Trevor Yeung evokes the Hong Kong of his childhood from within that other island city of Venice. Like Venice, Hong Kong holds a strategic position in colonial narratives. It was ceded in perpetuity to the United Kingdom after the First Opium War as a “crown colony,” and exists now as a special administrative region of the People’s Republic of China.

Operating as a decorative conceit while also facilitating the arbitrary functions of a place — its FedEx service, refuse collection, food supply — water binds Venice and Hong Kong, as it does Yeung’s work and many of the other works at this year’s Venice Biennale. Presented under the theme of “Foreigners Everywhere,” these works confront and reframe colonial narratives and the bodies of water that helped shape them. In “Courtyard of Attachment,” Yeung transforms a courtyard and several rooms of a nineteenth-century warehouse just beyond the walls of the Arsenale into a series of watery propositions that evoke “his father’s seafood restaurant, pet shops, feng shui arrangements, and the fish he kept as a child,” as Olivia Chow writes in an accompanying text. But Yeung’s practice is also about “deconstructing cultural symbols,” and these works conflate the aesthetics of Hong Kong’s Chinese-influenced interiors — peppered with lucky symbols and talismans — and the glass exteriors of the city’s shoreline into a series of stylized, glassy, chromatic installations that hold water not as their liquid but as their substance — or rather, subject.

In the courtyard a series of prismatic stainless-steel racks, with chrome edges that glare in the midday sun, house glassy fish tanks through which the city’s lagoon water is run, filtered, and returned to the waterways. Yeung’s work is concerned with botany, horticulture, and aquatic ecosystems, the fragility of marine life and its relation to humankind. The rejuvenation of water is a gesture of care but also relations, which is marked here not by presence but by absence: these fish tanks, complex water filtration systems, and plastic bags of water for pet shop fish are bereft of animate life. Titled Pond of Never Enough (2024), the work in the courtyard is defined by its undulating and corrugated metal pond frame like a reimagining of a decorative water feature, but lined with the kind of deep-blue plastic sheeting reminiscent of childhood paddling pools and emitting a nostalgic aura in the heat. Nearby, a series of lotus flowers — symbolic, in Chinese culture, of purity — lounge in ungainly plastic pots. The constituent parts of the pond are familiar, but as a whole, it becomes uncanny and sets Yeung’s proposition for the show, in which water is both ornamental and functional, playful and fundamental to life. Recalling his pet fish and a tradition of human-animal care, Yeung brings culture and nature to touch in a confusion of boundaries that extends to identity building. He challenges nature in the Western sense of the word; it reminds me of Donna Haraway’s A Cyborg Manifesto (1985), in which the eco-feminist and scholar proposes the cyborg as a conflation of human and other life, “resolutely committed to partiality, irony, intimacy, and perversity.”

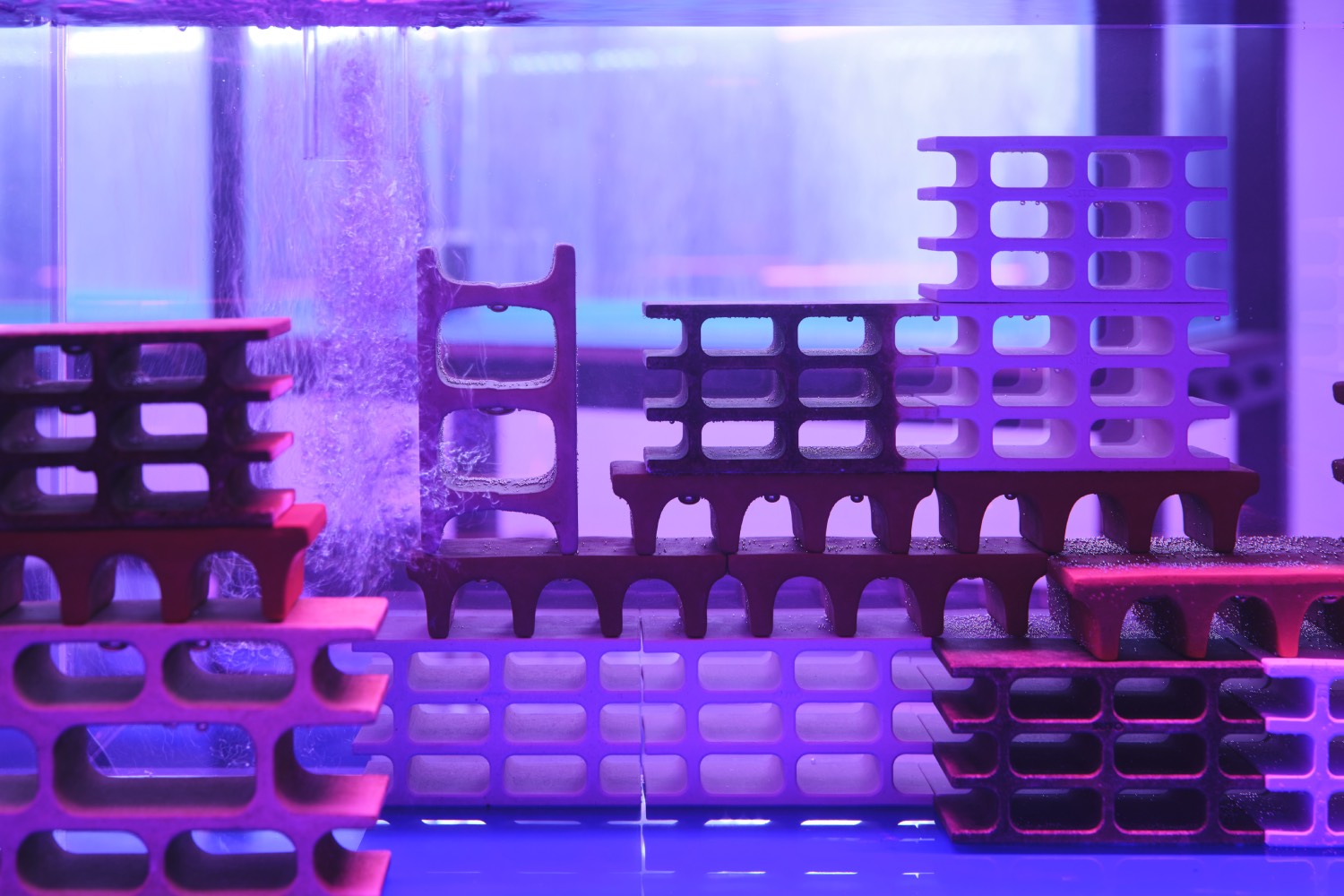

Upon entering the dark windowless interior, we are welcomed by a pair of old Chinese desks housing traditional fish tanks replete with rocks, two-dimensional underwater scenes, and a hard white neon light. Titled Two Unwanted Lovers (2024), the installation evokes the foyers of Hong Kong’s business establishments. A nearby cabinet with its door ajar reveals an LED nightlight shaped like fantastical fungi, titled Night Mushroom in Shade (Teak Cabinet) (2024). Meanwhile, a glass jar of distilled water titled Salty Lover Venice (2024) resides on top of the cabinet — fed over the course of the exhibition with salt collected from the walls of the room. Mounted on a large acidic-yellow quartz plinth across the room is another fish tank containing a series of rotating rose and gold quartz orbs, said to bring fortune and wealth. Hanging from a stainless-steel grate around the doorway to the second room are a series of clear plastic sacks — the kind that fish are sold in at pet shops but here absent of life. There is something sterile but also tactile, almost delectable, about Yeung’s play on water; many of the works, like this one titled Gate of Instant Love (2024), signal a relationship between water and desire as things that are fluid but that can also hold, at the same time implicating Yeung’s own identity as a queer person into the picture.

In the second room a single fish tank is suspended on a high Chinese lacquer table-cum-plinth. It is connected to a complex series of tubes and pumps, exposing the reality of water pollution and conservation, but perhaps also the absurdity of preserving an island like Venice that is sinking. With its cumbersome pumps and systems, and aptly titled Little Comfy Tornado (2024), the tank reveals that absurdity as a human desire, and failure, to control its environment. The final room is lined with fish tanks, like a pet shop, and backed with mirrors and glowing neon-pink light so that while we move through the space, we become the tanks’ only living and transient inhabitants. In Chinese culture, water is the root of all things — water that Yeung points out is bound in want — as in desire — but also loss — of life, of land, of identity through colonial violence. Beyond the cultural specificity of Hong Kong or Venice, Yeung speaks through water as a universal language — or a point of relations — that whispers like a saline dream.