I wrote a draft of this review while returning from Munich on September 6th. Just a few hours later, on that same day, the news of Rebecca Horn’s death was announced. During a walk-through of the exhibition with one of the curators, Jana Baumann, we discussed how emotional and appreciative the artist felt when she made an unannounced visit to her own solo show, revisiting her artworks. That moment will remain a significant part of Haus der Kunst’s legacy.

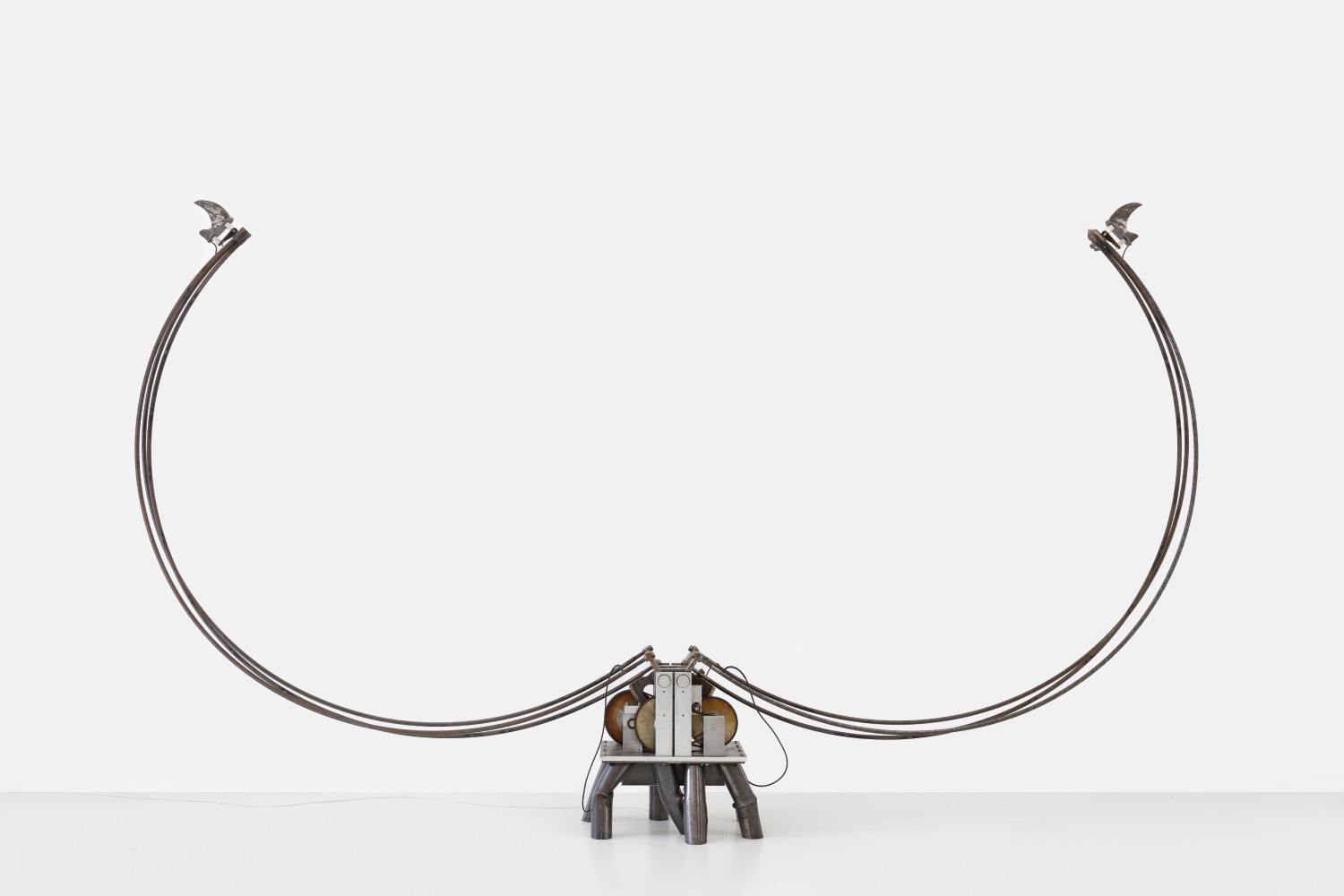

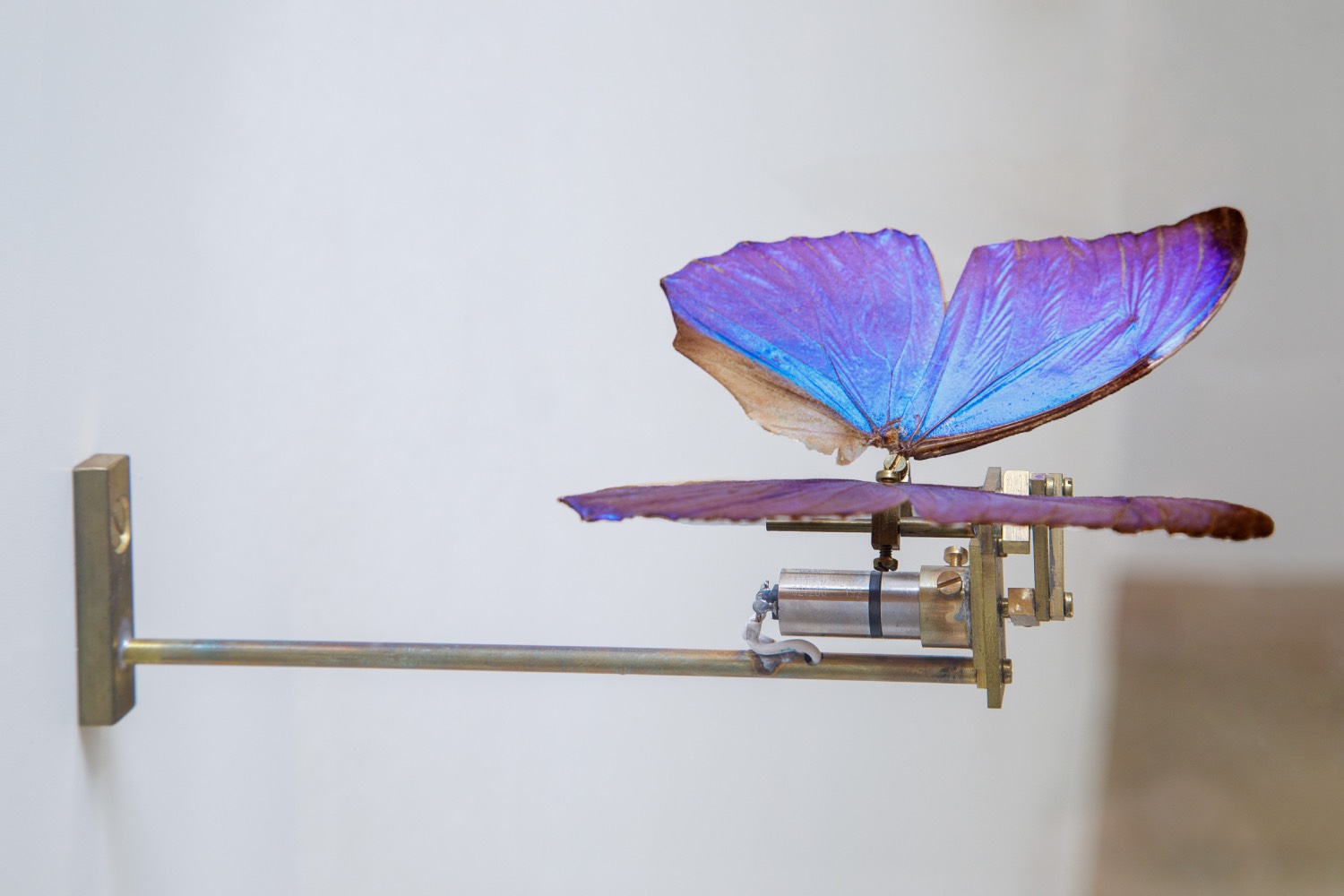

Born in Michelstadt in 1944, Horn was a prominent figure in the feminist art movement. Her work, associated with body art since the 1960s, separated the female body from its traditional ties to nature and motherhood, and resonated conceptually with those of other experimental and performance artists like Marina Abramović, Yoko Ono, and Valie Export. The exhibition at Haus der Kunst presents a comprehensive collection of her works, exploring the many phases and complexities of her diverse career, which had evolved from feminist themes to critical reflections on the potential dangers of technology overshadowing our humanity. Primarily identifying as a choreographer, notions of dance and movement significantly influenced much of her work, which encompassed both graphic art and sculpture. Additionally, through her performances, she explored the body’s sensuality in relation to its surroundings — another key element of her art. This exhibition serves as a narrative of the most versatile artists of our time. Horn deftly wove together space, light, physicality, sound, and rhythm to create a unified experience. In her performative, sculptural, and cinematic works, transformations into machines, animals, or the Earth illustrated existence as something that is visible, tangible, sonically impactful, and invariably understood through the body.

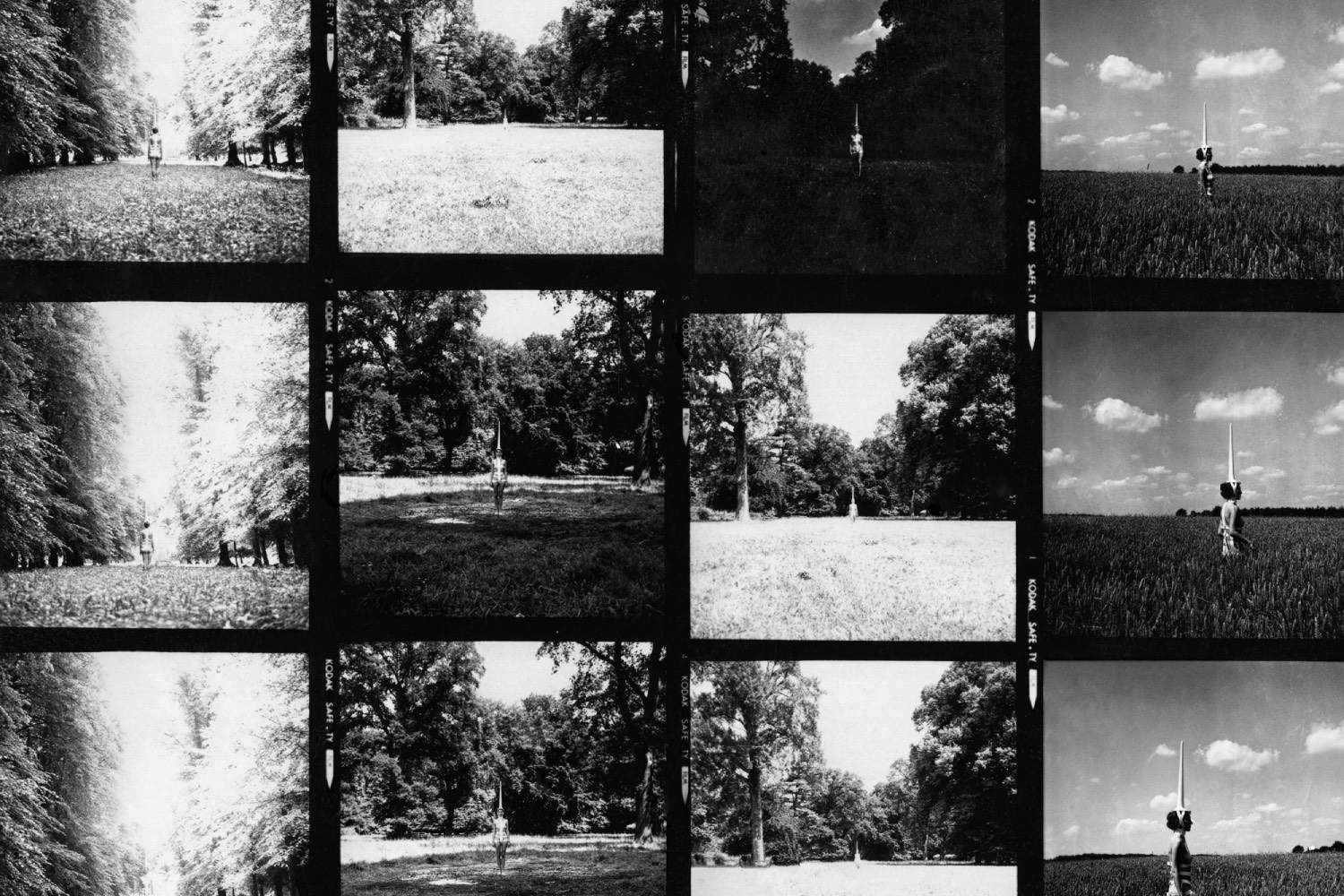

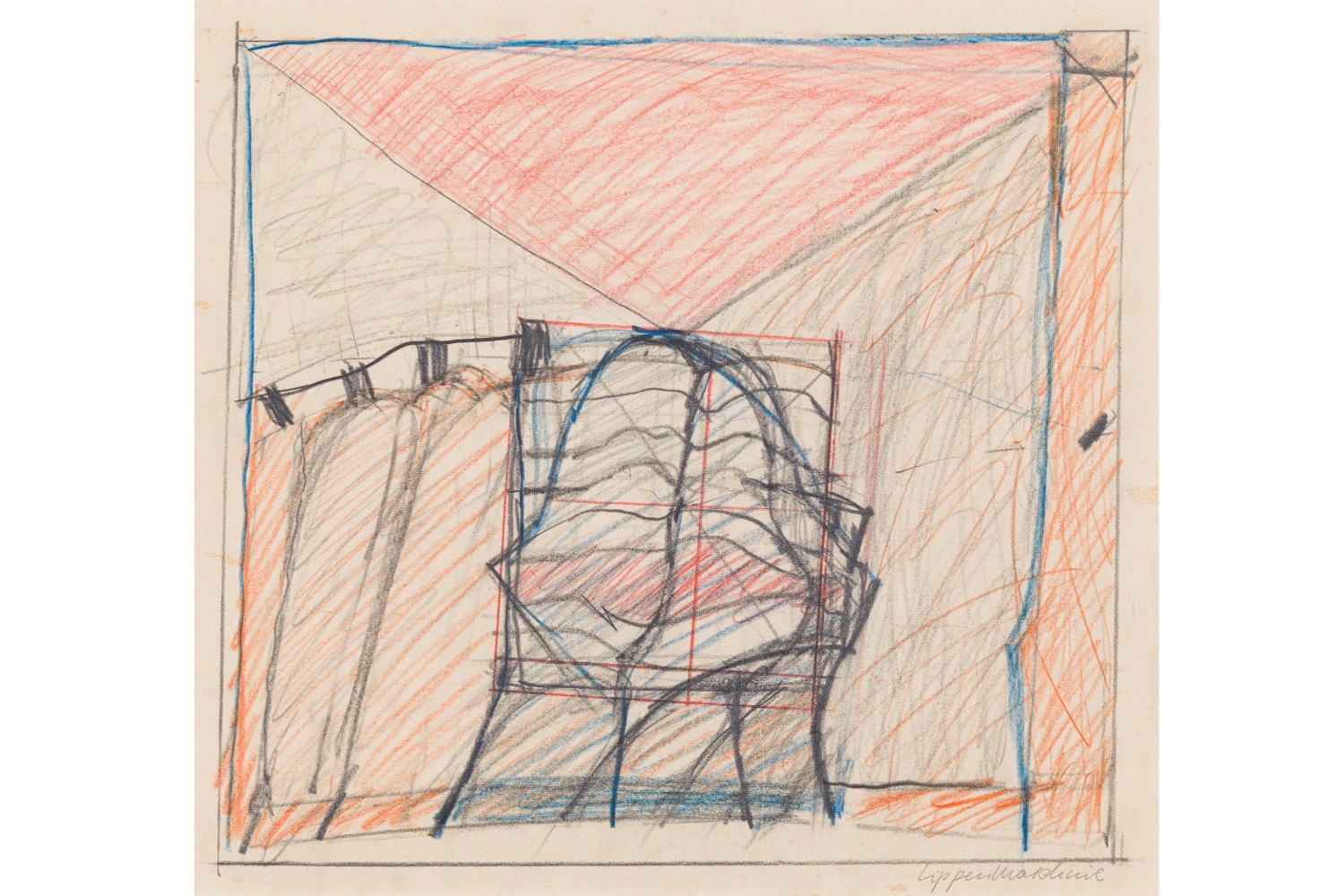

In Horn’s work, bodies serve as vessels for a variety of objects. Feathers, horns, fans, pencils, and pigments are all used to playfully engage the concept of incorporation. Her early works on paper from the 1960s and her performances and short films from the 1970s investigate the body’s potential for extension, reflecting behavioral studies that encompass aesthetic gestures, female constraints, mechanical bodily functions like torsion, and an undeniable affinity for flight. Horn’s sculptures challenge us to contemplate the body from a kinetic perspective or in relation to repetitive motions. Her bodies, enhanced by artistic “prostheses,” are more of a commentary on nature than mere representations thereof; Horn envisioned an architecture of the body influenced by the matriarchal strength found in the geometric Art Nouveau of Austro-German design, infusing elements of unsettling surreal delicacy to express a subtle sensuality that extends beyond physicality to the intellect. Her relentless pursuit of transformation, even at great cost, was at the heart of an artistic vision that explored how bodies become something else entirely. In this regard, Paul Delvaux serves as a notable iconographic reference.

Horn’s work doesn’t merely enact gender reversals or incorporate chance into deliberate acts, as Nancy Spector has pointed out; her “machines” resonate with the radical techno-feminists described by Donna Haraway, who harness “male” technology for their own liberating aims. Her creations from those dynamic and contentious decades reflect the combative revolutionary dialectics of Jean Sorel, reinterpreted through a feminist lens, much like how Ronald Reagan rethought John Kennedy’s economic policies. The jokes and historical references interweave a complex structure of ideas that, regrettably, have often been overlooked, though their insights could have proven beneficial if recognized in due course.

The exhibition represents the first thorough evaluation of the performative and choreographic aspects of her work. Throughout her career, Horn utilized the language of dance as both an artistic medium and a driving force behind her vision. From her early endeavors, she developed innovative symbols to encapsulate the relationship between bodies and technology. This theme progressed from her initial works on paper works in the 1960s to performances and films of the 1970s, mechanical sculptures in the 1980s, and expansive installations in the 1990s, continuing to the present day.

Through her artwork, Horn emphasized the connections between human and nonhuman entities, challenging the traditional view of humanity as the central figure among various species. Her creations are intricately interwoven with references to literary, artistic, and cinematic legacies. Horn’s artistic path signifies a profound exploration into humanity’s shifting role within the expansive universe.