoing project Shipwreck(ed) (2018–). The exhibition’s title, “Deadweight,” a nautical term for the maximum load a ship can carry, here becomes a metaphor for subversion, with the artist reinterpreting the term to evoke liberation through the dismantling of established norms.

It all began in Agnone, where White worked in the thousand-year-old Fonderia Marinelli. Here, she learned the powers and failures of bronze in the setting of a historic bell-making institution in the often overlooked and less renown region of Molise. The second destination was Palermo, with its chaotic stillness serving as an anthropological harbor. Working with historian and writer Giovanna Fiume, White explored how roots and piracy shaped the movements of the sea and the world; geographical mapping further illuminated slavery, a long-lasting phenomenon sometimes perceived as immutable and therefore almost naturalized. In Palermo’s Palazzo Steri, an ancient prison, anthropomorphic ideas began to flow, imagining the potentiality of a person’s soul inhabiting an object. In Genoa, historical power and an affirmed colonialism conducted the artist through naval documents and archives, reviving history through her own personal eyes. Finally, Milan’s experimental Fonderia Artistica Battaglia saw the coronation of technicalities related to bronze as a permanent material, in contrasting dialogue to the artist’s usual ephemeral approach to her practice, perceived as intangible. Last stop: Todi. There, theory finally became practice with techniques like plasma cutting and 3D programming while getting used to working with molding machines.

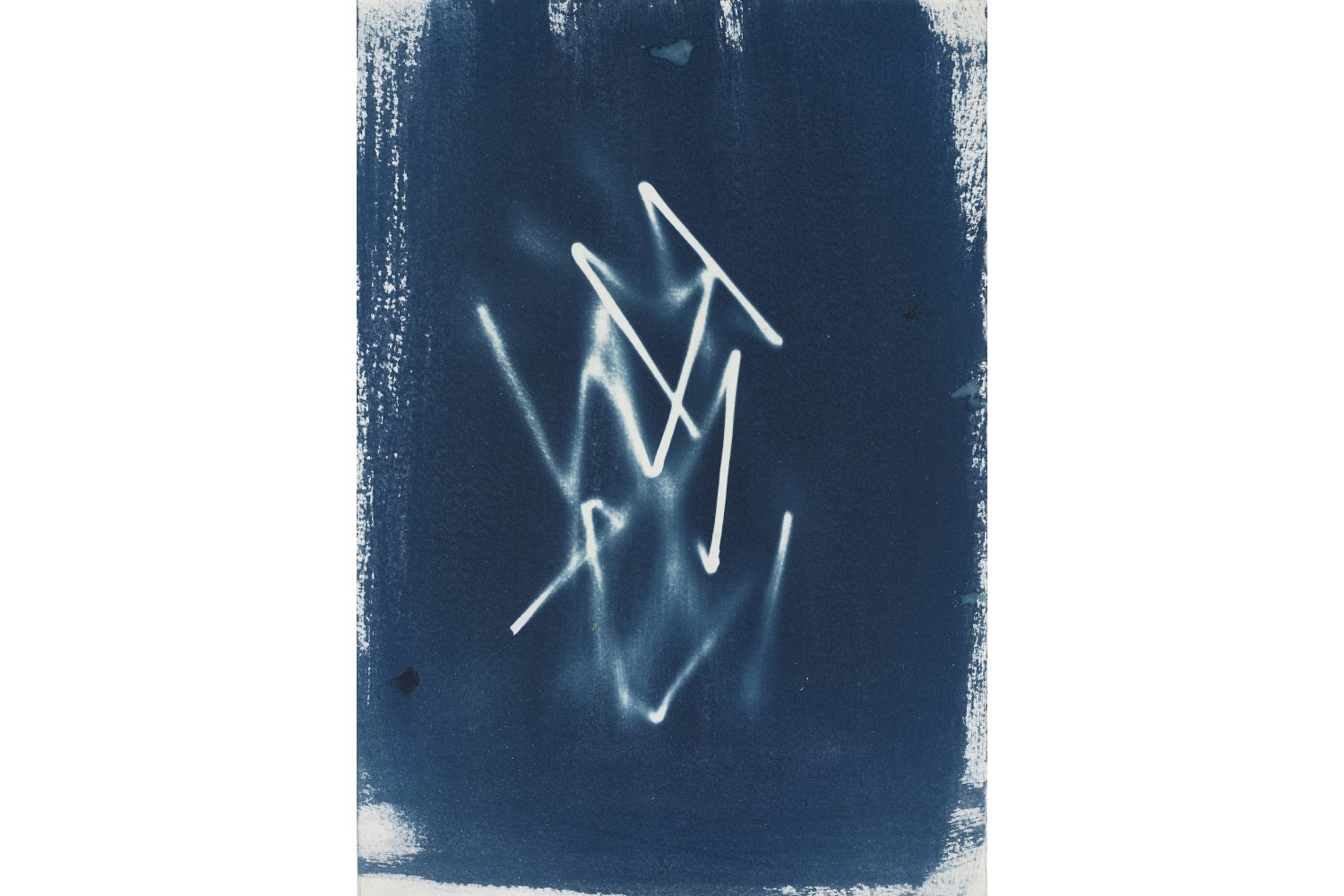

At Collezione Maramotti, White’s works blend force with fragility: their undulating, angular metal structures evoke anchors, hulls, skeletal remains, or carcasses — material forms that, through the artist’s treatment, become powerful symbols of defiance. The sculptures were immersed in the Mediterranean Sea, a physical and poetic act exploring the transformative effects of water on material objects. The resulting forms display the rust and oxidation of metal, the fragmentation of organic elements like sisal, raffia, and driftwood, and even retain the lingering scent of seawater: an exhibition of gigantic objects that are falling part in the hope that something will emerge from the ruins.

The new commission interweaves Afrofuturism, Afropessimism, and hydrarchy – concepts central to White’s research and artistic vision. Her work envisions an Afrofuture located outside traditional utopian science fiction, in an oceanic realm that offers fluid, rebellious realities beyond capitalist and colonial constraints. White’s sculptures, or “beacons,” evoke imagined, seaborne worlds that anticipate the rise of the stateless: “a [Black] future that has not yet come but must.”

“I think that’s part of why I struggle with being labeled an Afropessimist or Black nihilist — I don’t see the current situation as the only possible endpoint. Sure, some of my thinking is rooted in these perspectives, especially when my heart feels particularly squeezed. But Shipwreck(ed) looks beyond that moment. I don’t believe a future is possible without destroying the hull, and I’m certain that its destruction is possible. It’s just a matter of when, not if.”

White’s use of materials, such as mahogany — one of the hardest woods to steam and bend — and iron, simultaneously solid and volatile, symbolizes the unruliness of her practice, in which she pushes things and her body to extremes in a constant tension between fragility and brutality. Iron, notably, signifies the remnants of slave ships, marking her sculpture as a testimony of Blackness.

After encountering White’s marine monsters, a much more concrete — and yet also almost impossible to disperse — image starts to take shape in my thoughts: containers. Containers today symbolize the beating heart of globalization, representing a world interconnected, where goods travel without borders. Each container is a world, laden with opportunities and geopolitical tensions. Control over ports and shipping routes signifies national power, while the security of supply chains becomes critical in an era of uncertainties. Containers are not merely vessels; they are keys to an ever-evolving future. A future that can possibly differ from a present where big and stable ships carry an infinite amount of goods while precarious smaller ones decide the lives of unstable geographies and their citizens.

Hydrarchy, a term coined by English poet Richard Braithwaite in the 1600s, describes the ability to gain power and wealth through the instrument of water. “The idea is that those deemed as cargo, or as having limited value within the ship — pirates, runaway slaves, enslaved people, and others — could overthrow the hierarchy on board and, in doing so, disrupt the order on land as well. ‘Hydrarchy from below’ was a very real threat in the late 1600s and 1700s, and I often wonder what the world might have been like if they had succeeded.”

It is time to remap, allowing the past to sink for good and bring to surface whatever residues can help shape the future hope that White dreams of — a chance of rebirth after disaster.