“The Academy is too large and too vulgar. Whenever I have gone there, there have either been so many people that I have not been able to see the pictures, which was dreadful, or so many pictures that I have not been able to see the people, which was worse.” — The Picture of Dorian Gray

She stops in the middle of the Broad Walk and thinks. She pinches her lips like a culinary maestro blessing a scrumptious new creation. And then it comes to her. Mid-pose, she announces, “But, darling, you must always accessorize!” Then she sweeps away, slim ankles wobbling in Balenciaga Knife pumps but otherwise regal enough with two finance bro floozies in tow — a skinhead Madonna flanked by adoring saints in almost-matching navy Zegna suits, VIP lanyards drooping from their necks like sacramental medallions. She’s probably not a curator; she’s almost certainly not an artist. Perhaps she’s of the bureaucratic legions who make the art market move: a dealer, a publicist, an adviser, a consultant still just about bronzed from a summer aboard some ill-gotten yacht, now in a copper London autumn rusting in a fine film of wet.

We were promised a heatwave. The previous Thursday night, at Marina Xenofontos and Tamara Henderson’s opening at Camden Arts Centre, a gaggle of fretful gallery assistants had assembled in the smoking area, worry engraved on their cheeks, hollowed by the strain of installing booths all day. Frieze’s huge twentieth edition would be hellish, they whispered; the annual agony of suit choices, made to endure standing all day and partying all night, the tags delicately removed so they could be reattached and returned, doomed to ruin by torrential sweat; the weather apps said blistering blue skies. This wasn’t to be. It was clear but cold out.

Even unblazed, London in 2023 has an apocalyptic feel: a crumbling public realm, failing services, widespread cynicism, served with oily English cruelty. Surely even collectors, flush with excitement and throbbing with money, could see how this was reflected in many of the works. Not everything was like that, of course. Nor was it even a dominant trend across all one hundred and seventy-five or so galleries. It’s just one theme that you could find even if you weren’t looking for it.

There were, of course, a lot of paintings. They always sell well. Some of them even seemed celebratory — and thus as far from Armageddon as you could get — without it being easy to place how or why or about what, a contrast to the restless swirls on unprimed canvases that were everywhere last year. The sheer amount of it was apparent as soon as you arrived at either entrance: the creeping ambiguity of Sophie von Hellermann’s washed out carnival scenes at Pilar Corrias from one door; the messy, perhaps even ill-disciplined sprays of verdure in Damien Hirst’s “The Secret Gardens Paintings” (2023) at Gagosian at the other.

There were, nevertheless, two main apocalypse-adjacent themes at Frieze London 2023, visible in mega-galleries and emerging spaces alike.

One was opaque sculptures that are openly ominous. Josh Smith’s blackly humorous Little Friend (2023) at David Zwirner, a bronze grim reaper confronting the viewer with open arms, almost offering an embrace rather than a one-way ticket to the underworld, is the most obvious example of that. Another, Nicholas Pope’s The Hole Family (2023) at the Sunday Painter, maintains that feeling with a different expressive range, showing us a thirty-two-strong throng of unsteady-looking figures, almost hollowed of all content but still recognizably human, made of black stoneware clay and meant to represent the various members of his family in different psychological states. Barbara Chase-Riboud at Hauser & Wirth, however, gives this mood a touch of curious allure. The three examples of the artist’s series “Standing Black Women of Venice” (1969–2020) consist of four vertically stacked obelisks referencing ancient Greek and Sanskrit poets, their surfaces shimmering with oracular promise.

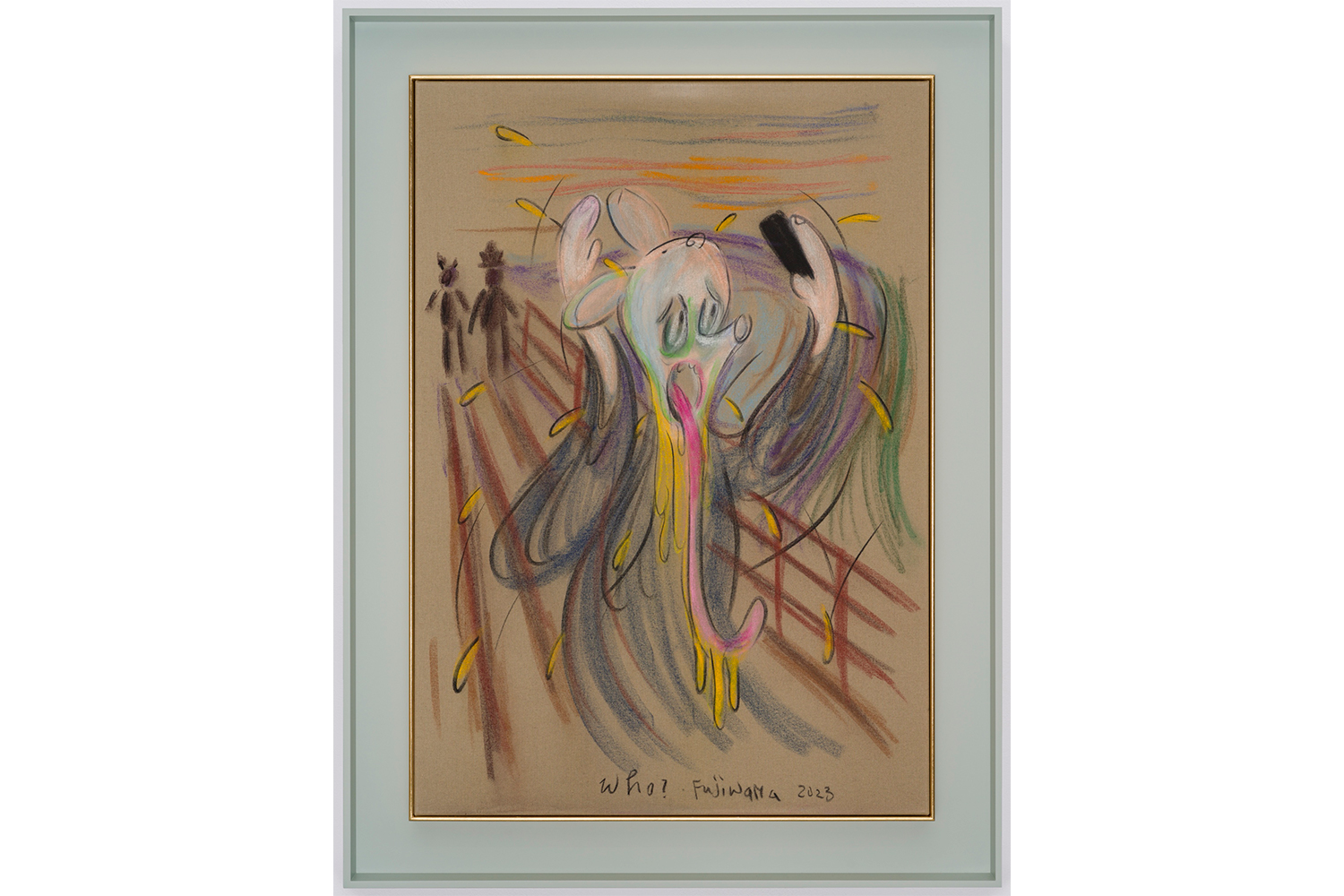

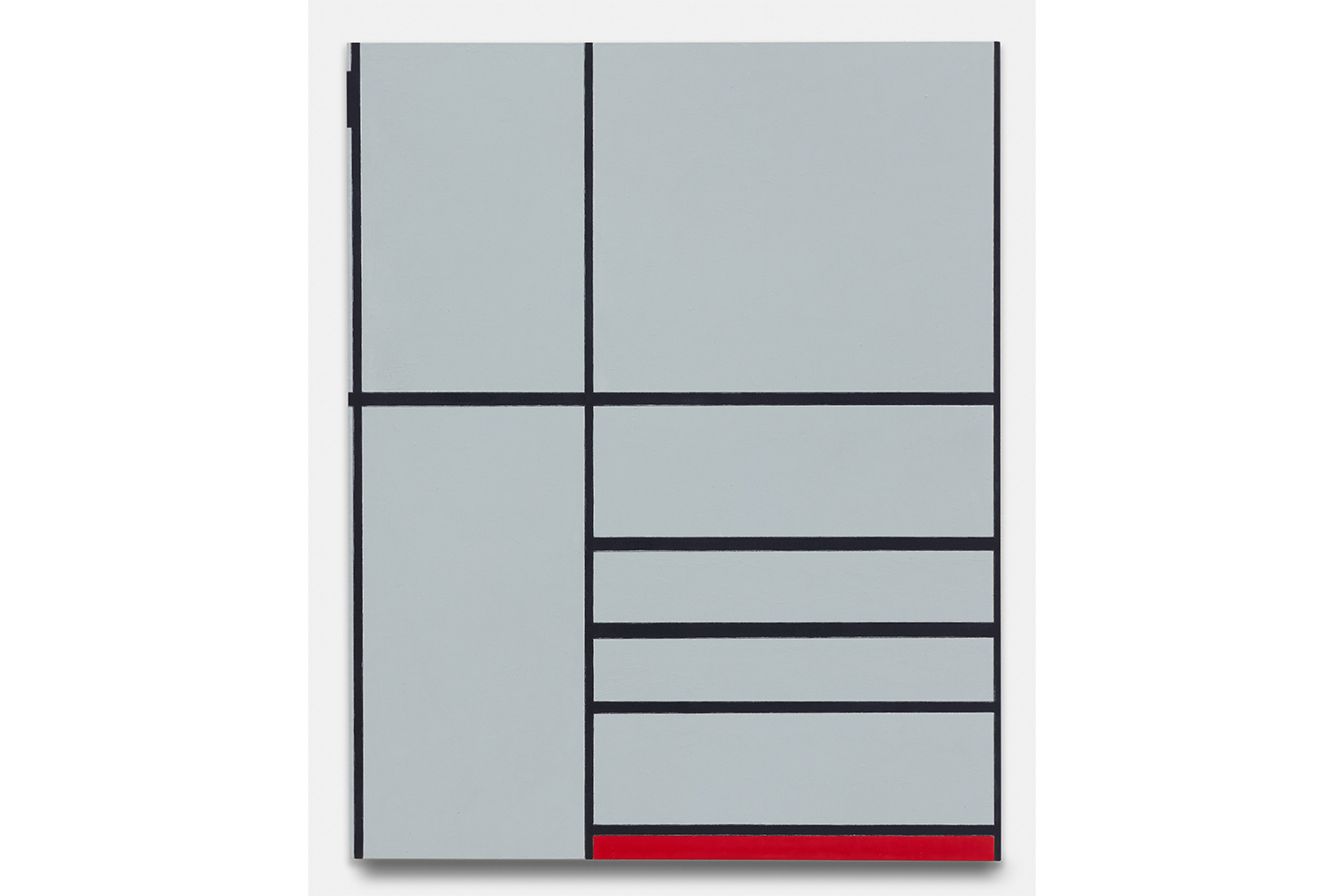

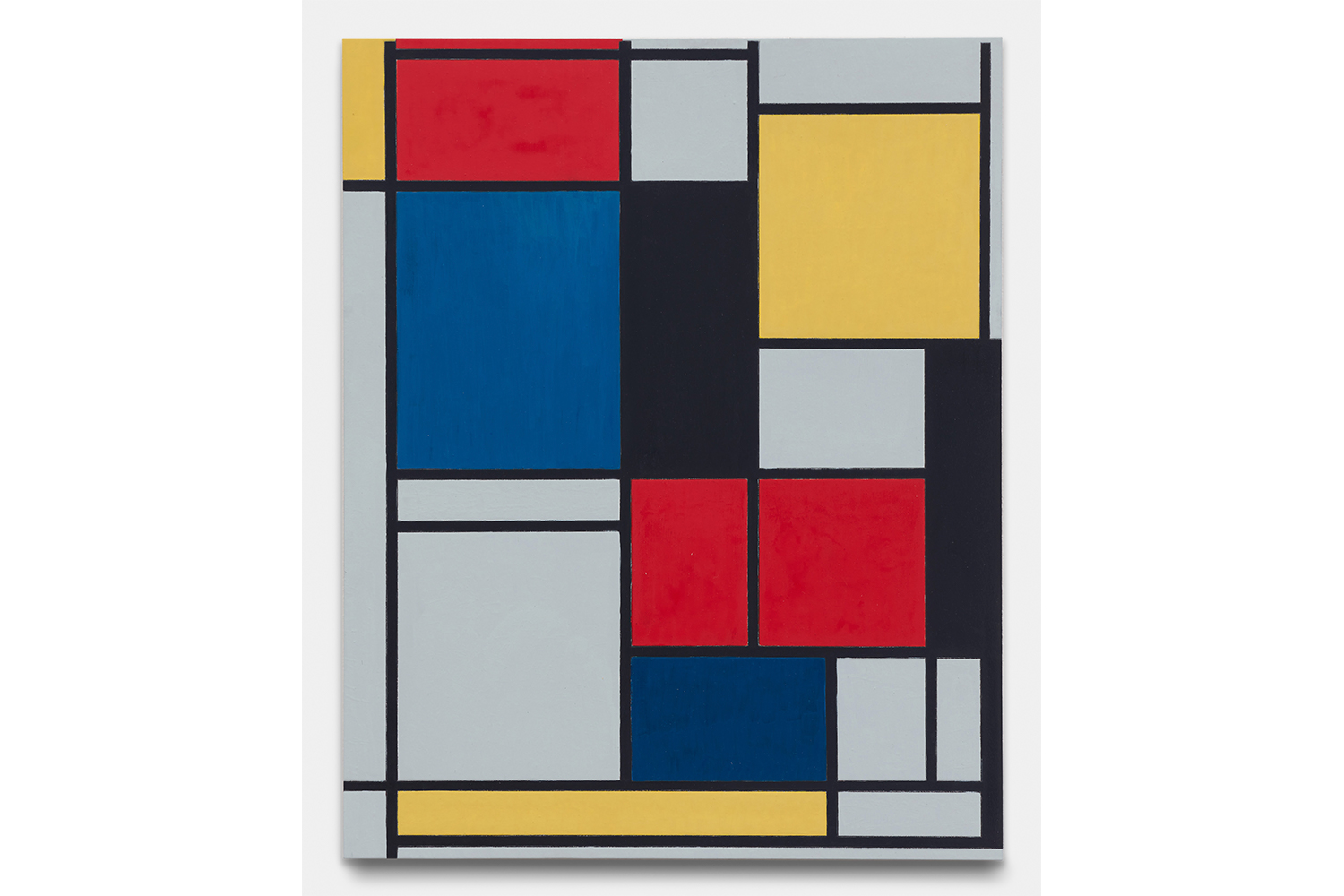

The other theme was paintings that hide in the history of modernism. At least two artists did this very directly. Simon Fujiwara’s Who’s a Mother? (Screamer) (2023) at Taro Nasu, for example, reimagines Edvard Munch’s The Scream (1893) as a frantic canine creature with a huge lolling tongue, drooling and sweating murky yellow blobs, taking a selfie. Meanwhile, Sherrie Levine’s more subtle but perhaps more deceptive After Piet Mondrian: 2 and After Piet Mondrian: 5 (both 2023) at Xavier Hufkens, as the titles would suggest, continues a move she’s been making for the last forty years in appropriating the rigid forms and feel of Mondrian’s paintings between the 1920s-40s in oil on mahogany. Tom Sachs’s Figurative Tower (2021) at Thaddeus Ropac isn’t a two-dimensional painting but still fits in to this theme. This painterly sculpture consists of recreations of commercial crates used to transport Del Monte canned peaches, Campbell’s tomato juice, Heinz ketchup, Brillo pads, and Kellogg’s Corn Flakes, precisely recreating not only the original boxes but Andy Warhol’s recreation of them in Brillo Boxes (1964); by stacking them one on top of the other, meanwhile, Sachs is referencing Constantin Brancusi’s Oak base (1920).

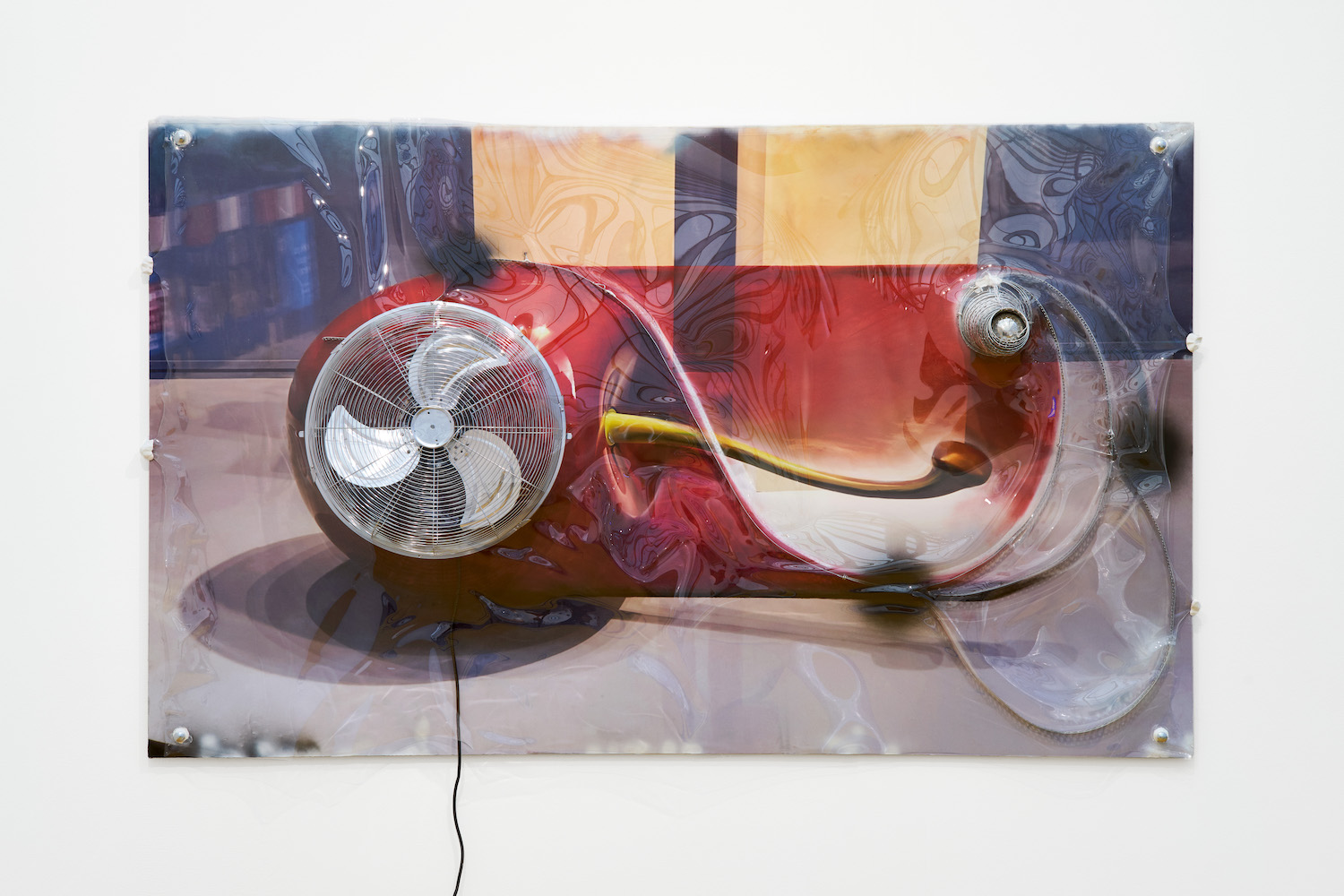

Other cases are less specific, more eclectic in what they borrow from elsewhere. Hugo McCloud’s untitled (2023) at Sean Kelly is a clever, vivid impression of the thing we know as “impressionism,” a welcome alternative to Damien Hirst in oil on tar paper with aluminum foil and coating. At Sprovieri, who shared a booth with Franco Noero this year, Ilya and Emilia Kabakov’s Quotations #1 (2012) invokes a generically fin-de-siecle feel that feels Monetish and Cézanneish, while at the same time breaks up the picture plane with muted blue, pink, peach, apricot, and turquoise suprematist quadrilaterals. Sean Steadman’s whirling architectural waves in Fable (2023) at Project Native Informant, meanwhile, is some previously undiscovered species of “cubo-futuro-constructivism.”

It seems like these two trends — doom and retreat — have intensified what, more than four years ago, I called the “new apocalyptic mode”: the Sex Pistols’ cry of “no future” not as a sneering nihilistic pose but an accurate prediction about what we have to look forward to. Writer Shumon Basar provides a worthy alternative with what he has called “endcore,” a deeply modern experience intensified by a vibe-shift: change keeps changing as cultural acceleration accelerates. The point is less that the future has been “cancelled,” as Franco “Bifo” Berardi put it. Nor is it just that “retro” effects are built into works of art and culture as a stylistic effect that makes them feel “out of time,” per Fredric Jameson’s analysis, or that “formal nostalgia” stops us from thinking or making anything new, which was Mark Fisher’s line.

The point is rather that the two trends dovetail in a form of cultural resignation unique to our own place and time. It is, indeed, significant that Smith’s Little Friend is one of the first things some viewers will have seen as they entered the fair, opposite one of the entrances. Frieze is allegedly about what’s being made and, maybe, who we are right now, if not who we might hope to be. Since that requires being oriented toward the future, it’s at least a little bit ironic that this would appear to us in the form of death. It’s also important that Smith’s reaper has a hollow face. The figure’s infamous hood shrouds an empty space, a nothingness, but says much about how the grim reaper has been transformed into a pasticheable visual cliché with no purchase on our fears.

This reflects the problem with Levine, Steadman, and the Kabakovs’ paintings. There’s nothing technically or conceptually wrong with them, but their appearance here in 2023 seems like part of our entire culture’s ceaseless retreat into the past, an attempt to relive our fantasies about modernism without the suffering and squalor but with the hope and shock of the new somehow still intact. This is, of course, buoyed by the art market. Collectors know these assets are never going to be devalued. They’re doing the same thing as the rest of us: hedging their bets against a future that simply isn’t coming any time soon and that most of us have given up believing in.

By inflecting or openly appropriating not just forms and styles we know and maybe love — or at least by trying to conjure their atmosphere — these works are like a comforting shield from what’s happening now and what we fear might be forthcoming. See also the most concrete instance of this: the installation of Larry Achiampong’s booth at Copperfield, a charming and very engaging attempt to reproduce the feel of the bedroom the artist had as a teenager – even if it doesn’t remake its exact dimensions – that can’t help but fall into this trap.

It’s interesting, then, that the way Sean Steadman’s Fable looks connotes “avant-gardeness” in a way we kind of just know intuitively but without us being able to name exactly what it is. Certain nuances and gestures — those swoops and curves that capture some twirling motion — will be familiar if you’ve seen the source material from over a century ago. It’s not a parody of the avant-garde, but we can read something parodic into it — the sense that not only are parody and pastiche of the classics our only available artistic responses to the present, but a possible parody of that generalized situation of parody.

Something similar is going on in two untitled works by Evgeny Antufiev and Lyubov Nalogina at Emalin: an untitled mosaic (2023) and an untitled bronze vase (2022). If the Kabakovs’ painting says “idealized fin-de-siecle” and Steadman’s “generalized avant-garde,” then Antufiev and Nalogina say “Rome.” It’s probably difficult to read them, then, as anything other than a signal, conscious or unconscious, of the collapse of one empire (the United States of America, also possibly the post-Soviet Russian Federation) that is happening day by day, in real time, before our very eyes, by reflecting on and emulating one of the best known forms of perhaps the most famously and disastrously declining empire in history, to western viewers, at least (Rome). It speaks of a magnificent decadence that is also hinted at in Sophie von Hellermann’s Dance on the Volcano (2023) at Pilar Corrias, which, as the title suggests, shows a diverse group of seven figures with blurry faces and blank expressions, some of their limbs represented by a single fading stroke of color, dancing hand-in-hand around an open hole surrounded by licks of molten fire. This is us.

After all, we come to Frieze — as we do any art fair — not just for the work and the sweet taste of the new and the now. We come to see and to be seen. Gianni Manhattan’s booth this year has a lesson to teach us. It appears that some younger VIP visitors ignored Laurence Sturla’s If not, winter and Written down in rings of grain (both 2023). These two subtle, intricate sculptures are made of overfired ceramic, ceramic slurry, rust, salt, and metal fixings. The arduous process of making them from studio detritus and making them dry, vitrify, and melt, to give them a “fake” weight and history, is rich and detailed. The artist takes a long time — sometimes ten minutes or longer — to explain it to visitors. The young and heedless seem, however, to have been enticed by something else entirely. This was the only booth in the fair that didn’t display anything on the walls. The blank white space then made a perfect vessel to take selfies and upload things to TikTok: fragments of dance routines, cute foot-pops, knowing glares into the cold, indifferent lens.

We also come, of course, for the extracurricular events beyond the fair. That means parties. White wine and smokes on the steps outside Thaddaeus Ropac on Dover Street with Daniel Richter; beers in a car park for Avery Singer (no smoking inside but no drinks outside) in a side street off Savile Row; a crowded bash at the brand new Broadwick Hotel in Soho after CIRCA’s display at Piccadilly Circus; dancing electric before the ragged London skyline at Perrotin’s party way upstairs at the Standard Hotel on the Euston Road; multiple magazine parties on that sodden Wednesday night, including Tank’s twenty-fifth anniversary, Plaster’s launch, and émergent in collaboration with South Parade; Ginny on Frederick’s fabulous celebration of Jack O’Brien winning the Frieze Prize at the Edition Hotel in Fitzrovia; Naomi Campbell blessed us with an appearance at a charity party hosted by White Cube and Valentino, where our skinhead Madonna turned down canapés because she “can’t afford the calories”; a last hurrah at the Asymmetry party at One Marylebone on Friday night.

The lucky clique of super-VIP darlings is shoved in and out of Frieze-branded, chauffeured BMW shuttle cars. The less fortunate surf the Mayfair tide. We dodge delirious parades of art dealers, their center-parted fringes seemingly fixed with strong gel made from the milky tears of some troubled ancient prophetess. They shout obscene numbers into their phones: “Tell him five million!” or “How about three hundred?” — presumably leaving out three zeros at the end. “Just get a mortgage!” a woman exclaims, insufferably smooth skin taut over perilous cheekbones. A man marches down New Bond Street, unable to tell the mannequins in the radiant shop fronts — Gucci, Louis Vuitton, Fendi, Prada — from the people outside looking in. His hand is clamped to the phone by his temple. “How’s your event going? Is there food?” he asks while stepping over someone lying on a stained, liquescing cardboard box outside the Loro Piana store.

Sometimes one tires and forgets which party one is attending, and even where one is in one’s own city. At these glittering balls at the end of everything, we’re acidic and intolerable up to our choking gullets. They’re all the same after a while, I realize, leaning on an ornate bronze balustrade, eyeing a sunken dancefloor through a half-empty martini glass, a cynical gallery director to my left. A group of youngish publicists flounce on the balls of shoeless plastered feet to a bossa nova cover of Justin Timberlake’s “Rock Your Body.” They whoop and bump and grind, frolicking mock-flirtatious, Britishly blotto in GANNI mini-dresses and Frankie oversized boyfriend blazers. “This really is peak millennial,” she sighs, transatlantic accented, taking a sneaky deep hit on a pink lemonade-flavored vape. “You’d never catch me dancing on the job like that.”

We’re beyond parody, beyond pardon; perhaps beautiful, almost certainly damned. There’s a deep snobbery about which day you come. The well-gatekept Wednesday is for VIPs. Nobody who’s anybody goes to the public days, apparently. Anybody who’s anybody, and thus someone you probably want to be if you want to be in the art world, shows up on Wednesday and Thursday, and has already wearied and abandoned the sinking ship by Friday. This makes attendance impossible for anyone so frivolous as to have a job or a family requiring their attention. And thus the excitement is over and our skinhead Madonna is leaving, temporarily satiated. She’s in velour travel clothes, décolleté but not too décolleté for the hissing mid-October wind. She exchanges air kisses with a woman with bleach-blonde gelled hair in a very long, black, latex trench coat. “See you in Paris, darling!” she says as she prances into a Eurostar-bound Uber.