Succes in the YBAs era was undeniably tied to the scandals caused by their exhibitions. However, for artists of the next generation, such as Chloe Wise, recognition can’t be achieved without a flawless mastery of social networks – particularly Instagram (until it gets replaced by another Silicon Valley monster creation). While the notion might sound trite, it’s undeniable that some artists use this platform better than others, and Chloe Wise is certainly one of them. In 2014, she captivated audiences with her series of handbags adorned with luxury brand logos, blending faux urethane pastries with various materials of both plant and animal origin. The highlight of the project was the presentation of her Chanel handbag crafted from faux waffles during the brand’s official fashion show. Her spectacular sculptures were part of a wider exploration into the plastic and aesthetic potential of food. Additionally, her large-scale portraits of friends and family posing with everyday food items – such as fruit, milk cartons and packets of butter – also date to this period, reinventing the genre of still life, “food porn,” and portraiture.

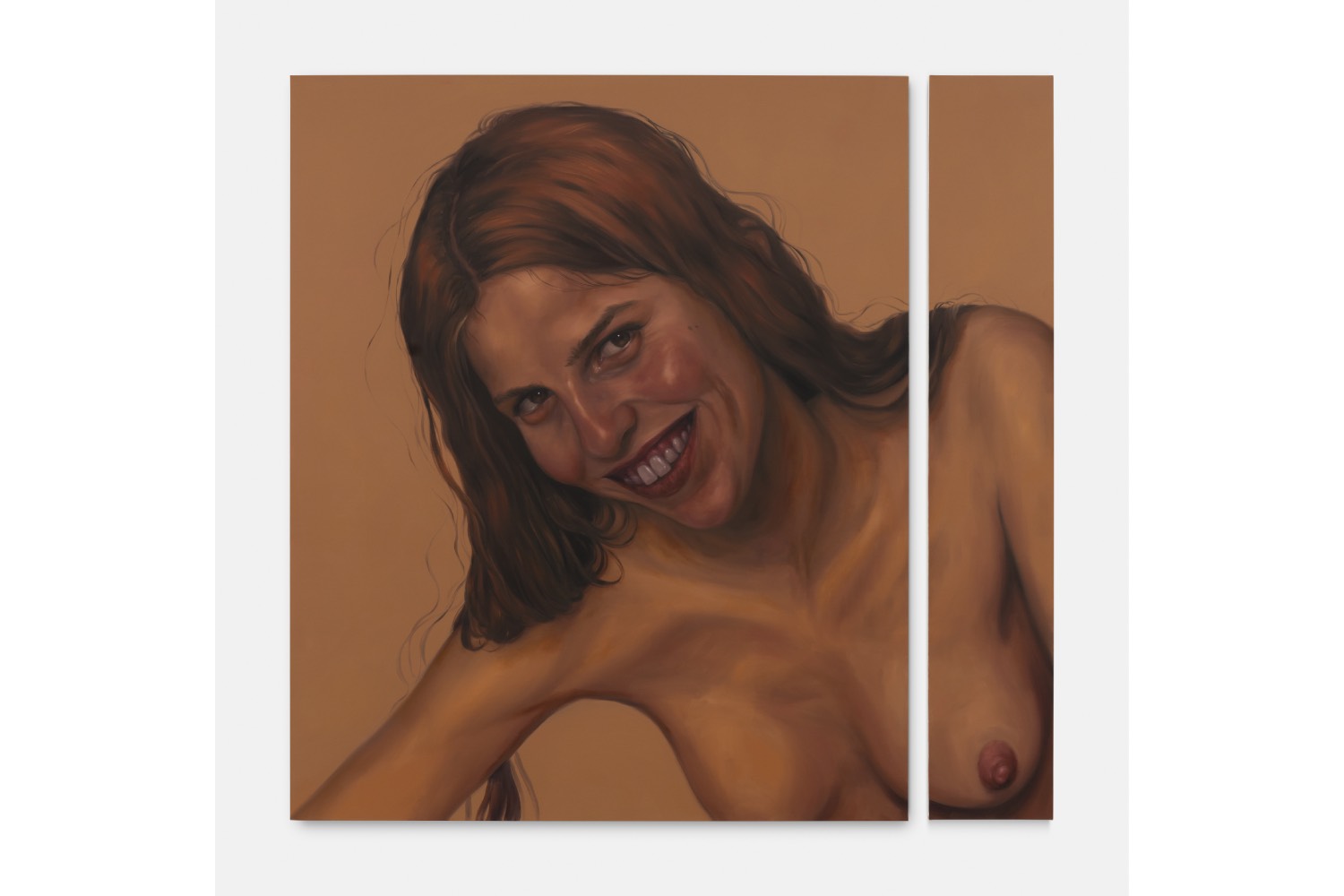

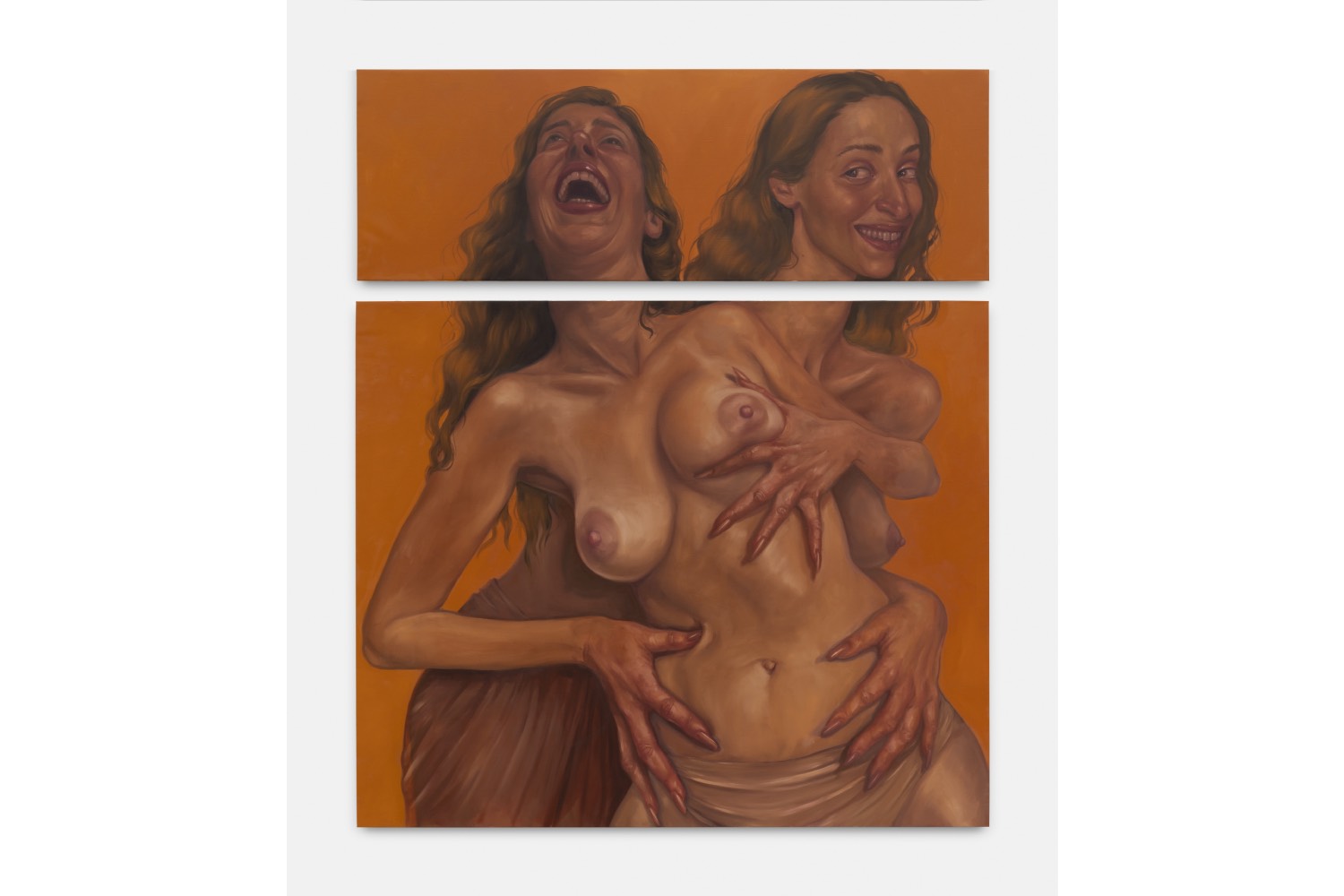

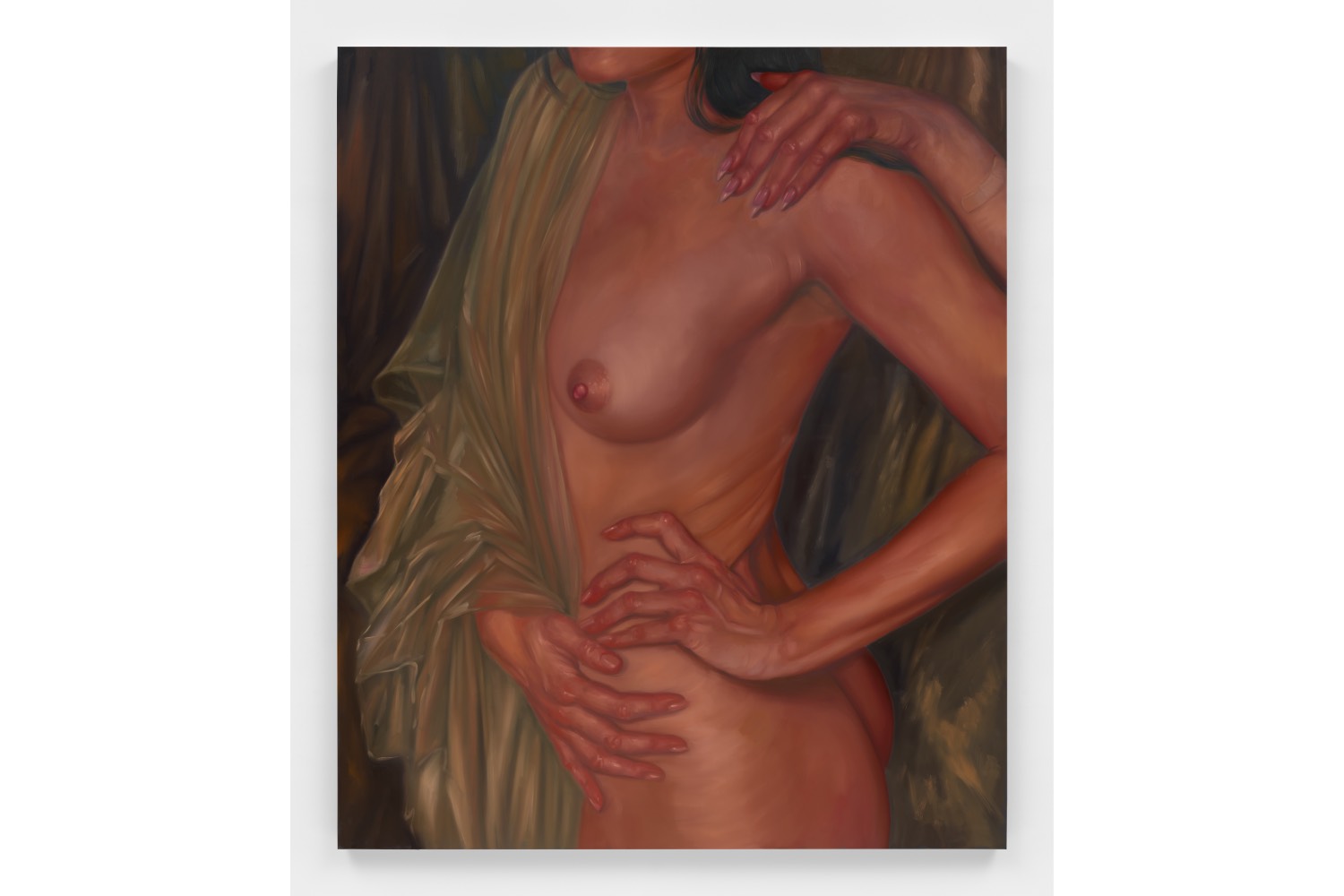

Her latest exhibition, “Torn Clean,” at the Almine Rech in Brussels, hones in on the latter aspect. For this new serie of works, Wise emplys a highly restrained, almost monochrome color palette centered around flesh tones. These portraits depict women who, much like in her previous series, are drawn from her imeddiate circle. Some are completely naked, while others are scantily clad, yet it’s the faces rather than the body that is the main subject here – even when they’re not directly visible (Dive into each eye and swim, 2024). All the models have a distinctive exagerated smile ; the reference to social networks is obvious: we are reminded of selfies that are unusable, or for which the wrong filter has been applied (Malicious Compliance, 2024). Wise’s choice of titles allows for multiple interpretations, such as Dauntless in the trashed world (2024), a poignant painting in featuring a model with a seemingly elongated neck, in the manner of a Pontormo masterpiecec. Her smile is both spontaneous and feigned – no one could mantain such grin for the entire duration of a pose, particularly in a painting based on a photograph, another nod to Instagram. Thus, this young woman is “dauntless” in a “trashed” world – perhaps indifferent to her portrayal on social media, a realm often characterized as « trashed ».

The title of the exhibition itself is open to various interpretations. Several portraits feature plaster applied to the skin, sometimes subtly, sometimes prominently. While seemingly innocuous, this object carries a strong political charge. Invented by Johnson & Johnson in 1920, it is praised for its adhesive properties and its supposed ability to blen with “skin colour,” making it nearly invisible. However this notion raises some questions : Whose skin color does it truly match ? All recent attempts to market band-aids for black or mixed-race skin have consisently failed. The title might also refer to the swift act of removing a plaster and the debate surrounding it. Fans of Tintin may recall the recurring joke of Captain Haddock struggling to get rid of a plaster passed among passengers on a plane to India. Furthering this reflection, a monumental installation features oversized band-aids made from materials like leather, shearling, latex, rubber or pony hair – highlighting our penchant for technical solutions to protect our skin, while animals rely solely on their own.

Wise’s work not only revisit the aesthetics of art history, particularly in portraiture and still life, but also challenges its formal aspect. Her portraits are often depicts the same model twice, in different poses, with the canvas asymmetrically divided. While traditionally, ditptych or triptych were designed to guide viewers through a narrative, Wise deliberately confounds us withing her own compositions.