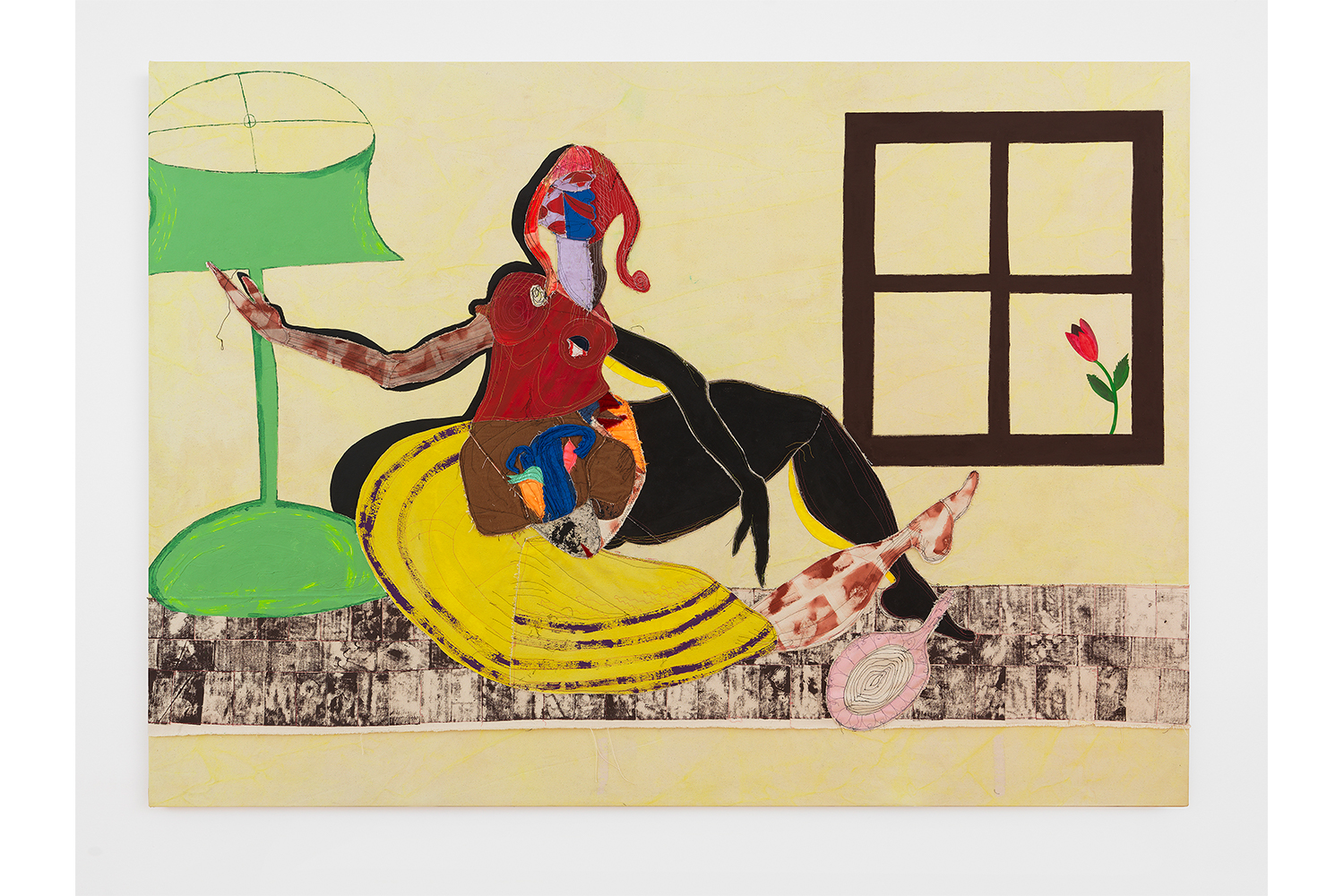

The exhibition “Make Room” opens with a work titled Hysteria (2022) — featuring a cubist-faced figure wearing a striped-and-polka-dotted dress raised above the waist, exposing her vulva. Having the viewer consider a Black female body devoid of shame is the perfect gesture to honor the “make room” title, and American artist Tschabalala Self does just that, carving out space using textile, paint, canvas, and thread. Her first solo exhibition in a European museum — in Dijon, curated by Franck Gautherot and Seungduk Kim (on view through January 22, 2023) — showcases many new works in which the body is flagrantly depicted. On her website, Self criticizes the “voyeuristic tendencies towards the gendered and racialized body; a body which is both exalted and abject.” Her approach to representing it is as politically infused as formally considered: she gives her figures power as a countermeasure to the disempowerment so prevalent in racist societies past and present.

Self explores the complex interiority of Black subjects through portraiture and, more broadly, through collectivity: a universe in which there is only the Black community, where each silhouette is sewn into being. The thread in her paintings has two functions: “a utilitarian purpose of binding all materials together” and, just as powerfully, “dimensionality to define features in the body with the stitch line.” Sewing, she has noted, “allows me to collage onto canvas. Once I removed material hierarchies from my mind, I began to see canvas itself as a textile.” Self’s work, with its hybridity of painting and fabric, evokes a sisterly bond with Faith Ringgold’s patchwork quilts spotlighting the Black American experience. More loosely one might also draw comparisons with Billie Zangewa’s craftsmanship (hand-sewing silk fabrics into collaged portraits that also serve to champion identity and textile) and Art Brut artist Michel Nedjar (who transforms scraps and thread into visceral figures).

Many of Self’s subjects reside in neutral spaces — solid color fields with no horizon line, stripped of environmental cues — where they exist seemingly untouched by the pressures and prejudices that Black bodies are subjected to outside of domestic space. Self’s desire is to “create a cultural vacuum in which these bodies can exist for their own pleasure and self-realization.” She explains that “their role is not to show, explain, or perform but rather ‘to be.’”

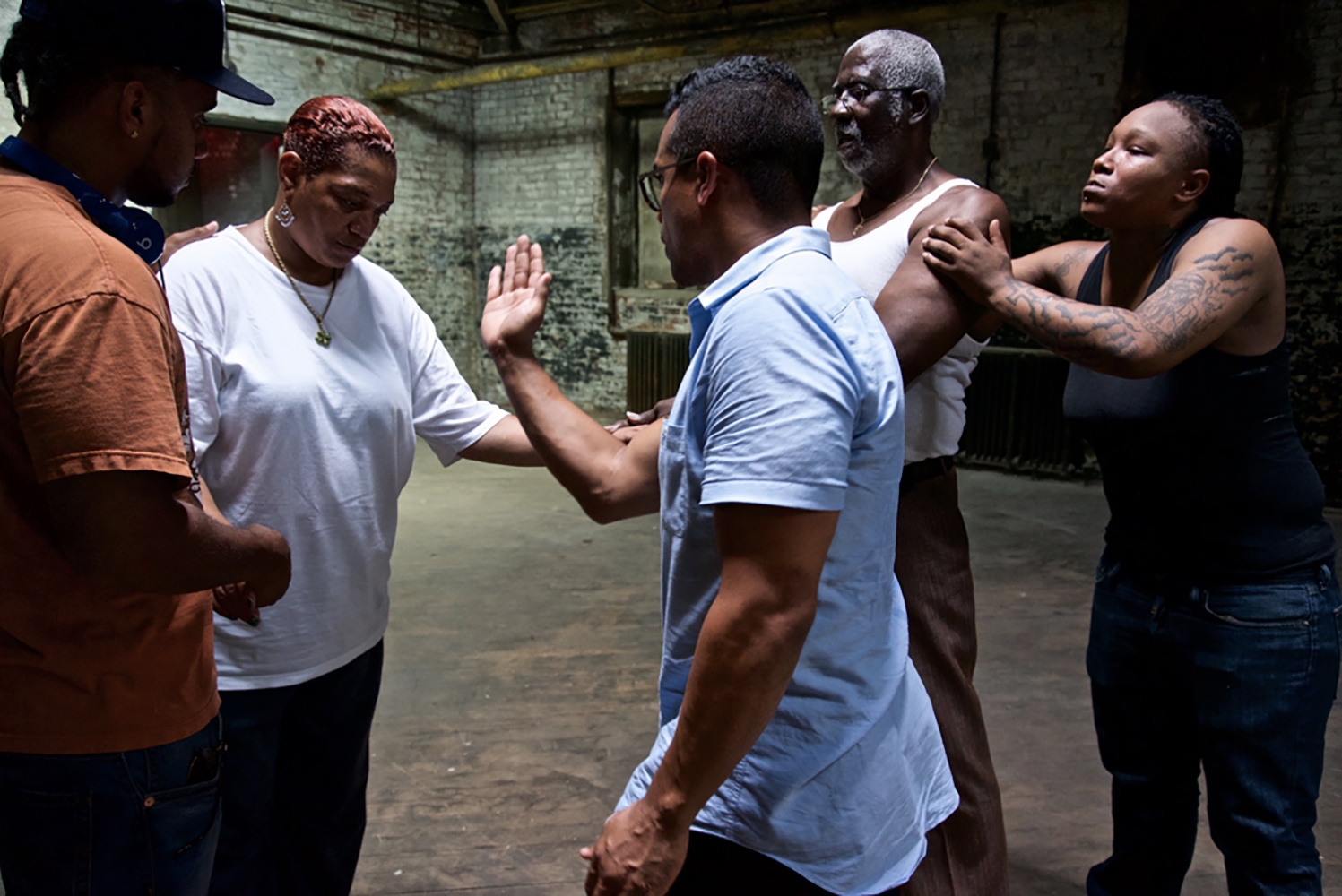

However, there’s a porous sense of object and subject in her new work, alluding to the impossibility of full autonomy. Self has fashioned standalone pieces of furniture on display in the exhibition, which are replicated within recent drawings: her coated-steel Spiral Table (Pink) stands adjacent to Seated Couple in Pink (2022), in which human legs and table legs conflate. The furniture — which also includes lounge chairs — was first introduced during a live performance, Sounding Board, in October 2021 as part of New York’s Performa Biennial at the Jackie Robinson Park Bandshell in Harlem. (A filmed version of the performance is presented at Le Consortium both as a projection within one of the galleries and separately in a theater in the mezzanine.) “I don’t need relaxing — I’d rather stay alert,” one character tellingly says during the performance. That feeling of vigilance may not be completely eradicated from Self’s work.

Porosity between subject and object is also visible beyond the body/furniture meld. There are visual echoes between works: a red checker motif taking up an entire wall recurs in her paintings Loner (2016) and Loner 2 (2022); bits from the dress in Hysteria reappear remixed as a different dress worn by the female figure in the painting Morning (2022). These convergences confirm the ties between the worlds of the canvases even as they feature independent spaces. Overlapping or not, the scenes are willfully commonplace — because while the narrative of Black excellence flourishes elsewhere, Self seems to find relief in banality, the right to simply and comfortably exist.