What does George Baselitz want to confess? What are his sins? These philosophically heavy questions are raised by the title of his major exhibition at White Cube London’s Bermondsey space: “A Confession of My Sins.”

The exhibition gathers more than fifty new paintings and works on paper that, at the age of eighty-six, the artist has created just within the past year. There’s a profound sense of grandeur and, perhaps, even finality about the show, positioning itself in conversation with the canon that Baselitz is so deeply embedded within. “I’ve got my early childhood drawings of eagles, stags, deer, dogs and so on in folders,” Baselitz has stated, reflecting on his influences and earlier sketches, processing a life that has led ultimately to the fragility and vulnerability of old age. Indeed, this exhibition could very well be Baselitz’s last major showcase while he’s still living.

Scale, whether large or small, has a way of reeling the body into question, urgently in the case of Baselitz’s paintings. Most of these works are probably larger than the rooms (or houses) lived in by the vast majority of their audience, and this is significant: the architectural scale of these paintings immerses the viewer in a peculiar engagement.

Blaue Augen Rehe (Blue Eyes Deer) (all works 2023) is a painting measuring 305 by 480 centimeters, portraying two oversized deers, seemingly caught off guard, with uneven plastic blue eyes that stare hypnotically — and somewhat hilariously — at the viewer. The vivid blue eyes pull the viewer in until their field of vision is the surface of the painting itself. The viewer stands alone with these two dazed deer, who dissolve into a dazzling array of brushstrokes and splash marks that become quantum and unfixed in their rendering.

All of the works in the exhibition are portraits of one kind or another. In many of them Baselitz appears upside down, often sitting alongside his wife, Elke. The upside-down figures, so synonymous with Baselitz, might be understood as a mechanism to captivate the viewer; but specifically with these paintings, it is the scale of the work and the physics of the materials and mark-making that draws the viewer in for closer inspection. What is revealed by a closer look is an anthology of expressive marks and the labor of the making itself. Marks on the canvases from Baselitz’s painting cart read as expressive gestures that are punctuated by dusty-looking footprints. Baselitz paints these works by laying out the canvas on the floor of his studio, making the painting while standing on it and in it, often using the painting cart to support his movements.

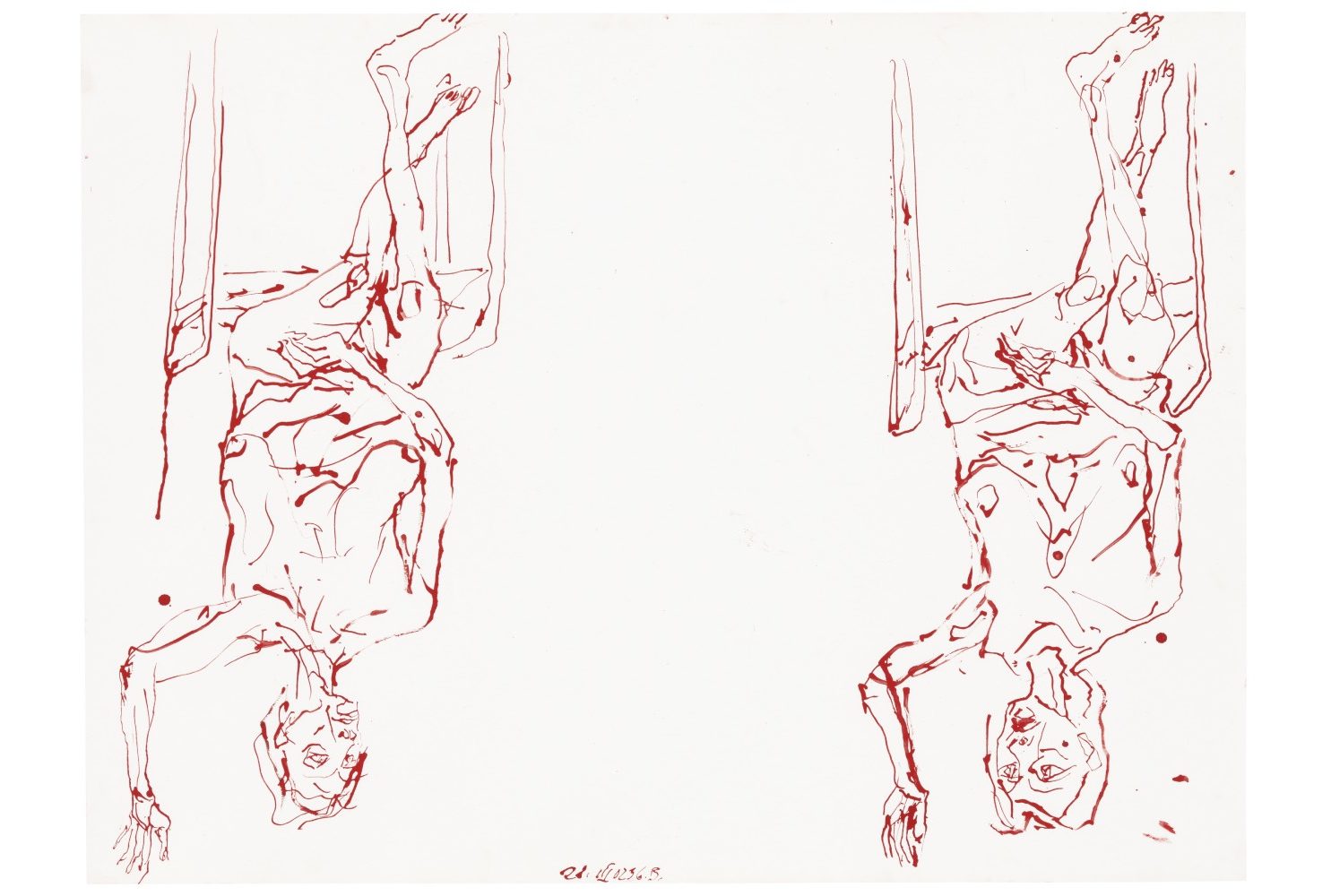

It is hard not to be moved by the works on paper, which at times seem to gesture farewell to the viewer. In Untitled, two figures raise their hands, their aged bodies intimately connected to the application of red ink. These performative serial drawings have a way of connecting in a more immediate way than the larger works in the exhibition. The ease and enjoyment of their making is easily readable. Could it be that Baselitz’s sins are sins of pleasure?

Was ist das (What’s That) conflates the figurative and its materiality in an impressively baffling manner. Nylon stockings are stretched across the canvas, enveloping the legs of a larger-than-life figure. How is this possible? Only because of the materials. Marie-Therese in Dinard (Marie-Therese in Dinard) seems to reference another influence on the artist, the young mistress of Pablo Picasso, Marie-Therese Walter. Such references position the work in another light.

Baselitz’s confessions have often sparked controversy. In 2012, he told the German newspaper Der Spiegel that women don’t paint well, exclaiming, “Oh God! Women simply don’t pass the test,” referring specifically to his overtly warped understanding of value and an unforgivable arrogance around the power dynamics of the market he has so massively benefited from.

For all of the material seduction folded into these works and the decadence of their impressive curation within the immaculate Bermondsey space, these paintings seem out of time, or, more precisely, belonging to another time, to the canon of twentieth-century expressive figurative painting that was so aggressively occupied by sexist white men who held views consistent with Baselitz’s troubling oral confessions.