A bi-monthly review of global art news from an admittedly fallible viewpoint.

The Latent Transformative Power of Writing

Unless the work of freelance journalists is fully “acknowledged, appreciated, and accounted for, there will be a steady erosion in pay and conditions for all,” reads Freelancers for Fair Rates, a 2021 report published by Australian union Media, Entertainment & Arts Alliance.

To achieve higher, fairer, and more equitable wages, freelance writers in the art industry have to describe the forces at play, but you can’t build a problem so big it becomes insurmountable. As Fredric Jameson argues in Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (1991), the more powerful the vision of some increasingly pervasive system the more powerless we come to feel. “By constructing an increasingly closed and terrifying machine,” he writes, theory and criticism can restrict the “impulses of negation and revolt” and foreclose the possibility of social transformation.

During a global pandemic and period of acute competition for work and long-term wage stagnation, successful collective organizing for freelancers will require writers to not only give voice to currents of resistance and imagine radical alternatives but also get on with the real work of organizing.

Freelancers: Microentrepreneurs, Individualized Copying Strategies, and the Uneasy Coalition with Full-Timers

Full- and part-timers need to collectivize as well, and in reality “self-employed” and “employed” are not exclusive categories. A lot of individual freelance arts writers hold full- or part-time jobs in publishing houses, museums and galleries, and the wider creative sector, though freelancers experience more extreme precarity than employed writers. Staffers are subject to similar low, stagnant wages, albeit fixed by contract, protected by minimum-wage legislation, and guaranteed at the end of every month. Full- and part-timers experience the same stress of crunch deadlines, particularly before going to print on a season’s issue, though without the feast-famine cycles of freelancing.

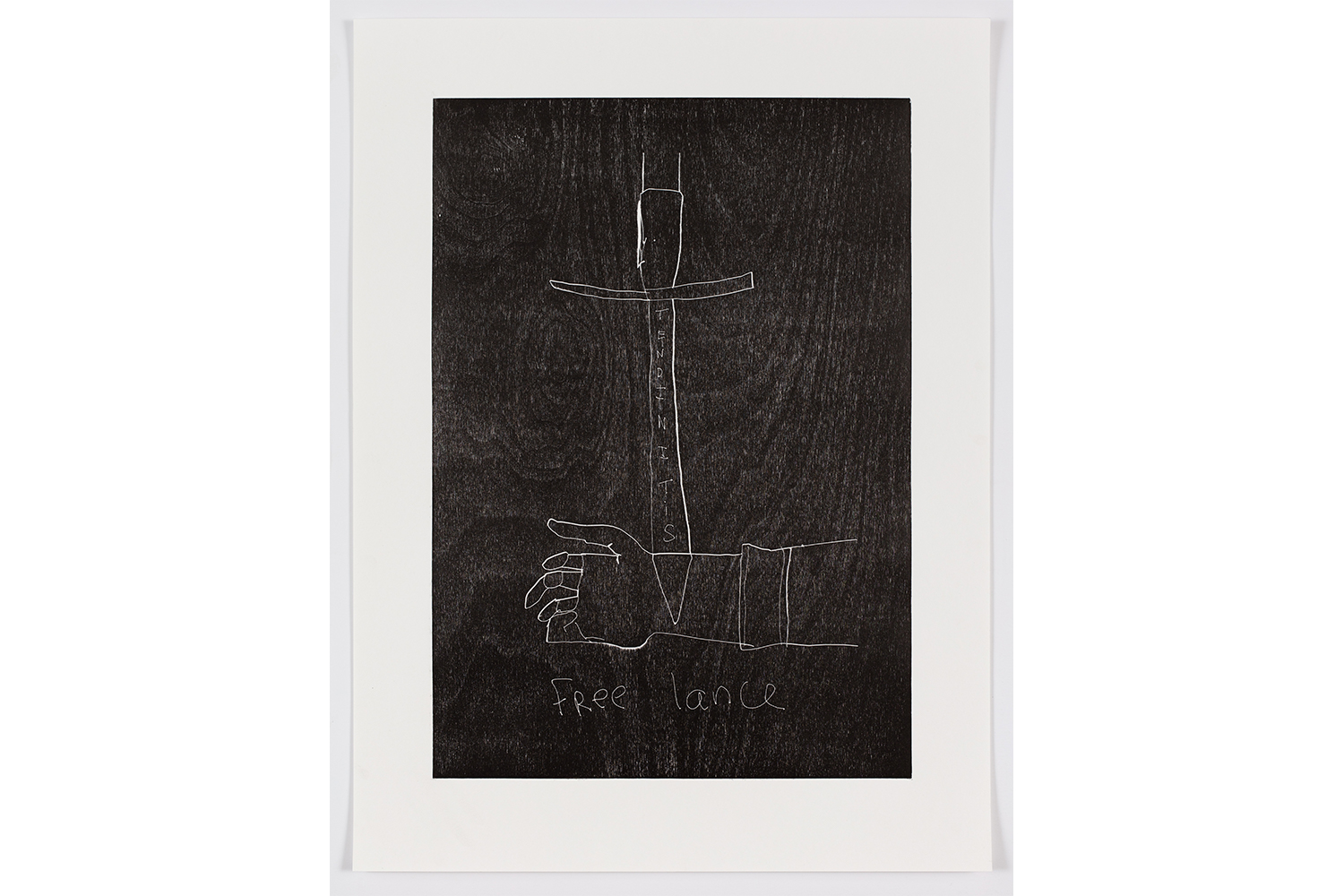

Freelancers are afforded high levels of creative agency and autonomy. As an arts writer, you’re free to pursue your own research interests, contribute to any magazine, and exercise near complete critical independence, almost entirely absent of managerial intervention from commissioning editors. However, work is temporary and intermittent, project by project, and only lasts the time it takes to complete the commission. Work comes in stop-go cycles, requiring intense, round-the-clock labor without weekends off, followed by irregular and unforeseeable periods of underemployment. Desperate, seemingly never-ending, you can’t switch off, take holiday; you’re constantly working to secure new work. Pay is usually only received on completion of the job, frequently late, sometimes indefinitely withheld, and, like artists, arts writers usually work for a fixed fee, occasionally a per-word rate, but neither accounts for time spent on research. Commissions are usually secured by shaky, informal email agreements, rarely by contract, far weaker in a court of law if you are denied payment and decide to take your case to trial.

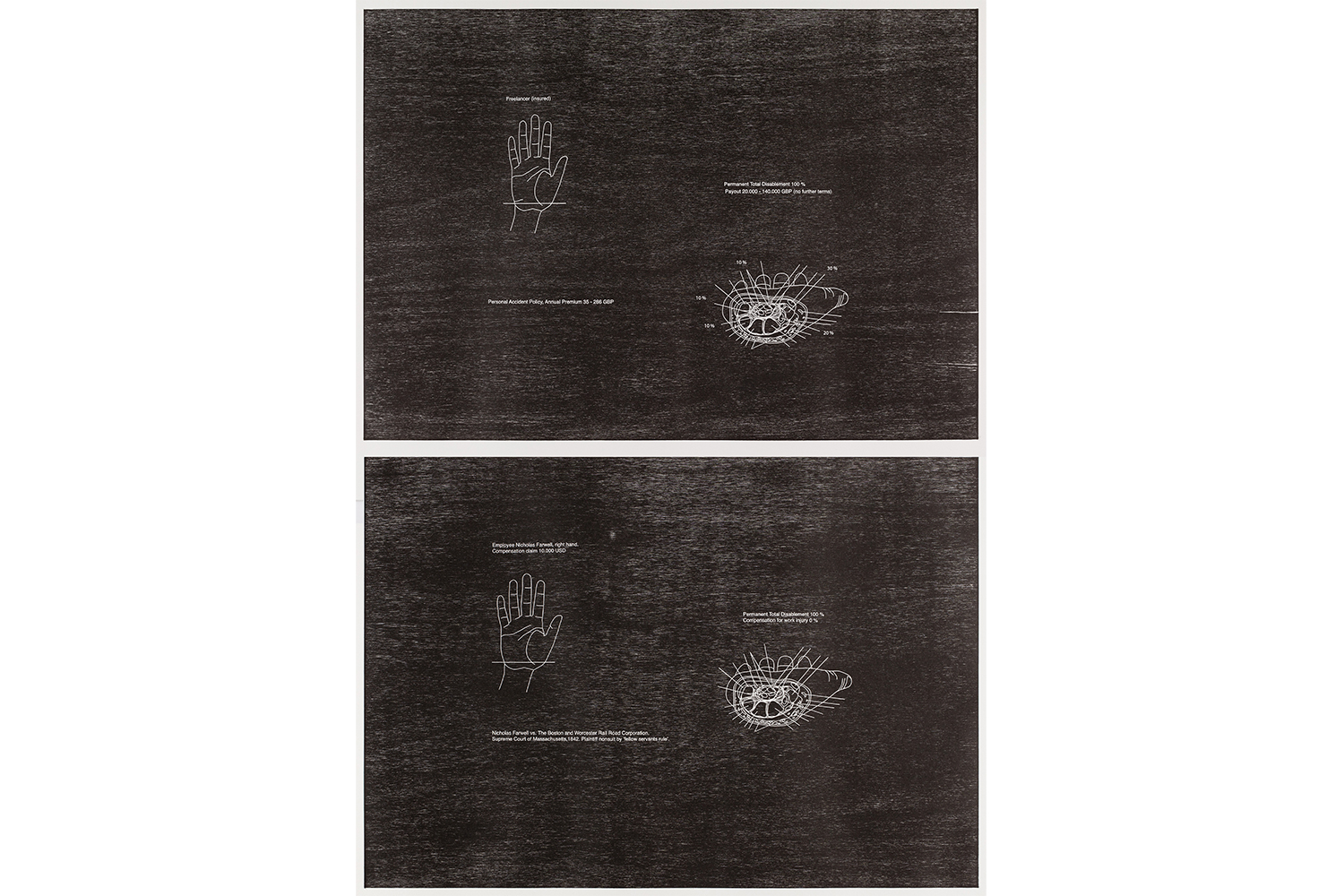

Freelancers are usually classified as “self-employed,” though their legal status varies from country to country. As set out in Heather Parry and Maria Stoian’s Illustrated Freelancer’s Guide (2021), in the UK, like other countries, freelancers have no minimum-wage protection, and no paid holiday, sick pay, or parental pay.

As Nicole Cohen argues in an article in Just Labour, “Negotiating Writers’ Rights: Freelance Cultural Labour and the Challenge of Organizing,” freelance writers face stagnant wages (falling over time with inflation), a hyper-competitive job market, a lack of legal securities, and work-from-home isolation, long before the pandemic. As a result, freelancers, across the creative sector, have been encouraged to think of themselves as entrepreneurs, develop highly individualized coping strategies, and view peers as competitors, significantly weakening collective solidarity.

The legal system codifies and reinforces radical self-reliance and entrepreneurialism in freelancers. The UK, for example, categorizes self-employed workers as “sole traders,” conceived by the tax authorities as a kind of small business owner. According to Her Majesty’s Revenue and Customs, a sole trader runs their own “business” as an individual, sends a tax return each year, and pays income tax. You keep all business profits after tax and you are personally liable for any business losses. In other words, you may exploit or fall victim to your precarious rights and protections but the state accepts no responsibility for you.

COVID Stimulus Funding: How the Law Unmakes Freelancer Rights and Protections

Across the globe, freelance writers in the art and culture industries have been hit hard by the pandemic and lack of government support. In 2020 alone, Oxford Economics estimated job losses of 287,000 in self-employed workers from UK creative industries, further increasing competition for commissions, and an international ProWriter survey (2020) found that 56 percent of freelance writers had no full-time employment to rely on if opportunities dried up.

Government stimulus funding has not simply highlighted freelancers’ existing precarity; it has actively unmade their rights and protections. As detailed by a 2021 European Trade Union Institute report, “Creative labour in the era of Covid-19: the case of freelancers,” access to funding for self-employed workers has been restricted by punitively discriminatory criteria. In Germany and Belgium, COVID financial support schemes required freelancers to prove loss of earnings of 60 percent, an arbitrary figure that meant individuals with losses of 59 percent received no support; the threshold is very high as well, particularly for arts writers who may derive a large proportion of their income from employed work. Elsewhere, to be eligible for UK self-employment income support required a tax return for the previous year, i.e., a proven track record of profit-making, and you had to derive 50 percent of your income from self-employed work. Anyone who became self-employed after April 2019 was excluded from the scheme, unfairly disadvantaging new, especially young, financially-unstable freelancers.

Rate Sharing: Suggested Rates vs. Rate Transparency

As the ETUI report says in its policy recommendations, freelancers require “universal, adequate, and easily accessible” financial support to alleviate the effects of COVID-19. However, transformative change will not come from top-down solutions, liberal panaceas, or “small claims courts for all.” Fair and equitable pay, real autonomy and control over working life, will come from the bottom up, getting organized, not from states that have continually stripped freelance writers of security.

Rate sharing enables workers to compare the range of wages the market offers and not only achieve higher, fairer remuneration for their time and labor but also identify and address pay discrimination. A successful example from the arts came from Art + Museum Transparency. Founded in 2019, the group created an editable, open-access online spreadsheet for arts and museum workers’ wages. With more than 3,200 entries, the database of hourly and permanent salaries reveals deep inequalities between the highest earners and the rest. (AMT later started an internship spreadsheet, showing widespread exploitation of unpaid labor.)

Some comparable resources already exist for freelance arts writers. A growing number of individual arts writers share achieved rates on social media. Another approach is peer-to-peer rate sharing, either online, often private email, or in-person, usually one-to-one or in small groups. However, both are limited in reach and impact. To encourage widespread, collective buy-in, access to rate-sharing resources needs to be completely unrestricted, like the Art + Museum Transparency spreadsheets.

The International Association of Art Critics (AICA) offers recommended rates. The UK branch has a minimum approved rate of 35 pence GBP per word, which is unrealistically high as a starting rate for art magazines and largely divorced from the current wage market. Moreover, AICA has no real power to persuade publications to adhere to their rates, and members aren’t required or even encouraged to reject commissions that fall below the minimum pay threshold.

The UK’s National Union of Journalists offers an online database of achieved freelance writing rates, including a wide range of fees for international art publications. The NUJ’s Rate for the Job is open to non-members though could be improved, firstly by monitoring users’ race, gender, and years of experience to assess pay inequality; and secondly, plotting publication rates over time to track stagflation.

Collective Organizing: Professional Associations vs. Unions

Rate-sharing discourages freelance writers to view their peers as competitors and instead begin to see each other as allies in a shared, mutually beneficial struggle, albeit fairly disconnected still. If writers in the art sector belonged to a united, collective organization, they would be in a far stronger position to demand better pay and working conditions. Again, various sorts of professional bodies already exist, some mentioned before. AICA, for instance, is a professional association set up to provide members opportunities to network, market their services, exchange work opportunities, and develop and showcase their skills as art critics, for example by competing in writing prizes (Flashback 8). Professional bodies like AICA essentially exist to give individuals a competitive edge. As Cohen writes in Just Labour, “With their mandate to help members become individually competitive, professional, and self-reliant, professional associations risk following the same logic employed by industry and neoliberal capitalism, which fosters flexible workers who can adapt to industry whim, who take initiative to upgrade skills and knowledge, picking up slack from companies and from the state”.

By contrast, unions seek to build collective power and engage in collective bargaining, a process by which groups of workers negotiate with their employers to improve pay and conditions. There are also various national and even some international journalist unions, though arts writers perhaps share more common experience with artists than journalists and media workers. Artists deal with the same institutions and funding bodies in their professional life. For example, artists and arts writers can apply to Arts England Council for the same Developing your Creative Practice (DYCP) grants. However, many artist unions are only open to individuals practicing fine art, again leaving arts writers stranded, without representation.

Where AICA is narrowly focused on a single, very specific type of art writing, efforts to organize freelance arts writers will have to span both craft and industry, and incorporate a range of arts writing, editing, and publishing professions: critics, catalogue editors, contributors to academic journals, proofreaders, social media producers, interpretation writers in galleries and museums. Anyone who writes in the art industry.

Appendix: Rates Resources, Union Links & Reading Recommendations

Rates Resources

• National Union of Journalists (NUJ) (UK): Rate for the Job

Union Links

• Freelance Journalists Unions: Media, Entertainment & Arts Alliance Freelancers (Australia); European Federation of Journalists Freelance Experts’ Group; National Writers Union Freelance Solidarity Project (US); Canadian Freelance Union; National Union of Journalists London Freelance Branch (UK); Industrial Workers of the World Freelance Journalists Union (US/international)

• Related cultural solidarity collectives: Cultural Workers Organize (Canada); Precarious Workers Brigade (UK); and Migrants in Culture (UK)

• International Federation of Journalists (IFJ): Journalists’ trade unions and associations by continent/region and country

Reading Recommendations

• “The Bare Minimum Manifesto,” Bare Minimum Collective (2020)

• “Against Artsploitation,” Dana Kopel, The Baffler (2021)

• “Hours against the clock: on the politics of laziness,” Lola Olufemi, Autonomy (2021)

• Tereza Stejskalová, Barbora Kleinhamplová and members of the Precarious Workers Brigade on Precarity, Precarious Workers Brigade (2014)