Marina Abramović broke yet another barrier last year and became the first woman to have a solo retrospective in the 256-year history of the Royal Academy. The fact that it took more than two and a half centuries for the Royal Academy to recognize a female artist in this capacity is a topic worthy of discussion. This review, however, is about Abramović’s pioneering contributions to the contemporary art world, and how her artistic expression resonates within the current cultural landscape as she now takes over the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam with her entire body of work.

The exhibition presents fifty years of Abramović’s prolific oeuvre, and includes early works created in her homeland, the former Yugoslavia; works from her time in Amsterdam; groundbreaking collaborations with her partner Ulay; and a survey of her subsequent solo career. We witness archival videos, photographs, and installations featuring more than sixty key works, as well as four live re-performances by artists trained at the Marina Abramović Institute.

Abramović helped shepherd performance art from its experimental beginnings into the mainstream; since the 1970s, she has been a prominent figure of the medium, considered one of its most influential founders. Using her body as both subject and medium, she has consistently explored the physical and mental limits of being.

The works here are presented in thematic chapters, not only tracing the development of her career but also providing a broader understanding of performance art and its evolution in a societal context. One of the most striking themes is “Public Participation,” which explores Abramović’s works that create a dynamic relationship between the artist, the artwork, and the viewer, bringing them together in a shared moment. Audience participation is crucial to her performances, and she takes this concept even further with two of her most notable works: Rhythm 0 (1974) and The Artist is Present (2010).

Rhythm 0, arguably her most radical performance to date, staged in Naples in 1974, involves the artist herself with seventy-two objects having the potential to cause “pleasure and pain.” These include a rose, a bottle of wine, a hairbrush, a lipstick, a gun, a bullet, chains, a razor, an array of sharp knives, and more. For six hours, visitors were allowed to do anything with the objects and with the artist. Abramović stated the instructions: “There are seventy-two objects on the table that one can use on me as desired. I’m the object. During this period, I take full responsibility.”

Following this work, Abramović undoubtedly went through a life-changing experience. The performance began passively, but as time went on, the audience turned increasingly violent. They spat on her, ripped her clothes, cut her with a razor, sucked her blood, stuck a knife between her legs, and even loaded a gun with a bullet. Reflecting on this piece she said, “What I learned was that […] if you leave it up to the audience, they can kill you.”1

Thirty-six years later, Marina once again “faced” the audience, but this time with as few elements as possible: two chairs, a table, and herself. In The Artist is Present (2010), staged at MoMA, New York, she locked gazes with more than 1,500 members of the public over the course of seventy-five days.

The documentation of this work is impeccably executed. On one wall is footage of the artist interacting with numerous visitors to MoMA, facing each visitor individually; the opposite wall shows the many faces of the visitors as they gaze at the artist. The intense emotional reactions of the people who sat with the artist betray a fundamental human craving for connection. As German curator Klaus Biesenbach says, “What is art other than revealing human nature?”2 In this configuration the artist acts almost like a mirror, reflecting the essence of the audience. By juxtaposing these two works we see a progression in her evolution: from physical engagement and aggression to moments of stillness and profound spiritual connection.

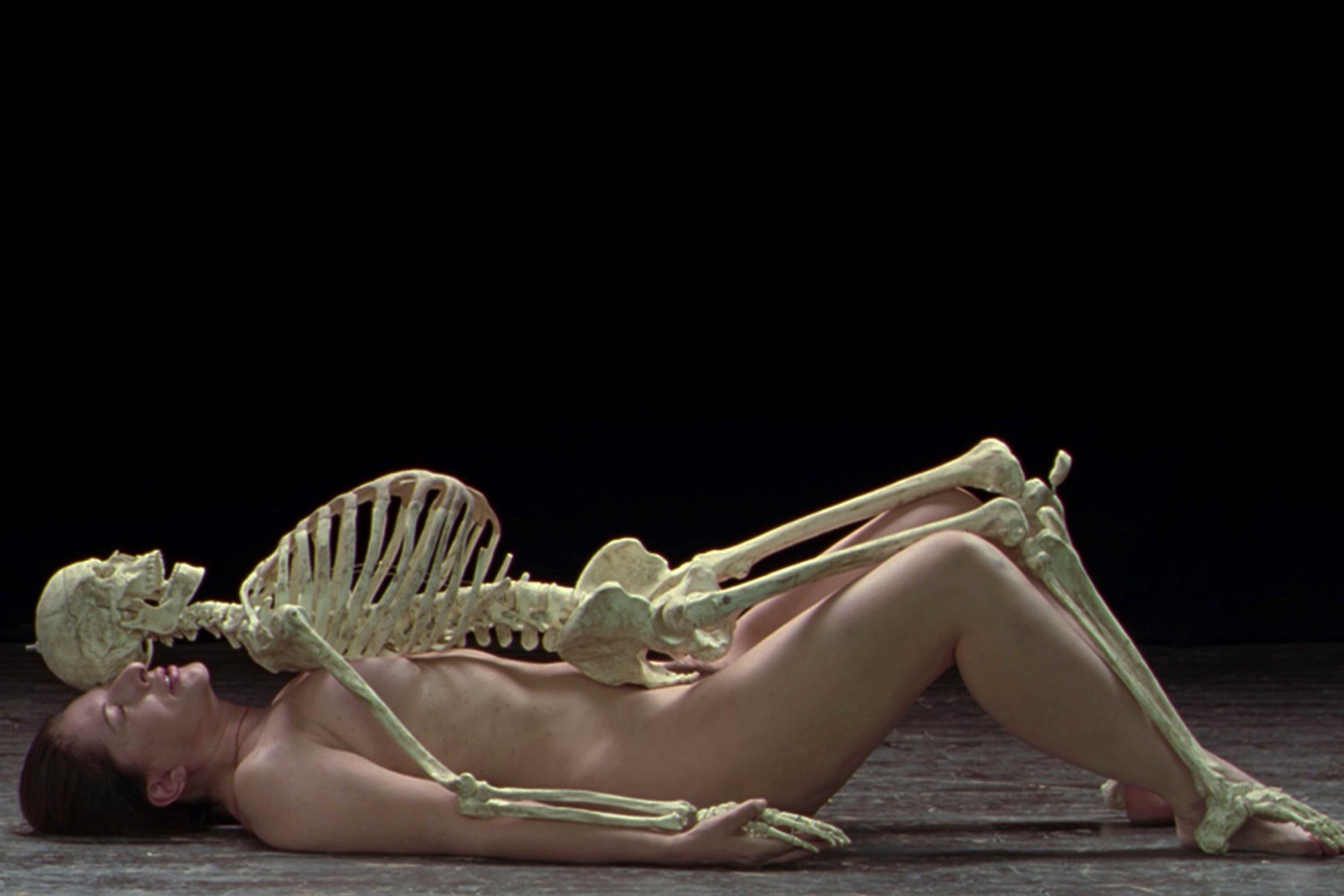

Amsterdam holds a significant place in the artist’s career trajectory. She staged numerous performances in the Netherlands and relocated to Amsterdam in 1976. One notable piece was Lips of Thomas (1975), re-performed for a Dutch TV documentary, in which she uses a razorblade to carve a star on her stomach, then lays bleeding on ice blocks until the audience intervenes. Through these gestures, she explores “our passive role” in witnessing violence. Her boundary-pushing body art challenges established norms and delves into the intricate link between immanence and transcendence.

With her performance Role Exchange (1976), Abramović caused a stir in the Dutch press. During the performance, she exchanged roles with a red-light district sex worker for four hours, shedding light on societal taboos surrounding women. Despite both individuals using their bodies as primary instruments in their respective occupations, society tends to glorify the role of the artist while looking down upon that of the sex worker. It’s quite likely that a sex worker in the red-light district was earning more money than a female performance artist in the 1970s.

It was during this time that Abramović began collaborating with German artist Ulay, whom she met in Amsterdam. Together, as a duo sharing both their artistic endeavors and personal lives, for twelve years they pushed the boundaries of physical endurance through long-duration performances.

Their collaborative performances, known as “Relation Works,” were created between 1976 and 1980. On multiple giant black-and-white screens, we witness their unconventional pieces: Abramović and Ulay breathing directly into each other’s mouths; slapping each other across the face; repeatedly smacking their nude bodies headlong into pillars; bumping into each other; even jointly holding a bow taut, with its arrow pointed directly at Abramović’s heart. These works push beyond mere physical boundaries, exploring themes of human interaction — partnership, gender, balance, trust, and surrender — and challenging conventional notions of art and intimacy. “We used to feel as if we were three: one woman and one man together generating something we called the third. Our work was the third.”3 Abramović remarks.

To go from one room to another, the audience must walk past a man and a woman standing in a doorway, completely nude, mute, and motionless, maintaining eye contact with each other. It’s a recreation of the duo’s famous Imponderabilia (1977), in which visitors navigated a narrow, intimate space between two naked bodies. A guard and a person in a white lab coat stand on both sides — presumably a precaution after MoMA was sued by a performer earlier this year, accusing the museum of failing to prevent sexual assaults against him while performing this piece during “The Artist Is Present” exhibition fourteen years ago4. To pass through, one must choose whom to face, touch, and interact with. This decision and the viewer’s actions are the performance. Like many of Marina’s pieces, the setup blurs the line between audience and participant.

This notion of “the third” began to emerge with the performance Nightsea Crossing, wherein Marina and Ulay sat motionless at opposite ends of a table. The duo performed this piece twenty-two times worldwide from 1981 to 1987. When Ulay began to face physical challenges, Marina’s resilience became increasingly evident, subtly hinting at the strain within their relationship.

The final performance from the pair was The Lovers: The Great Wall Walk (1988), in which, for three months, they walked toward each other from opposite ends of the Great Wall of China. In the end, this eventual meeting in the middle served as the end of Marina and Ulay’s relationship. However Marina’s vision and eagerness to create carried on. During her journey to the Great Wall of China, she experienced fluctuating energy states, attributed to the diverse minerals in the ground beneath her feet. This awareness gave birth to her “Transitory Objects,” her first body of new work following the split.

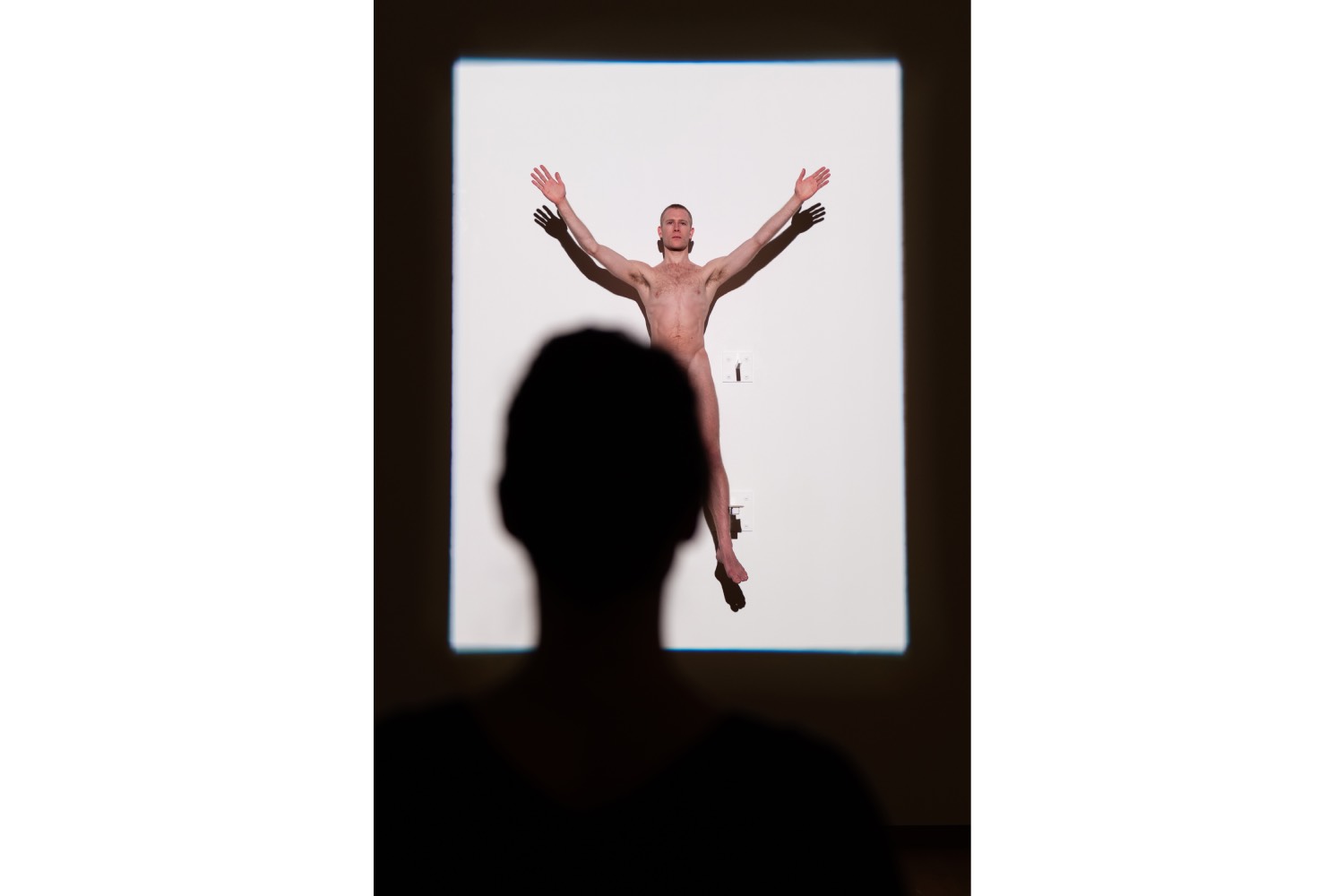

In the exhibition, we enter a room with crystals scattered across the floor. On one wall a video depicts Marina lying on a metal structure/bed with crystals underneath. Visitors can remove their shoes and place their feet inside. While everyone is busy putting their feet onto the “energy filled” stones, there is a performer sitting naked on a bicycle seat, positioned high up on a wall: a reenactment of Marina’s performance Luminosity (1997). Here, energy and physicality become primary materials; nothing else exists. The title of the piece makes sense: a state of “luminosity” appears over the course of the work. Although Marina herself performed this piece for six hours, it can now only be performed for a maximum of thirty minutes, requiring performers to change regularly.

After The Lovers: The Great Wall Walk, durational performances of such magnitude did not reappear in Marina’s body of work for nine years — not until her performance Balkan Baroque in 1997, a four-day, six-hour performance in Venice, in which she sat on a pile of bloody cow bones, attempting to wash the blood off them with a brush, meanwhile singing Balkan songs to mourn the massacres in Yugoslavia. Following this came The House with the Ocean View (2002), an uninterrupted twelve-day-and-night performance at Sean Kelly Gallery in New York. Abramović inhabited three simple cubicles that were hung on the wall, representing a bedroom, living room, and bathroom, separated from the audience by ladders with knives as rungs. During this time, she abided by self-imposed rules that included not eating or speaking and showering three times a day. This remarkable work will be renacted in June at Stedelijk; Abramović says it’s the only performance piece presented in the exhibition without any compromise.

In Abramović’s transcendental practice, in which limitations blur, there exists but one certainty: her active embrace of life itself as an ongoing performance. She embodies the essences of both a conceptual and an intuitive artist. Her exploration of performance art delves into realms of physicality and experience, exploring the limits of human nature and consciousness. One cannot help but wonder what would happen if Rhythm 0 were to be performed today. The artist reflects: “We’re talking a different time. We’re talking political correctness. [There are] so many restrictions on all works now, not just me. Performance artists in the ’70s, not one of their pieces would be possible today. Museums would forbid it. The security would forbid it. There would be a huge riot in the media about how appropriate it was or wasn’t. You know, I am so fed up with the system right now, because artists have to have freedom of expression, and this has been taken from us.”5 Nonetheless, the enduring facets of human nature remain manifest.