Messe Wien Halle D, the shiny new home of Vienna Contemporary, provided a perfect shelter from the torrential rains that violently hit Eastern Europe over its opening days. Celebrating its tenth edition, the fair looked to renovate its image, moving from a relatively regional event to a must-attend stop on the international art world’s agenda. More space, more art, more money: as dark clouds gathered around it, a timid atmosphere of optimism filled the lofty, brightly lit hall.

This year brought some novelties, starting with the fair’s newly appointed artistic director, Francesca Gavin, who greeted me at the entrance. Having recently moved to Vienna, the London-born writer and curator has rapidly emerged as one of the most interesting players within the city’s art scene. Enthusiastic and experienced, Gavin is determined to take the Austrian capital to the next level, while preserving and promoting the unique qualities that, in her opinion, set it apart from other European art centers. “It’s one of the few capitals where people can afford to live, and people can have studios, and there are more project spaces than everywhere else.” Vienna is less about the hustle and more about the art, she says; the event should be a catalyst for what can happen in the city, drawing attention to the existing local production.

To this end, the fair runs concurrently with two other important art events: “Parallel,” a site-specific show found this year in the historic Otto Wagner Areal, dedicated primarily to emerging artists; and Curated By, in which galleries invite international curators for a special round of exhibitions, such as Marika Kuźmicz’s selection of self-portraits at Galerie Elisabeth & Klaus Thoman, or Kristian Vistrup Madsen’s investigation of the history of formalism at Charim Galerie Wien. In this context, Vienna Contemporary aims to take the lead and act as an accelerator for the existing energies scattered around the city, providing a cool, comfortable stage for the international art world to gather, network, and spend.

At a time of general crisis and creeping anxiety, with art sales stagnating and a global shift toward what feels like darker times (the art market is not indifferent to global events), the fair tried its best to focus and invest in the future. Its new hall, updated budget, and expanded selection of galleries felt like good-luck amulets and colorful distraction. This was reflected in most booths, as galleries opted for a safe, neutral curatorial approach to the space. There were some notable exceptions to this trend, such as the Viennese Galerie Hubert Winter, winner of the Bildrecht SOLO Award, presenting Davide Allieri’s nausea-green drawings encased in thick, handmade fiberglass frames; or Karina Mendreczky, Katalin Járay Kortmann, Pavla Sceranková, and Lucia Tallová’s installation at Tomas Umrian Contemporary (Bratislava), which felt like catching a glimpse of a fantasy or a fairy tale, the brown soil on the floor subtly defying the hall’s sanitized interior.

Both were found in the main section of the fair, dedicated to established and emerging galleries alike, with a total of around one hundred participants. While a third were Austrian, another third came from Eastern Europe. Vienna Contemporary has long prided itself on offering a somewhat unique assortment of artists, as many of the spaces represented here would not normally have the chance to show at larger, Western fairs such as Frieze or Basel. The significant number of young, emerging artists provided some interesting encounters. For example, at VARTAI (Vilnius), Monika Radžiūnaitė’s canvases, with their medieval, geometric, tapestry-like quality, conversed with Neringa Vasiliauskaitė’s intricately crafted sculptures, intense and dark as forest moss, under the painted blue gaze of Donata Minderytė’s portrait. At WHOISPOLA (Warsaw)’s booth, Jędrzej Bieńko’s shadowy and murky paintings, together with Marianna Rodziewicz’s uncanny ceramics, and Sebastian Winkler’s eye-catching paper-collage nude, created a delightfully eerie tension as they offered a cadavre exquis-like investigation of the human form. Aleksandra Liput’s thorny, muddily glazed urns grabbed my attention (Le Guern Gallery, Warsaw), as well as Paula Gogola’s figures, cool and sharp like a metal blade (VUNU Gallery, Bratislava).

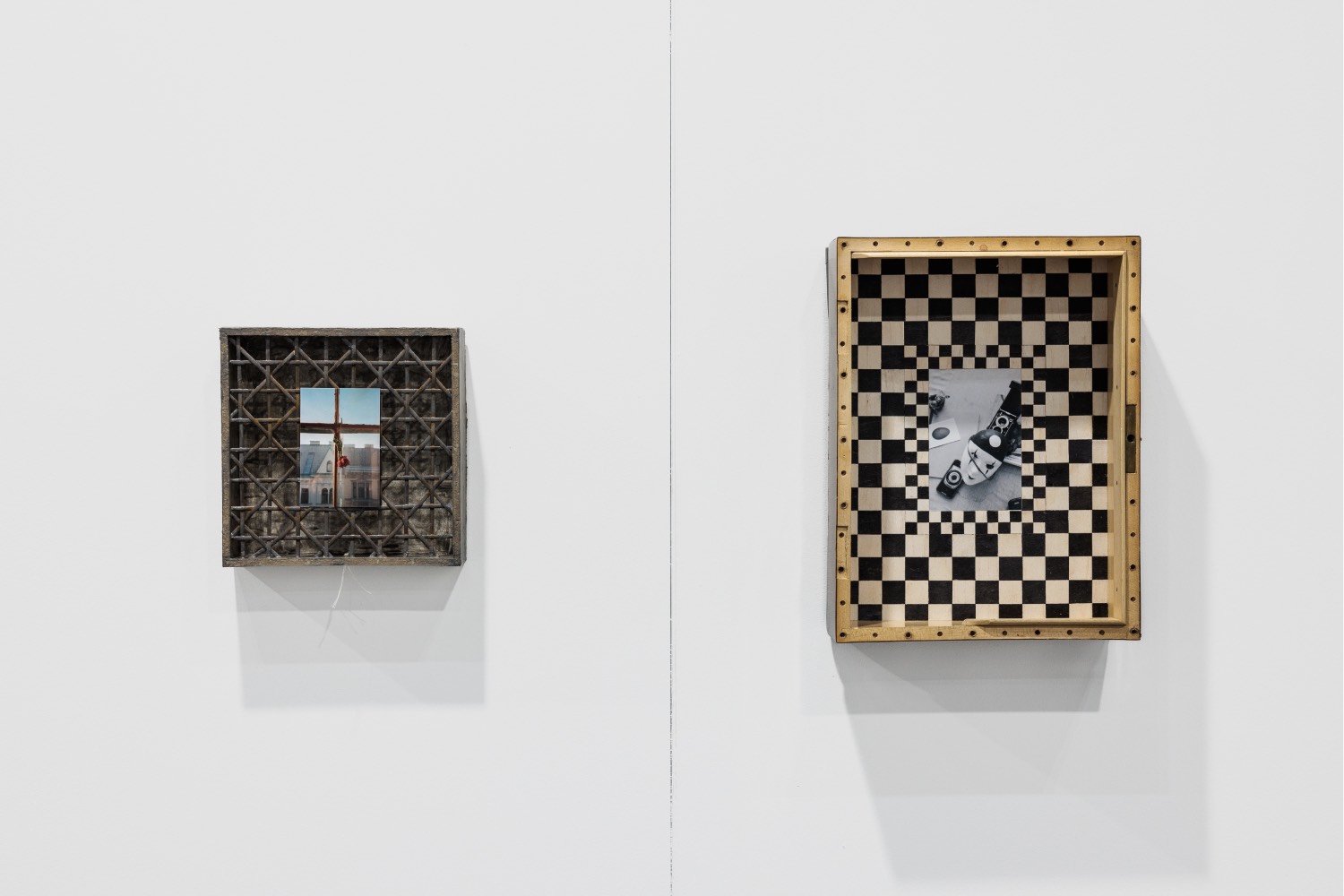

Figurative painting unsurprisingly dominated the fair, with a prevailing focus on the bodily. Yet, there were exceptions: I stood in awe before Luke Libera Moore’s elegantly designed, deceptively marbled microscope, Coping Mechanism #1: Longing Engine (2024) (ASHES / ASHES, New York); Ernst Yohji Jaeger and Yasuaki Hamada’s tiny wooden boxes whispered to me in a quiet and mysterious language (Croy Nielsen, Vienna), discreet riddles in the great chaos of the fair’s hall. Lisbon gallery Pedro Cera brought together some of the fair’s most interesting sculptures: Isabel Cordovil’s beige leather Pillow bulge (2024), Bekhbaatar Enkhtur’s flat copper Tiger (2024), Paloma Varga Weisz’s jelly-like homunculi Wilde Leute 1 (2024), and Oliver Laric’s aluminum Norway Maple 5 (2024) made the booth stand out. A mention must go Vienna’s MEYER*KAINER for perhaps the most effervescent combination of works, with Flora Hauser’s joyously colored yarns on canvas providing the perfect backdrop for Kris Lemsalu’s praying assemblage figure. This year’s edition also saw the growing participation of Italian galleries, with ZERO… (Milan) and RizzutoGallery (Palermo) offering a fascinating insight into the current state of the art in the region. While the former opted for a more cryptic and conceptual aesthetic with Hans Schabus’s sculptures and Irene Fenara’s ghostly photographic series (winner of the LUKOWA Acquisition Prize), the latter presented two artists, Francesca Polizzi and Daniele Franzella, whose works masterfully engage in a dialogue with the history and landscape of the Mediterranean.

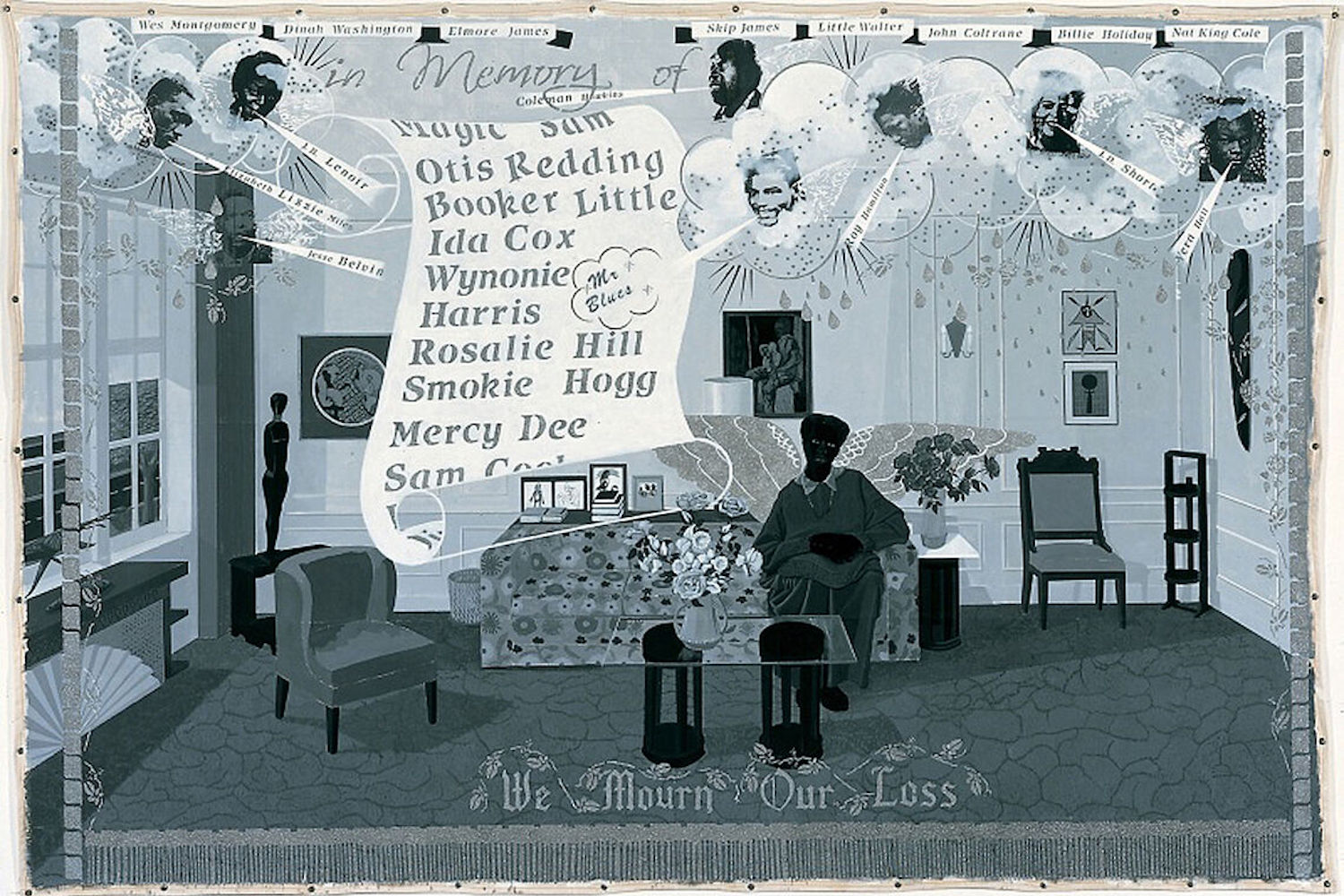

An art fair is not a biennial, that’s clear. But is it possible for such an event to go beyond its commercial mission to include and produce critical discourse? Inviting outside curators can sometimes be an effective strategy. This was the link between the three other sections of Vienna Contemporary: ZONE1, Context, and VCT Statement. The first, a selection of ten artists under the age of forty who live, work, or have been educated in Austria, was curated by Bruno Mokross, founder of Vienna’s Independent Space Index. While the section didn’t stand out much from the rest of the fair, I was particularly taken with Nanna Kaiser’s patched and worn out sculptural couch (Shore Gallery, Vienna) and Noushin Redjaian’s glittering romantic tears (Galerie Ernst Hilger, Vienna), for which she won the viennacontemporary Collectors Prize. A few meters away was the newly created Context area, curated by Pernilla Holmes, dedicated to drawing attention to forgotten or marginalized figures in Austrian and Eastern European art history, with particular focus on women. Among them, the neo-Gothic photographic work of Hungarian artist Zsuzsi Uji (acb gallery, Budapest) was the most interesting discovery.

Given the event’s commercial setting, VCT’s statement was definitely the most ambitious experiment of the three: its mission, as stated on the fair’s website, is to “link sociopolitical phenomena with the art world, support conversation, and highlight artistic awareness through collaborations with external curators and thinkers.” After the last two editions focused on the war in Ukraine and immigration, this year’s theme was energy production and sustainability. Some of the works stood out for their inventiveness, such as Judith Fegerl’s delicate, alchemical experiments; Linda Lach’s posthuman assemblage of metal and milk; and Katrin Hornek’s sandpit populated by turtle-shaped telephones. I found myself hypnotized by Sara Bezovšek’s video installation www.s-n-d.si (2021), with its looping apocalyptic images of natural disasters. What I was seeing on the screen felt so remote, in the way that catastrophes often do when viewed on social media or on the phone; yet right outside the door, the Danube was overflowing, disrupting the metro’s normal service; that same morning, the tree in front of my apartment had been torn down by violent winds; even Parallel, which was supposed to run concurrently with the fair, had to close its doors to visitors because of the abnormal weather.

While the section promised a corner of quality critical thinking, the space didn’t feel visually distinct enough from the other booths to suggest that something different was trying to take place. Caught up in the commercial, neoliberal spirit of the fair, its potentially disruptive and political nature felt partially lost. The fact that the exhibition will continue beyond the event at the Salzburger Kunstverein suggests to me that this problem was not entirely unanticipated by the organizers.

In a talk on the relationship between fairs and the cities that host them, Eric Schlosser, the art director of the Tbilisi Art Fair, insisted that these events have the potential to fulfill a “public mission”: supporting artists, creating visibility, and promoting creativity, certainly, but, above all, upholding freedom of expression. He cited the case of Slovakia, where the new government has made severe cuts to culture, starting with contemporary art. “Democracy is under attack,” he commented. With the right wing poised to win Austria’s upcoming legislative elections and Vienna Contemporary at a turning point in its identity, one can’t help but wonder if the role of a fair might be more than making its participants richer and sheltering its visitors from the rain. The energies are there, but only time will tell.