The manner of autoreduction that Dora Budor has applied to the processuality of her “solo” exhibition in the project space Progetto in Lecce is twofold. In an attempt to enter a place, to understand it, to absorb it, and to rewrite its history, Budor abandons the idea of a solo show and reflects on a different curatorial modality to build an exhibition approach far from self-celebration, proceeding in fact by reduction: she reduces the presence of herself, of her own works, opening up a dialogue with different artists and practices. The result responds both to her vision of the place — experienced by Budor during a long residency period of about seven weeks — as well as the individual artistic identities that have experienced the place less.

Reducing her physical presence, however, does not diminish Budor’s authorship, which collectively enacts a transversal and visceral occupation of the building. This form of authorship — while relinquishing the focus on her own research — responds to the other side of the process, the one that literally fits the definition of self-reduction as a “collective gesture of protest against the measure of cost.”

Budor immerses herself in the place and its social phenomena, dwelling on the tobacco industry in Lecce in the twentieth century — then a substantial part of the city’s economy — in particular through the lens of female labor. The hands of the tabacchine women who folded and rolled tobacco leaves to produce cigars for export to the nation’s most expensive markets are imprinted in two metal work tables with conveyor belts, taken from an old, disused local tobacco factory. Sometimes visible, the traces on the surface of the belts hover in the main floor of the building, where Budor sets up the two tables, forcing them, not only in terms of size, into a living space far from their usual location.This operation creates friction on the place and its function, as well as on historical memory: on one of the two tables — of which we can observe closely only one of the sides extending from one of the rooms — the words “MARCIA” and “ARRESTO” in the typical font of the 1920s brings us back to the Fascist regime, to the dynamics of forced labor and how this affected the lives of working women. Budor also sets up a papier-mâché copy of the same tables, a conceptual operation that calls into question the presence of the original tables in those spaces, as well as the meaning of the copy, made with a raw material characteristic of the place, papier-mâché, traditionally used for the production of statuary recurring in religious processions.

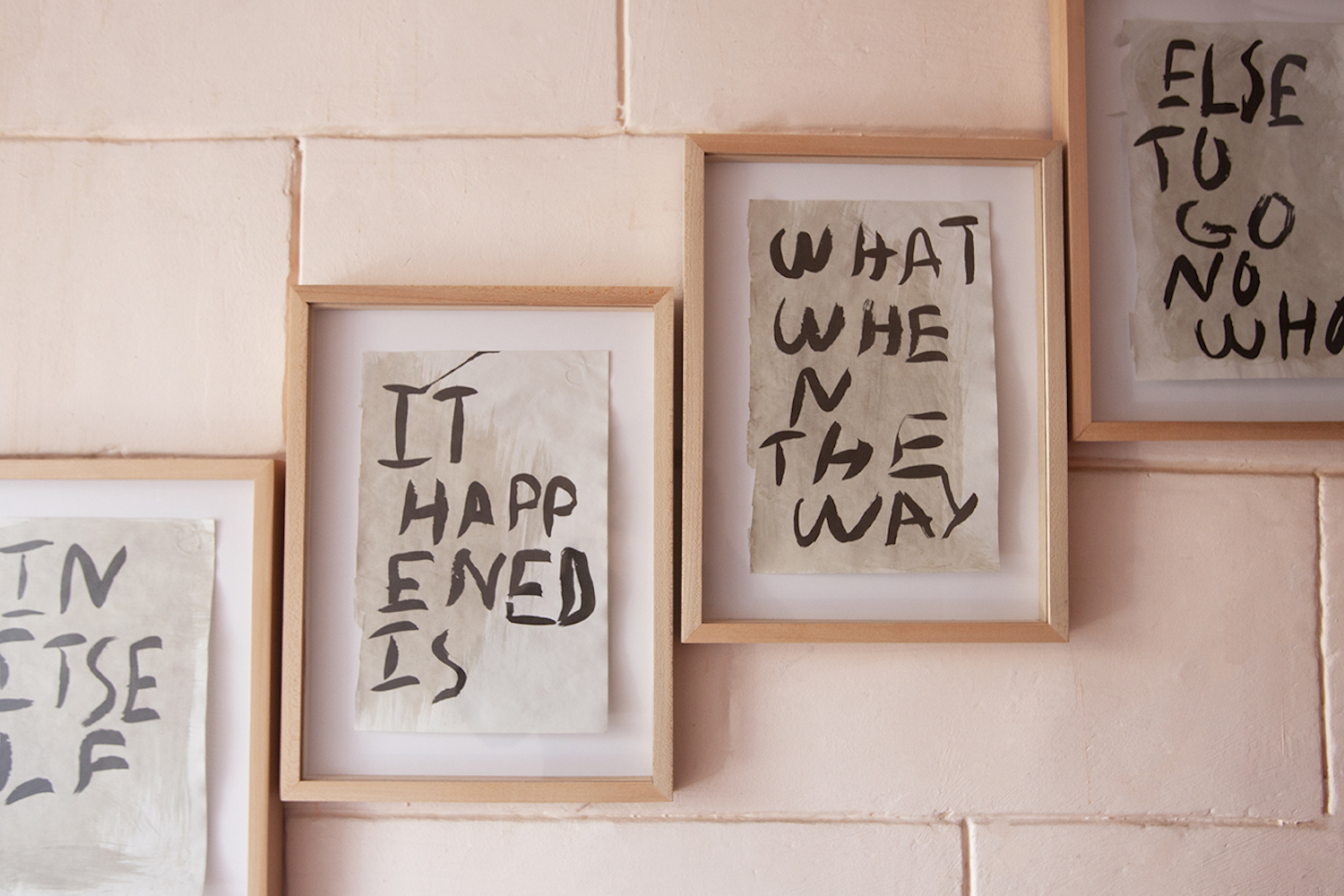

Budor’s gesture of collective occupation has to do with a personal and intimate dimension of occupying places and with the void left by the effluvia of those who have passed through. This haphazard emptiness unravels in Noah Barker’s partially opened beer bottles sealed with gold-plated aluminum — Constellation #2 and #3 (2021) — that echo the almost imperceptible constellations of dots (actually specific symbols of Italian industry) placed on the ceiling; and its transience is revealed in “Isn’t Anything” (2021), a suite of sculptures by Ser Serpas that almost entirely occupies the building’s open-air roof terrace. Serpas’s assemblages made of residue, abandoned objects collected in Salento, are fragments of reality and seem to have always inhabited that roof. They are in stark contrast with the skyline of Lecce’s white sandstone architecture and its ever-present palm trees, yet are completely consonant with the flip side of an industrial landscape, bringing to the surface problems of waste disposal and the limits of the capitalist system in Southern Italy.

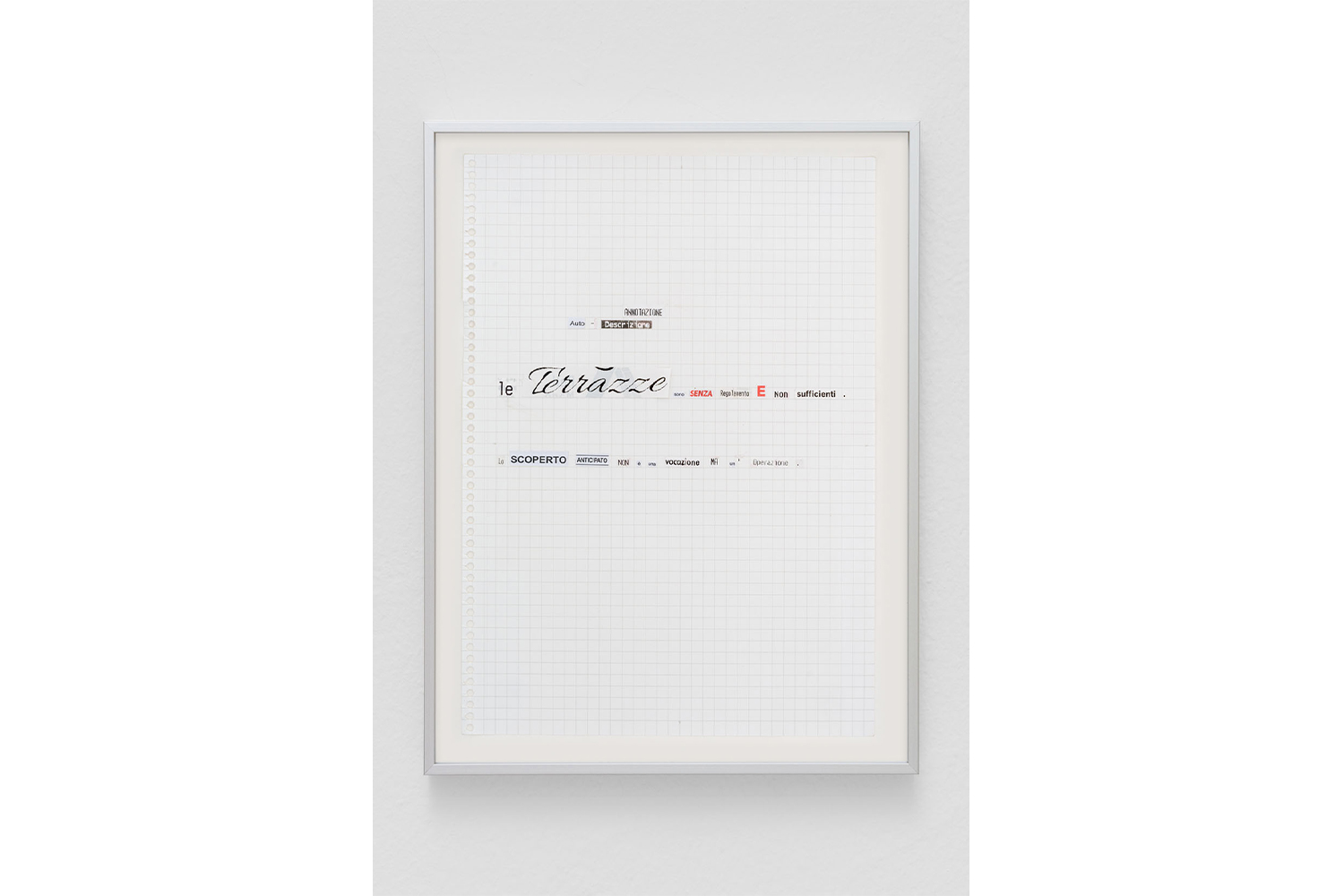

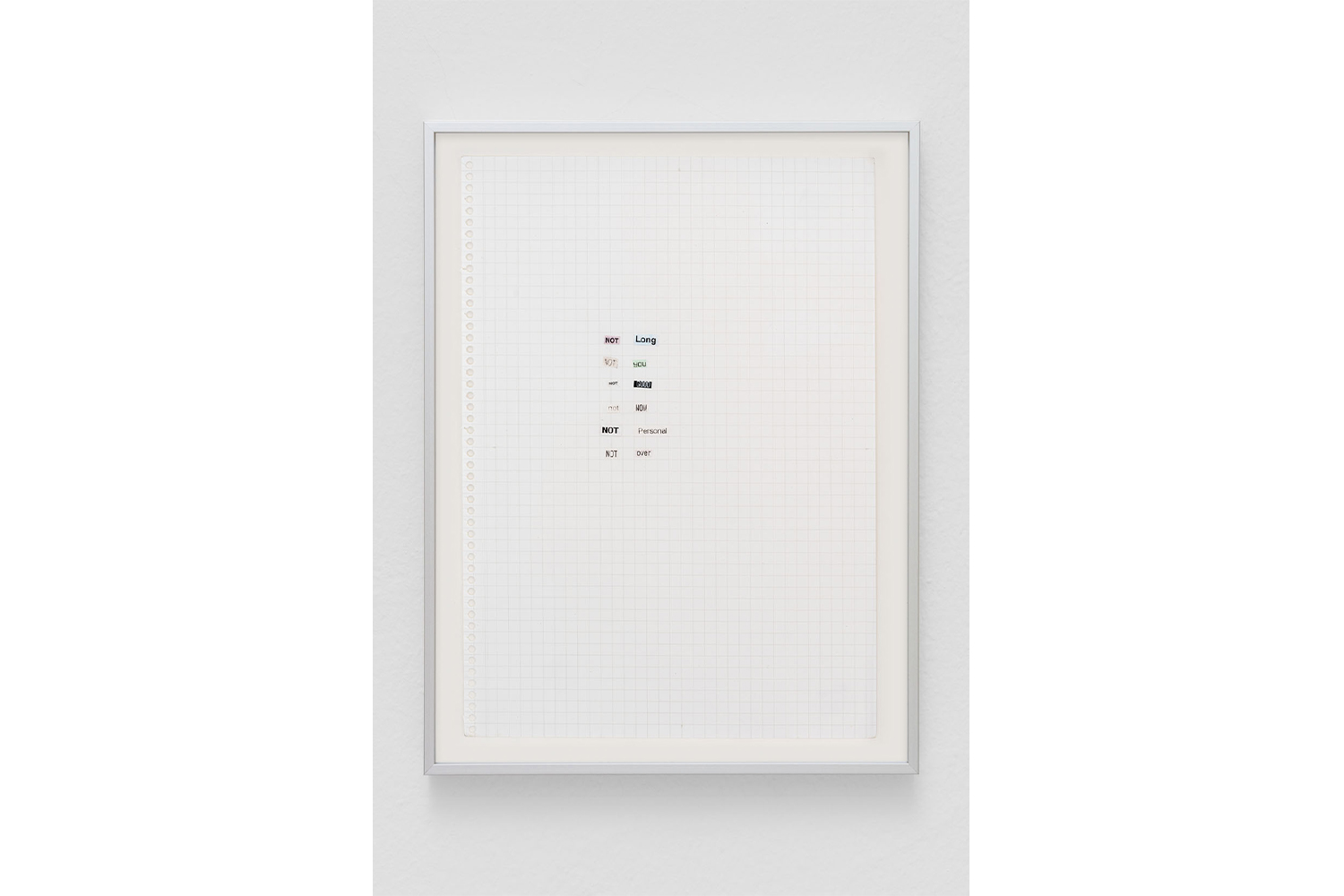

Emptiness is also the protagonist of Niloufar Emamifar’s intervention A Partnership for the Future on the relationship of human beings with the atmosphere and the current monetization of air rights; and in other ways by the two framed poems by Michèle Graf and Selina Grüter, the result of an incomplete “transcription” of the lecture-performance of Giovanna Zangrandi’s The Besieged Courtyard.

The inability to transpose from one language to another a painful reality, in this case the products of fascist dictatorship, is actually a symptom of a universal void common to humanity. We find this untranslatable void within Budor’s collective gesture amid the rooms of Progetto: a profound and always partial gesture.