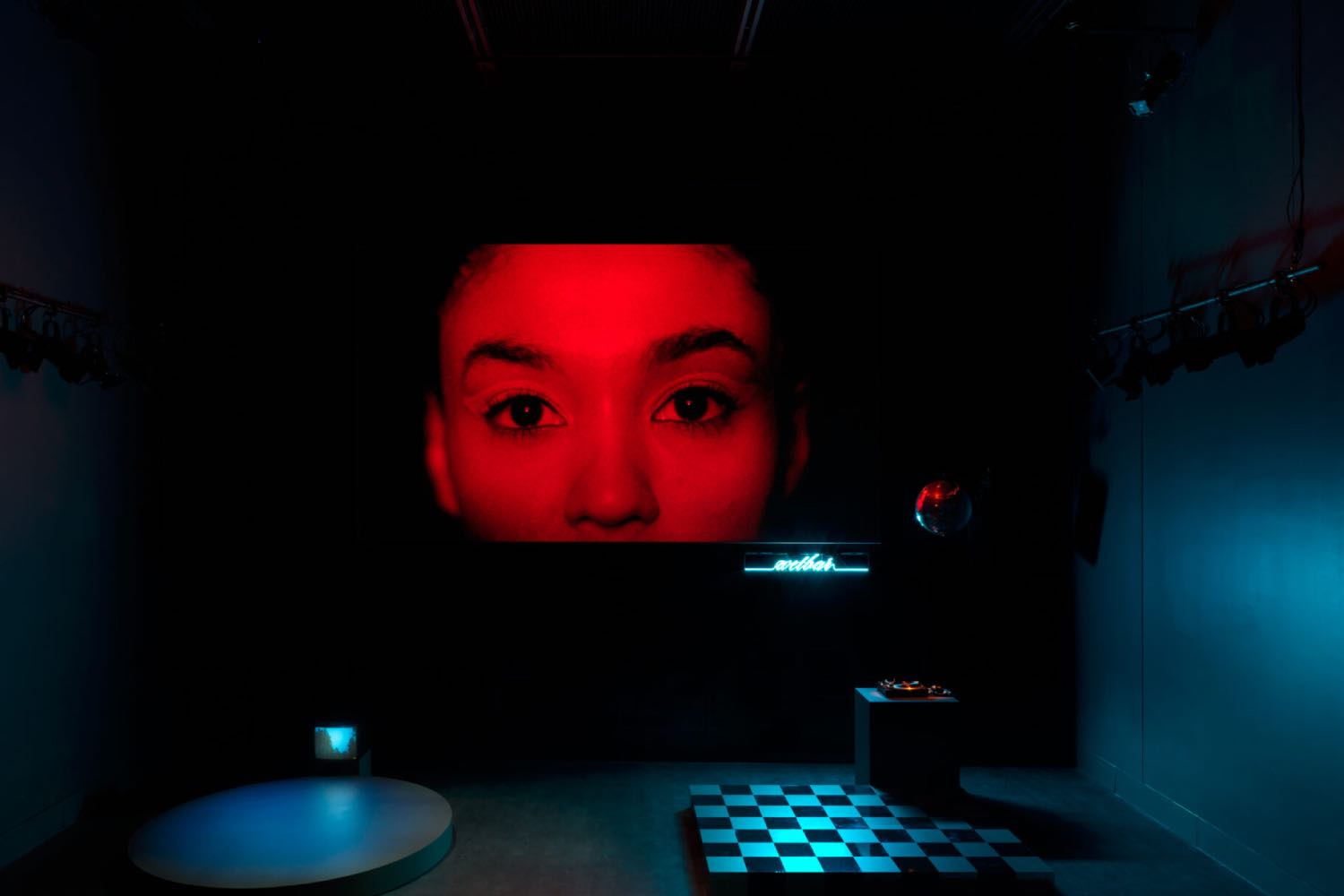

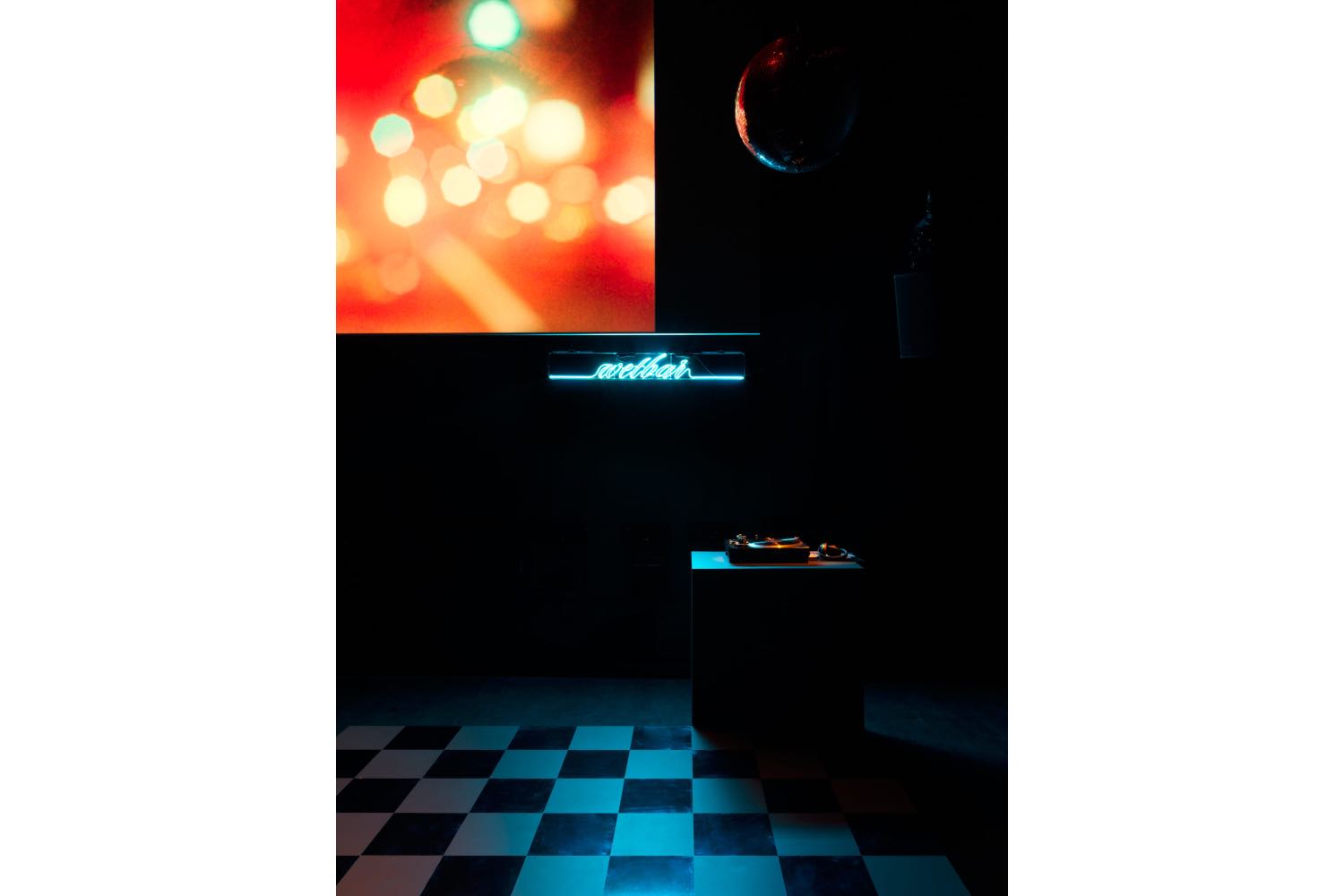

“Opera means work, let me work it,” states American artist Sable Elyse Smith in the program for her ambitious new performance If you unfold us (2024). “Let it do that mythic thing of spectacle it does and let me put the story in it; the everyday stuff of living and breathing and loving and wishing and weathering and looping like tapestries – all of it, once again, living is persistent.” Smith’s current residency at MoMA’s Marie-Josée and Henry Kravis Studio unfurls across two distinct but interwoven projects: the video installation Weather Report (2024) and the aforementioned If you unfold us, which marks the artist’s first solo foray into live performance. Both featuring lush orchestration from jazz composer David Dominique and vocals from artist-musician Shala Miller, the pieces tell a fragmented but emotionally resonant story of two Black women, Main and Lover, as they navigate their romantic relationship amidst Main’s journey of self-discovery and an ever-present weather crisis. Ahead of the opening night of If you unfold us, Smith and I discussed her creative process across different mediums, working collaboratively, and how language factors into all aspects of her creative work.

Madeleine Seidel: To start off, I wanted to talk about how you conceived this project and how long you’ve been working on it.

Sable Elyse Smith: I’ve been telling people that I was making an opera since maybe 2018 or 2019, and then I had a false start in late 2019. Then last June, Martha [Joseph, MoMA Assistant Curator of Media and Performance] invited me to meet up for coffee – you know, the curator investigation. I did this sound-related curatorial project “Beneath Tongues” at the Swiss Institute in 2020, so she asked if there were other similar things that I was interested in doing or wanted to follow up on. I was interested, but I told her I’ve been thinking about an opera for a long time. When she offered me the opportunity to do a project at MoMA, I thought “well, it’s the perfect vehicle to try this thing in, so why not?” and that became my deadline.

MS: The deadline was real at that point.

SES: The deadline was really real [laughs]. The deadline is still real. We’re still putting pen to paper.

MS: Speaking of your Swiss Institute project and also of “Mirror/Echo/Tilt,” your 2019 project at the New Museum with artists Shaun Leonardo and Melanie Crean, both of those exhibitions were collaborative. If you unfold us is also a collaborative work between David Dominique, Shala Miller, creative director Naima Green, and everybody on your crew. Multiple teams, all coming together. How did you approach working so collaboratively, this time on a live project?

SES: The simple, boring answer is that I like working with people and I like being in conversation with people. The simple, boring answer is that I like working with people and I like being in conversation with people. Shala and David were so integral to this project. I’m bad at remembering timelines, but in 2021 or 2022 a friend sent me a video of Shala singing, and I was immediately drawn to her voice. I was inspired by her sound, and honestly, we all became musical pen pals as David does not live in New York. We sent a series of fragments and ideas back and forth because we couldn’t be in the same room together too often. And as challenging as it was, something truly amazing came out of it. I personally put a lot of trust in the process and just tried to be responsive to how the process developed or shifted.

MS: You wrote the lyrics for the libretto featured in Weather Report and If you unfolded us. How was translating your writing, which you’ve incorporated into many other projects, to music with David and Shala?

SES: The timeline we had could have been four years’ worth of work collapsed on top of each other. So, there were times where one step in the process happened first and it leads to the next thing, and there were times where we figured out a way to weave the music, lyrics, and text together, even if the steps weren’t in a traditional order. Instinct, intuition, and constantly building a shared vocabulary was important. Shala focused on writing the melodies, and sometimes, just hearing a word in a new way would prompt an editor addition I would make to the text. We had to be constantly responsive to any element presented by the team and uncover the possibility in those things–even if we were unsure about them in the beginning. There were a lot of lovely surprises that came about here.

MS: Were you conceptualizing Weather Report and If you unfolded us as being standalone pieces?

SES: Definitely. That was important because who knows if the performance will ever be produced again? It’s huge. Even with this project, or at least the performance, I tried to scale it down to the most manageable, efficient piece possible. There’s only two voices and the set is minimal, but still, the financial impact is substantial. I was thinking about performance documentation and other ways to experience it, and the idea of a concept music video made sense as something that had more permanence and is more accessible. It could have its own sort of life as this series of videos and songs.

MS: Although your earlier exhibitions at MoMA PS1 (“MOOD: Studio Museum in Harlem Artists-in-Residence, 2018-2019”) and the Queens Museum (“Ordinary Violence”, 2018) both featured videos, audiences are likely more familiar with your two-dimensional or sculptural work from your recent gallery shows at JTT and your inclusion in the Whitney Biennial 2022, “Quiet as It’s Kept.” How did it feel going back to a medium that you had not shown publicly in a while, and how do you conceive your video work versus your sculptures and works on paper?

SES: The way that I came into artmaking is through video and film. In college when I was thinking about grad school, I was going back and forth a writing program or a filmmaking program. I ended up at neither, but whatever, life happens [laughs]. Writing – language, storytelling, narrative, poetry – and moving image feel like the foundation to my art education. It has always informed how I think about making art, even if it isn’t incredibly obvious. I’m always tinkering with video work, but for whatever reason, the public opportunities for other bodies of work have come up first.

MS: One of the motifs you incorporate in the video is the concept of weather – hence, Weather Report. Why did you choose to make that element so central to the project?

SES: The word or even the idea of weather has these different guises. It could be the literal weather ¬– the tumult in your atmospheric environment – but I also thought about references to the weather in other projects, too, such as theorist and writer Christina Sharpe’s idea of the weather as a metaphor for the climate of our sociopolitical environment.

That felt important as an anchor or shorthand to creating a story that feels very individual and mundane, like seeking love or trying to decipher one’s affections for another person or themselves. But the characters in this project are two people living in this contemporary world, so there are all these other structures that impress upon them and interfere with the everyday sort of aspiration or notion of love that are beyond their control. I wanted to insert that information into the story in a way that doesn’t center it – it just acknowledges that this is the reality. It can do all this different work depending on what information you bring to the piece or how you’re looking at it.

MS: It’s clever way to keep that sense of conflict or even trauma present.

SES: But not in a salacious way.

MS: Yes, it’s not so much in the foreground that it’s a distraction to the stories on-screen. Something I wanted to chat a little bit about is next week’s performance.

SES: Yes, it’s right here!

MS: Is this the first time that you’ve done a live performance at this scale?

SES: Yes, definitely.

MS: What are your thoughts about having this live work of yours premiere?

SES: I mainly feel curiosity. When you’re in something for a long time – and I guess this happens to me when I edit video, too – you anticipate what’s supposed to come next, or, you know, you’ve made this decision that this is the image you’re supposed to see. You must step away from something for a bit and come back with fresh eyes. That’s like writing, too. When you’re writing a narrative, there’s the exploratory writing that happens, there’s the story you think you’re telling, and then once words get on the page, there’s the story that you are actually telling. I’m curious to find out what that is here.