In Greek mythology, Momus is the figure who embodies satire. Cancelled from the company of the gods for being a kind of divine edgelord, Momus never let the lack of gainful godly employment stop him from plying his trade. Satire was a durable enterprise, after all. Momus features in the writings of Aesop, and in Roman comedy, and so despite the efforts to banish him, he somehow became a global brand. He’s been less visible in recent years, perhaps due to the advance of a culture that produces a reality that renders satire superfluous, but those familiar with his signature may see his work in the art world’s latest big-top attraction, the Amazing NFT. The Non-Fungible Token is often billed as a potential means for artists to escape, at last, the enforced precarity of art-world gatekeeping, and to create sustainable incomes on their own terms. The ubiquitous acronym of the term, once set loose in the art world, was swiftly shortened to “nifty,” almost as if self-satire were the goal. Nifty, with its connotations of novelty and ephemerality, is an ironic moniker for an instrument purported to bring stability to the lives of artists. Somewhere, surely, a god is laughing.

The technology behind the NFT, by now, is familiar to many; it is a specific location within a blockchain that directs to a given file. The file in question can be essentially anything, but it has become a byword in the art world for unique digital artworks that offer the allure of scarcity and the discursive veneer of tech-savvy futurity. The sale at Christie’s of Beeple’s Everydays: The First 5000 Days (2021), for the Redditor-friendly price of $69 million, earlier this year signaled the beginning of an inevitable digital gold rush on the part of (nearly) every gallery and artist to produce NFT works in the hope of putting up Beeple numbers. Just for reference, the most expensive work by Francisco Goya, Bullfight, Suerte de Varas (1824), sold for $7.4 million, and David Hockney, the most expensive living painter, saw his Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures) (1972) sell for $90 million. $69 million — that’ll buy a lot of GameStop shares. The gold rush has been on ever since, despite wild swings in NFT markets. Looked at from the second half of 2021, “sustainability” isn’t the first word that comes to mind when one considers NFT volatility. One could be forgiven for imagining that frequent enquiries were made to galleries about NFTs by a Mr. Moe Muss or one of his emissaries.

Sustainability is certainly not a word to use idly in relation to NFTs. NFT production, and, crucially, NFT maintenance, present major environmental concerns. A recent study by the Netherlands’ Central Bank estimates that Ethereum, one of the blockchain’s favorite media of exchange, uses twenty-seven million tons of CO2, compared to three million for the existing global card payment system. Ethereum’s carbon footprint is itself dwarfed by that of Bitcoin, which emits (at the time of writing) a staggering sixty-four million tons of CO2 per annum. New models of NFT hosting and maintenance have attempted to escape the grotesque energy profligacy of the current model, replacing the gluttonous energy demands of “proof of work” verification, wherein computers exhaust themselves solving mathematical problems, to a “proof of stake” model in which participants use their preexisting investments in a system to validate future transactions. Markets, at present at least, remain much more in thrall to the more wasteful proof-of-work system despite the existence of “cleaner” methods. Whoever wins the NFT lottery, the joke may be on all of us.

If environmental sustainability is an issue, what of professional sustainability? Over dozens of conversations in Berlin and London after the Beeple event, I heard artists talking excitedly about creating NFTs, and was even approached more than once about making one myself. Looking back to those heady first days, we can now say confidently that the first NFT gold rush was a bubble. How could it not have been? The idea that an artist who few outside of the meme-art community cared about before February could suddenly command numbers that would make the Picasso estate blush was inevitably going to draw all and sundry into its gravitational pull. But that sale was about as representative of the future trajectory of NFTs for artists as Jeff Bezos’s space jaunt is of the average person’s summer holiday. Immediately after the sale accusations of what finance professionals call “painting tape” — sales where buyer and seller in a transaction are suspiciously proximal — began to fly. Whatever the truth of these accusations — $69 million transactions are often sufficiently opaque as to ensure claims of painting tape are never provable — the siren song of a more democratic art market has outrun any suspicion that the NFT hubbub will result in a concentration of more power to the Beeples. As Momus might have said, when there’s a gold rush, your safest bet is to sell shovels.

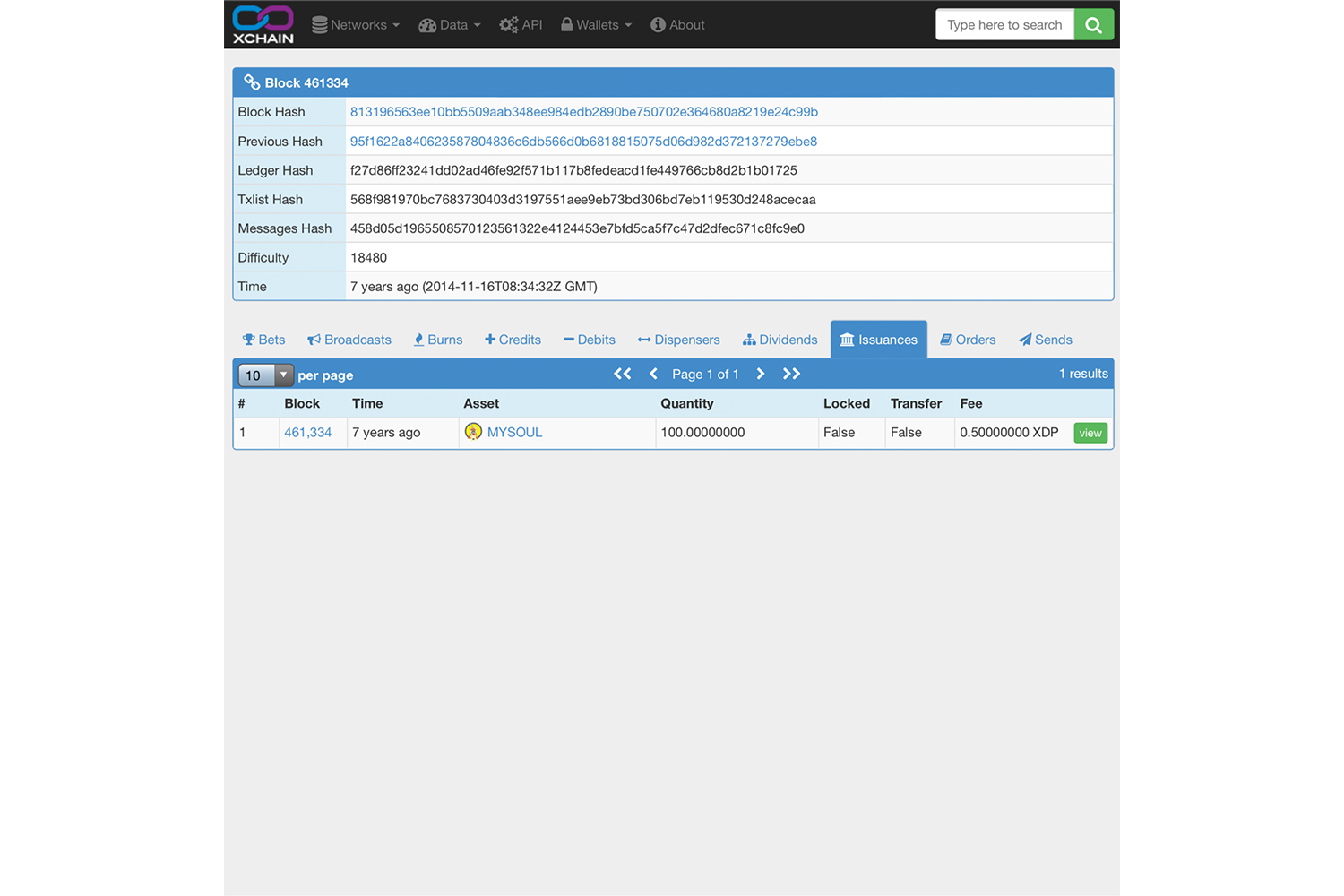

One must remember that the roots of the NFT as a medium for visual cultural production stretch back eons in web years to the pre-2015 period. Blockchain-based pieces like Kudzu and game works like Satoshi Dice and CryptoKitties have blazed a trail for crypto creativity, but the visual culture of today’s message board moguls is rather different from that of Robert Scull, or even Charles Saatchi. The primary market for NFTs before the Beeple Age was in the trading of images akin to Top Trumps or sports cards. Pixelated CryptoPunks for example — one of which was recently acquired by ICA Miami — and the notorious Rare Pepes of r/The_Donald fame/infamy were exemplars of NFT visual culture prior to the partial repositioning of the market for contemporary art. This “trading card heritage” is still present in the robust market for images of sporting achievements among NFT buyers. To acknowledge this is not to say that contemporary art has no future in the NFT world, but that the visual cultures that surround NFT production and circulation, into which contemporary artists are entering, have their own protocols and mores, some of which don’t easily connect with those that predominate in fine art.

Lately, contemporary artists who might have once thought NFT stood for “non-flammable turpenoid” have appeared at the crypto altar to pay tribute to whatever gods of laughable wealth the digital pantheon affords. But what can contemporary artists who practice outside the meme-sphere expect from their nifty tomorrows? Interventions by contemporary artists into the NFT sphere have had mixed results. That scrappy young upstart Damien Hirst’s characteristically vertigo-inducing intervention The Currency (2021) raises the question of who is power-trolling whom more than any serious aesthetic or conceptual questions. The work allows purchasers the choice of holding a physical artwork by Hirst or opting to retain an NFT of the image. When the choice is made (or not made) following a grace period of two months, one of the two works is destroyed. Speaking to the Financial Times, Hirst is quoted as saying, “Art as currency, a lot of people have problem with that.” Ironically, not as many people as have difficulty with the idea of cryptocurrencies as currencies. Investment firms including Goldman Sachs are increasingly holding crypto positions; but, in doing so, they treat crypto holdings as assets rather than currencies. Currencies exist to make payments, not as stores of value. Ask anyone caught up in the ridiculous Trump-inspired Iraqi Dinar scam of a few years ago how treating currencies like assets has worked for them. But to return to Hirst’s assertion, art as an asset, a lot of people, even some artists, have a problem with that too.

The fundamental problem of the NFT rush is perhaps best expressed by Seth Price in an interview with the curator Michelle Kuo for MoMA’s (not Momus’s) website. “The most important thing to know about NFTs is that NFTs themselves are just contracts.” Price’s observation is further contextualized by Wassim al-Sindi and daniel shinbaum [sic], the conveners and self-styled “janitors” of the 0x Salon, a Berlin-based salon discussing various topics in the nexus of blockchain/crypto culture and creative practice. In the 0x Salon’s inaugural podcast, al-Sindi and shinbaum discuss where “the work” lies in an NFT artwork. Asked by shinbaum whether the artwork is the visual image or the token, al-Sindi, a trained physicist and longtime observer and participant in the crypto culture, is crystal clear: “The token is the artwork.” To buy a token, then, is merely to buy a token, not necessarily what it purports to point to. What you see may be what you get, but it’s beyond the scope of an NFT dealer to guarantee how long you’ll be able to see it once you’ve got it. The medieval Momus Brothers’ pig market stall can be found just to the left of the Wreck of the Unbelievable.

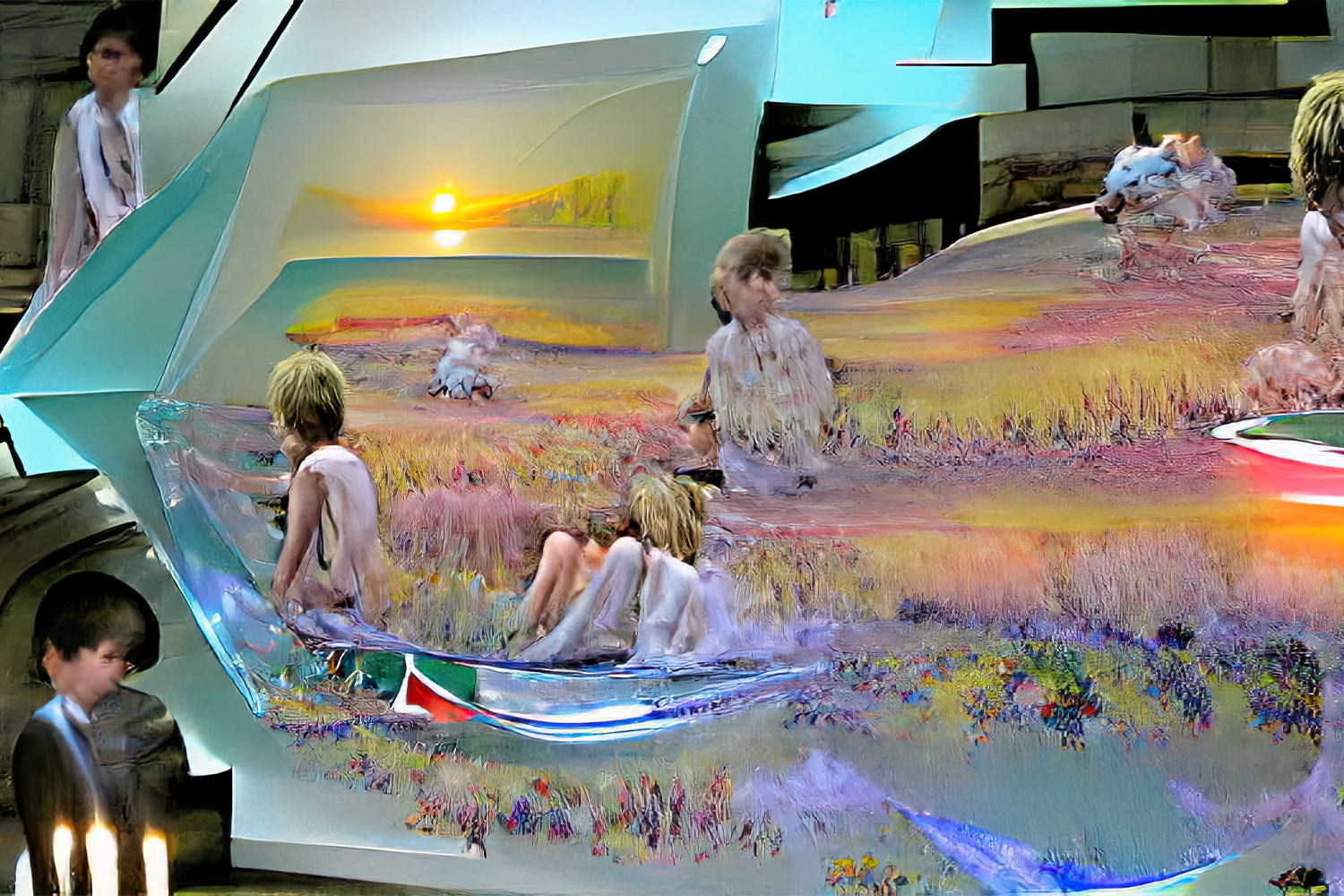

It is work by artists like Lina Theodorou, Rhea Myers, and Holly Herndon, all of whom are steeped in crypto cultures and forum discourse, who have produced, to my eyes at least, the most convincing NFT “fine art.” It is notable that prior to her NFT collaborations, Herndon, for example, was best known as a musician (she almost certainly will continue to be, as the market remains much larger for music, even now, than for NFTs — a salient, if easily forgotten, point). Her “Crossing the Interface (DAO)” (2021) series with Mat Dryhurst has an immersive and ethereal quality that transcends message board visuality, but it is also rooted in a visual ecology that is instantly recognizable within the cultural idiom driving NFT aesthetics. Indeed, Herndon, and provocateurs like Burnt Banksy — who burned a print of Banksy’s Morons (2007) and then made an NFT of the ceremony KLF style — are perhaps more true to the anarchic spirit of the boards/crypto culture that birthed NFT markets than established blue chippers day trading on the latest artistic fruit machine. There may be some irony in valuing the discursive immersion of works like Herndon’s as a means of assessing the staying power of NFTs, but art’s value, particularly its lasting value, is ultimately generated by communities, and whatever legitimacy a work may be said to have, either as a result of its aesthetic or its discursive consequence, can only be adjudicated truly by the audience it seeks to address. That NFT art, or at least NFT visual culture, has a future seems certain; the question is whether and how NFT visual culture will shape the contemporary art it embraces rather than vice versa. Crypto values may or may not translate into monetary values, but that has long been a hallmark of crypto culture, creating new facts and challenging the rest of the world to reckon with them.

The overwhelming question for most artists, no doubt, remains whether NFTs will provide a way to make a living, or at least survive creatively in an increasingly stratified and unequal art market. Unfortunately, the present circumstances offer more hype than hope. Art markets are intrinsically elitist, with studies showing that when overall income inequalities increase by one percent, fine art prices increase by fourteen percent. Even today, after the gold rush, most NFTs that sell which are not connected to sports imagery are traded for very low prices, more suited to buying lunch than buying restaurants. The allure, however, remains in place, and undeniably crypto assets and blockchain technology are increasingly being integrated into contemporary economic life — a process sure to accelerate as financial technology (FinTech) firms advance into emerging economies. The growth of crypto is sure to license more experiments in token-based value creation, but such value creation is almost by definition going to be limited to a certain elite of blue (micro)chip artists whose auction prices have to be protected. If you’re a struggling young artist, the question of how to generate digital scarcity and to profit from it is unlikely to be your top priority. The NFT is here to stay, but it will stay on its own terms, living by the rules of a discrete culture, praying to its own gods.