Apocalypse is a trendy word today, and our reality is blurred. Life, at least as we knew it pre-pandemic, has led to raging waves of genocide, accelerated machines with brains on steroids, and an inability to cross cultural or ethnic divides without looking over one’s shoulder. What surrounds us is uncertain, though contemporary artists are occasionally in tune with these shifts we sense.

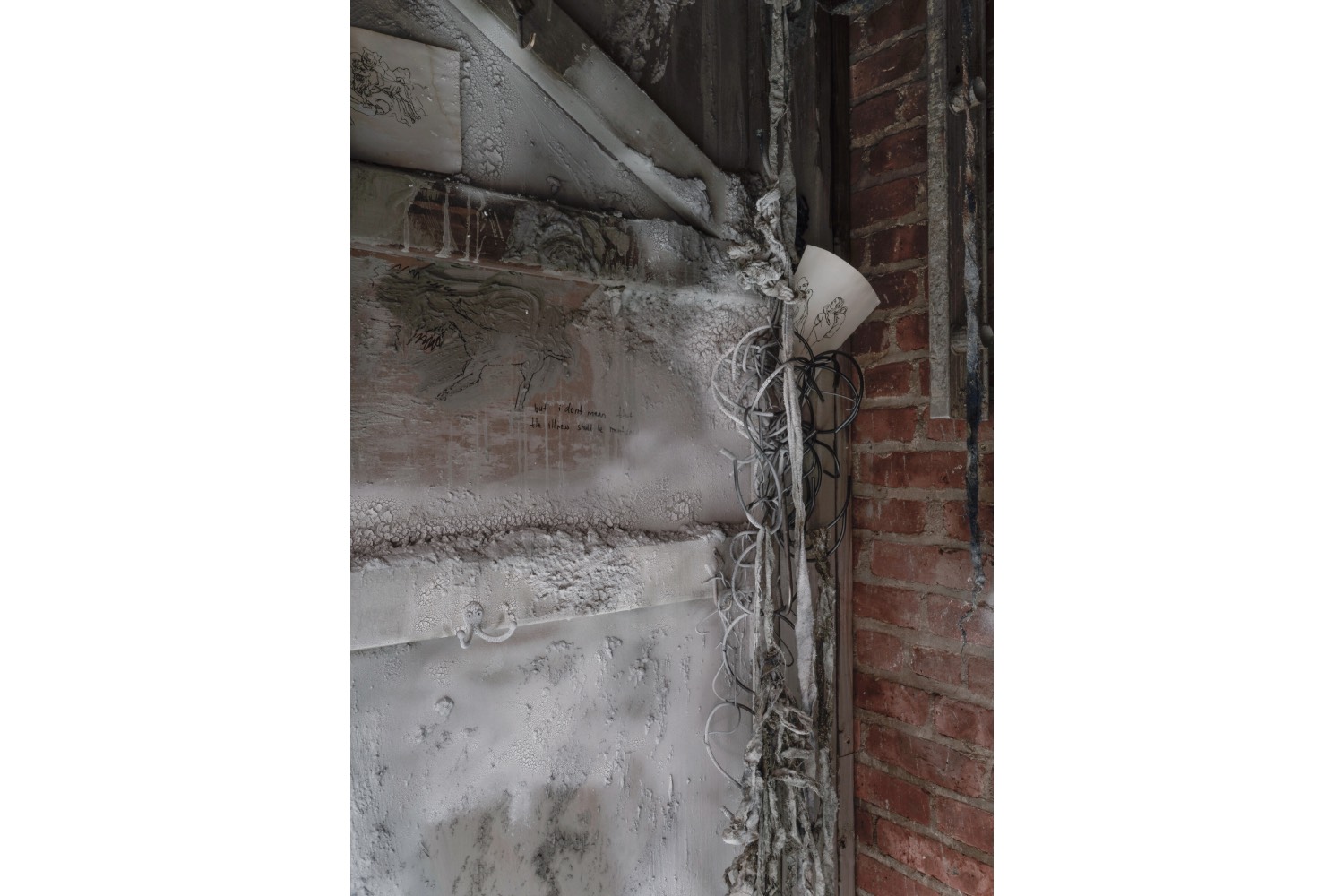

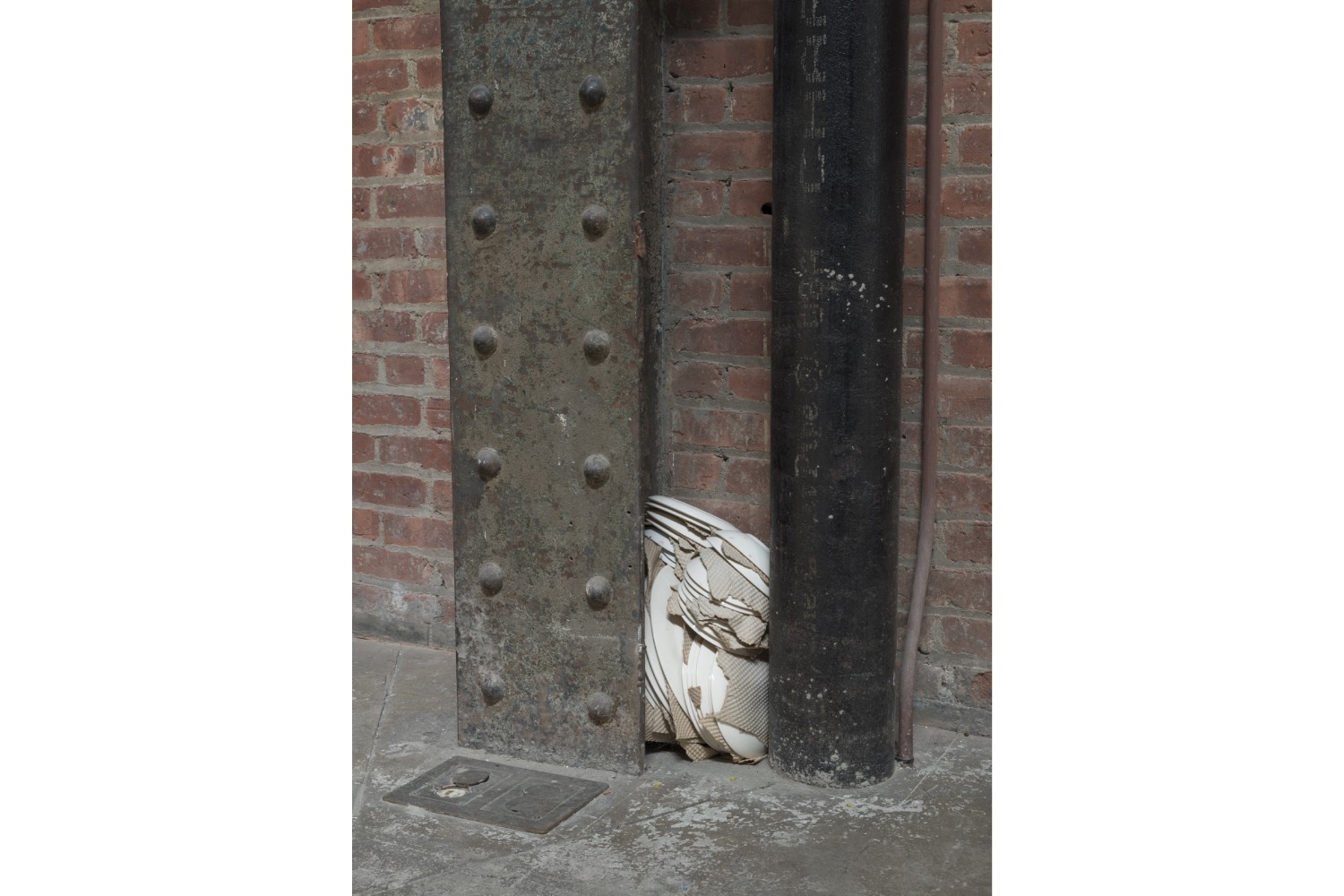

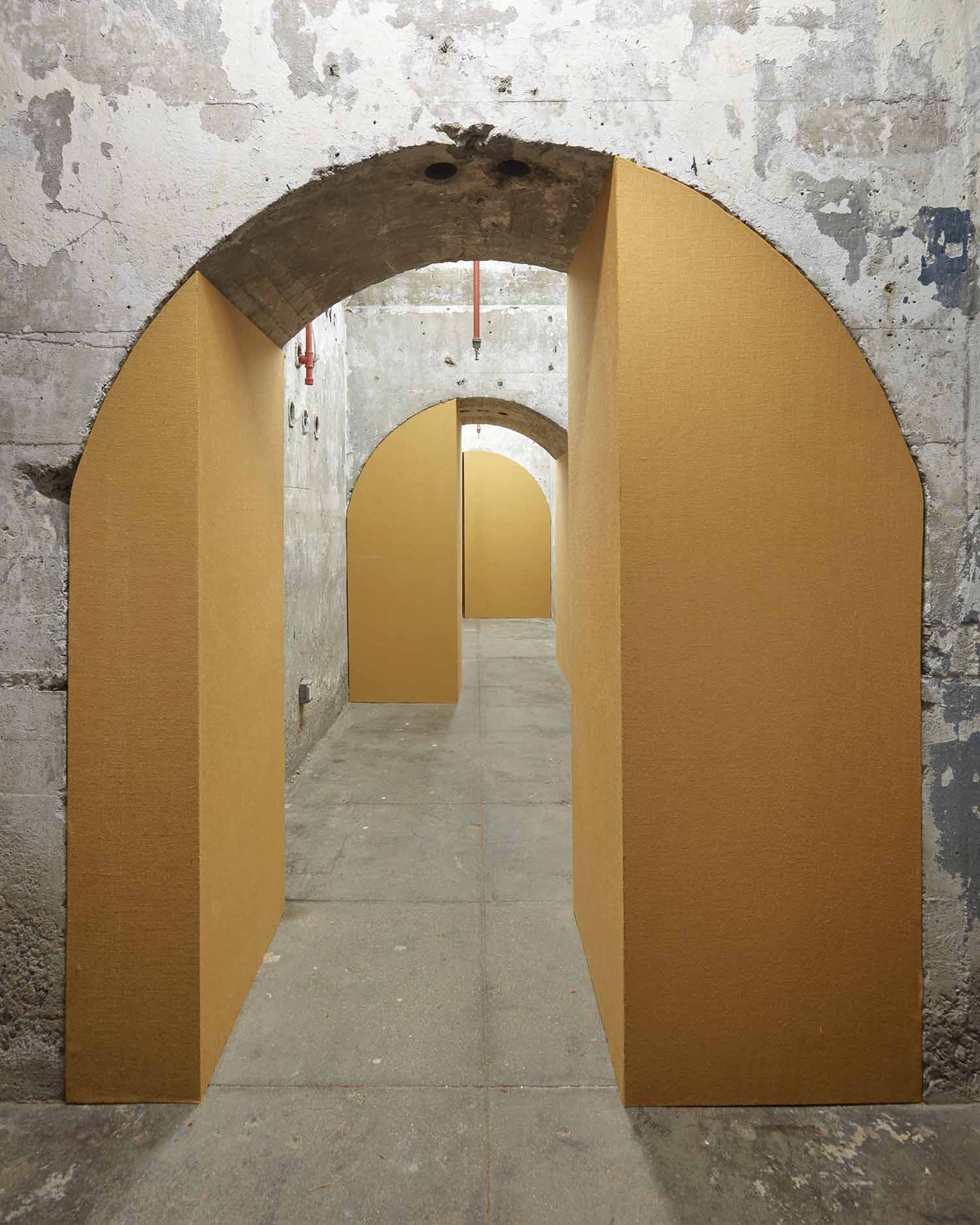

Entering the dark postindustrial cavern of SculptureCenter in New York, now reconfigured by Berlin-based Georgian artist Tolia Astakhishvili, one feels like a passerby entering a once burgeoning and now fully deserted town somewhere in Eastern Europe. A rectangular installation, Can’t Stop Living (2024), surrounded by two vertical chutes, stands as the center point of the exhibition. Life is deciphered through traces left behind: by a pile of detritus the artist has collected in Berlin, Tbilisi, and New York, and brought here to become integral to bigger abstract sculptures constructed from plasterboard, cement, wood, coffee, and metal grates, among other materials. In Astakhishvili’s words, she sees these chutes as filtering devices through which we pass all our deeds, histories, and emotions.

The geometrically sound Euclidian pieces of the artist’s vision, curated by Kyle Dancewicz and Christopher Aque of SculptureCenter, are constructed to delineate the space, diffuse its impact, and envelop a viewer on many different levels. One point of analysis is the perception of time, as there are two distinct models of it to be found here. Everyday circadian cycles of living are seen in drawings by Astakhishvili, works of contributing artists she has selected, and in the film I Remember (Depth of Flattened Cruelty) (2023) by Astakhishvili in collaboration with James Richards. The film, presented on three separate screens, is a collage, a poetically meandering and intentionally blurred documentation of other works and installations. Humans throughout the work are not seen as living; we see them as fossils, as some now-deceased form of social structure. Lefebvre’s theory of deconstructed space and ambiguity of linear time is very much on point. Time flows through SculptureCenter and the viewers, but changes within the built-in structures and presented works.

Nuanced representation of figures and faces are carefully selected and positioned organically within constructed spaces. The artist, in collaboration with Ketuta Alexi-Meskhishvili, Zurab Astakhishvili, Kirsty Bell, Katinka Bock, Dylan Peirce, and James Richards, offers a synthetic yet diffusive discourse between distinct practices. Fabric- and paper-based prints, sculpture, collage, and text-based works underline the in-between aesthetic of the exhibition. All of these works, selected by the artist, support her vision of discursive cooperation as a means of bringing out additional layers of meaning.

This coevolution of the environment also subverts the former trolley repair shop, home of Sculpture Center since 2001. Situational logic reflects on our material consumption and our unbelievable material waste. Human discourse is not relevant here; emotions have seized existence. Astakhishvili achieves a lofty goal of constructing reality through the spaces she puts together, yet she manages to take her identity out of this construction. Although she composes the space, her sympathies or dislikes are unknown, similar to entering the deserted chambers of the patriarch in a novel by Gabriel García Márquez.

A distinctive visual personal reference also comes from a familiar post-Soviet landscape, self-referential to all those who come from that part of the world. Tbilisi, Berlin, Almaty, Warsaw, Tashkent, and Yerevan –– all have stretches of prefabricated greyness, stretches from a hopeless totalitarian past where the collective was glorified at the expense of the individual; where privacy was discarded for the sake of an Orwellian transparency enforced by fear. Astakhishvili’s self-referential landscapes, created from the detritus of lived lives, mean to provide this same type of mysterious purgatory. While entering it we encounter traces of childhood, postcolonial traumas, body parts, and fragmented faces; we meander through the labyrinth hoping that we will go to the very end, yet we all perceive this ending differently. Writing this from Georgia, where a pro-Russian government is pushing against the will of its West-oriented youth, I do hope that this time the ending will indeed be different.