The opening weekend of the Lofoten International Art Festival ended not exactly with an éclat, but with a remark that was controversial, at least as panels on biennials go. A previous curator of the show stated toward the end of the final discussion that she liked failure, and that she considers it a way to break free from capitalist constraints. One half of the curatorial duo Francesco Urbano Ragazzi, who are responsible for this year’s edition of LIAF, differed: “I like success,” he said. In fact, he prefers miracles to failures. More than a witty comeback, this rings true. Perhaps the rebranding of failure — personal, artistic, entrepreneurial — into success is the greatest feat of contemporary capitalism.

This edition of the festival, held just off Norway’s northwestern coast, draws less on failure and more on serendipitous encounters. The curators engage in a form of myth-making. A few days earlier, the curatorial team generated intellectual excitement with their opening statement, which they gave in a low-ceilinged, dimly lit room in the Lofoten Kulturhus, where they turned history and geology into plot lines, longue durée-style.

On the archipelago, where hardly a detail escapes the viewer, the works keep only a tenuous link to the landscape, if at all. Most avoid the monumental, except maybe for Haroon Mirza’s light-activated installations Message from a Star (Solar Symphony 12) and Light Work xliv (both 2022). But at no point does the show, with its thirty-seven artists, feel overly sensational. Svolvaer, population 4720, serves as the center of the biennial, while most of the venues are in Kabelvåg, a neighboring town. The curators opted to use materials at hand: poor materials if need be, faulty materials if there was nothing else. They refrained from building temporary structures. Instead, they used extant spaces that tend to give the exhibition a makeshift appearance. “The exhibited works,” write the curators, “establish a direct dialogue with the architecture that houses them,” which means nothing has been built for this, and the artworks — mostly commissioned — react to what’s already in place: the backrooms of a disused data center; the rehearsal stage of a film school; the courtroom where German artist Kurt Schwitters was condemned to a labor camp by Nazi authorities; an old primary school that will probably be torn down soon; and a local museum that is dedicated to the brooding work of the painter Kaare Espolin Johnson, temporarily renamed the Museum of the Sun.

This institution now also houses the work of Gaia Fugazza, among others, who made small-scale ceramics, flat and fashioned out of impossibly fine clay. In preparation for these sometimes-zoomorphic pieces, Fugazza read Norse and Christian creation myths, and the series is called “Hranrād” (2022), which translates as “whale-road.”

Fugazza’s work shares a space with Rimaldas Vikšraitis, whose series “At the Edge of the Known World” assembles photographs taken between 1978 and 2008 in the countryside where the Lithuanian artist grew up. He idealizes little about his subjects, who engage in drunk revelry, look sad and happy, and, above all, display a raw joy within decidedly non-idyllic settings.

More intricate pieces avoid the monumental, as if to escape the clichés of the surrounding landscape, which has been inscribed with meaning: sublime gothic imaginary, fishermen’s tales that date back to the Middle Ages, and more recent narratives about the fragility of ecosystems.

The monumental is reserved for an older endeavor, the Artscape Nordland, inaugurated in 1992 — perhaps the first time the international contemporary art world made landfall in Lofoten. One anecdote has it that the sculptor Dan Graham was driven along the coast while asleep in the back of a car until, awakening at one specific bay, he determined it would be the spot for his large, concave mirror, which stands there like a mirage. The preparatory documents for this project, as well as other sculptures of the public exhibition, are now exhibited at LIAF. Artscape Nordland, in the early 1990s, marked the beginning of a time in which contemporary art claimed a socially relevant role, and exhibitions became sites of coded dissent, a mode that is still in operation at most biennials today.

Leading up to the main show, Francesco Urbano Ragazzi have mounted other exhibitions. One was Kenneth Goldsmith’s show “Retyping a Library” (2022) in Kunstnerhus in Oslo, for which the US artist did just that. He typed up his personal library and arranged the manuscripts in boxes so as to recall minimalist sculpture. Like much of Goldsmith’s work, the project tackles authorship and originality. The curators say that sometimes — and certainly in this case — the copy is better than the original. But a bigger question remains: Which canon is reproduced here? And is the claim that all culture is a copy of a copy, ad infinitum, still noteworthy?

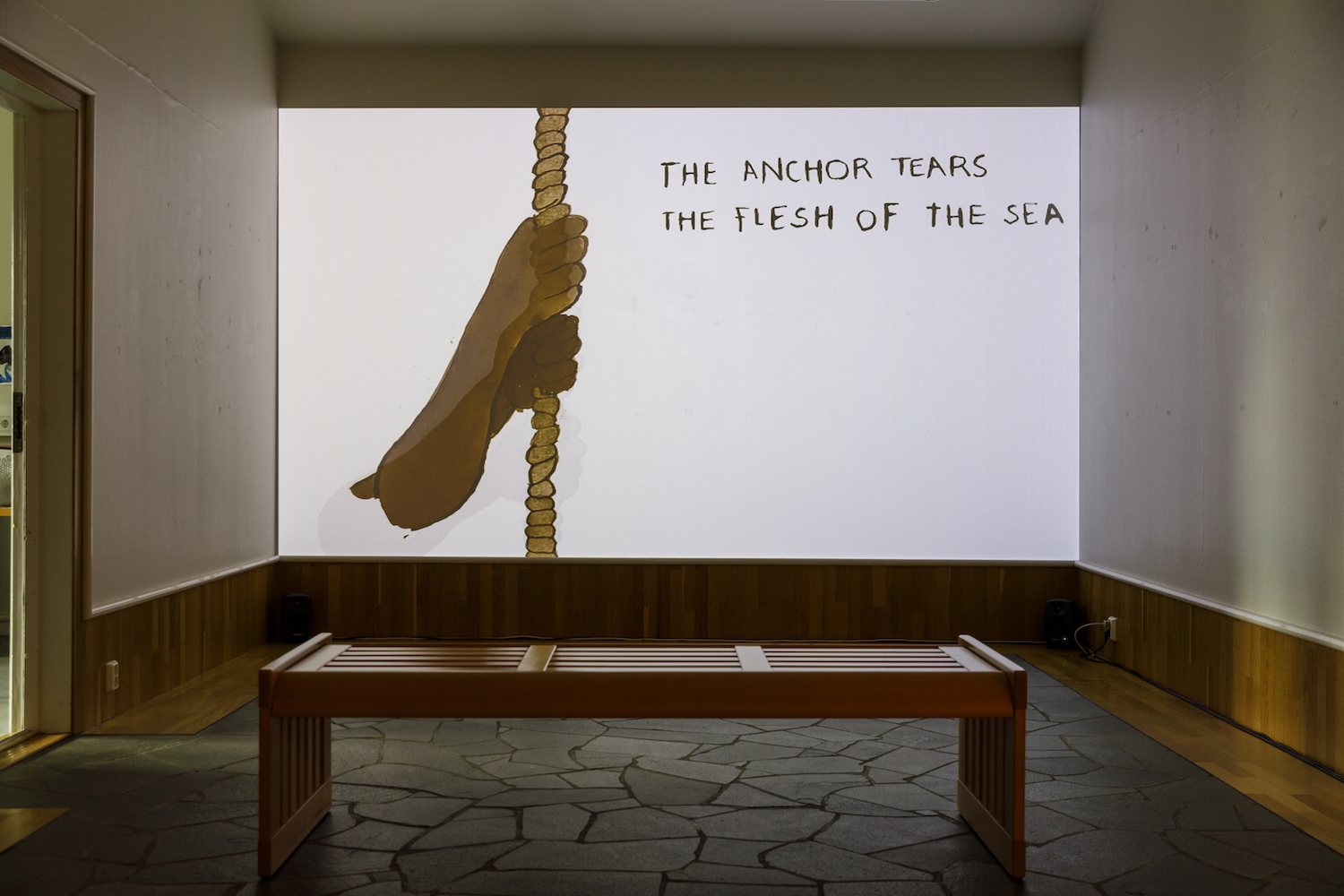

Another of these prologues took place in the parlor of a women’s prison in Venice, the Casa di Reclusione Femminile della Giudecca. The work, devised by Pauline Curnier Jardin in collaboration with the inmates, is continued in Kabelvåg as a film installation with drawings based on a collectively written script. There is a great appeal to making something for a small number of people, especially at a time when the dissemination of content, incentivized by digital platforms and, by extension, the art world, often leads only to obfuscation and aesthetic flattening. The audience for an installation in a women’s prison, on the other hand, is as exclusive as it gets, although a limited number of visitors were admitted during the Venice Biennale. Again and again LIAF plays on variations of seclusion and remoteness.

Seclusion is also what comes to mind when looking at Group Crit (2022). The seventy-minute video work by Sille Storihle features students at the film and art school, which is now affiliated with the university in Tromsø, a city even further north. The students role-play the group critique customary in art school: they confront each other, which makes for uncomfortable comedy.

Above all, it recalls the original site of creativity to which this biennial refers. The title of LIAF 2022, “Fantasmagoriana,” is taken from a French anthology of ghost stories published in 1812. It was read by Mary and Percy Shelley, Claire Clairmont, John Polidori, and Lord Byron while they were in lockdown in a villa by the banks of Lake Geneva during the aftermath of the Year Without a Summer, the consequence of a volcanic eruption in Indonesia in 1815. While in Switzerland, the group of young poets became an incubator for what would become gothic fiction, and Mary Shelley’s novel Frankenstein uses the Arctic as the backdrop for her sinister version of the sublime. The catalogue for LIAF includes a flowchart that centers on this group of writers, connecting cultural, political, and economic developments in a dazzling maze of arrows.

While the proclamations of the biennial speak about conditions of extreme isolation, in fact, these islands are well lit at night, and it’s not difficult to get around. All of this, however, eschews easy entertainment value; although the Lofoten are a popular destination for travelers, the biennial is not really a tourist draw. An uneasy question hovers over the show: Who is this really for?

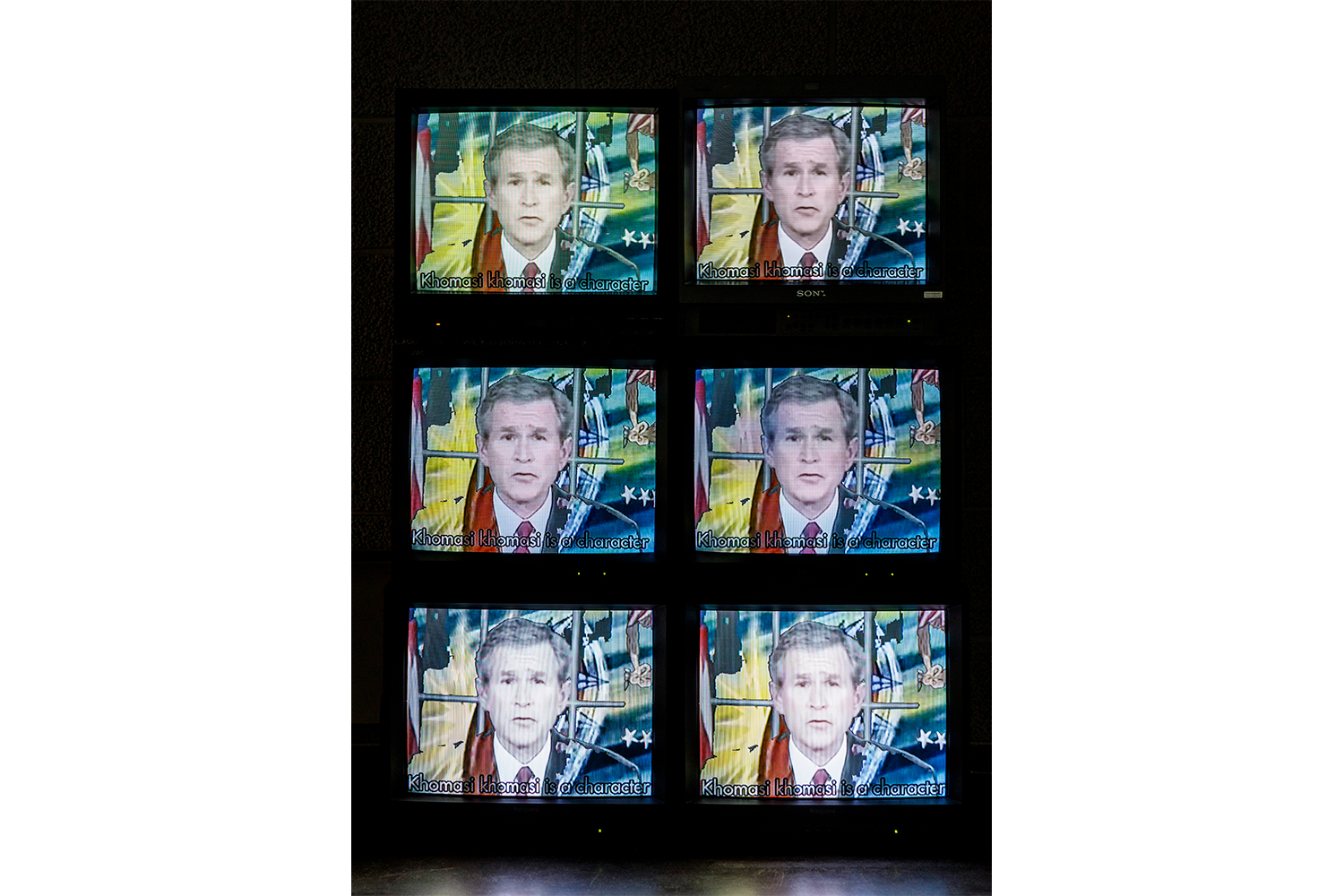

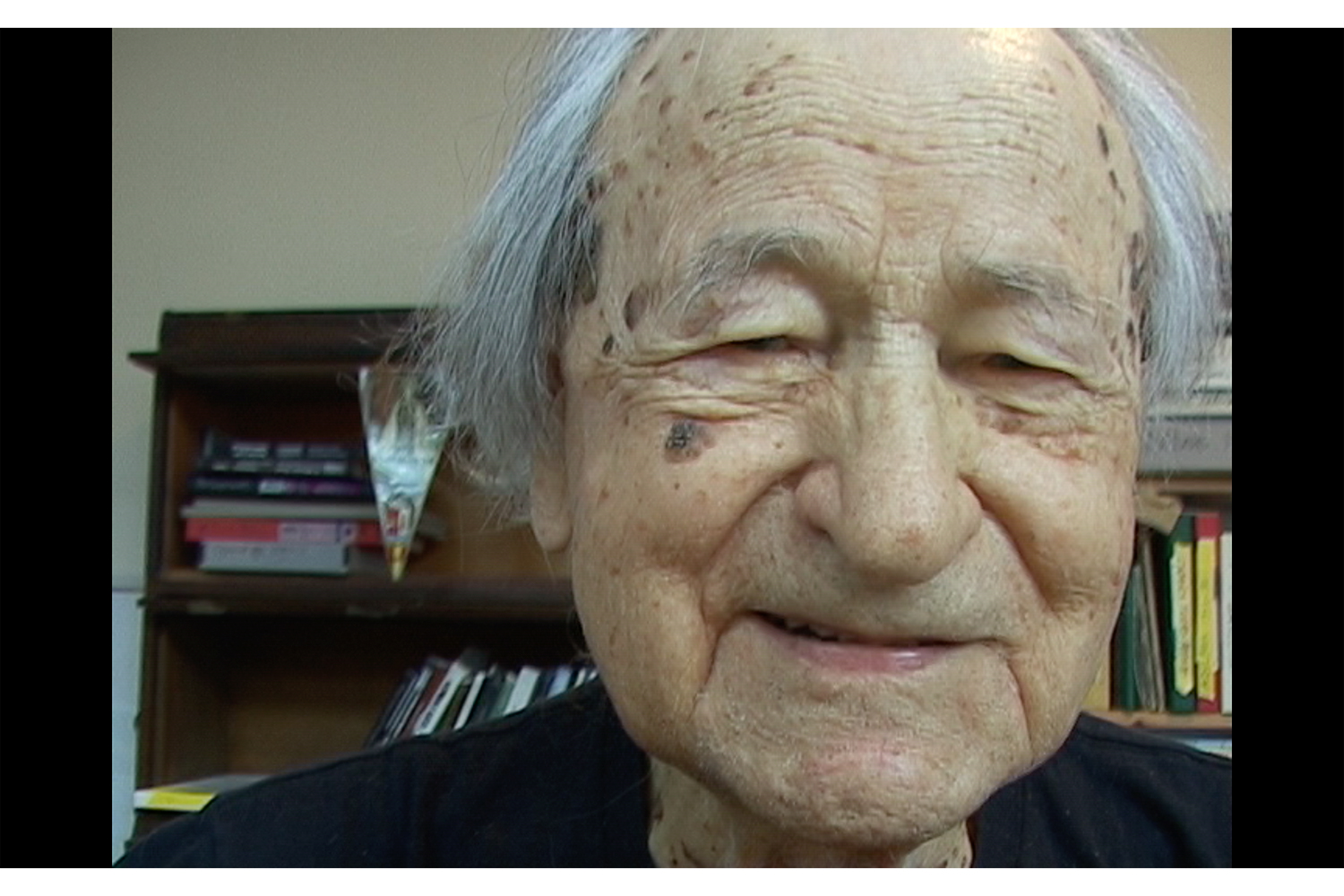

As a manifesto, Francesco Urbano Ragazzi included an excerpt from Jonas Mekas’s video diary, Orquestina de Pigmeos (2017), which the late filmmaker recorded after traveling Europe and its biennials. He complained about the sheer size of blockbuster exhibitions — their bigness, to borrow a term from Rem Koolhaas — and how he missed something important. On his trip back, in Madrid, he chanced upon the rehearsal of a group of Romanian singers, who sing a melodic crescendo while they smoke. “This is what art is all about for me,” says Mekas shakily, “the personal.” Sometimes it feels like Francesco Urbano Ragazzi set out to retroactively fulfill Mekas’s vision of the small and whimsical.