By observing expressions of human loneliness materialized in sphinxlike forms, “Frontal Sphinx” offers a constellation of images that reflect on how we, as humans, are haunted by our existence — and, therefore, by our solitude. The show investigates how this complex and everlasting enigma can weigh on diverse artistic productions, from the Neolithic period to twentieth-century painting and contemporary performance, through a nonlinear but penetrating arrow of time.

Addressing various systems of thought structured by humans to support their own existential issues, “Frontal Sphinx” demonstrates how they all inevitably reach a critical point regarding individuality. It is as if all paths lead to a collective existence, and any individual production that forcefully attempts to break through this membrane results in a bewildered expression. The exhibit conducts a reading of different repetitions of the same riddle, but each one rendered via its own individual concepts and visualities.

Organized and curated by Germano Dushá, the show presents fifty-nine works, by more than forty-five artists from around the world, in the ample space of Mendes Wood DM’s gallery in São Paulo. It is a culmination point in Dushá’s crescendoing curatorial practice in recent years, aligned with the Brazilian gallery’s internationalization efforts. With locations in São Paulo, Brussels, and New York, Mendes Wood DM recently announced the opening of a new space at Place des Vosges, in Paris, in July 2023.

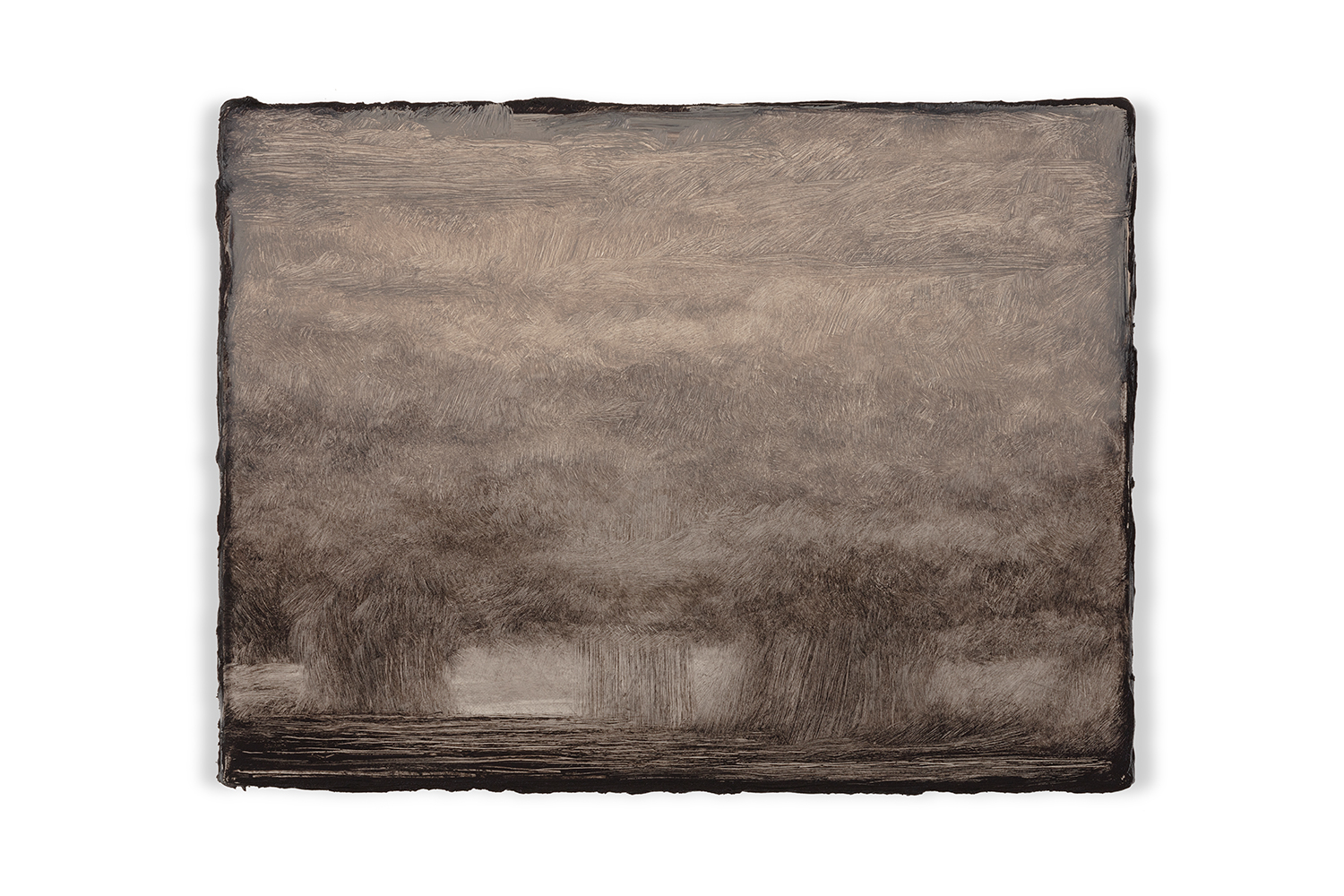

The first space of the show is composed of an altar made with archeological relics from the fourth millennium BC to the sixteenth century AD, and a landscape painting by Lucas Arruda. They form an arc that embraces the viewer as part of a ritual: the archeological pieces, which radiate the power of time, are contrastingly exhibited on industrial steel pedestals, and, instead of a classical figurative or allegorical image in the middle of the shrine, Arruda’s painting hangs on the wall. At the same time that it praises nature as a whole, with its vast landscape, it reaffirms our human smallness, an idea also attested to by the gigantic and enigmatic temporal arcs that emanate from the archaeological pieces.

In the subsequent spaces, the invitation to the gaze — with images and beings that almost say “look at me” or “voilà mon cœur” — is inverted, just as the notion of unilateral influence was shifted by image theorists in recent times. We are not passively influenced by images, but we actively choose to engage what influences us from the platter of offerings served by our social contexts.1 The show proves that the gaze follows the same direction: it is not directed by us, not in our full control anymore — or never was in the beginning — but some things magnetize it without our full consent, applying such a force to it that the eye becomes a passive entity. It is the image that conducts the gaze, not the other way around — as in Sphinx (2020) by Zsófia Keresztes and Paulo Monteiro’s untitled robust lead sculpture (1995).

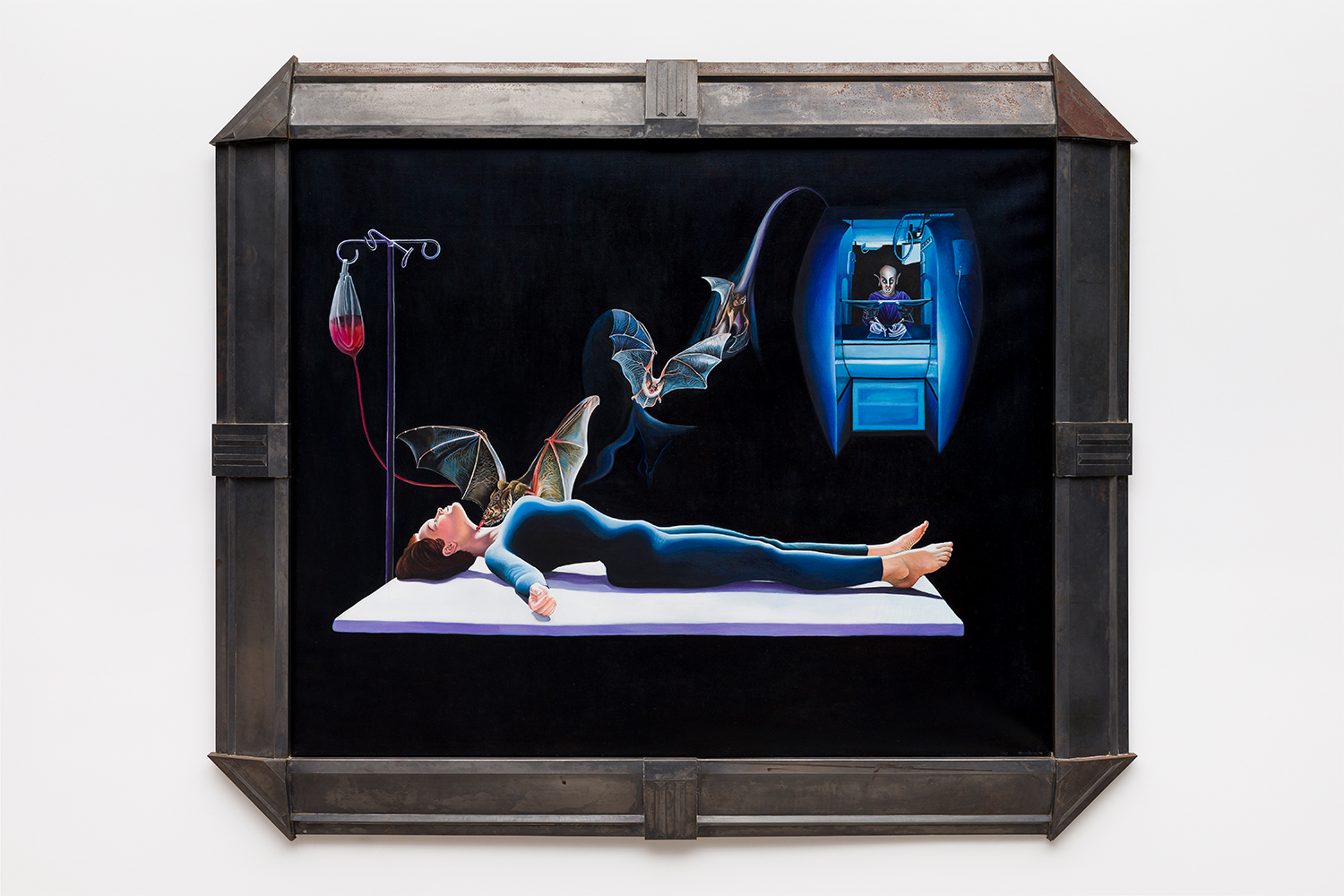

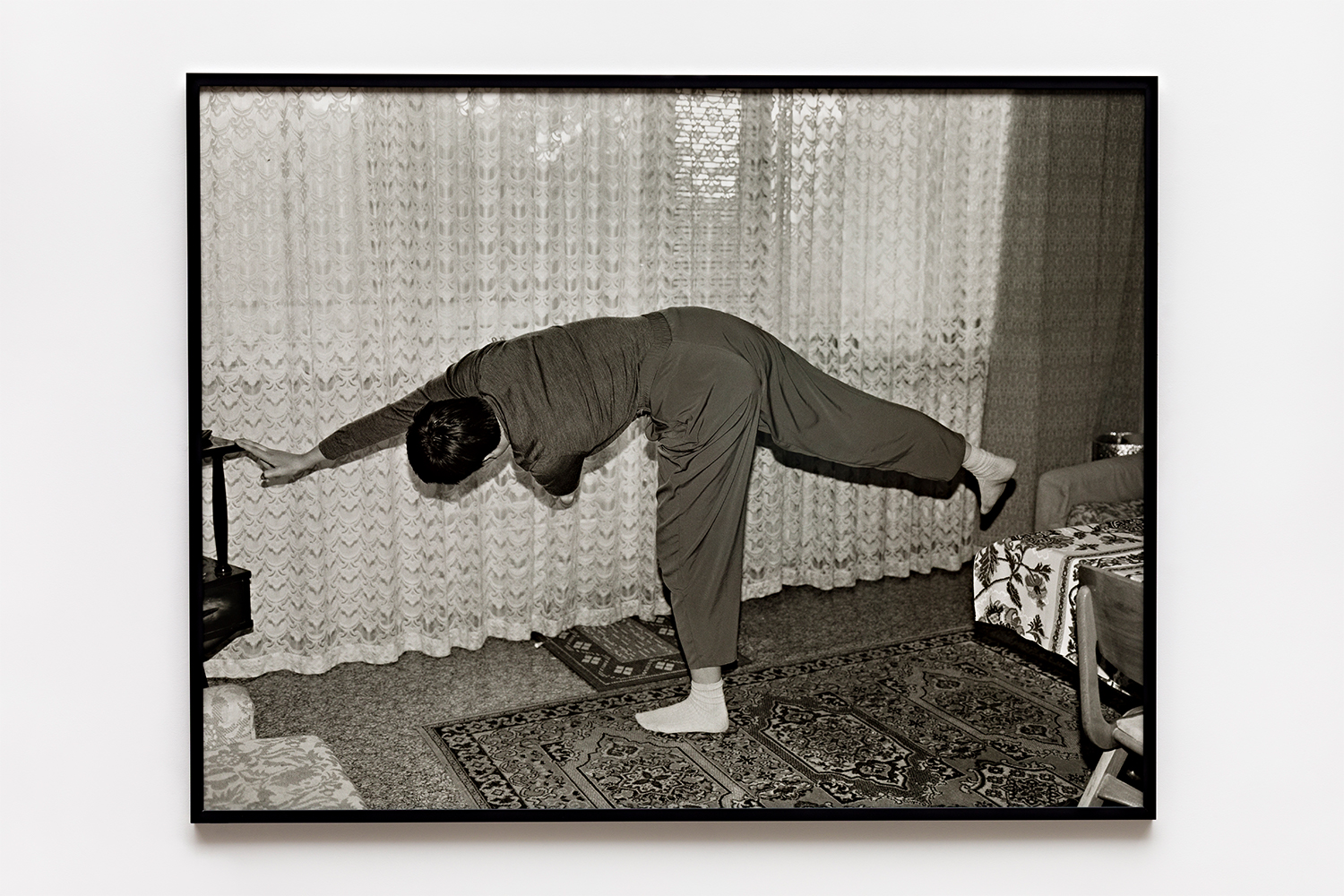

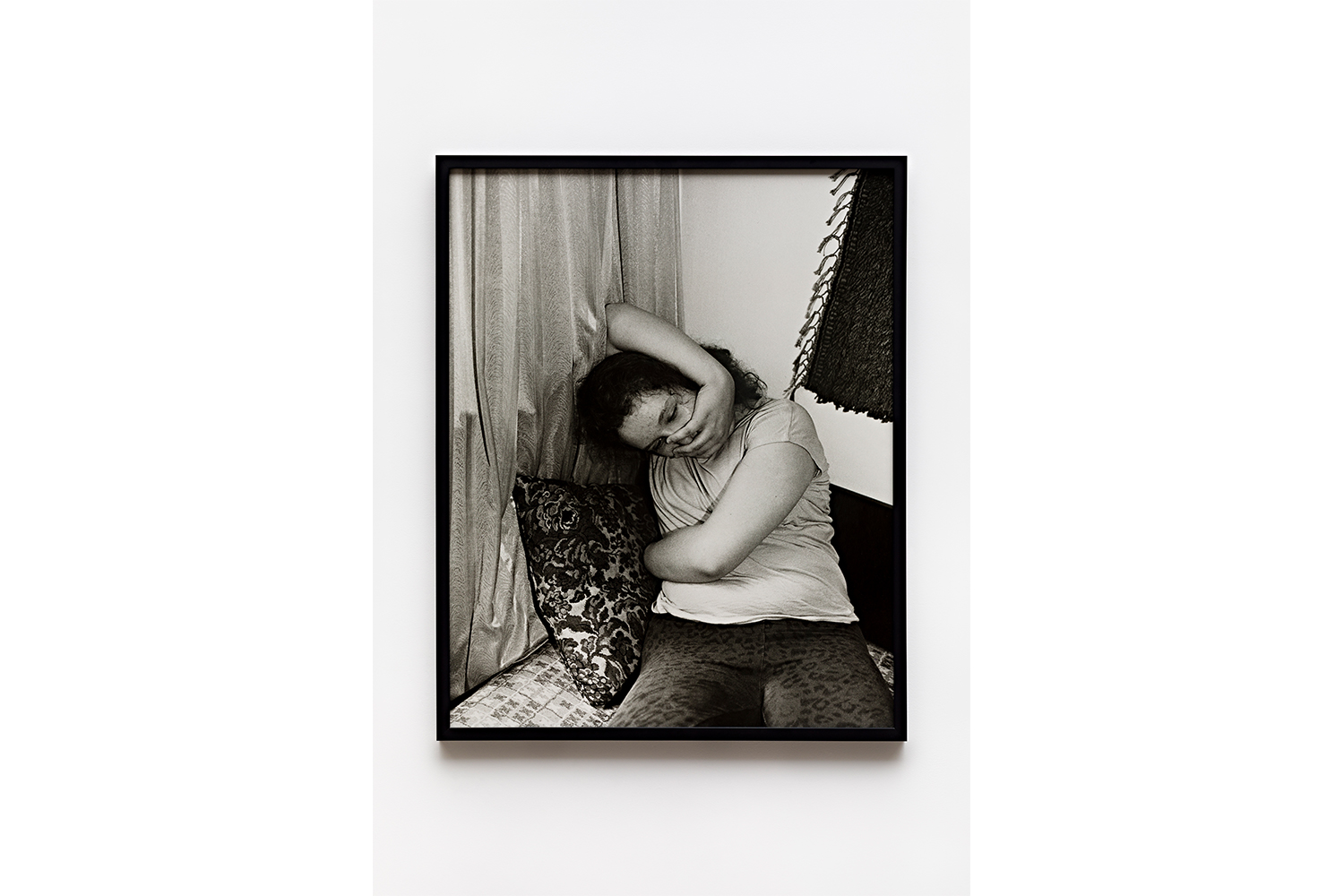

The show highlights that contemporary and Western civilization, throughout the last centuries, is afraid to look at its own nature. And yet it sometimes does it so hyperbolically as to create hyper-realistic figures that point toward representation and not the things themselves,2 as in Anna Uddenberg’s CLIMBER (Pierced Rosebud) (2022). There is also a notable cyborg aesthetic in many of the works in the exhibition, like Franco Palioff’s Show me your nails (2022) and Samuel Guerrero’s Flor (Flower) (2022). In Jonas Van’s Desambiguação (2021), we see gems encrusted in an orthodontic mold that remind us that we are used to the image of crooked teeth being aligned by a machine implanted in our mouths, which exerts traction against the bones for aesthetic purposes — but maybe, if we think it through, we’re not fully comfortable with the idea of it. Free arrangements of human bodies, often aligned with Hellenistic principles of beauty, are read as awkward if in bizarre positions, as in Joanna Piotrowska’s photographs (2015) of seemingly possessed subjects.

Why do we find it strange when parts of other natural species integrate with our own — like bat wings, as in Luiz Roque’s XXI (2021), or in Lynn Randolph’s Transfusions (1995) — but not so much when it comes to human-made things — like the wings of an angel, assuming that religious images are expressed only by humans, or by machines that care for your health and beauty? It not only does not bother us, but we even admire how these devices can provide ethereal moments: Roque’s video also displays a couple dancing to a music box song with one of them in a wheelchair, expressing a sense of affective connection, delicacy, and love. Why is the idea of transplanting a pig’s vein to a human body more repugnant than having your blood fully filtered by a hemodialysis machine? Opening an automaton and exposing its gears can be analogous to lacerating a body and revealing its viscera.

Technologies created by humans — in the material field, such as medicine, physics, or mechanisms of production, but also systems of beliefs and epistemological categorizations — provide us with a sense of control that protects us when facing the unknown and the uncontrollable heat of the universe. Sometimes it is presented as an other, but often it is perceived in ourselves. Our comprehension and production devices are crafted to maintain a sense of human power and control over nature. History itself is also a human technology to tame images, narratives, and events, and the mirrored relations between these entities are collapsing — as illustrated by Paulo Nimer Pjota’s Femme maison (bourgeois) (2023). As Dushá writes in the curatorial text, “the loss of this reference has been painful for humanity; time is how we quantify our attachments.” Humankind is not ready for its own loss of control.

Further along this foggy threshold between culture and nature, one of the exhibition’s questions is whether loneliness is inherent to human existence, as a physiological function of the psyche. Although creating a cohesive argument suggesting that it is visceral given, the show also deliberately presents a mirrored image that attests to the opposite: forms of natural organization that are structured from collectivity — just as some social systems are annihilated by colonialism — and that individualization is a Western cultural malaise. The sphinx itself, as an original cultural and religious entity of African peoples, was usurped by the dynamics of ancient Greek domination — as well as a huge number of African traditions and concepts that were reworked and disseminated by ancient Greece and Rome as their own3 — conquering not only territories but dominating people and narratives in a white, individualist supremacy.

In the presumptuous human way of thinking that dominates contemporary society, contemplating the limits of the human body or the individual often involves reducing nature to the same limited perspective. This approach reflects an individualistic worldview that abstracts humans from natural categories, placing them in a position of dominance over the environment. It creates an illusion of control, as if humans were like entities who can manipulate time, images, and narrative to their will. However, the distorted and gut-wrenching images in “Frontal Sphinx” reveal the loneliness and disconnection that result from a lack of answers, whether inherited or implanted. These shared experiences remind us that we are all connected by this sense of existential uncertainty.