The feeling is diffuse. One has the impression of entering a space in the middle of an exhibition setup. There are traces of glue on the walls, embroidered fabrics are hung haphazardly, thick sheets are stretched out on the floor. Indeed, one isn’t immediately able to locate the works of artist Myriam Mihindou. What imposes itself at first is a form of appeasement linked to the silence that the pieces summon, due to the fact that the spectator’s gaze must first search for them, inspecting the nooks and crannies of the single room that makes up the exhibition. In “Épiderme,” curated by Guillaume Désanges at La Verrière in Brussels, the concept of surface is at the heart of the show, both literarily and metaphorically: skin, the fabrics that envelop it, and the potential political and aesthetic implications of touch are its main motifs. But, paradoxically, the artist refuses to offer the eye any form of superficiality or obviousness. Throughout the exhibition, no work presented is obviously apprehended; everything escapes the gaze and is negotiated in shades of white, beige, and brown.

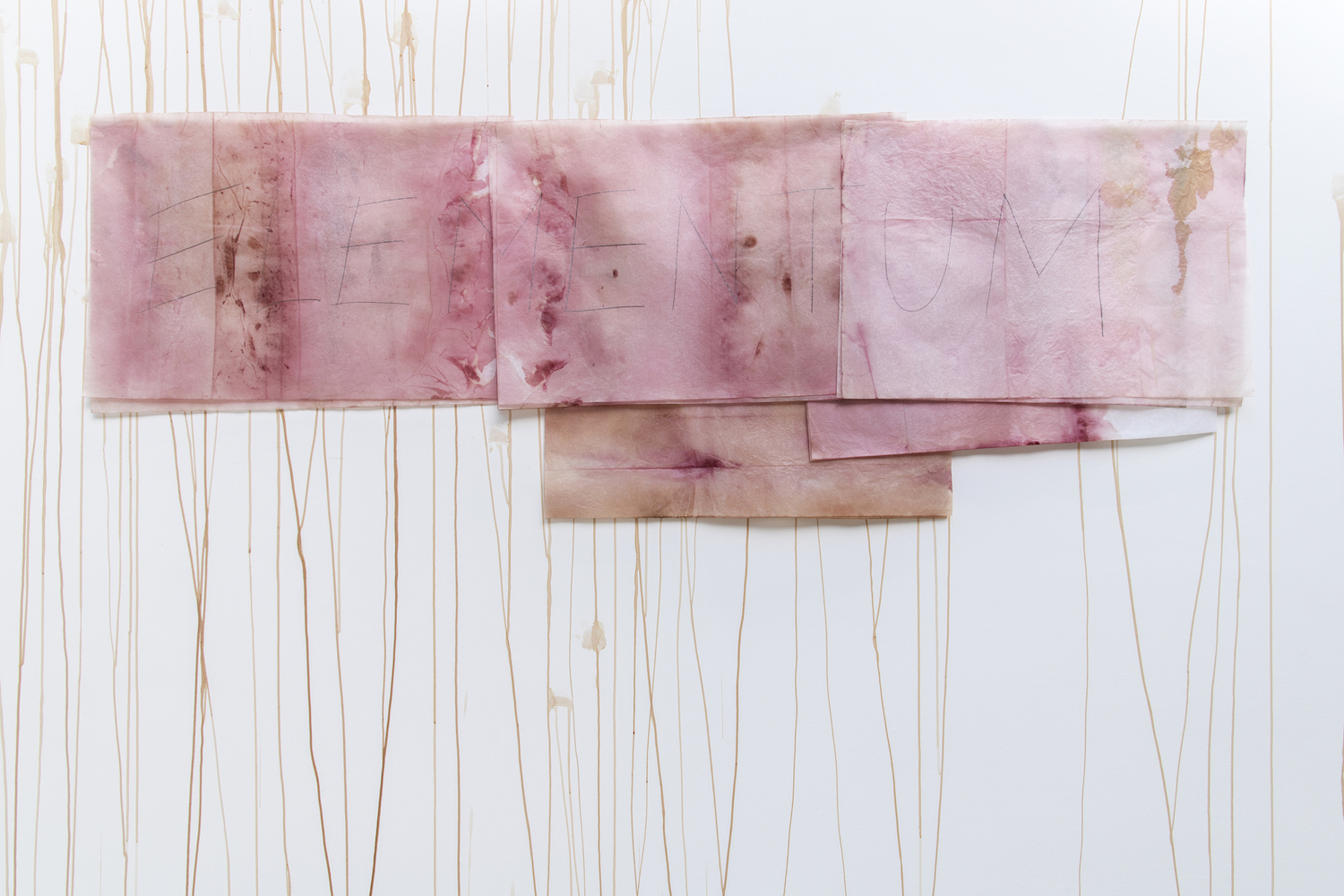

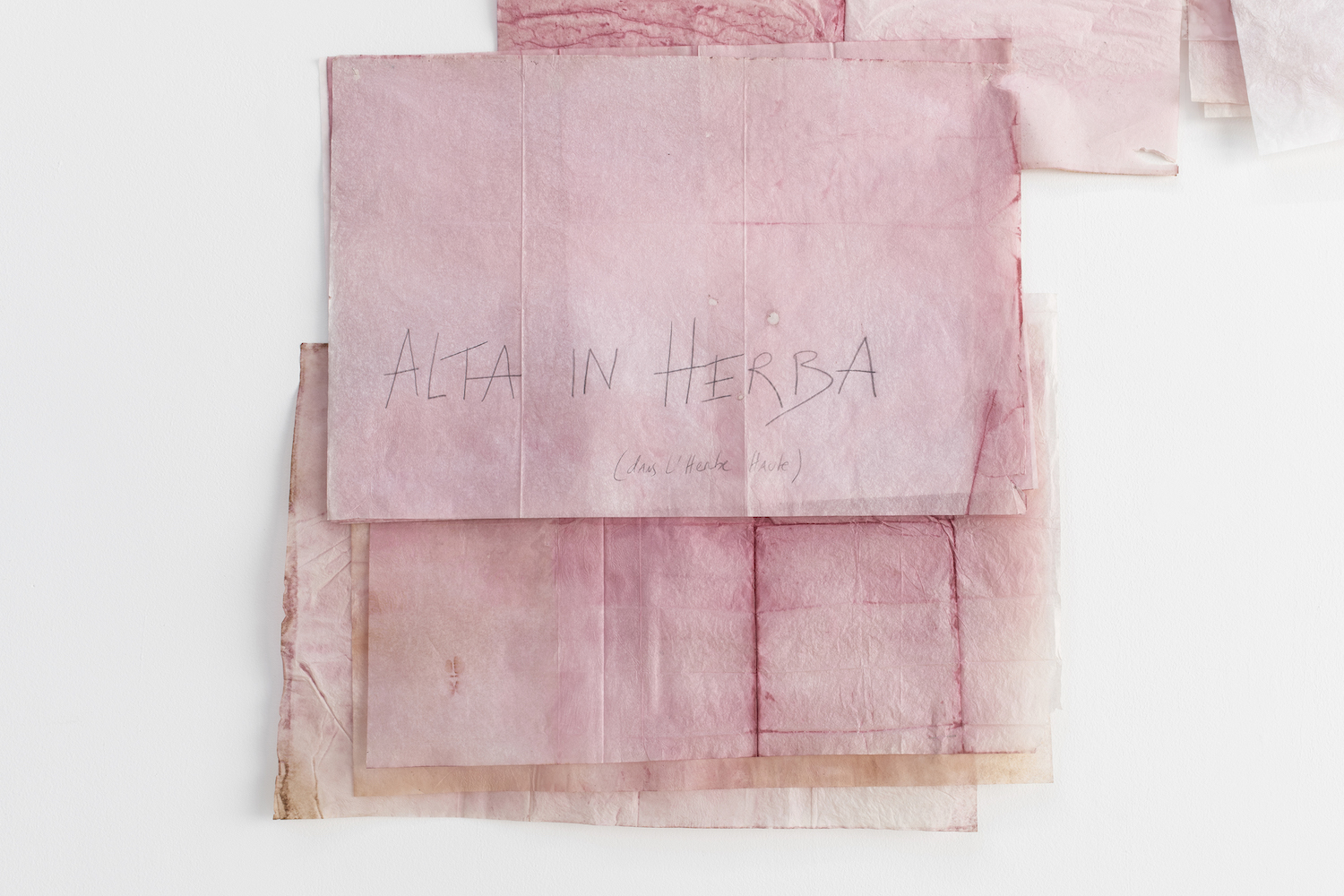

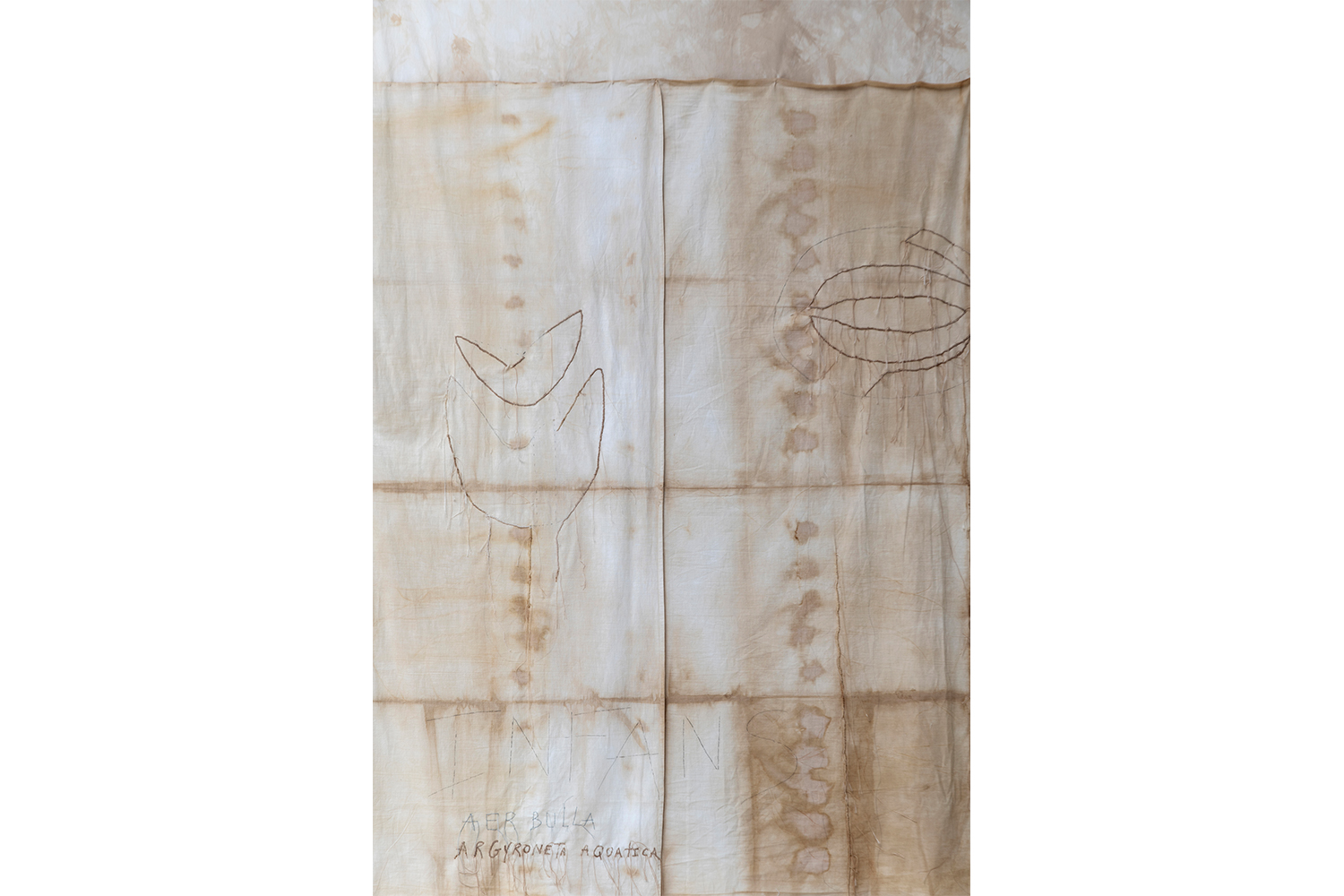

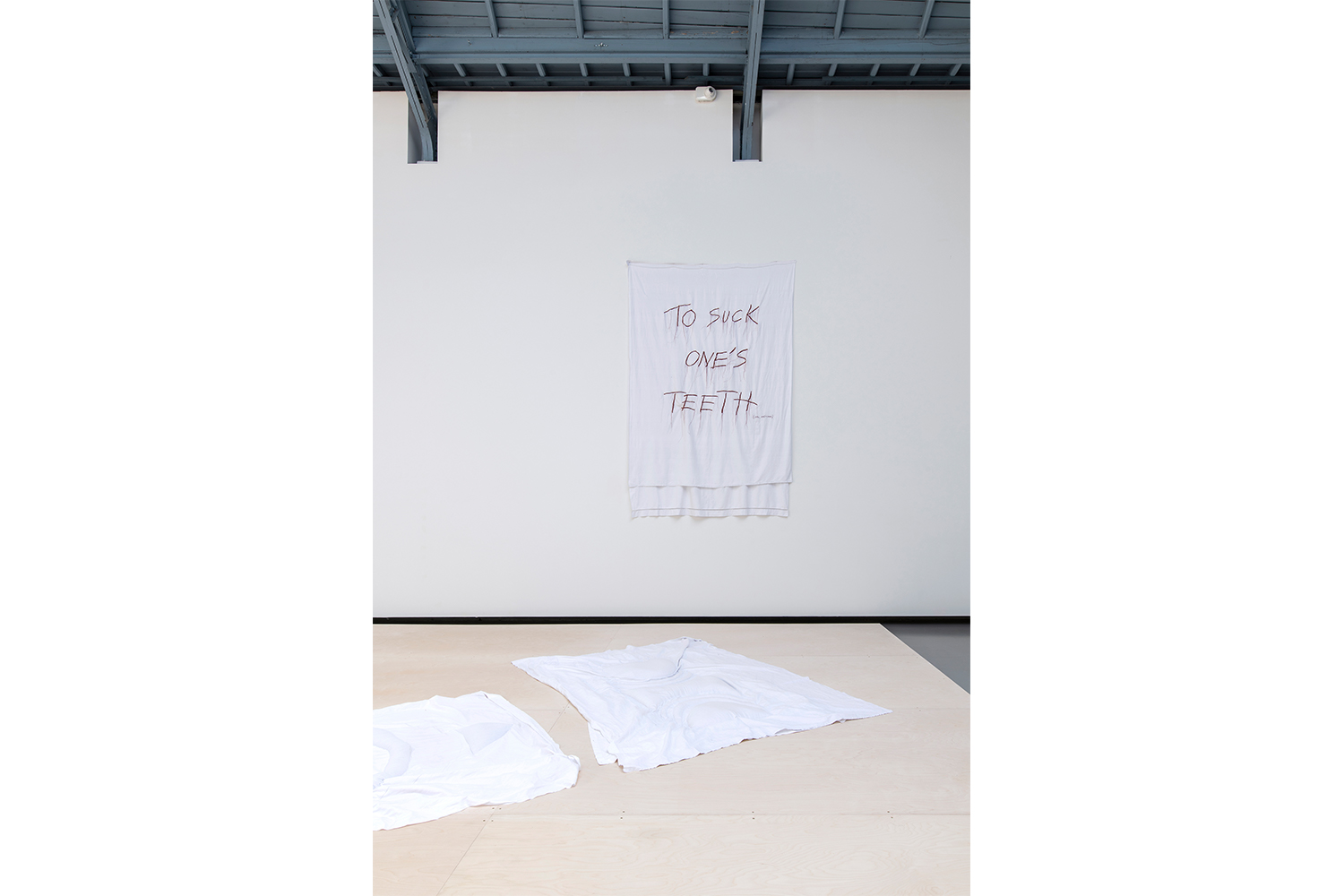

The artist leads the viewer, now acclimated to this feeling of diffuseness, through a dispersed spatial arrangement via a sort of choreography, akin to an investigation carried out by the eye. The spectator must make an effort to understand the craftmanship and material composition of the various works. Some lie on the floor, such as Poussée racine (2022), a large piece of embroidered fabric infused with tea and batik-dyed cotton, wool, polyester thread, and quartz sand. Others hang on the wall, like To suck one’s teeth (2022), a large embroidered sheet on which one can read a slogan. The omnipresence of fabric, whether on the wall or on the floor, is not a coincidence. It is an invitation to lie down in the exhibition as in a bed. Thus, as the visual investigation advances, as we understand that the banners on the walls aim to convey a language of political vindication rooted in fighting against racial inequalities, we understand that the artist seeks to reconcile militancy and softness, care and radicality, in a shamanic rite in which the spectator is the center.

Perhaps we are the missing piece of the diffuse enigma that presented itself at the beginning of the exhibition. In this precise sense, the pieces have been arranged so as to be activated by the visitor. One can lie down in the embroidered sheets, head supported by sand-filled paddles sewn by the artist to fit the shape of the neck. Now lying on the floor of La Verrière, the exhibition forces us to catch our breath. First by disturbing our view, then by gradually forcing the spectator to get closer to the floor and to touch and caress the works. This carnal relationship with the works demystifies the conditions of contemplation often induced by contemporary art exhibitions. Myriam Mihindou allows the spectator to spend a long time in the space, to rest and gain strength by feeling the works while being infused by the political slogans on the walls.

And this is perhaps where the militant force of the exhibition lies. Beyond the sheets hanging on the walls that sometimes resemble protest signs, or the slogans that evoke racial struggles, Myriam Mihindou stages what should be at the heart of art according to her: touch as a new, appeased political communication space. In that respect, “Female” (2000), a series of three Cibachrome photographs representing hands on a red background, pricked with acupuncture needles, sets the scene for the feeling we are left with when we leave the exhibition space. A singular sensation of having touched, of having rubbed up against something both deep and superficial, enigmatic in that the artist’s works nurse us without sparing us.