“Listening In” is a column dedicated to sound, music, and listening practices in contemporary art and its spaces. This section focuses on how listening practices are being investigated and reconfigured by artists working across disciplines in the twenty-second century. This year the column is curated by Barbara London and explores how artists continue to investigate sound by incorporating up-to-the-minute software and electronic apparatuses to their practice. The best sound artwork takes its audience on an inspiring journey, one that offers fresh insight into what it means to be in the world, construing something animate and distinct by means of inorganic tools. It is through the tension between the haptic and the neutral that artists and observers discover new experiences.

As a curator and writer based in Manhattan, I track art that thrives on the border between disciplines and defies definition and speculation. In this spirited world out on the periphery, artists have room to breathe and create work that often moves freely between performance, installation, sculpture, and computer code.

For years I’ve pursued sonic art by artists whose careers may have begun in music, film, performance, painting and sculpture, electronics, or even literature. Their hybrid practice transgresses both the concert hall and the white cube gallery. Sound art’s diversity and intangibility makes it difficult to pigeonhole. Whether improvisational, precisely composed, software-derived or instrumental, object-oriented or environmental, sound artwork will incite as much as it inspires.

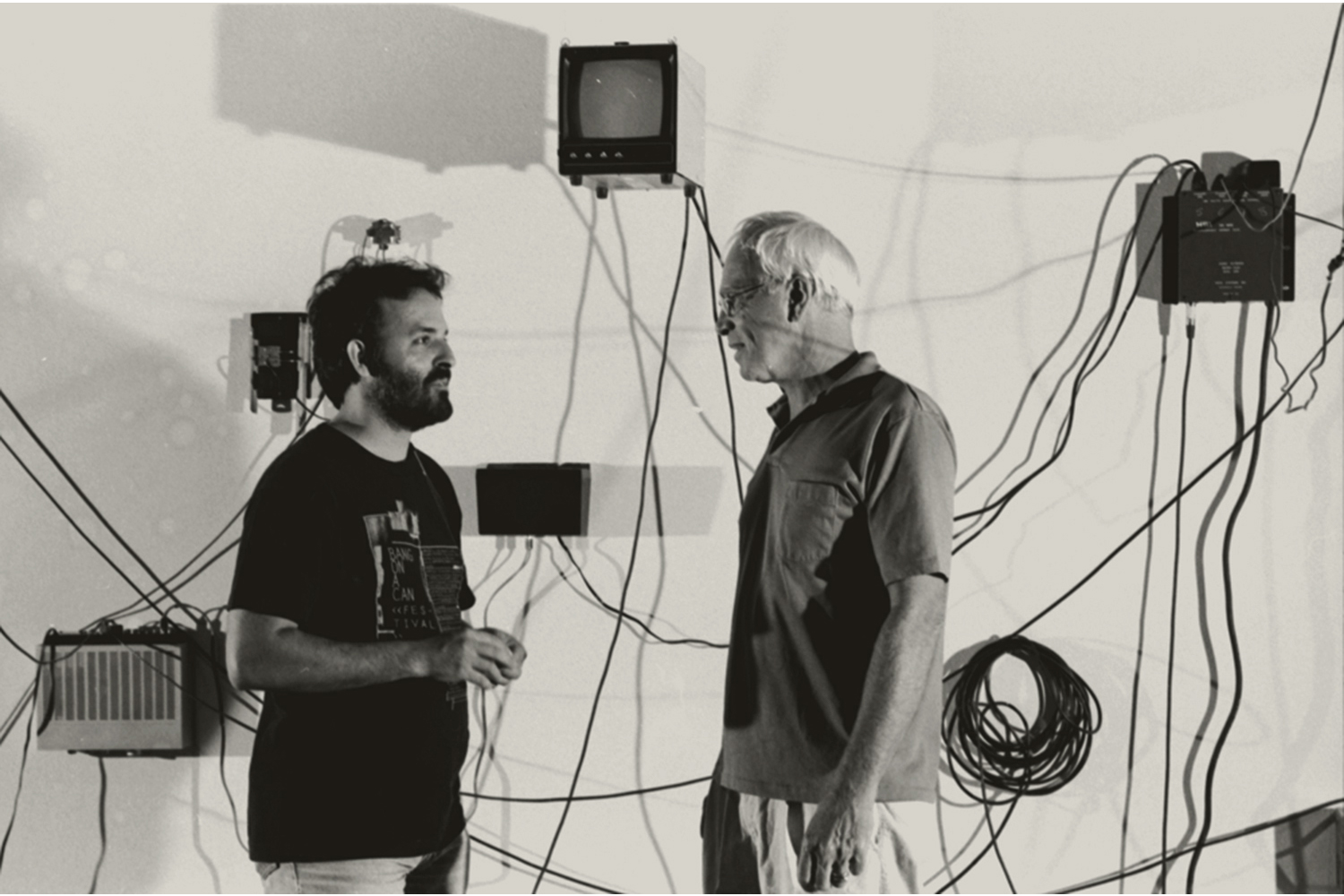

When COVID turned in-person events and travel into near impossibilities, my research moved online. I located texts to read and recordings to experience, and initiated conversations with artists in Zoom. Albeit stimulated and productive but feeling restless, this past winter I relocated temporarily to Miami. Straightaway I dove into the local scene, eager to know what was happening in a city with good weather, generous art patronage through the Knight Foundation, and seemingly ample opportunity for artists. During my quest, one name kept coming up: Gustavo Matamoros. The prominent experimental artist wears multiple hats as an indefatigable composer, artist, collaborator, impresario, and community organizer. When we met in his studio, I asked what was behind his music and sound installations, and how he became a catalyst and instigator of events in Miami.

Sound in Life

Matamoros explained that he’s been exploring “sound in life” since childhood. It all began in Caracas, where he was born in 1957. Being dyslexic and finding it difficult to read, his survival tactic involved listening carefully. He would make visual connections to the ambient sounds he heard at home, in the classroom, and out on the street. During childhood the world opened up as he spent hours playing with a short-wave radio. Uninterested in the voices of people speaking in unfamiliar languages from the other side of the world, he fixated on the ethereal electrostatics that seemed to arrive from outer space. It isn’t surprising that years later he took up the musical saw, a theremin-like, eerie-sounding acoustic instrument. In the 1990s he even formed a musical saw quartet, SEE, with Ryan Agnew, Ulrike Heydenreich, and Stephanie Lie.

From Venezuela to the US

Matamoros left Caracas in 1977, in order to pursue his interests in computers and music. He entered the Berklee College of Music in Boston, but stayed only a few semesters. It was long enough to connect with the experimental composer-oboist Joseph Celli, who broadened Matamoros’s ideas about what “new” music could be. While in Boston, he saw a lot of movies, becoming interested in composer Jerry Goldsmith, who wrote the film score for Chinatown. Gustavo was inspired by the way music and the noise within a film — dialogue and action — are what amplifies a story.

Finding Boston’s long, freezing-cold winters unbearable, Matamoros transferred to the University of Miami, with its warm weather and strong music department. He graduated with a degree in music theory and composition, as he meanwhile maintained his interest in computers.

In 1983, Matamoros met John Cage during a three-day event organized by faculty and students at the University of Miami. Later, in 1985, he and his fellow music students founded the Composers Alliance, a group that invited avant-garde composers to the university as guest speakers. Eager to broaden their own horizons, the group straightaway invited Cage back to visit. After spending several days in dialogue with the unassuming thinker, Gustavo determined it was a hands-on exploration of music he was interested in and decided to become a composer beyond the walls of academia.

Development as a Composer/Sound Artist in Miami

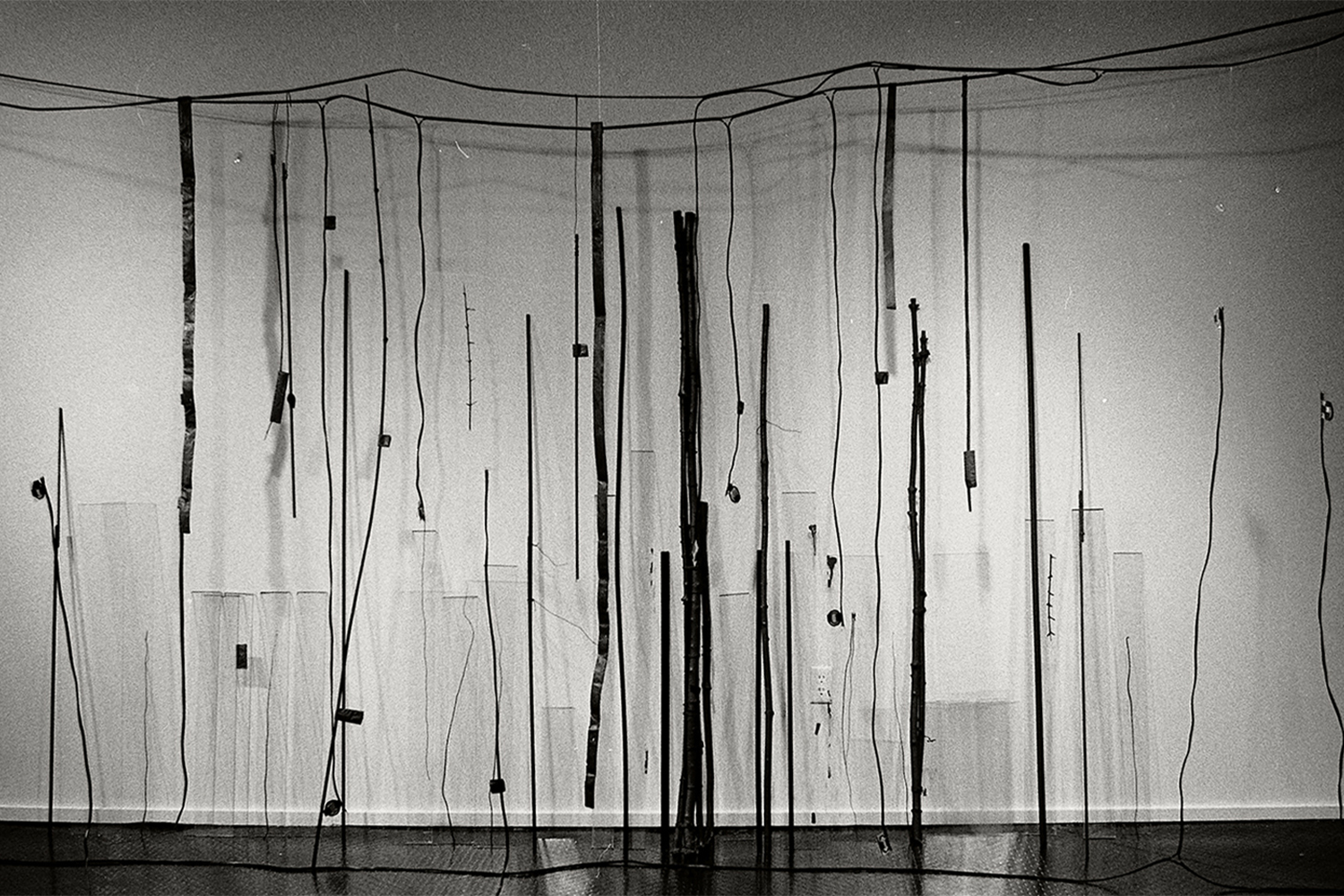

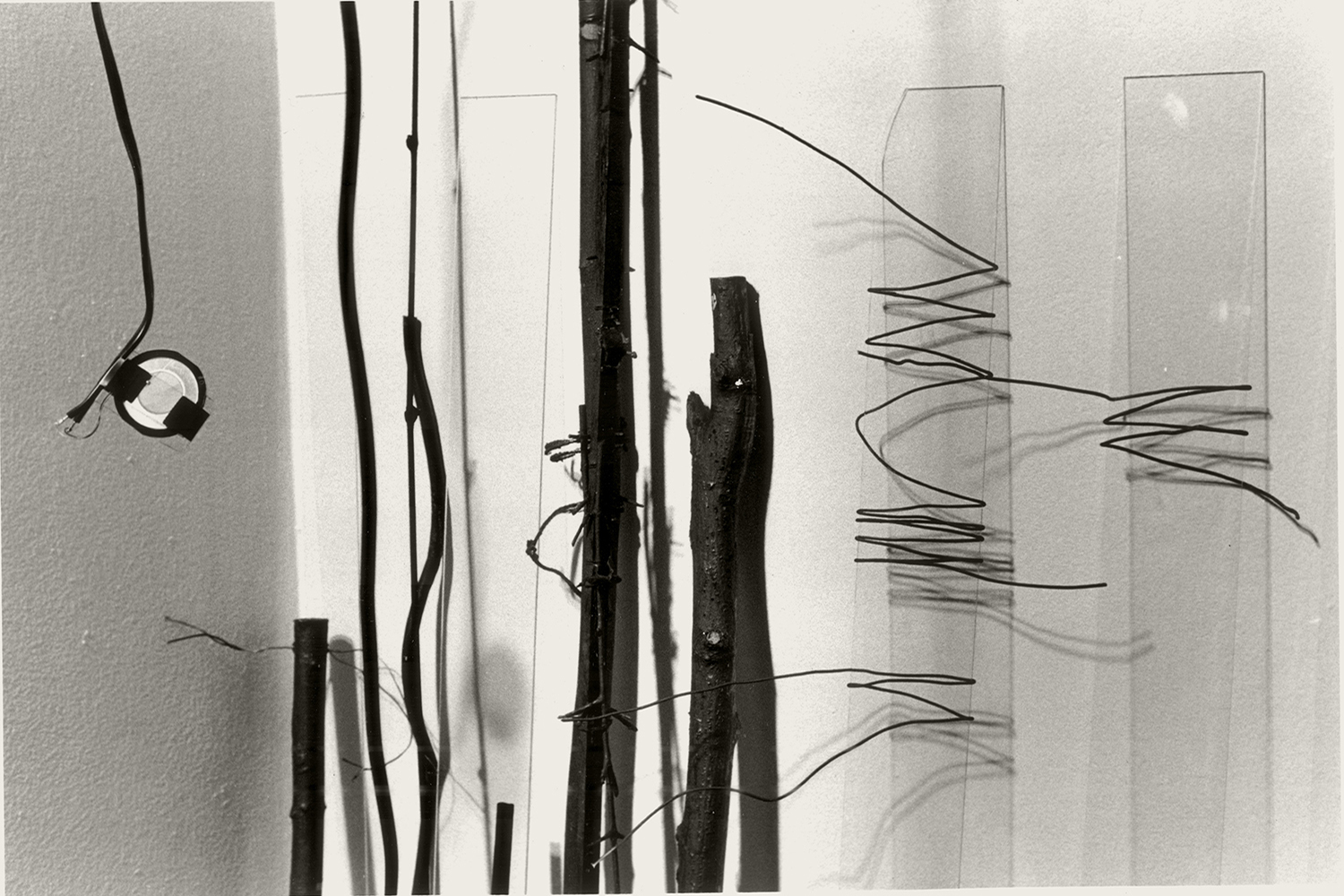

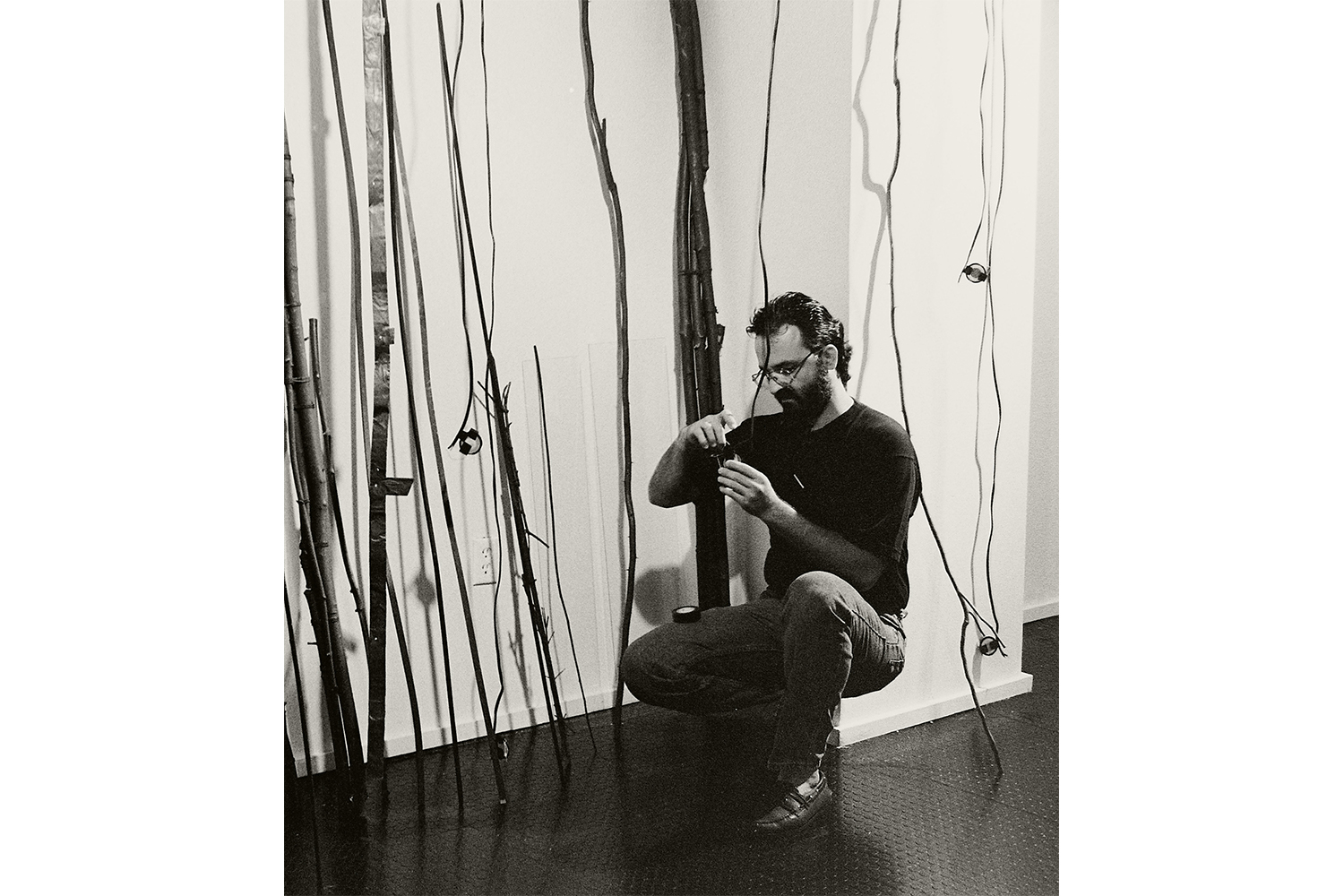

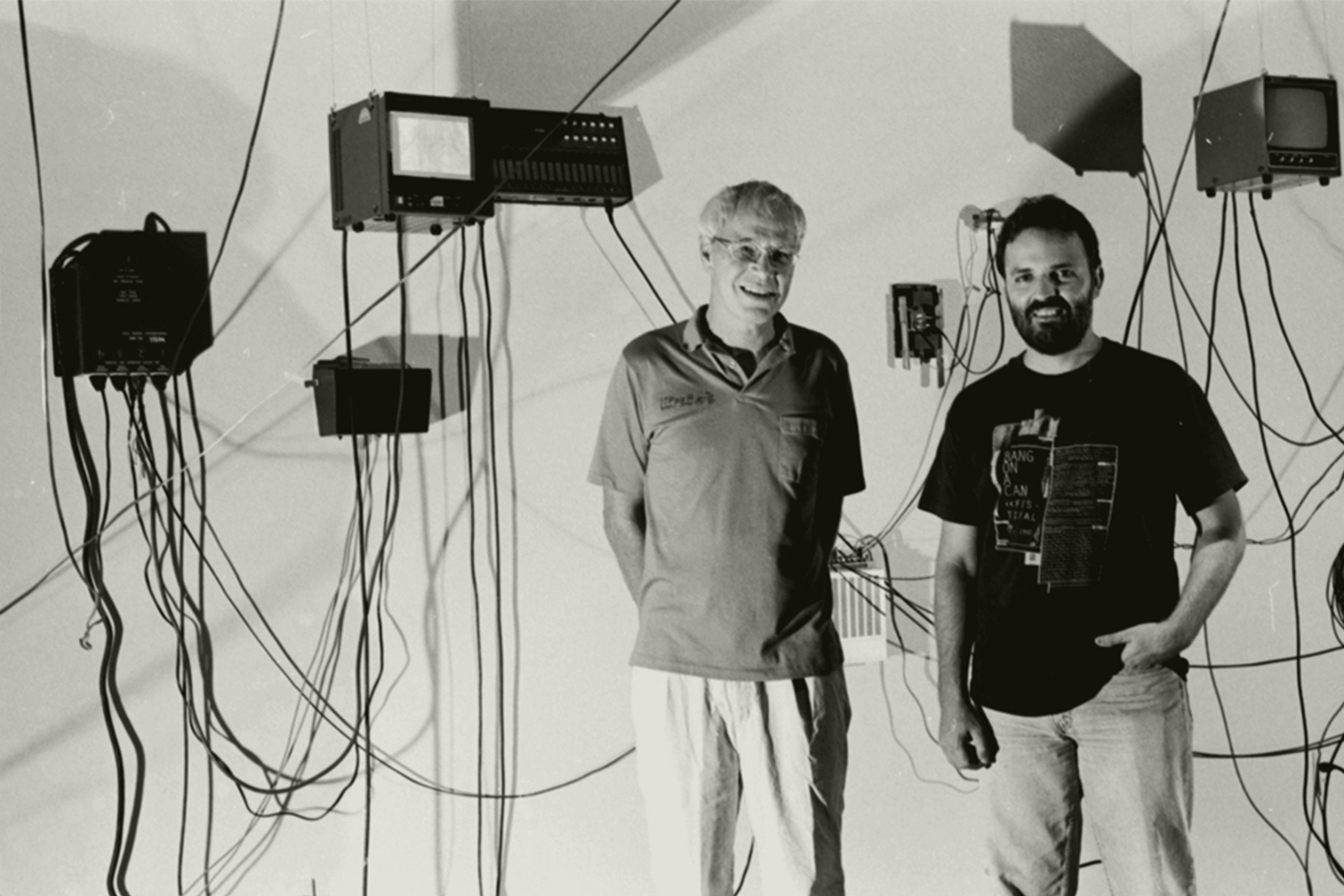

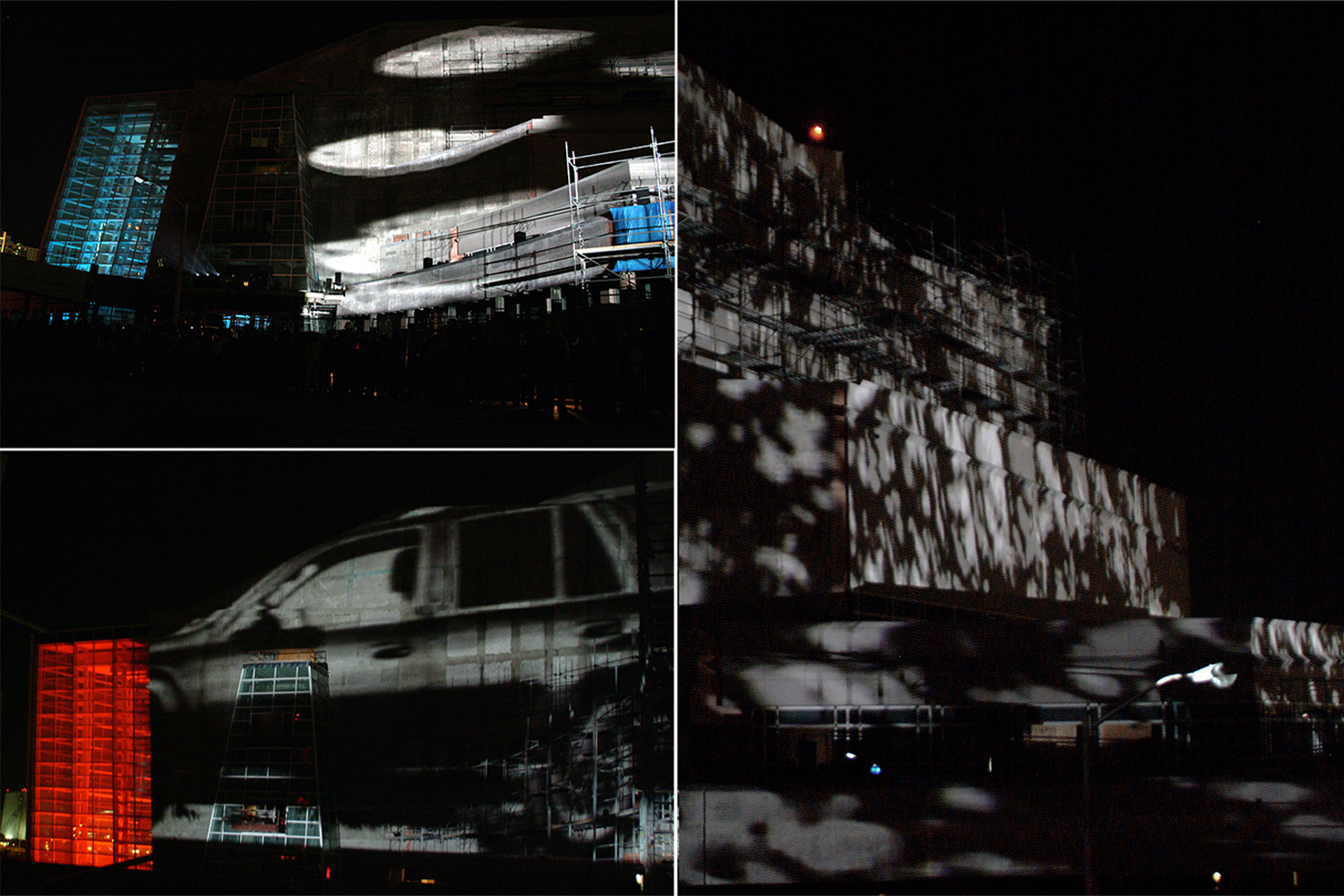

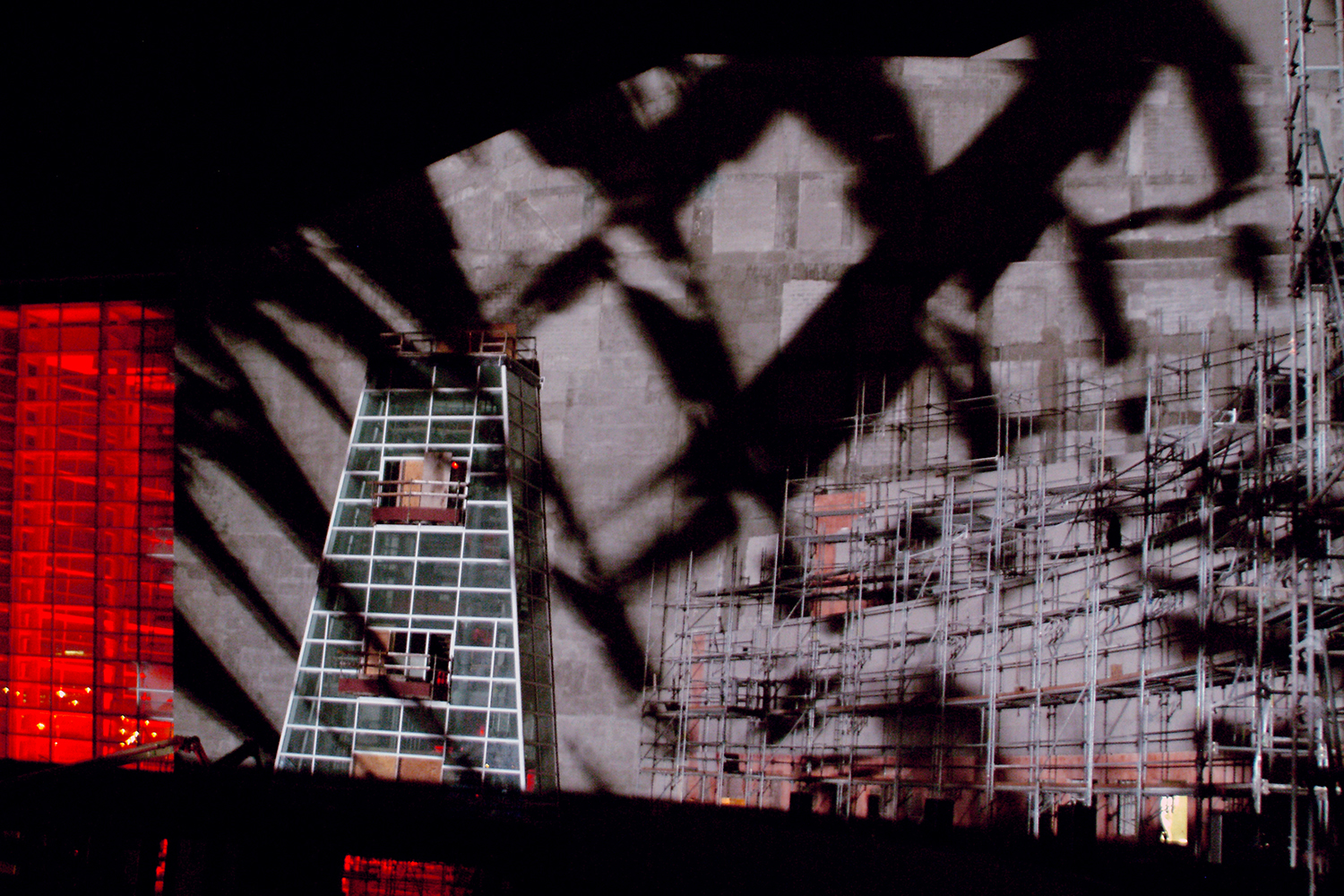

In 1985, Matamoros connected with the electronic composer Russell Frehling, who had studied music with Robert Ashley and had recently moved to Miami. A few years prior, Frehling lived in Japan and worked with Greenpeace, developing an underwater sound fence that kept dolphins out of commercial fisherman’s nets. In Miami, Frehling pursued his underwater sound instrument, and taught Matamoros a lot about how to work with sound and space. Frehling shared his belief that the critical issue is how sound functions in three dimensions. Sound’s physicality is where shape, texture, density, and arrangement in space become the objects of reflection in an environmental sound installation. By distilling from the surrounding ambient soundscape, complex waveforms and natural resonances are put in a dynamic relationship with their environment. The observer is given an opportunity to respond more palpably to the sonic material and the space it occupies. Frehling articulated ideas that Matamoros had already been pondering.

Eager to pursue his career as a composer within the community, in 1989 Matamoros founded the three-day Subtropics Festival as a way to introduce local sound practitioners to experimental composers such as Cage, Earle Brown, Morton Feldman, Alvin Lucier, Ashley, Pauline Oliveros, and Alison Knowles. Subtropics generated a lively exchange of ideas among attendees, including students, and it gave Matamoros an institutional footprint within Miami. Over the years, as Subtropics evolved and incorporated more sound and intermedia art into its program, the Bass Museum of Art and other public institutions came forward and offered to host his own work and his festival events.

Electronic Composer

Matamoros’s multitasking career includes that of electronic composer. In 1990, he and Armando Rodriguez Ruidíaz founded PUNTO, an ensemble committed to the performance of works that are conceptual and experimental, with roots in Fluxus. PUNTO utilized new and old technology to develop aural and visual materials that conveyed the processes and ideas inherent in each work. In 1991, PUNTO staged the first full-evening Fluxus concert in Miami’s Cameo Theater, with guest artists including Frehling, Frederic Snitzer, and Robert Gregory, performing a program based on research conducted at the Ruth and Marvin Sackner Archive of Concrete and Visual Poetry, then located in Miami Beach, now based at the University of Iowa.

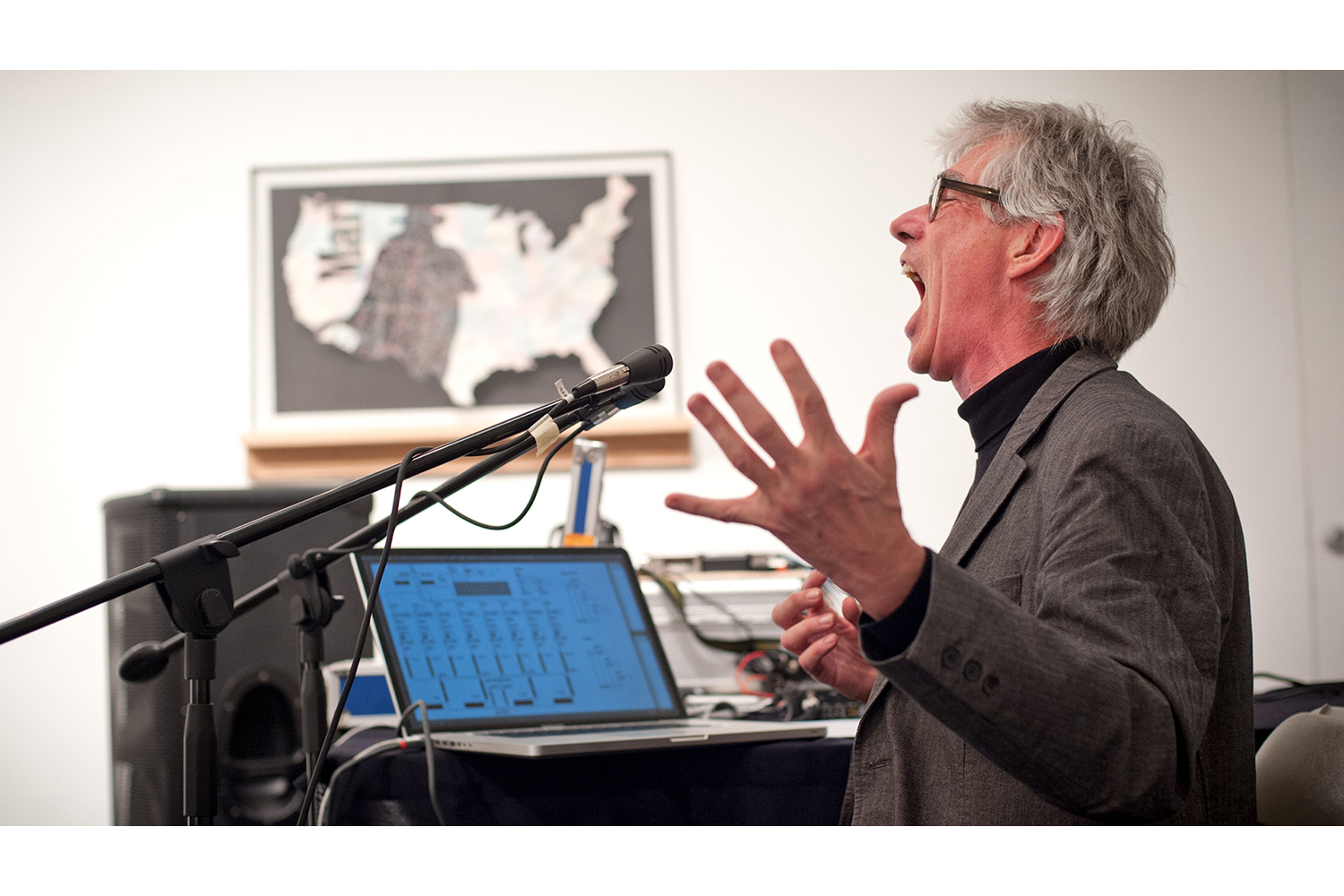

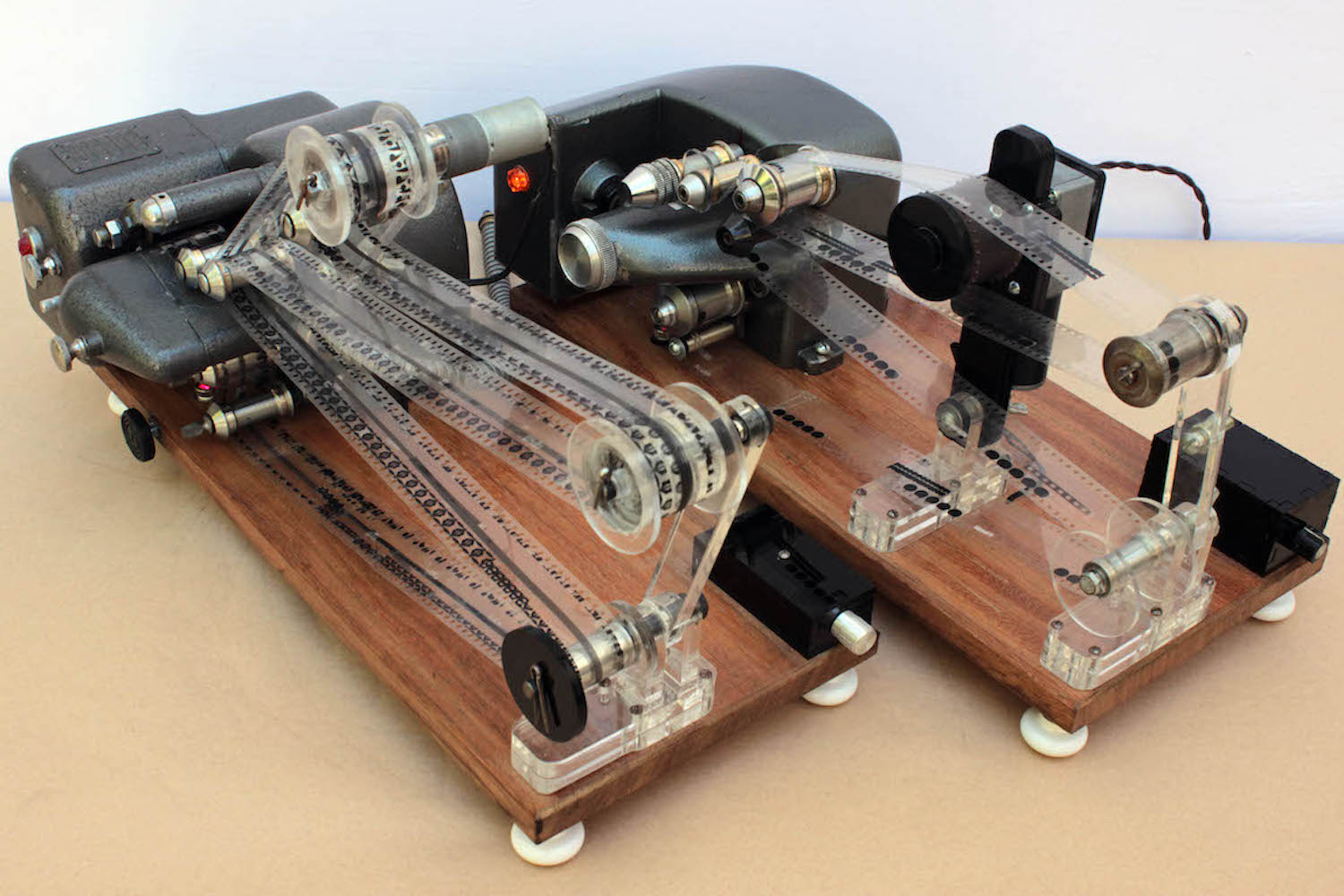

Matamoros has described his electroacoustic music as a kind of karaoke-like live performance, as an “acoustic instrument” laid over a composition on tape created in the studio. The way it worked with Matamoros’s Portrait: Bob Gregory (1990), the poet read over a prerecorded composition, inserting words and pronouncing them in response to what he heard on the tape in terms of timbre, tone, and pacing.

New Music America: Miami and the Listening Gallery

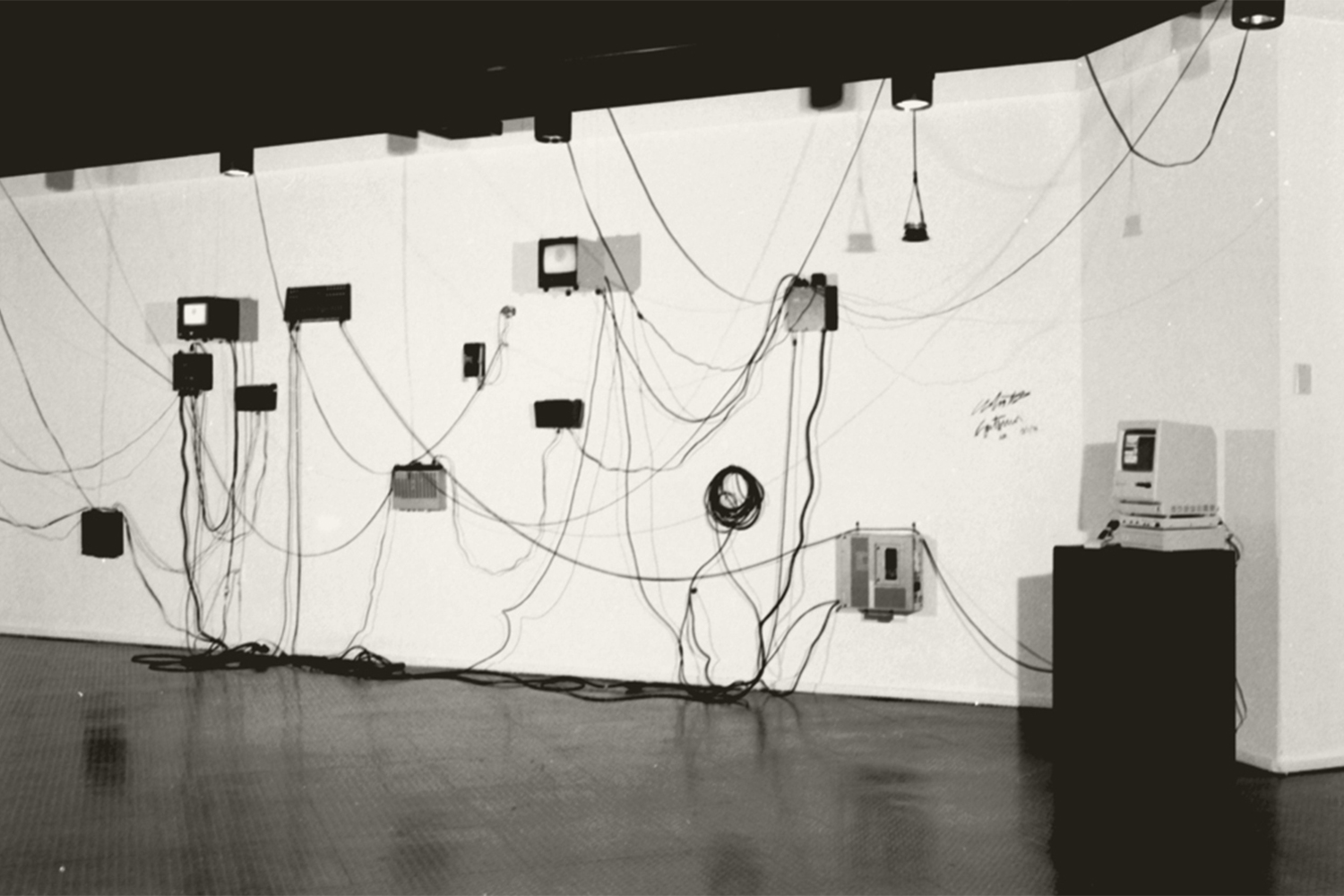

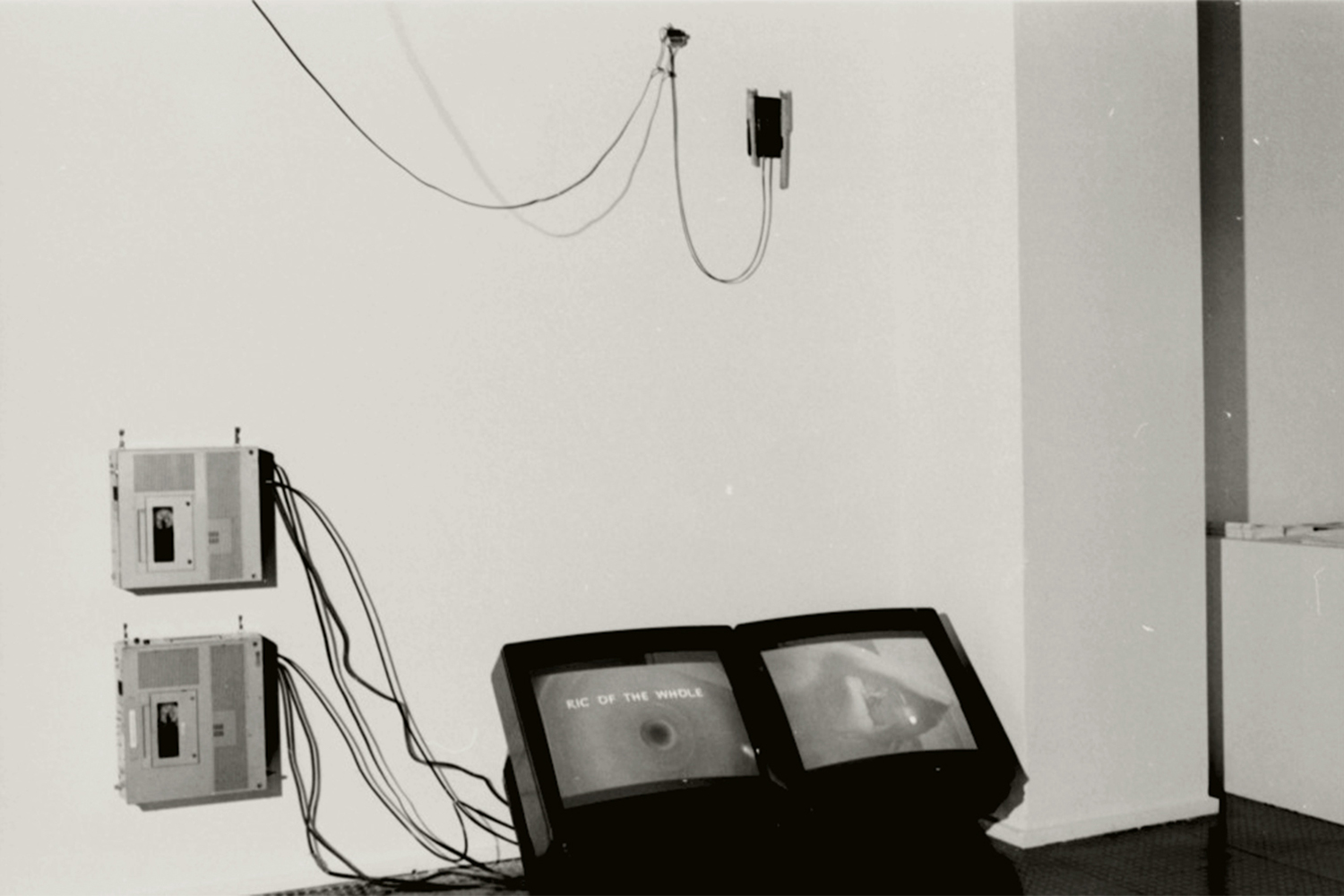

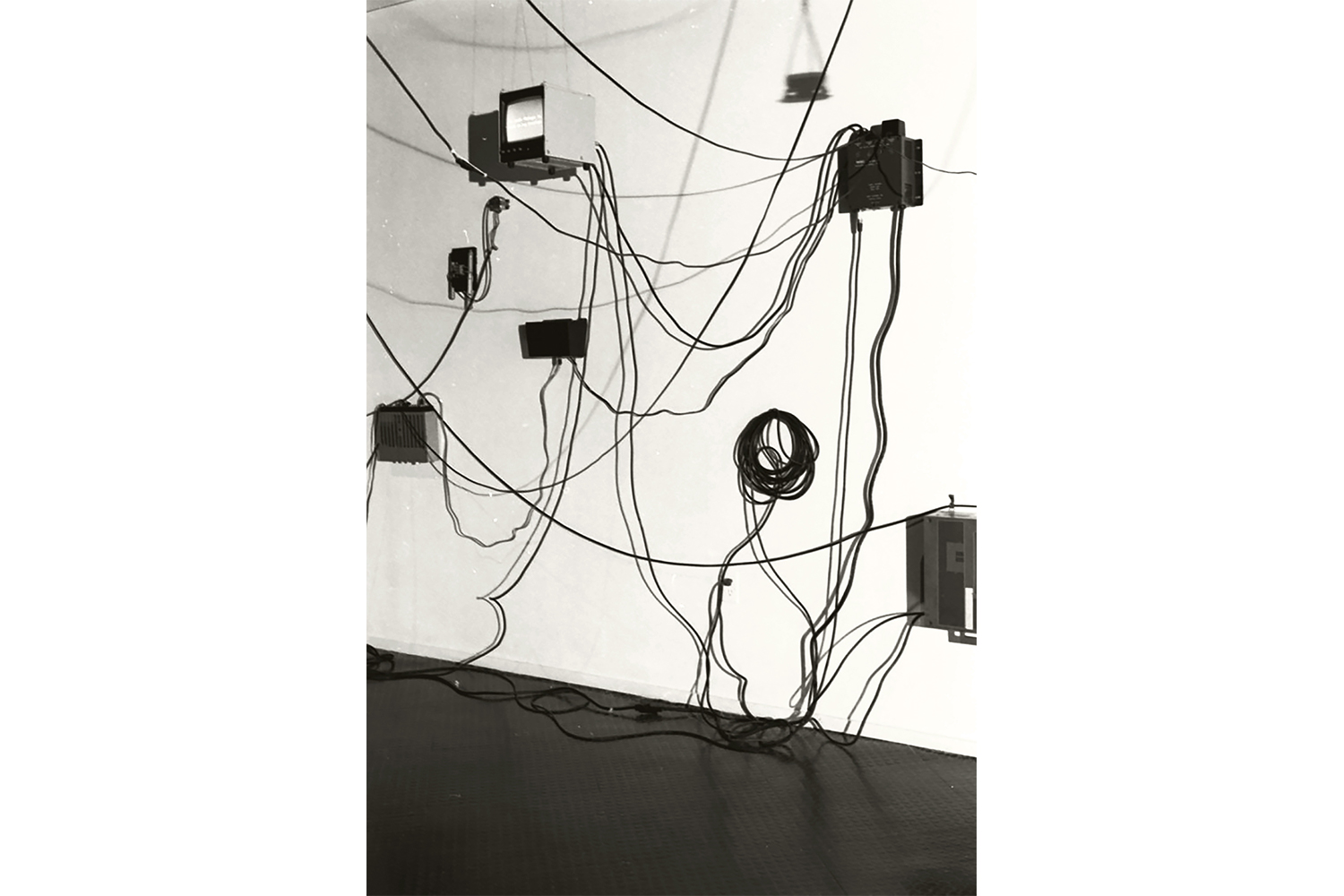

Wearing what evolved into his Subtropics hat, Matamoros became the technical coordinator of a special edition of the New Music America (NMA) festival when it took place in Miami in 1988, organized by composer Celli and choreographer Mary Luft, through her company Tigertail Productions. (Founded nine years earlier in New York, the nomadic NMA festival was held annually in a different North American city, where up-to-the-minute new sounds premiered and emerging sound-art trends were discussed until it formally ended in 1990.) As technical coordinator of Miami NMA, Matamoros enjoyed his position of figuring out the technical nature of experimental works by more than one hundred international artists presented in Miami.

Matamoros went on to launch the Listening Gallery, a sonic oasis located on the pedestrian shopping street Lincoln Road in Miami Beach. Situated in a building owned and occupied by the Art Center of South Florida (Oolite Arts), Oolite wanted to lure the thousands of daily passersby into its artist residency spaces. Matamoros obtained a grant from the Knight Foundation and opened the Listening Gallery, using Subtropics as his umbrella. Operating by stealth, he installed loudspeakers around the facade of the entire building, under the awnings above the entrance. Intrigued pedestrians stopped and listened to Matamoros’s and invited artists’ new site-specific works, each of which stayed up for six weeks. The project ran nonstop from 2011 to 2015, until the organization sold the building — a familiar urban story.

Field Recording and the Deering Estate

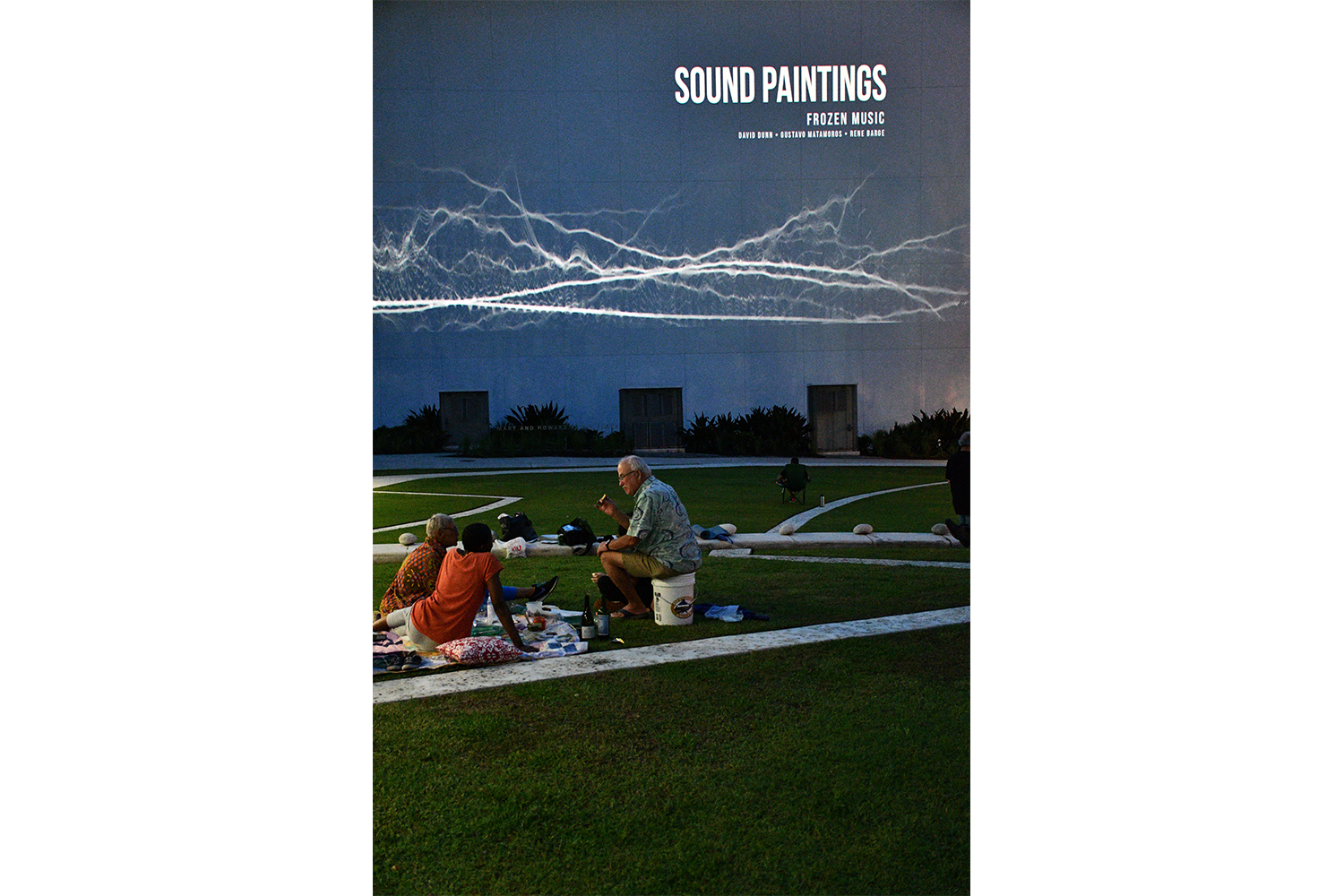

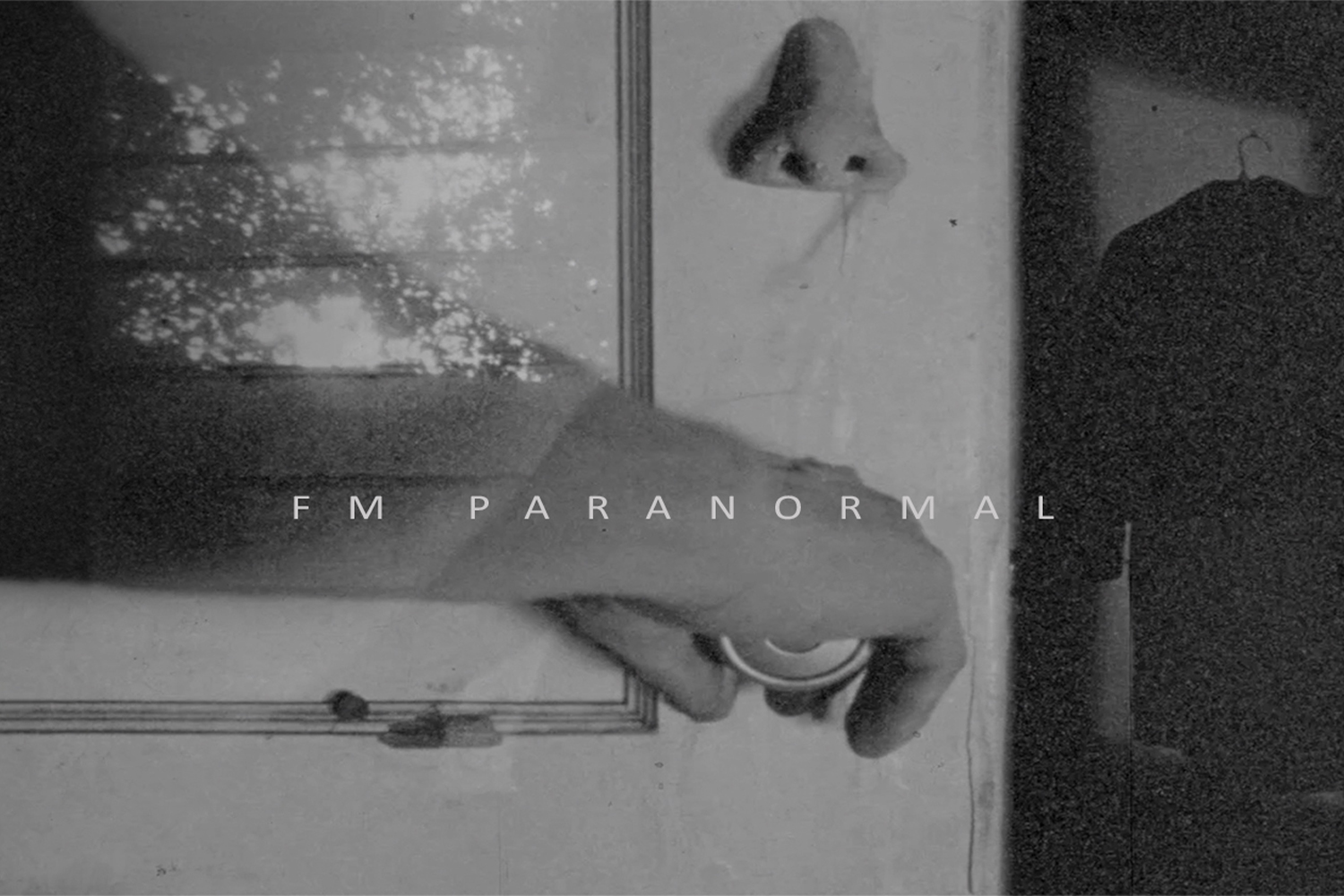

Over the years, Matamoros has made field recordings in such places as the Everglades and in local buildings, including the Vizcaya Museum and Gardens, the former waterfront estate built by James Deering in 1916. Gustavo developed another interior work in another early twentieth-century mansion, the Deering Estate’s Richmond Cottage, which purportedly is haunted. He made ultrasonic contact microphone recordings of sounds that were occurring at frequency ranges between 20,000 and 96,000 hertz. Matamoros transposed the faint sounds down a few octaves to within the human ear’s normal audible range and amplified them. The eerie sounds became the raw material for the Paranormal performance he made with the Frozen Music ensemble (David Dunn and Rene Barge), his frequent collaborators. The performance morphed into a sound installation, orchestrated to bring out and activate the natural acoustics inside the wooden Richmond Cottage.

Recently awarded a new grant from the Knight Foundation, Matamoros has a yearlong residency in the Deering Estate’s theater, which will be his laboratory throughout 2022. His new research will result in several site-specific immersive installations that may combine prerecorded paranormal sounds with local myth, drawing on archival materials from both the Deering Estate library and the Subtropics collection. The project will have multiple outcomes. I heard one iteration on a balmy night in February, a magical sound composition discreetly installed within the luxuriant park of the Deering Estate.

This year Matamoros also has a residency at the Florida International University (FIU) North Campus Library. Over the coming months, he will interact with FIU students and faculty to collaborate on projects that incorporate marine science, journalism, and art, and will develop a permanent Ambisonic audio work for the University’s new i360 theater, which has a screen in the round and a full-sphere surround, Ambisonic sound system. Matamoros will draw upon his Audiotheque, the thirty-channel sound system he devised in 2018 for the ArtCenter South Florida.

Looking Forward

In South Florida the future is bright for sound artists, including Matamoros and recent arrivals Richard Garet (from New York), Alba Triana (from Bogota), Yucef Mehri (from Venezuela), and José Hernández Sánchez (from Spain). Miami offers a wide range of venues that are dedicated to experimental art. I’ve encountered sound art at the de la Cruz Collection; at the small Flowerbox Projects gallery, founded by artist Brian Gefen; at the MUD Foundation; at the Bass Museum, with a witty work by Naama Tsabar; and at the Museum of Art and Design, where Director Rina Carvajal has her eyes on the ball, in the same way as Alex Gartenfeld does at the ICA. A number of artists have long-term workspace through the residency program at the Bakehouse Art Complex; while others have short-term space at the Fountainhead residency program, where this month New Yorker Nate Lewis is developing a new series of sound and video works.

As John Cage often explained, an artwork isn’t completed until it’s activated by an audience. Today Miami is an excellent location for artists poised to develop and run with new ideas. I encourage everyone to stay tuned!