The Italian feminist thinker Silvia Federici once wrote that “the human body and not the steam engine, and not even the clock, was the first machine developed by capitalism.”1 In “Day Care,” at The Common Guild in Glasgow, Nicole Wermers extends the transformation of individual power into specific types of gendered labor-power — the kinds that go on at night in white-collar spaces, as well as those that go on in the glaring light of day, like childcare.

Wermers’s “Reclining Females” series (2022–24) is positioned at intervals across the glistening modular tiling system of a redundant and real-life white-collar space on the seventh floor of a corporate office building. For the past few years, The Common Guild have been repurposing and occupying spaces like this across Glasgow in lieu of a permanent home. The room is made up of one grand curve, with an exterior wall made entirely from panes of glass. The frames fracture the bright sunlight, creating long, porous shadows that stretch out across Wermers’s large plaster bodies, reclining on cleaning trolleys, laden with all the accouterments of pink-collar work. Federici reminds us that such sexual divisions of labor are power relations. When she talks about “primitive accumulation,” she is talking about the enclosure of land, which began in England in 1604, and with it, the enclosure of bodies — namely, women’s bodies —within certain forms of devalued labor. The accumulation of capital depended on social degradation to which women fell prey.

Much is at stake in “Day Care,” not least the implication of not working, or refusing to work, within a space like this; but also of not cleaning in a Cartesian sense (a mind-over-body supremacy that imposes regular order on its vital functions through “self-mastery”, not least for women as mothers, nurturers and carers). Then there is the implication — and perversion — of a statuary tradition in the “Reclining Females” series. Rather than submit to it as a totality, Wermers calls times on the reclining nude as we know and consume it: she replaces the plinth with a wheeled maintenance trolley, and an ideal neoclassical form in repose with a resting worker who refuses to be alienated from their body.

Federici writes that “primitive accumulation has been, above all, the accumulation of differences, inequalities, hierarchies, divisions, which have alienated workers from each other and even from themselves.”2 In “Reclining Females,” the body refuses to yield to mere function — or object; it is not supine, or alienated, but propped up on its elbows or hip. There is a distinction between raising works off the ground and elevating them; the latter falls prey to the aspirational, perhaps even idolatrous, function of figurative sculpture, while the former merely makes us pay attention. In “Reclining Females,” the trolleys raise the bodies to eye level so that we can look directly at them, and vice versa.

Wermers was born in Germany in 1971 and spends her time between Munich, where she teaches sculpture, and London, where she lives and works. Her practice has long been interested in the vernacular of everyday commodities and a trialectic of products, the body, and the spaces they inhabit. She is perhaps best known for her freestanding “ashtray” sculptures, French Junkies 1–11 (2002), and her Abwaschskulpturen (Dishwashing Sculptures) (2013–17), in which she assembled everyday and domestic objects into dishwasher baskets that fit neatly atop tall white plinths. In 2015, following an exhibition at Herald Street titled “Infrastruktur,” in which she clad modernist chairs in fur coats, Wermers was nominated for the Turner Prize.

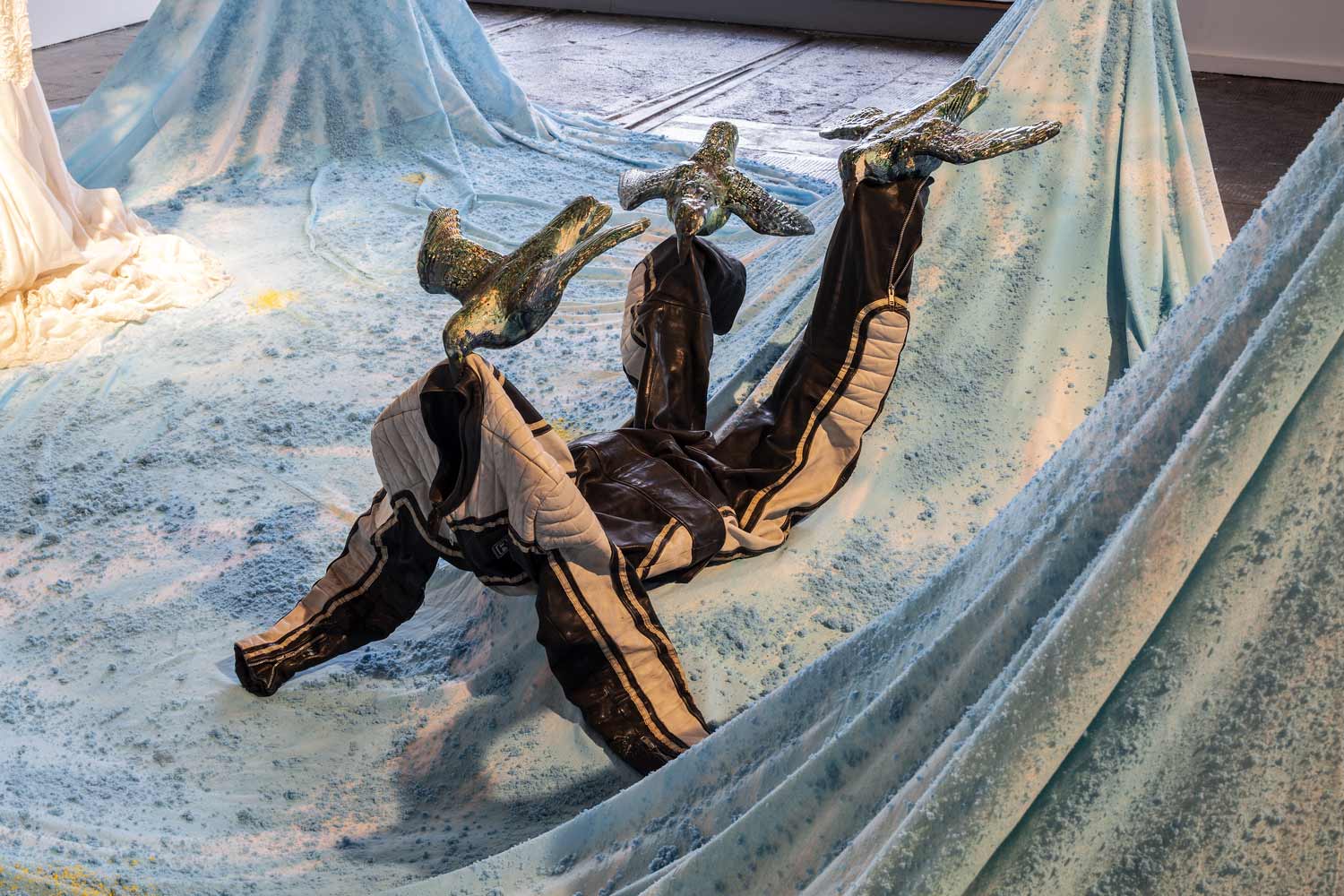

Beyond the formal language of modernism and its implications for everyday commodities, Wermers is interested in the labor force behind them. As far back as 2002, Wermers was constructing modernist freestanding ashtrays — such as French Junkies #9 (2002) — that alluded to the white-collar workplaces of call centers and customer-service desks. In “Day Care” Wermers returns to this motif, replacing the odd floor tile at the Common Guild with piles of sand and cigarette butts, again referencing the congregational smoking that happens outside offices. Within all these works is the notion of a body in absentia — one that leaves its material traces and perhaps its labor in the form of coats, cigarette butts, and dishes. But after a prolonged and enforced period of reclining during the pandemic — which was also a prolonged and enforced period of being with one’s body — Wermers arrived at figuration. For “Reclining Females,” Wermers rejects traditional statuary materials like bronze or marble for the low stakes of styrofoam; not only does this undermine a hierarchy of fine-art materials, but it enables Wermers to render these bodies larger than life, which is important in the context of unseen or rarely acknowledged labor. Using a small saw or Stanley knife, Wermers roughly fashions the lightweight foam-like matter into bodies before daubing it by hand with plaster so that it takes on a masticated quality, as if accumulating the effervescence of soap suds or the toxic erosion of bleach.

The 1:1 ratio of body to plinth — or trolley with its plaster-daubed hardboard top — gives airtime to the production process, not only that of the working subject but also the artist. Wermers assembles the vernacular of domestic products around these frameworks — a chromatic laundry trolley, a high-tech black model, a vintage brown version with rounded corners. In Reclining Female #7 (2024), she modifies a 1970s maintenance cart by adding little pink curtains, stacks of fresh towels, particular makes and models of carrier bags (which she fastidiously sources from Tesco, Co-Op, and Marks & Spencer), and a pink feather duster. In doing so she formulates an aesthetics that is tied together by the repetition of products and shot through with color — a strangely delectable yet noxious bubblegum pink and a heavily synthetic lavender purple. We mindlessly consume these objects daily, but within the context of the gallery they assume an aesthetic quality and value that implicates us, the viewer, in commodity culture. We fall for their enduring appeal before being confronted by their social function.

The central conceit of the show is the way that the curvature of the white-collar office space, the reclining bodies that occupy it, and the crest of the hills in the distance all mirror one another. None of it is working, or working vertically; the entire thing is in repose, while confronting us with the machinations of labor.