If someone asked me to imagine what Diego Marcon’s studio might look like, I’d likely picture a puppeteer’s workshop. Lining the walls like lifeless marionettes would be the many characters from his oeuvre: the ceramic mutts of the “dead dog” series; the counting moles of Dolle (2023); a curiously large number of gloomy, singing children; and the melancholically homicidal father from The Parents’ Room (2021). The latest addition to this eerie, Disneyesque ensemble is Gianni and Rossana, the main protagonists of Marcon’s new work, La Gola (2024), now on show at Kunsthalle Wien.

The film, whose Italian title can be equally understood as “throat” and “gluttony,” unfolds through an epistolary exchange between the two characters, though their relationship is for the most part unclear. Although each letter begins and ends with comically brief, affectionate greetings, their content centers elsewhere, and the resulting dialogue repeatedly fails to break through the heavy incommunicability that underlies all of the exchange. Gianni delights in recounting the fabulous dinner prepared by his friend Baptiste, while Rossana obsessively details the deterioration of her elderly mother’s body, ravaged by a painful, unspecified disease. Never fully acknowledging each other, they move like parallel lines along the narrative’s crescendo, which culminates in dessert on one side, and death on the other.

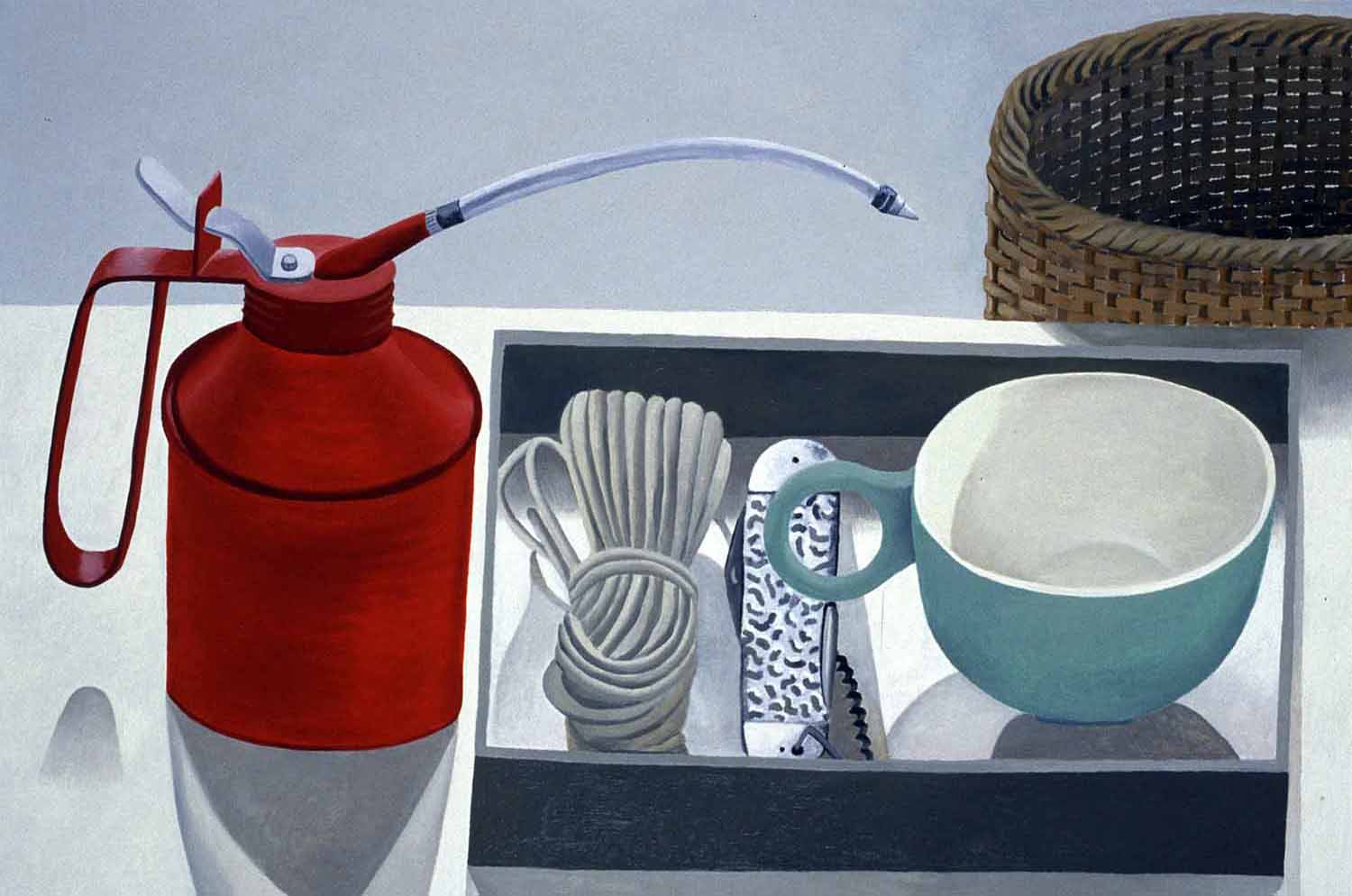

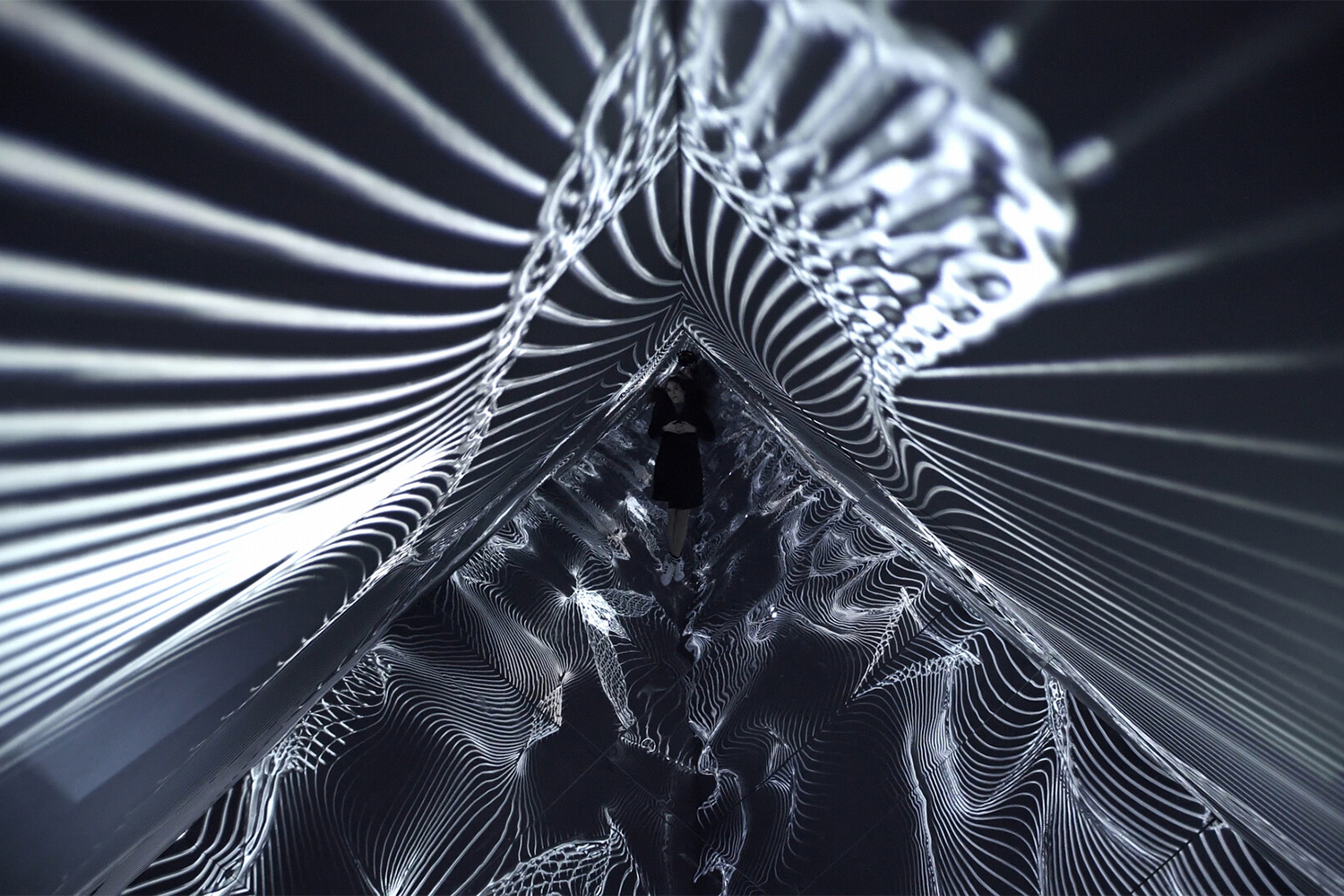

Nothing is really as it seems. A double monologue disguised as a conversation; two hyperreal silicon bodies, with CGI eyes and expressions superimposed on their otherwise completely emotionless faces; layers of fiction on fiction. Tableaux vivants, whose backgrounds have no connection to the real world, becoming increasingly abstract and pictorial as the camera closes in on each successive shot. Even the Kunsthalle space has been masqueraded, made to look like a stereotypical movie theater, with red walls, carpets, and a tiny island of seats for viewers to comfortably watch the film. The small number of chairs invites visitors to roam around the empty, crimson room and become part of the dramaturgical setting of the work.

Marcon shows the same penchant for artifice as those Baroque cooks described by historian Piero Camporesi in The Incorruptible Flesh (1983), trained in the refined art of formal illusions and flavorful disguises: armor-shaped dishes, fish-tasting beefs, fried-looking roasts. A kitchen governed by “a culinary poetics of surprise, the unexpected, the wonderful,” aimed at sensory delirium and rational loss. “Torta Fedora, the bakeable Baroque!” exclaims Gianni in his final letter. The soundtrack itself, composed by Federico Chiari and played on the organ of Bergamo Cathedral, is reminiscent of Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in D Minor (1704–1750s), one of the most recognizable melodies of the period; the music swells as the sense of loss grows and the viewer’s emotions are put to the test.

La Gola is an unsettling watch. Narratively, Gianni’s disregard for Rossana’s suffering is, by turns, exasperating, painful, and darkly humorous (“Dear Rossana, today, risotto!” raised a few chuckles in the room). Rosanna’s grief — though initially touching, human even — slowly grows more unsettling as she mercilessly describes, as if surgically dissecting it, her mother’s ailing body. Which brings me to another linguistic strategy employed by Marcon as a means of tinkering with the viewer’s emotional response. Culinary and medical languages are ordinarily kept separate by socio-moral taboos; throughout the letters, the artist juxtaposes the two repeatedly, blurring the sacred boundaries between human flesh and the kitchen, as luscious delicacies and repulsive pus mingle uncomfortably in the mind of the viewer.

None of this appears on the screen, of course, as everything is kept entirely on a discursive level. In Marcon’s own words, “there is nothing but language.” Vienna is no stranger to similar ideas, being the home of such word-players as Freud, Wittgenstein, or Bernhard, one of the artist’s favorite writers. Gianni’s obsession with food does not stem from hunger; Rossana’s fascination for her dying mother’s body seems to lack real empathy. Both speak for the sake of speaking, unsentimental marionettes trapped (and we with them) in a theater made of someone else’s words. La Gola’s two meanings find ulterior connotation: the throat, after all, is also one of the main organs of speech; and gluttonous is the desire to encompass the whole world in one sentence, to exhaust it through language.