There is always a feeling of reverence when experiencing an environment conceived many years before — especially when the artist is no longer present and unable to rethink, reinstall, and readjust the work for the present day. Context, lighting, spatial elements: perhaps they would want to add something to the installation if they were here today. Personally, I always wonder what that might be.

Three out of ten artists in the exhibition “Inside Other Spaces” were able to revisit their work, and I felt privileged to be able to hear them speak about this process during the press conference. Interestingly, Tania Mouraud, Marta Minujín, and Judy Chicago all made contemporary changes to their “other spaces.”

The exhibition presents a unique opportunity to explore the pioneering works of women artists during a period that was transformative in every field of cultural history. In music, we need only think of Doris Day’s “Que Sera, Sera (Whatever Will Be Will Be)” and Elvis Presley’s single “Heartbreak Hotel” in 1956, and “The Great Pretender” by the Platters released the year before. Ten years later we had the Beatles, the Beach Boys, and the Rolling Stones. Then, in 1976, the whole world sang “Hotel California.”

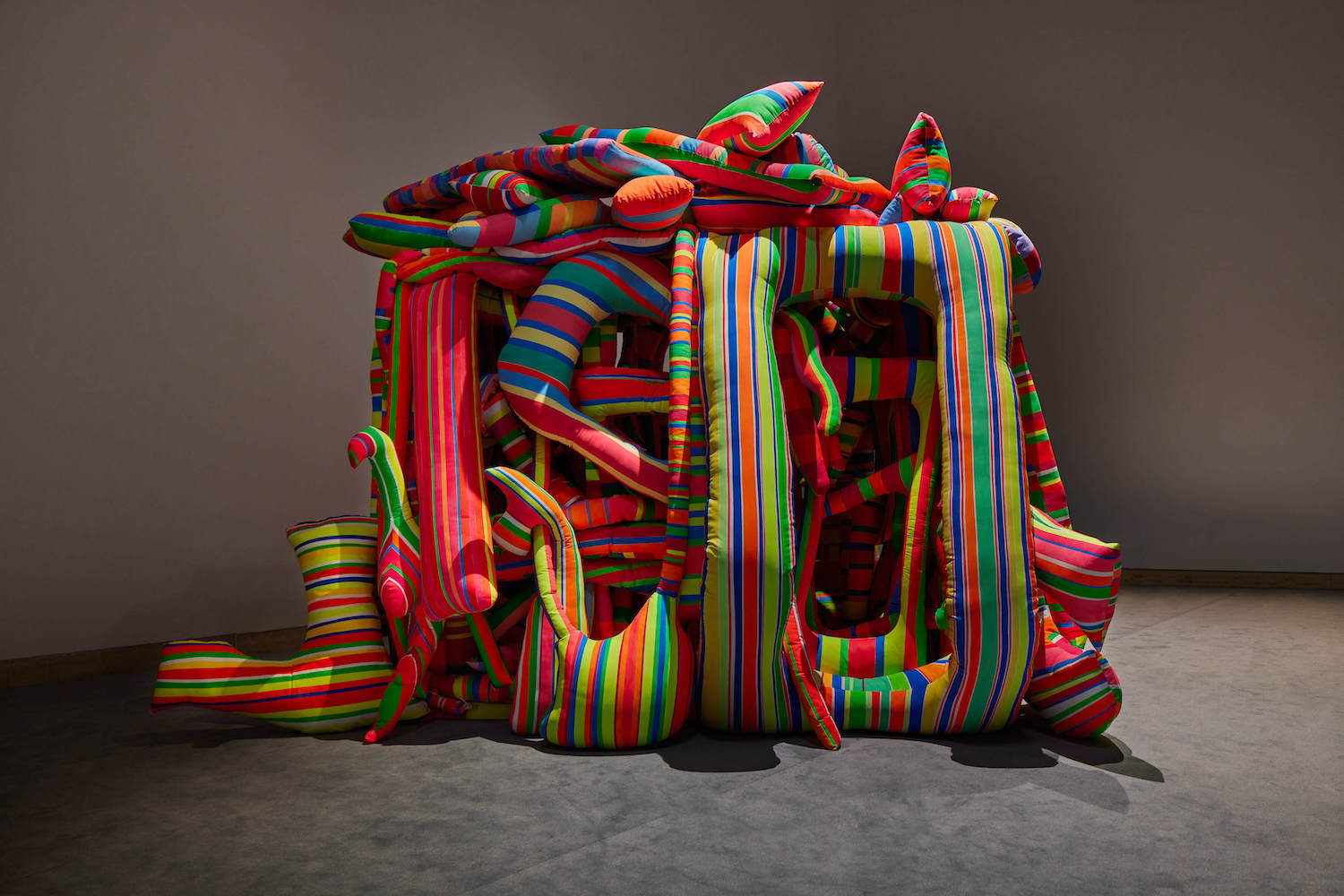

Focused on the concept of environments, “Inside Other Spaces” delves into the ways that women artists challenged traditional art forms and redefined the concept of space in their creative practices. The exhibition brings together a diverse range of artworks spanning two decades — works that interrogate gender dynamics, sexuality, cultural identity, and the relationship between art and the environment. By creating immersive installations, sculptures, and experimental artworks — many of them significant in the context of feminist art history — these women artists not only challenged societal norms but also paved the way for future generations of artists.

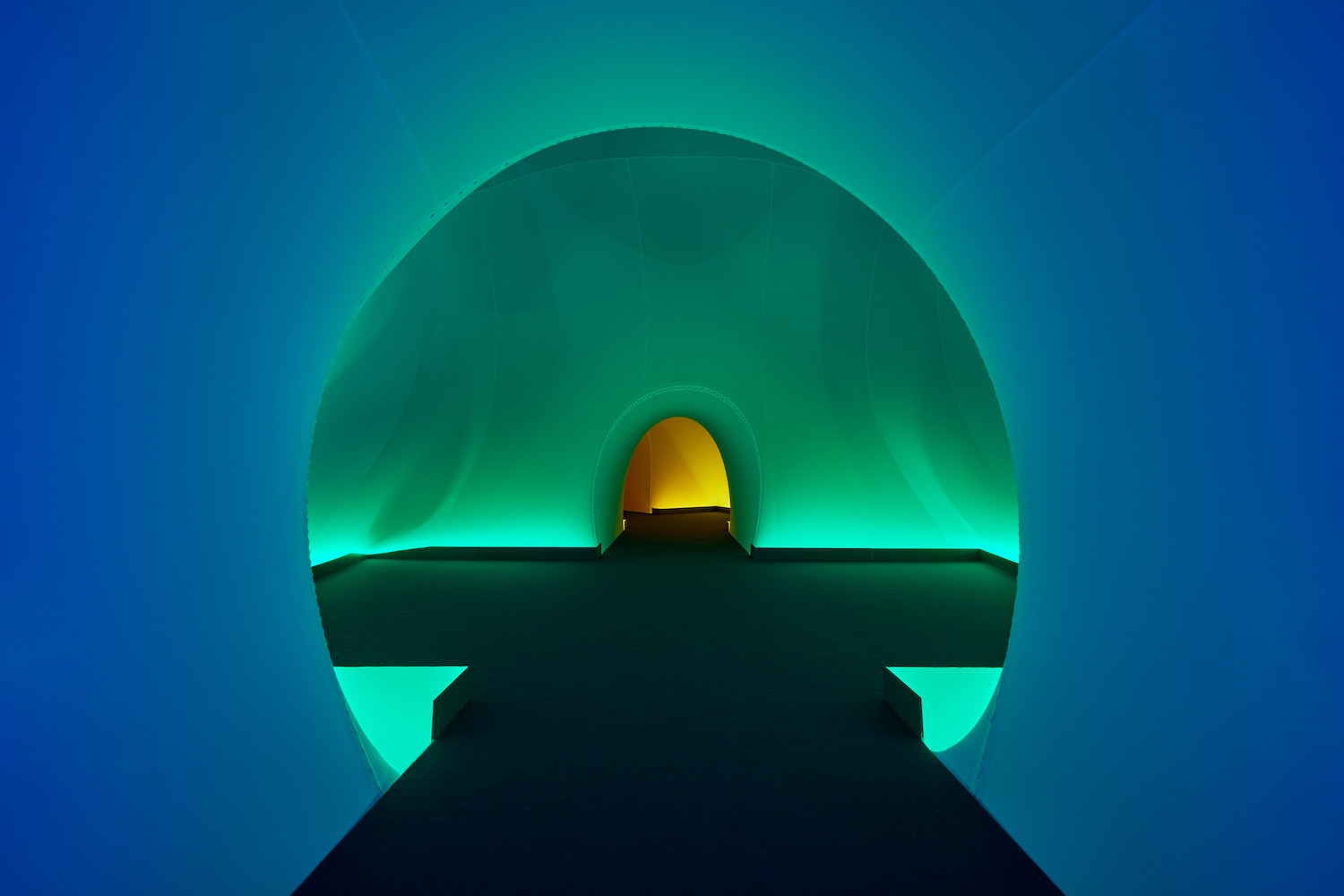

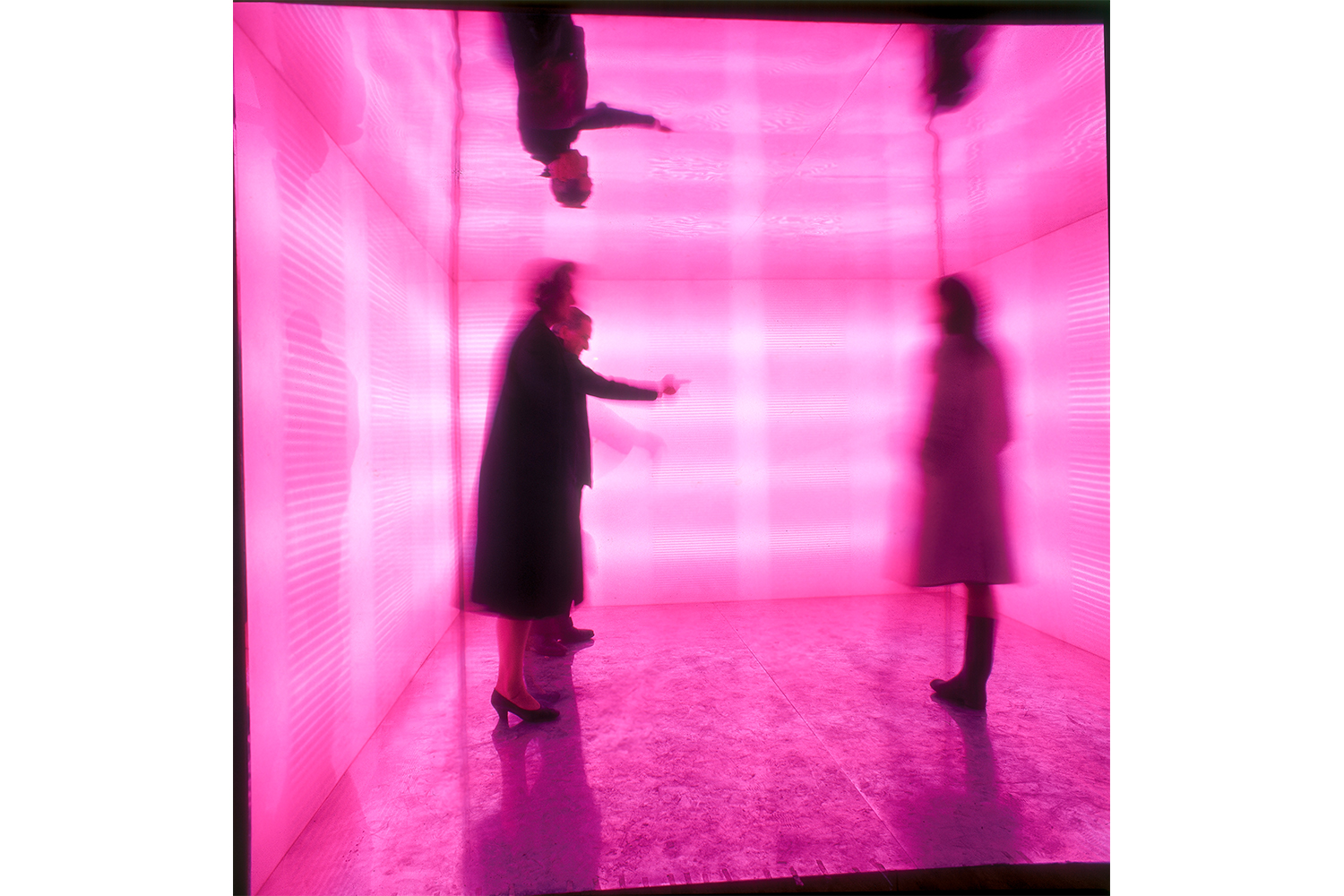

One of the most notable strengths of the exhibition is its curatorial vision, which foregrounds the works of artists who have often been marginalized or overlooked in art-historical discourse. By focusing exclusively on women artists from 1956 to 1976, the exhibition provides a concentrated exploration of their contributions to the development of environmental and relational art. Curators Andrea Lissoni and Marina Pugliese explained that they specifically wanted to show only actual environments that the public could enter and physically explore. This embodied approach allows viewers to better understand the specific challenges faced by women artists during this period and the innovative ways they tackled them through formal exploration. Judy Chicago, speaking about her Feather Room (1966), said that her biggest desire was to make a soft, feminine, cocooned environment. Thousands of chicken feathers are heaped on the floor, which visitors can walk upon or immerse themselves within. Tania Mouraud explained that her work We Used To Know (1970–2023) was initially closed to the public when she first conceived it. This time she opened it up, making it even more provocative to whomever might enter. Inside, a perimeter of spotlights brightly illuminate a room’s interior, where the spectator is forced to confront a mysterious metal column.

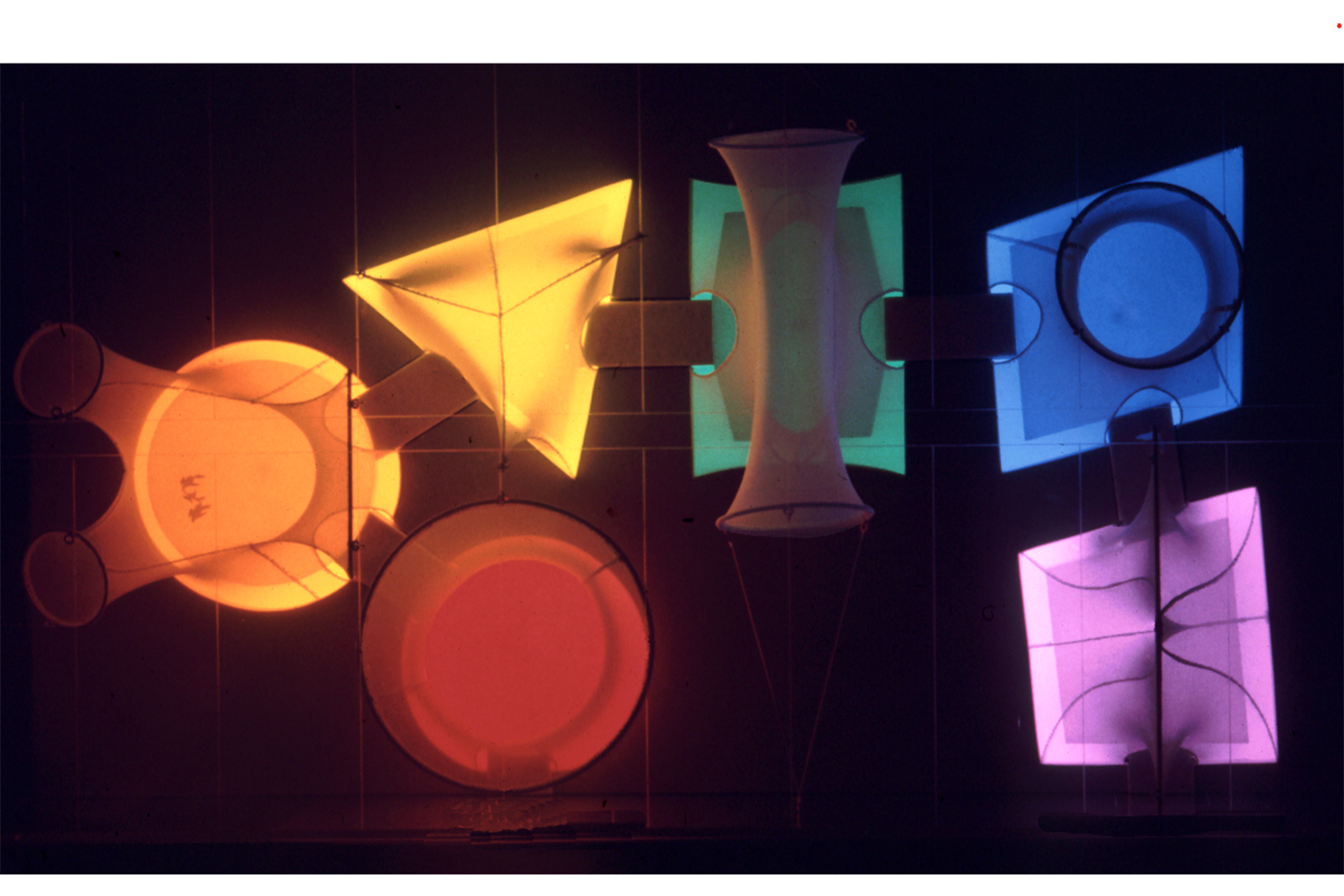

Another strength of the exhibition lies in the range of artistic mediums represented. From Lea Lublin’s immersive installations to Lygia Clark’s performative sculptures, a wide variety of expression is showcased. By encompassing sculpture, installation, performance, and video art, the curators effectively highlight the versatility and ingenuity of women artists working within the environmental art genre.

The exhibition also successfully conveys the political and social context in which these women artists were working. By creating immersive installations that addressed issues of gender, identity, and ecology, they challenged the status quo and interrogated the boundaries of art itself. This socio-political dimension adds depth and significance to the artworks on display, making the exhibition an important addendum to mid-to-late-twentieth-century art history.

The exhibition successfully sheds light on a range of key themes within the genres of environmental and feminist art: gender, empathy, the importance of psychology, patriarchy, and sexuality. By highlighting this pivotal period in history, the exhibition challenges traditional narratives and emphasizes the resilience and innovation of these visionary women. The three years of research and archival work that the curators undertook was instrumental to the show’s success; notably, each reconstructed space was as faithful as possible to its original incarnation. By celebrating these groundbreaking women artists, the exhibition invites viewers to reassess their own understanding of space, gender, and art.