Belgian artist Jef Geys’s retrospective exhibition “You don’t see what you think you see” at Wiels, Brussels, is dictated by the artist’s personal archive: a meticulous index, spanning almost sixty years, which numbers, documents, and titles the eight hundred and forty-four artworks that collectively make up his life’s work. The posthumous survey rejects chronology and arbitrary thematics in the presentation of more than two hundred works, offering no fixed route through two floors crowded with Geys’s oeuvre. This miscellany is, however, faithful to the artist’s own ideas about his work. The curation aptly reflects a true lack of hierarchy: ephemera, painting, installation, sculpture, archival documentation, film, and photography are shown cheek-by-jowl.

In 1963, Geys was appointed as a teacher at a children’s school in the small Belgian town of Balen –– a position he maintained for twenty-nine years. His classroom was the site of inception for much of his work, and the influence and importance of pedagogy is omnipresent. Actual “topics,” including youth, counterculture, biology, economics, and politics, were integrated into his works and teachings. No notion was considered too grand or too conceptual for his young students, and the artist would regularly supplement these ideas with objects and expeditions: one week a visit to Marcel Broodthaers’s studio, the next week a work by Lucio Fontana or Joseph Beuys brought to “show and tell.”

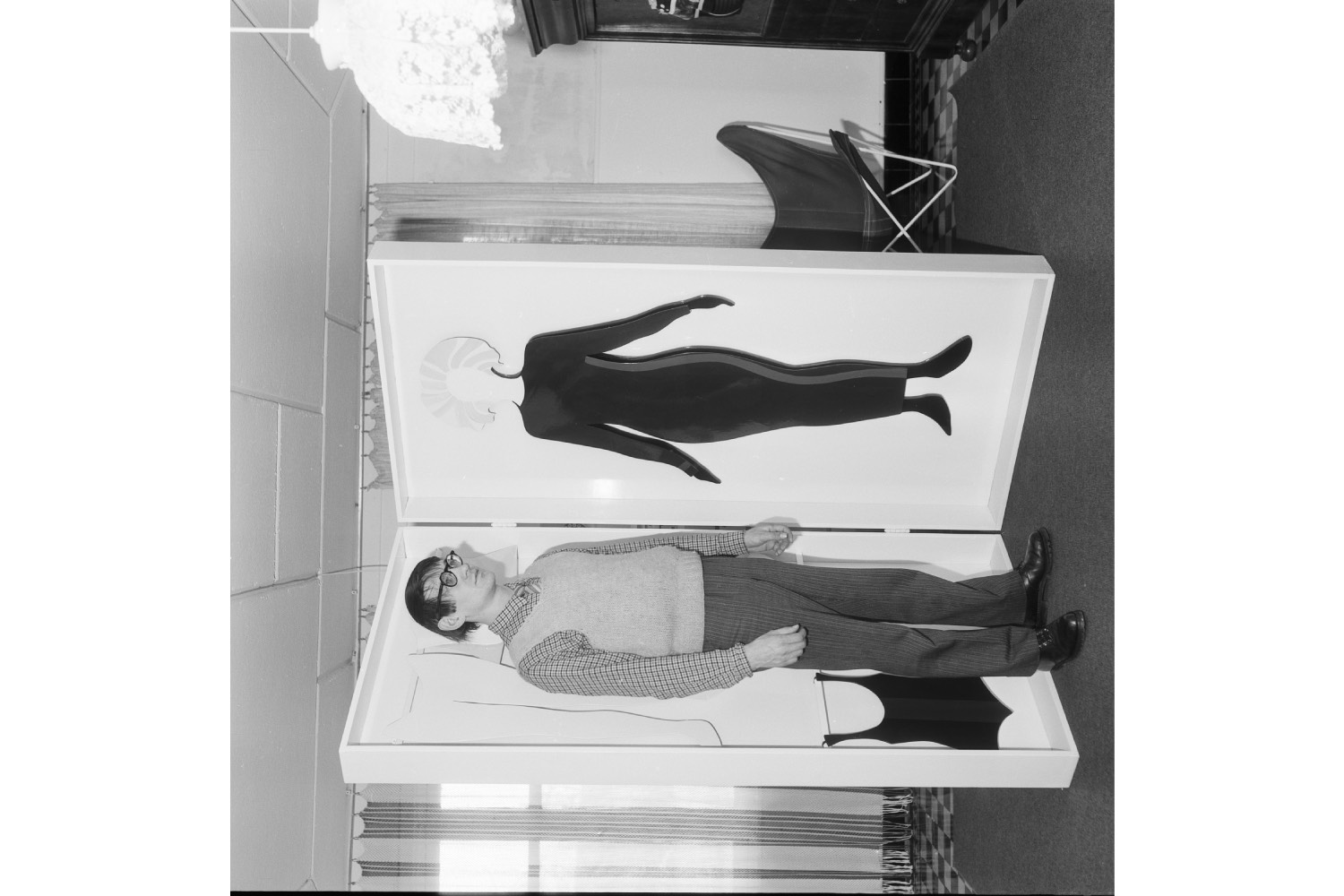

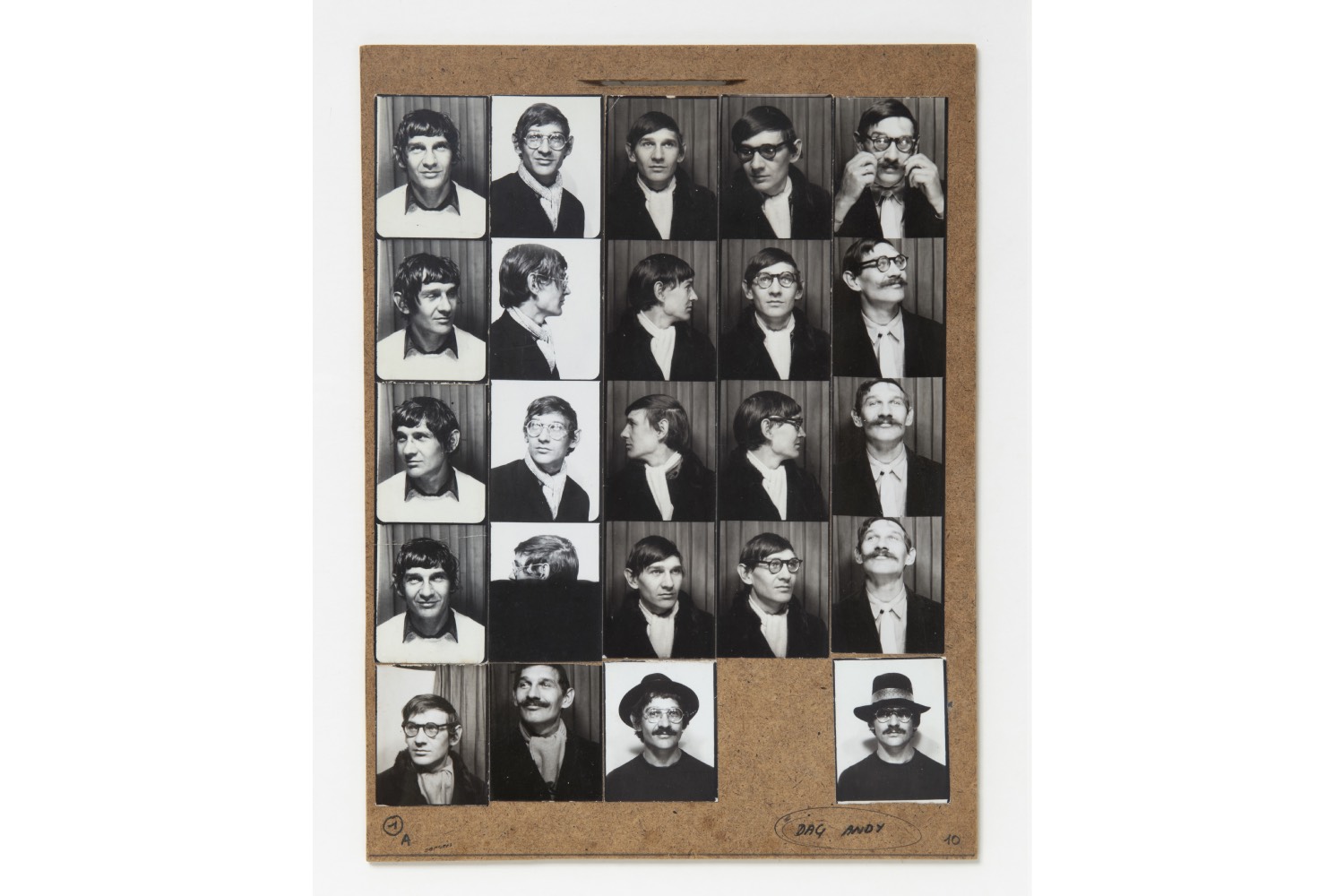

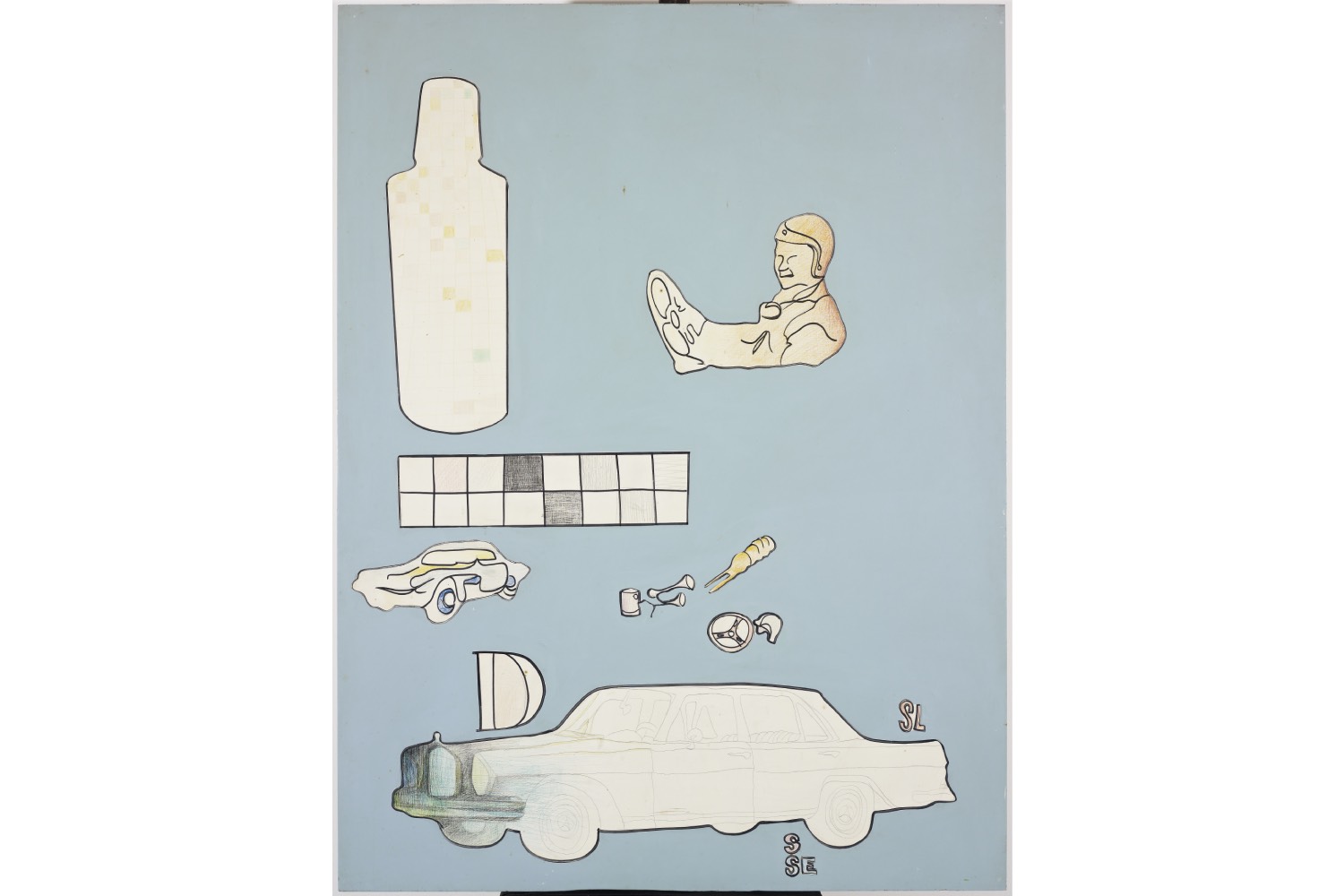

Geys was no doubt an unconventional conceptual artist; he rejected the tropes of European men making concept-based works in the 1960s in favor of his own modes of thinking and questioning. Geys’s genius was his interrogation of societal preconceptions through rudimentary means. Looking at the works at Wiels, one can imagine how this comprehensible and “fun” approach to making and exhibiting might have raised eyebrows among his contemporaries, who relied on well-trodden paths of language, ideology, and academia to ground their work.

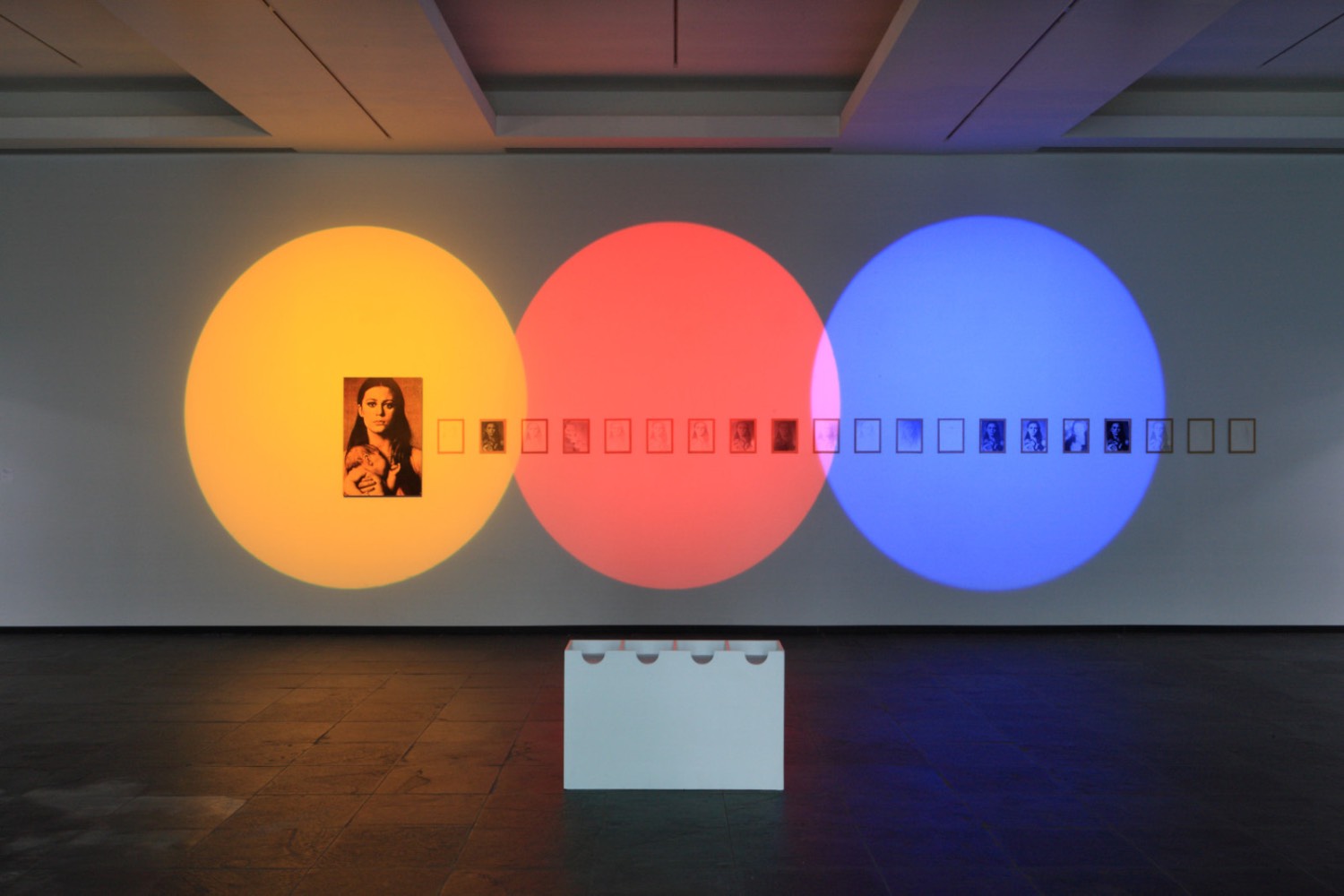

All the Black-and-White Photographs until 1998 (595), shown in full on a single expansive wall of Wiels, is an exhaustive archive of monochrome images lensed by Geys over his lifetime. Didactic and simplified, the individual image is unimportant (and proficient composition is lacking at times), but en masse this work represents an important aspect of Geys’s ideology: the breaking down of hierarchy. Just as all his black-and-white images were considered equal, the act of exhibiting at Documenta 11 (2002) or the São Paulo Bienal (1991) existed on the same plane as the exhibition of Back Wall of My Classroom in Balen (156): an ephemeral collage installation made for his pupils to reflect on art, politics, and current affairs.

he artist’s propensity for hierarchical deconstruction extended to art-world power structures of the time: when, in 1971, Geys was invited to participate in the Bruges Triennial, he proposed: “I’ll rent out my exhibition space. They say: that’s not possible. I say: yes, you choose me as an artist and my artistic project is to rent out my space to people whom you didn’t invite, who were excluded. Because you decide what is in and what is not, what is culture and what is not, and I want to contest that.” Geys’s proposal was ultimately rejected, but the related correspondence, a work in itself titled Triennial Bruges – For Rent (297) (1971), is on view.

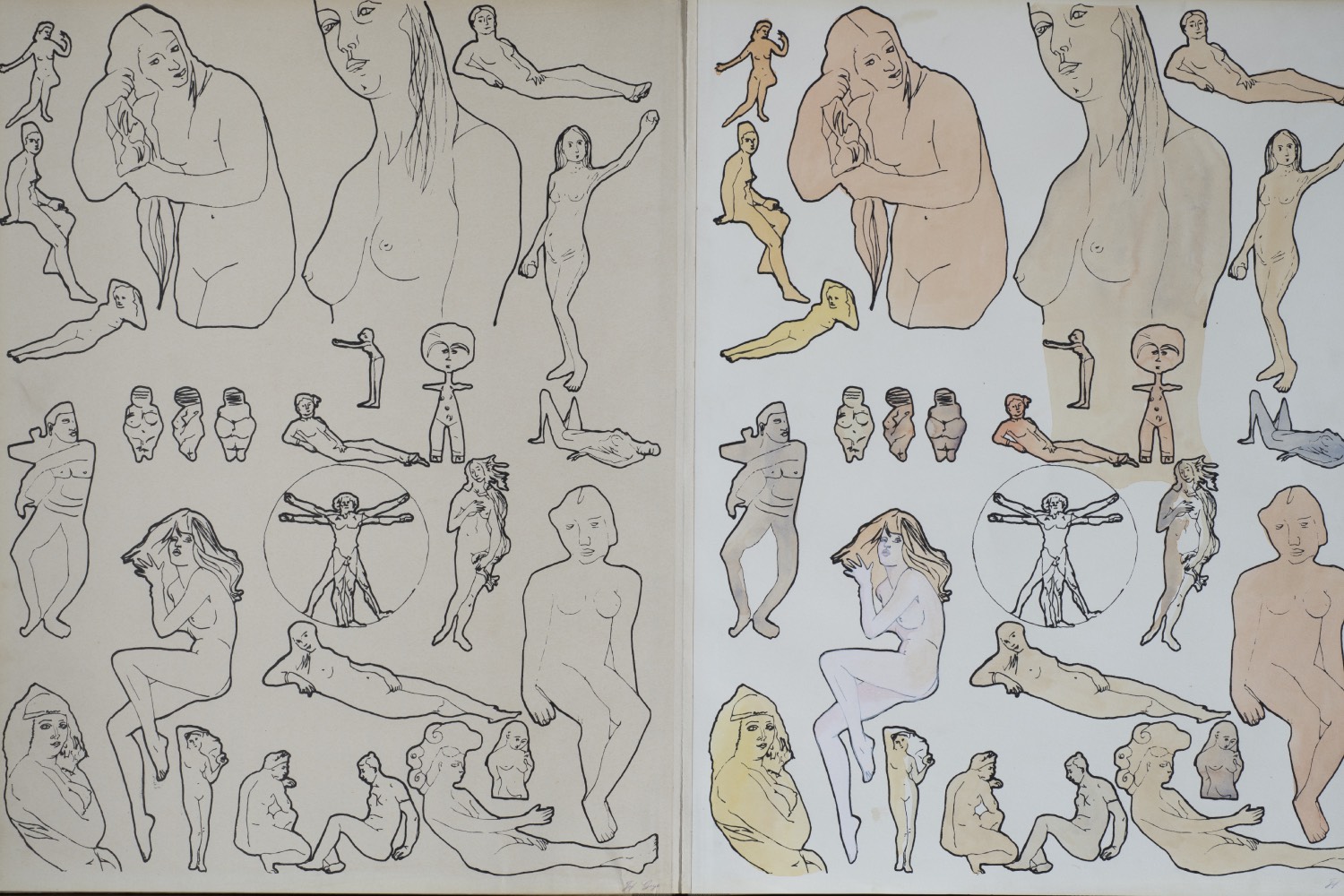

Works in the exhibition are clearly presented within the context of the artist’s worldview. Geys — and by proxy his students — reckoned with the macro (geopolitics, gender roles, capitalism, and power structures) through the micro (a locally distributed newspaper or a dialogue with the women of a Belgian socialist club). The artist’s 1968 work School Playground in Balen – Map of the World (198), shown as photographic documentation, encapsulates these ideas: “I discovered that a certain class had a very limited knowledge of geography. They were unable to situate themselves […] one needs a global insight into the world in which we’re living […] I worked out a plan: together with the pupils we painted a huge map of the world in the playground, 50 × 25 meters […]. In a span of two or three months 90% of the pupils could readily use this map.”

“You don’t see what you think you see” isn’t the monumental retrospective that one might expect from a member of European conceptual art’s first generation — nor should it be. Jef Geys wasn’t an artist who participated in the all-male one-upmanship of the era. Geys’s works are at times modest and throwaway in form but consistently remarkable in conception, favoring process over product. These are not works that are easily applicable to standard modes of art critique; to fully appreciate Geys, the viewer might need to level their own hierarchical playing field, regressing to a child-like condition of unbounded curiosity, unaffected and uninformed by art-world preconceptions.