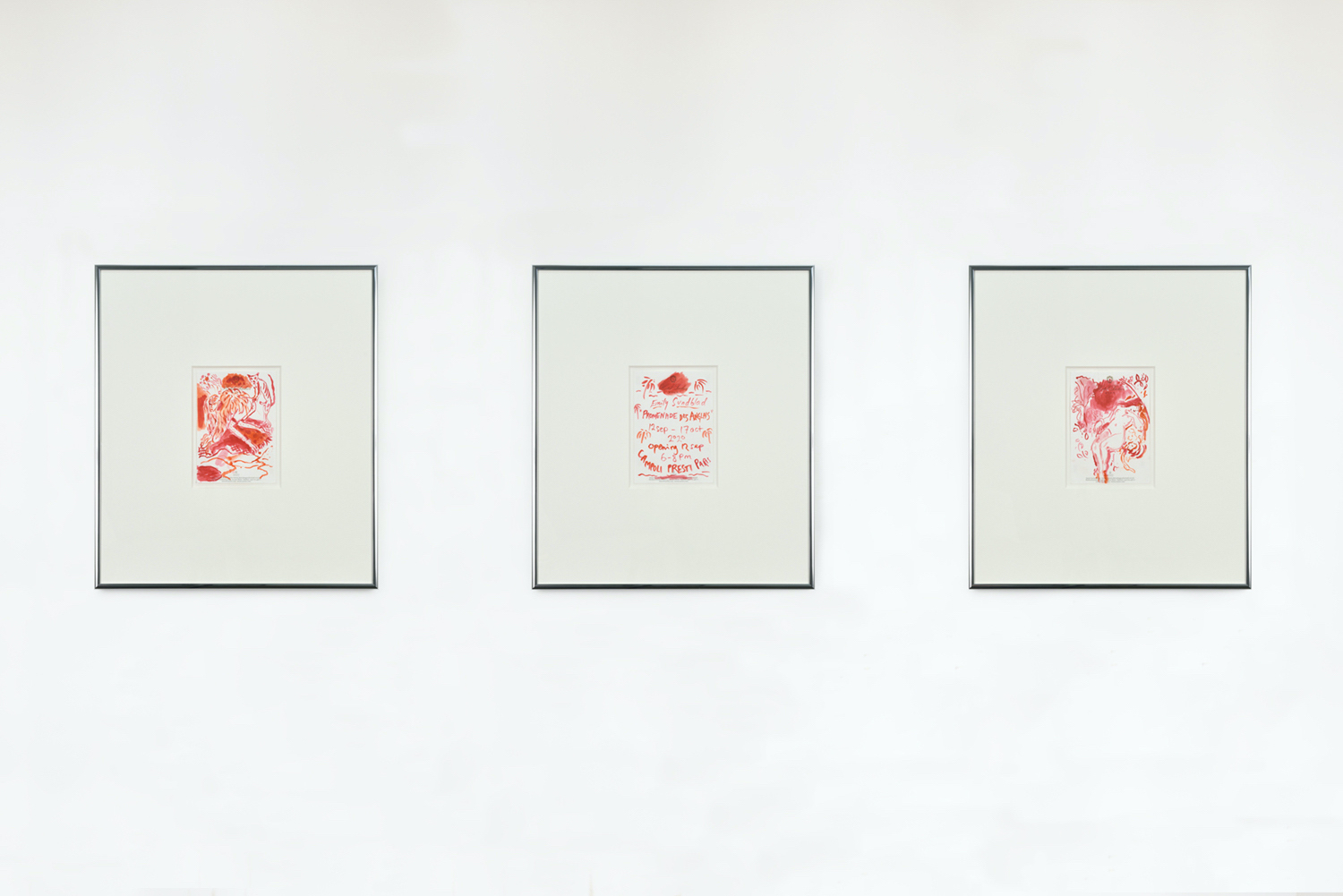

“Please accommodate and excuse the mess,” whispers Anna Franceschini in the heart of Paris, referring to the back cover of Il Salotto Cattivo. Splendori e miserie dell’arredamento borghese (Almanacco Bompiani, 1975). It is a tempting sort of nightmare, made of micro-architectural jewelry, violently scraping fingernails, and small engines exhaling and wheezing. Everything is whirring, murmuring, scratching: is technique a question of fussy precision or erotic perdition? Anna Franceschini’s solo exhibition “Il Salotto Cattivo,” held in the Parisian spaces of Campoli Presti, is a disillusioned homage to the splendours and miseries of the late nineteenth-century world. The artist seems to absorb through her very pores and neurons, both in terms of posture and craft, the nineteenth-century sources she so finely calibrates. So, it does not seem pretextual to glimpse in the filigree of her Salotto Cattivo a perpetual putting-in-movement of what Benjamin called the intérieur, the final “refuge of art” from the belligerent assaults of the commodity. Living, argues the Berlin-based intellectual, means first and foremost to leave traces: it is a praxis of overuse, fingering, and impressions, a pervasive yet invisible ritual of bodies forever altering the mundane objects they enter into daily contact with, such as cases, pouches, pillowcases, or linens.

The domestic space enclosed by Franceschini is not strictly an architectural membrane filled with furniture components of dubious taste or glorious trinkets awaiting lovely dust. Certainly, it can also be that. But, above all, her intérieur maléfique results in an environmental tension, a widespread high voltage that wants to dazzle. The immersive mechanism conceived by Franceschini, that is, a polycentric intelligence consisting of planchettes, self-propelled mannequins, vizard-jewels, and reproductions of irresistible props glittering from shop windows, cannot stop making traces. In the artist’s practice, perfecting the apparatus means jamming it, calibrating it to an unbearable parameter: the work itself results in an infinite tracing, a homogeneous desiring sprint that neutralizes itself into a Picabian paroxysm, while the host of the exhibition, the unaware customer, is in turn traced and tracked. By whom, exactly? Undoubtedly by the artworks, the genuine owners of this mediumistic boudoir. By joining forces, they have formed a coalition, reassembling into an independent labor union, and it is rumoured — but they are terrifically nonchalant in their programmatic grinding — that they want to sweetly haunt our dreams.

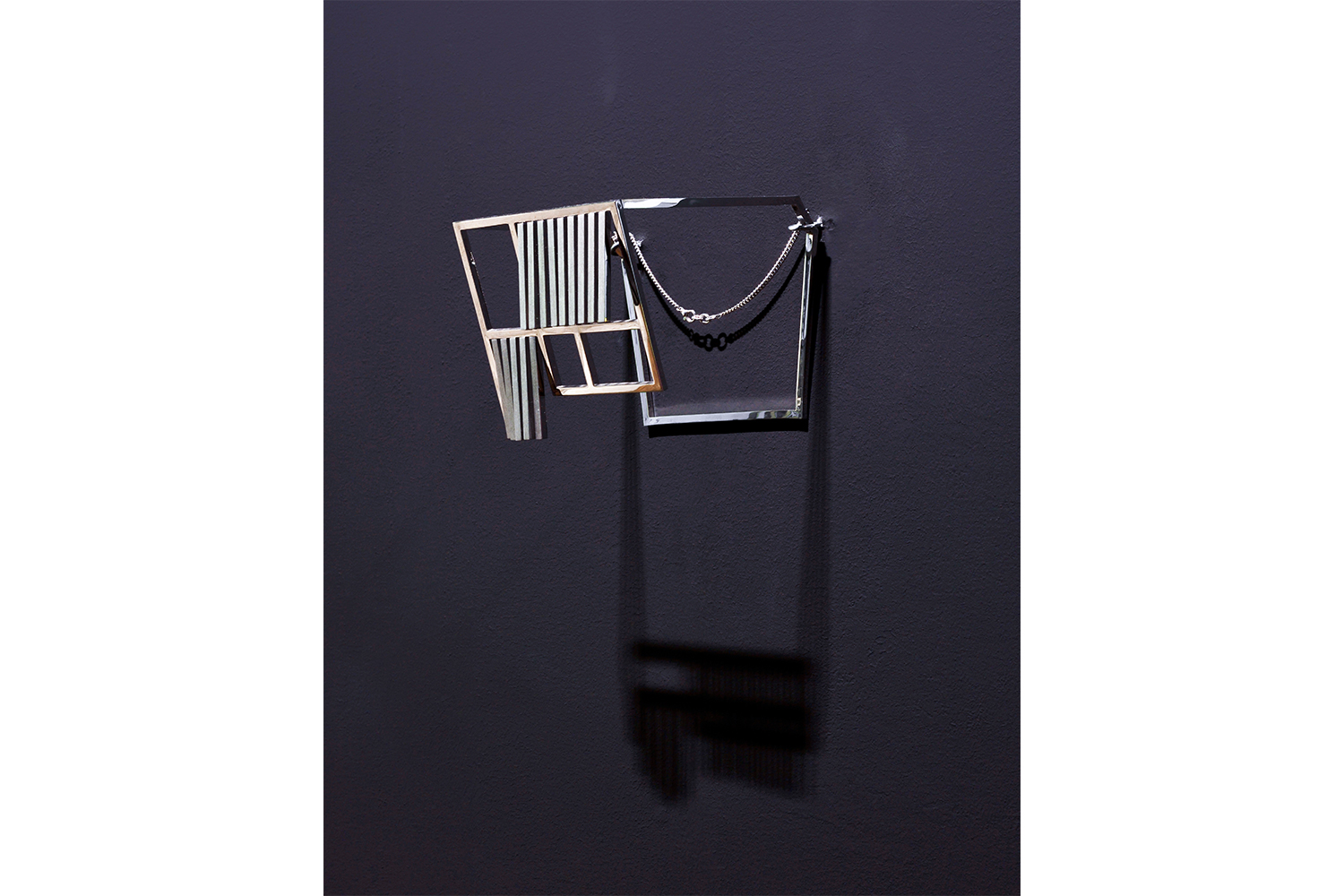

I have claimed that Franceschini has a nineteenth-century way of interpreting the artistic profession. The exhibition outlines a heartfelt tribute to a century in which empiricism and spiritualism exquisitely blend, where the collection of sensible data is implemented in the most unthinkable and eccentric research fields. Franceschini consciously plays the role of “time-wasting” inventor, clairvoyant medium, experienced window dresser, and precise metalworker. The Parisian salon is colonized by four specimens of planchettes — a rudimentary nineteenth-century instrument that records paranormal communications by translating the unconscious tremors of the hands on a wooden support, often heart-shaped — called Smooth Operators (2022). Whether secured on a refined bureau, laid on the floor, or hung on the wall, they proudly display their automatic soul: soft hands equipped with engines and thick cables relentlessly reiterate a codified gesture, rumbling in a whirl. Modern Times could not be more sensual… but also more disquieting. The triad of 3D (2022) photographic reproductions, overlooked by female mannequins of mother-of-pearl or jasper skins, haughtily attends the neurotic orchestra. Perhaps, to get the hidden messages propagated by such an inexhaustible network of whispering mēkhanē-girls, the host, suddenly heroic, should try on the galvanized wearable sculpture of Demonstrationraum (2022). Maybe, thus armed and relishing the aura of this modernist memento, the rebellious invitée can intercept the occult thoughts from the inorganic!

No doubt that the appointed victims of such hissing gear are essentially two: us, and the artist. Franceschini inhabits the vanishing point where things stay industrious, simply waiting for something to happen: a moment, her grasping hands, fingers of over-excited machines, lift us to touch a cosmetic sky. It is not that complex getting addicted to the dithyrambic rhythm of the gizmo. Surely, it should be dreadful, but you know, it’s all that rubbing… and those nocturnal fingers, opaque as the unknown from the deep universe, might end up caressing your heart too. A moment later, when you reawaken from the orgasmic hypnosis calibrated to the turning of the inner workings, you feel dazed and perhaps empty. The endless caresses of long velvet fingers reveal their recondite essence: a slow and obstinate process of removing the epidermis, a mutation of the support, a writing that exceeds its own code. In a strenuous attempt to reveal the reverse side of things, their obscene sheath, Franceschini declaims an ode to their being alluringly operational yet gloriously unproductive. Scratching is not just a matter of seduction but of resistance. L’intérieur est mauvais, vive l’intérieur!