Yu Nishimura is exhibiting for the second time in Paris. Between Scene of Beholder, his previous exhibition, and the present one, two years striking with their crises have passed by. At the time, he wrote in his diary “The world is fast for me”. Today this is almost an euphemism. His new series of paintings introduce into this mixed feeling of acceleration a moment of astonishing balance.

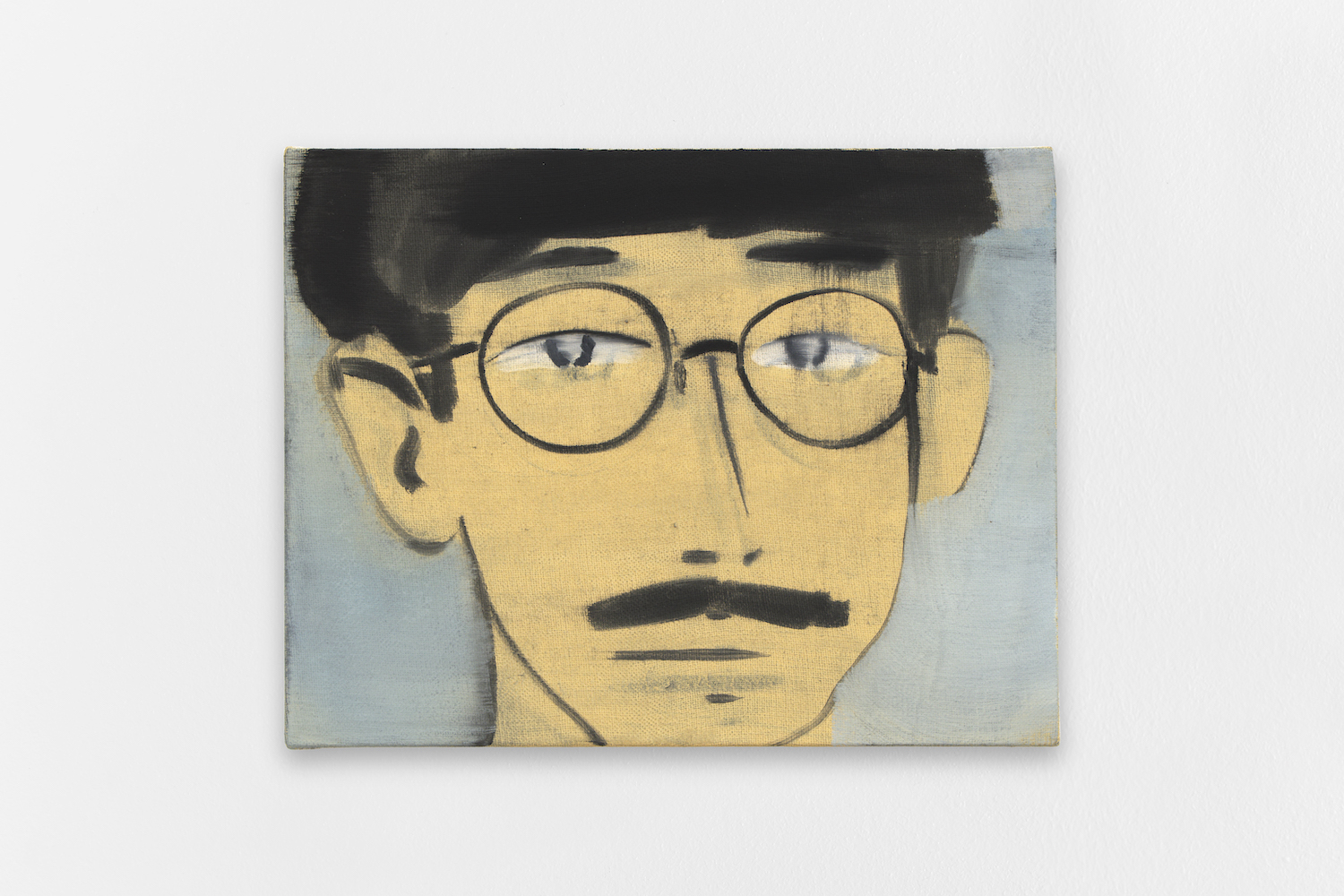

Who are his characters? Sometimes, a portrait looks like the artist himself, sometimes like someone else, and sometimes it is androgynous. Or else a portrait looks like a cat, or else a dog. Often, it is simply traced out, with a black brushstroke, which inevitably brings to mind the black-and-white graphic style of manga.

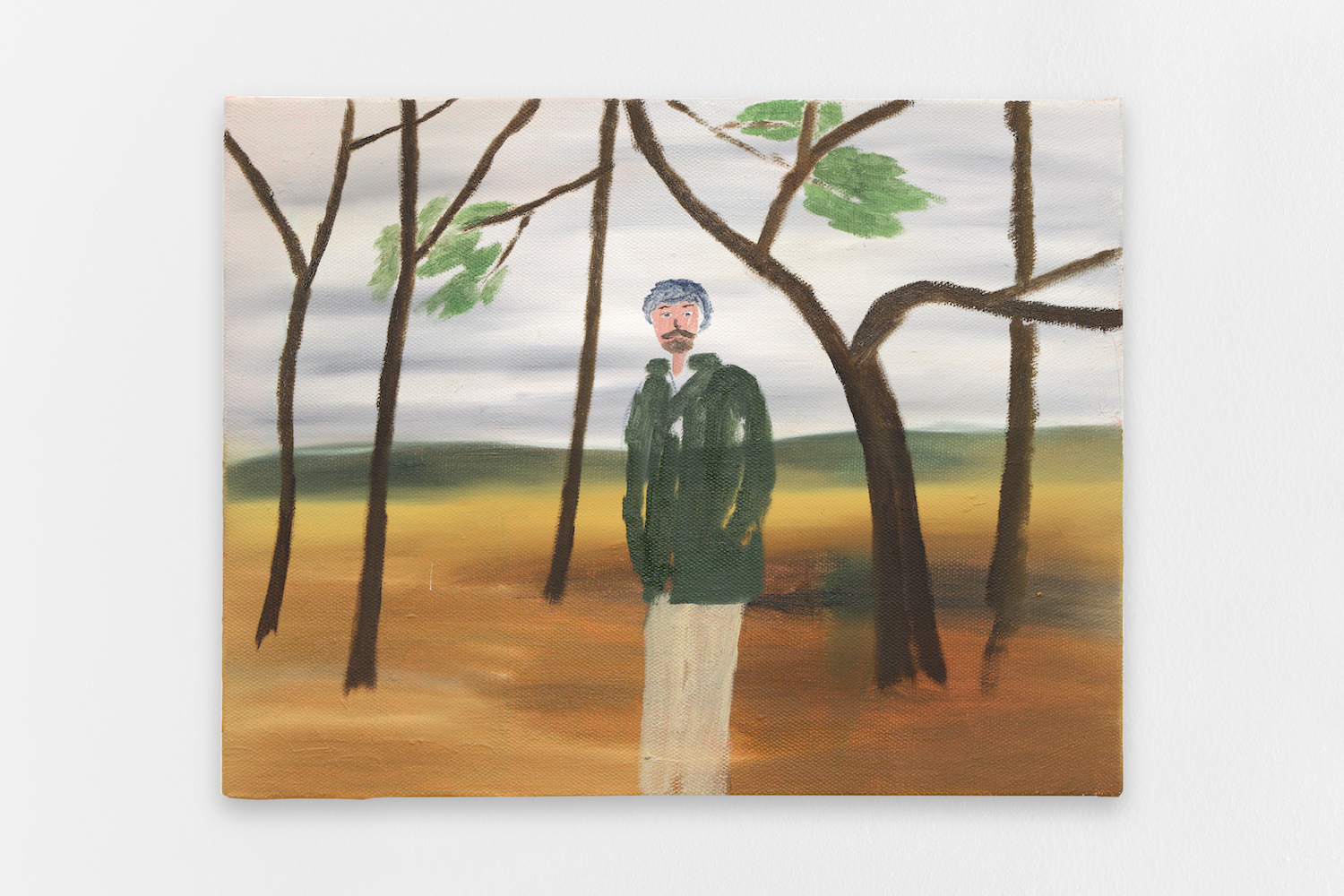

The omnipresent relationship with nature comes from his childhood. But this is not great Nature, but instead natural spaces that subsist/resist in urban spaces. Each of the situations that he paints could be described as follows: small, untamed, uncertain, transitional spaces.

The relationship with filmed images has always had a special vigour in his work. While there are questions raised about the influence of painting on photography or the cinema, the opposite is rarely commented on. For Nishimura, it nevertheless seems relevant to speak of the effects coming from camera shots. Firstly, there is the characteristic blurring, set off by a subtle offsetting of touches. Which places all the elements of a painting on the same level of importance. There are fade-outs. There are zones of over-exposure. There are the appearances of high-angle and of low-angle shots. There are even special effects. As in Bus Stop: a young woman is depicted in two different actions with a time lag of several minutes. She is sitting on a bench is waiting for a friend, alone. She is sitting on a bench is laughing and talking with her friend. Through an effect of simultaneity and doubling, two succeeding moments are merged together, and the time scale of the painting thus becomes loose and stretched. Or, on the contrary, it is ultra-immediate, like a flash. A similar effect is produced in Reflection: a character and its reflection in water are unsynchronised. A motionless, crouched figure. A standing figure, ready to go. Ready to go out of shot, as though to embrace impermanence in an almost off- hand way.

In Open the Window for the first time, Yu Nishimura has separated his canvas in half. A man at his window, two entwined birds. Is this a flashback? In a synchronous desire to isolate a fragment of the scene we are looking at – a zoom? Brian de Palma, who has widely used a split screen, says that it is a meditative form, perfect for counterpoints, but inappropriate for running together shots extremely quickly. There is still here the question of how time is treated, with a confident fragility. Sure enough, Time is a fusion between several historical ways of measuring time: mechanical, analog and digital. When it comes to time and space, Yu Nishimura lets us reconstruct our own notions. With no apparent political manifesto, his paintings pin down moments that never seem fixed, and which flirt with the undiscernible.