“There’s a lot of reciprocity between my lived life and my painting life,” Danielle Orchard notes, surveying her canvases at Galerie Perrotin in Paris, where she is inaugurating her solo show “Page Turner.” The Brooklyn-based artist compellingly explores female corporeality and nudity in a planar style; the depicted scenes have a sober feel, despite her boldly saturated color palette. Her work is replete with art-historical winks to existing tableaux: “Often I’ll start with a gesture that I’m interested in from another painter, or something in real life that reminds me of a painting.” The references can be subtle or overt — to such artists as Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Henri Matisse, Georges de La Tour, and Balthus — but always reinvented.

For the latter painterly reference, Orchard revamped the 1938 painting Thérèse Dreaming into Lessons (2022). “I became interested in what could have happened to that character, that subject, in adulthood. The cat in the original painting is highly sexualized: it’s lapping milk, and it’s a very obvious erotic image. I thought it would be funny to have her grow up into a cat lady.” The reclining nude is surrounded by slinky felines; they circulate in the midst of an elegant vase of pink lilies, which — a former roommate of Orchard’s found out the hard way — is fatally toxic to such pets, and the artist describes the flowers as “a quiet threat.” Countering the tacit danger is the playfulness of “cat butts, repeated like cartoon star-shaped motifs,” which parallel the shape of the pet owner’s belly button. This is Orchard’s formal signature: creating visual continuums.

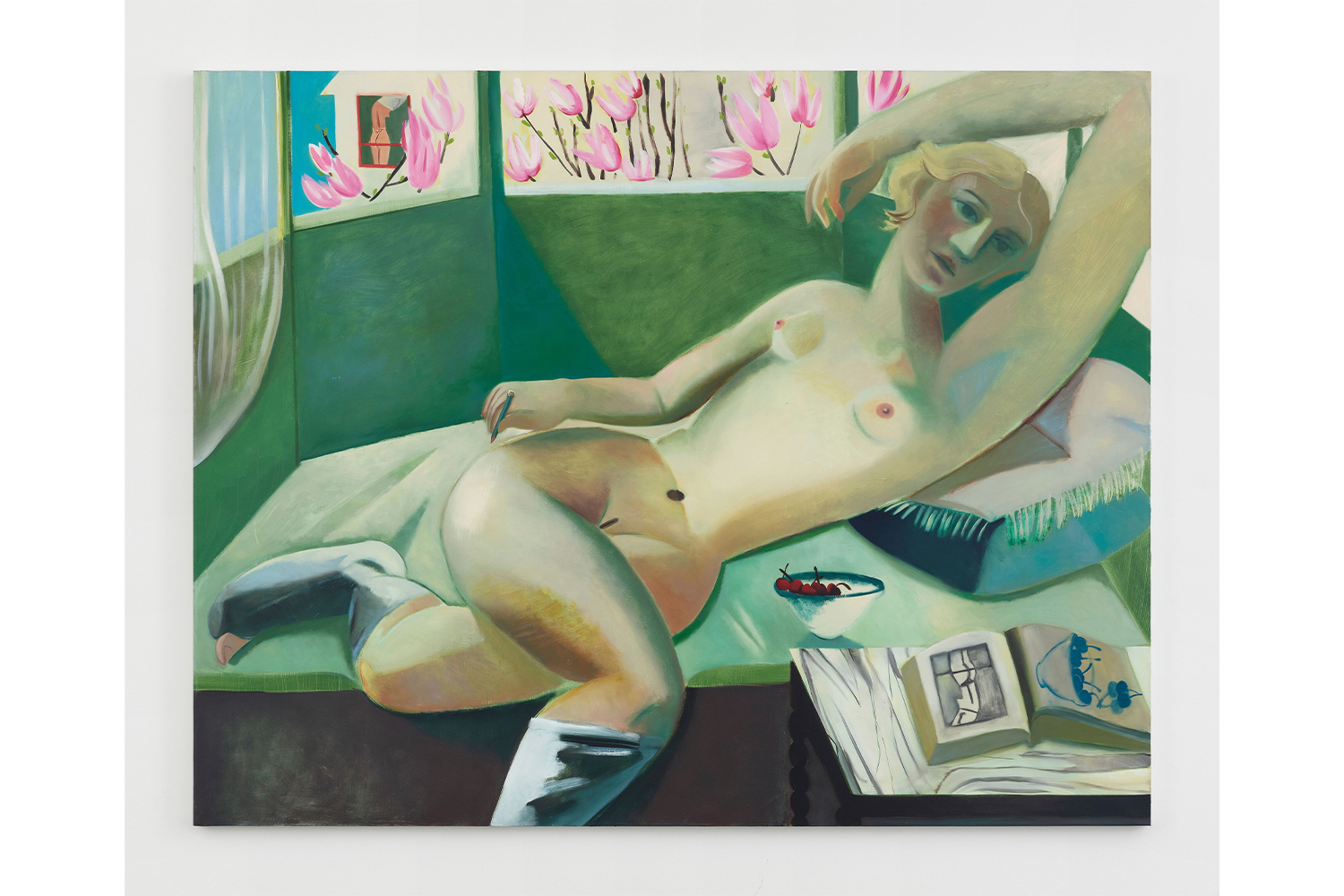

The technique of visual continuity is also evident in Rear Window (2022), featuring a reclining woman in a setting peppered with eerie doublings and compositional echoes: a second nude is voyeuristically visible through a small window behind the frontal subject; a bowl of red cherries on a table twins a sketch of the same fruit on a splayed-open page. “It’s a visual game… it conveys a lot of the metaphysical dimensions of painting. What is real to the people inhabiting these spaces? Their world is referring to ours, but it has its own kind of internal logic as well,” Orchard notes.

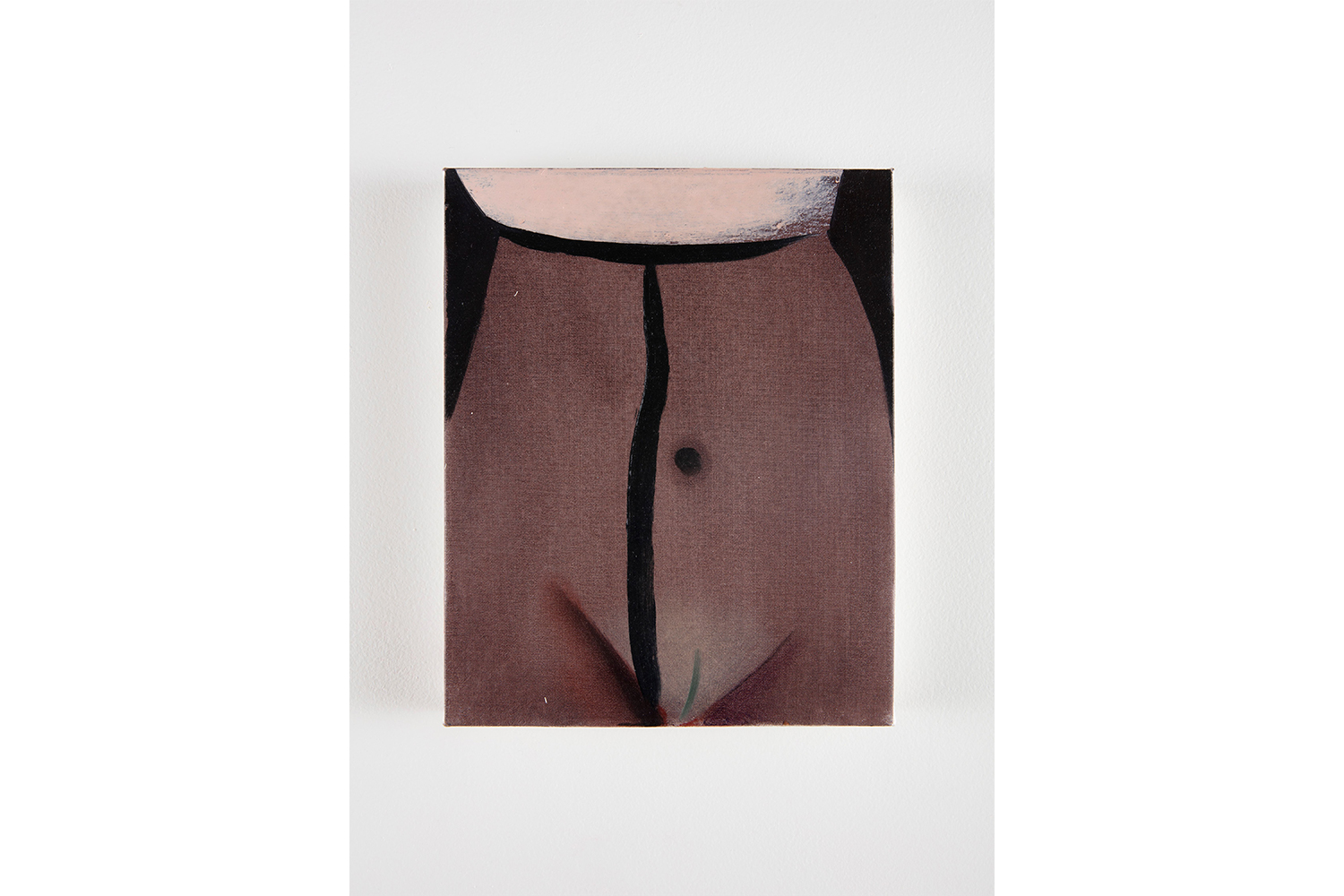

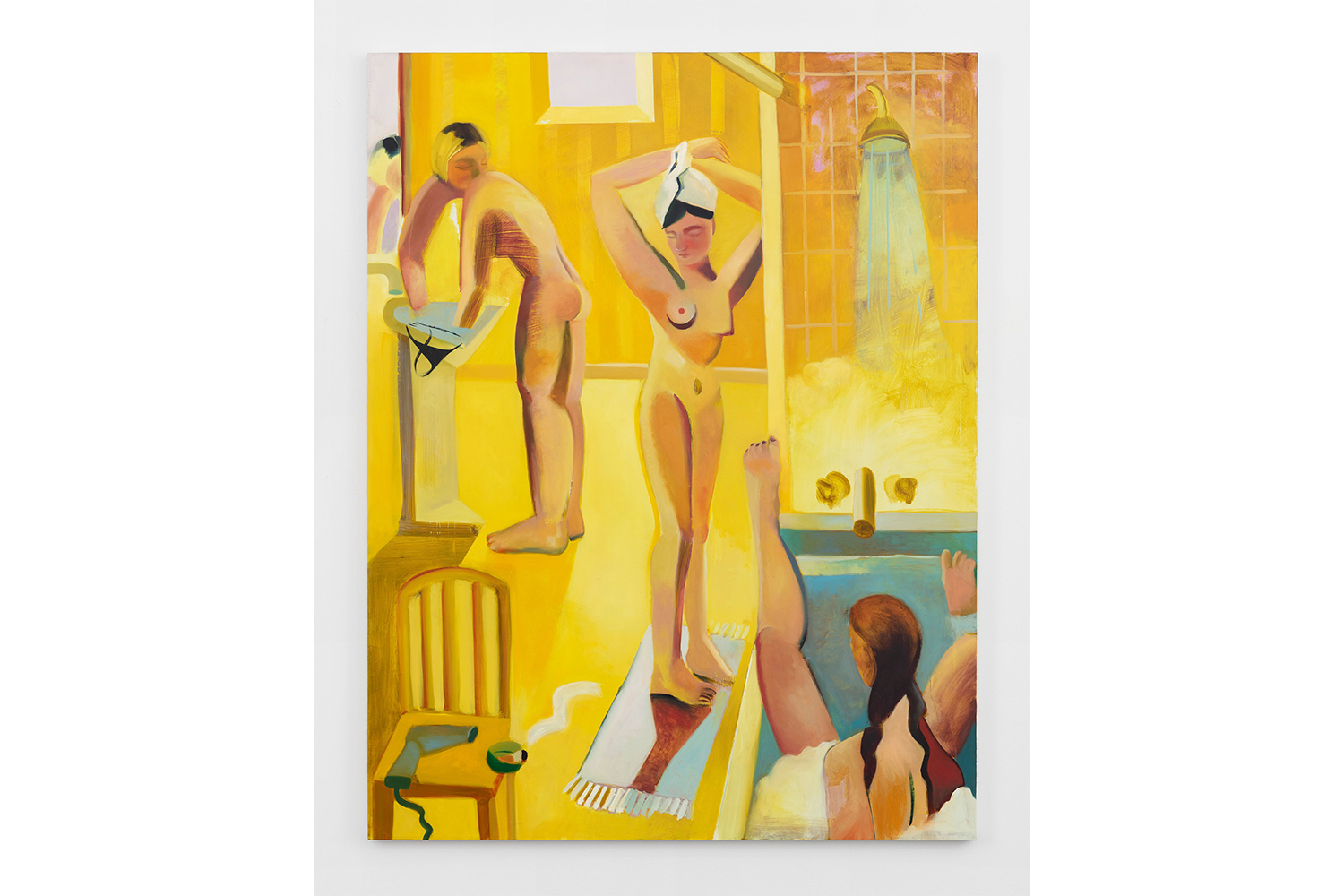

Each of her always-female subjects incarnates a form of modern odalisque, the body articulating “this accident of anatomy” with purposefully extended lower vertebra. “We’re so used to the female body being manipulated and cajoled, which is something that I’m participating in fully and readily… but I like to sort of poke fun at it.” Indeed, Orchard’s paintings expressly confront the lived female experience with a trademark mix of humor and malaise, spotlighting “common moments of failure experienced as a woman, particularly around the body.” Lint (2022), for example, is carefully cropped to showcase just a low waist and genitalia, hemmed in by sheer pantyhose. Drawing from her own girlhood, Orchard recalls: “Pantyhose just never worked for me. It’s such a visceral experience wearing those things. But then it also has this erotic, sexualized component… The two experiences are disjointed: the wearing, and the viewing.” She adds: “The effect that pantyhose have on the body feels sculptural, related to artmaking… like forming your body into an acceptable shape for going out.”

The strains of contemporary female toilette are similarly depicted in Shaving (2022), featuring ankles and feet against a blue-tiled shower — a visual citation to the opening scene of Psycho. “You don’t see the wounds inflicted, you just see the blood spiraling, and it’s more menacing. I’m interested in that idea of something outside the frame being the ultimate subject,” Orchard says of replicating this portentous cinematic trope. The assumption is that the red leak is menstrual blood, but for Orchard, it more largely reflects the various ways women deal with the fragility of their own bodies, repackaging them for display in daily life.