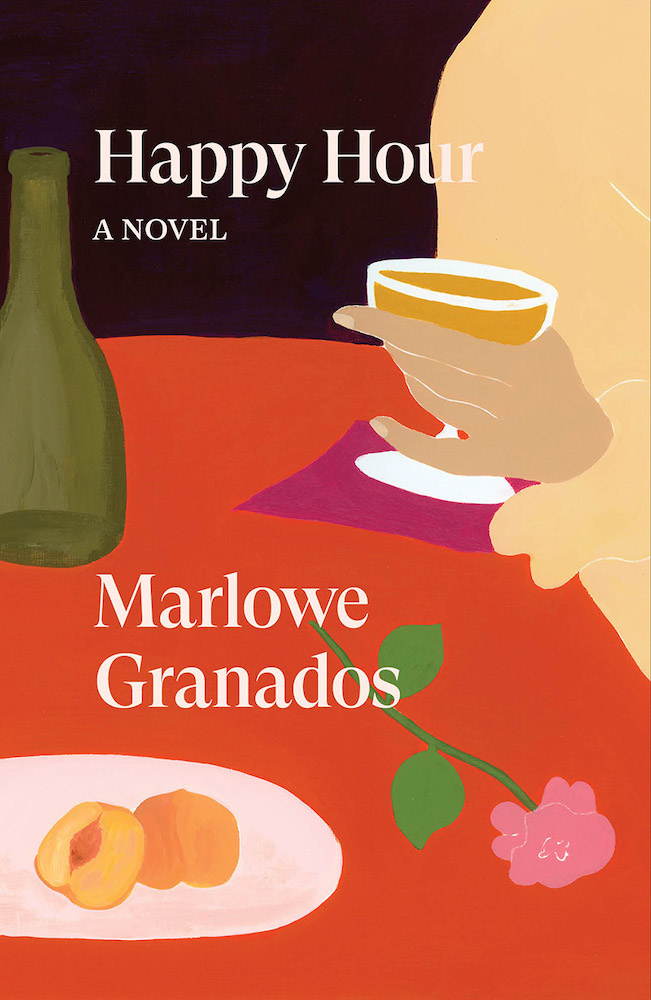

Amanda Luna Ballerini spoke with Marlowe Granados on the occasion of her debut novel, Happy Hour, recently published by Verso Books.

New York City during modern times. Two best friends, both twenty-one years old, come to the city to live a summer of delightfully hot despairing fun — on a budget, obviously. They navigate between various rendezvous, especially gallery openings. They flirt with celebrities and work as portrait models.

Marlowe Granados’s novel is a delight to read and to hear. Every word evokes a sensation from our lives that lingers with the turn of the page. We need this story more than ever. It is light, but it also speaks of loneliness, difficulties, yet always with an optimistic streak. The reader not only empathizes with but becomes one with Isa, the protagonist, and her flow of consciousness.

Happy Hour is about beauty and the essence of simple things, but also oysters and luxury and — why not? — the old-school fun of not knowing where the night will lead. Indeed, we are all currently experiencing a similar renaissance after the forced austerity of the pandemic. Like Isa, let’s put on the right look, go out, and take over the world.

Amanda Luna Ballerini: Your novel got me so nostalgic, thinking about a pre-pandemic era when everything seemed to be so simple. Reading it now was really the perfect timing — now that things are finally reopening. Does it make you terribly nostalgic too?

Marlowe Granados: The writing process for Happy Hour started when I was twenty-two. I had no understanding of that period as nostalgic, because when I started writing the book that special time had just ended and was pretty recent to me. I think it’s funny because to me 2013 didn’t feel specific at all: I was just twenty-one, and that’s what made it specific. Nostalgia is sometimes seen as the first sign of aging, and I don’t think it was ever part of the protagonist’s philosophy in the book.

Speaking for myself, I never wanted to be younger. The fact that these girls are twenty-one is kind of just a coincidence. “Ok, fine, we’re too young for something and too old for something else.”

ALB: Internet memes and contemporary catch phrases are also “paused” during the time of the novel.

MG: I felt that would make it so dated. It is set in 2013, but these girls could and eventually would exist in any time. People keep asking me about technology and the internet, and honestly I can’t think of anything worse to write about. Other people are certainly more interested and do it more justice than me. Me and my friends have always used the internet as a conduit to get somewhere. When I used to travel and was younger, I used it to know what parties were happening and which people were around. As easy as that.

ALB: Happy Hour reminded me in some ways of Sex and the City, but way more authentic, especially regarding money. Somehow Isa and Gala always manage to get the best of everything but with so much less.

MG: I remember being young and thinking Sex and the City was the first time I was hearing something so feminine and powerful at the same time. Me and my mother used to watch it and empathize with them laughing around a table. That stayed with me in some way for sure. What I really wished, though, was for my novel to live separately from the real world. It was mostly about creating a very sealed and elevated world. It is very much about the curation of its specifics and the details the characters see in it. Sometimes I wonder how the book would appear visually on screen, and I am sure it could not be filmed as a normal movie. It is something happening; it is real in a way, but it is still kind of a dream. Sequences rich in colors. Not something that happens in your suburb, but that could eventually happen. You know what I mean?

ALB: Do you think New York is still a setting for dreams to come true?

MG: I’ve been in and out of New York since I was fifteen, and I always had this kind of skepticism about it. I think it comes out in the novel, too. It’s maybe because I’m used to traveling and therefore never risked becoming “New York provincial,” which is a threat. There is a feeling that everything you do has a ripple effect when you live there, which is kind of true, yet there is this feeling of missing out all the time and being forced to be outside all the time. The pressure of constantly doing something is still very strong in the city. I can say I really teeter between business and lingering. But truly I like not having to do anything. I just wanna hang out with my friends, drink cocktails, and play tennis in the morning. I love to move around, and I have a very romantic inclination in the way I move, too. I’ve had my share of odd jobs, and I always knew how to find new money from other sources when I was broke.

ALB: Toward the end of the book you talk about a disastrous double date. You mention how some people like to call this bistro “a scene” — actually just everyone knowing everyone else and never getting outside of it. This happens so much everywhere. We need new exciting things, but somehow most events seem like a rip–off version of what already existed and with a more boring crowd. Do you think there are new ways we can create community that do not involve meeting friends at bars and calling it a scene?

MG: What happens to those scenes is that sometimes people are not welcoming of new people, and that is a problem. I’m so involved in the radius of where I live that for me it is kind of normal: I talk to everyone all the time. Now that the book is out I want to preserve more energy when having conversations, but still, having no limitations is key. I’ll talk to every weird and unusual person in the old-fashion way. People say that to me a lot and I enjoy it.

ALB: How do you image an art event (perhaps a gallery opening) in 2022? Has something changed? Aside from the fact that we still want finger food and free drinks.

MG: The point of today’s art events is that you are never there to really see the art. The fun thing is that the girls in the book become intertwined with the art world they roam around as sort of mirrors of the artists/people who attend. It is always about the dichotomy of the artist who feeds on these young women and creates this circle. I went to one recently and it felt so cliquish and not conducive to seeing the art. I highly recommend going when no one is there.

ALB: Do you think locations still matter today? It is weird because every city is peculiar but could be interchangeable, especially when we are talking about contemporary art.

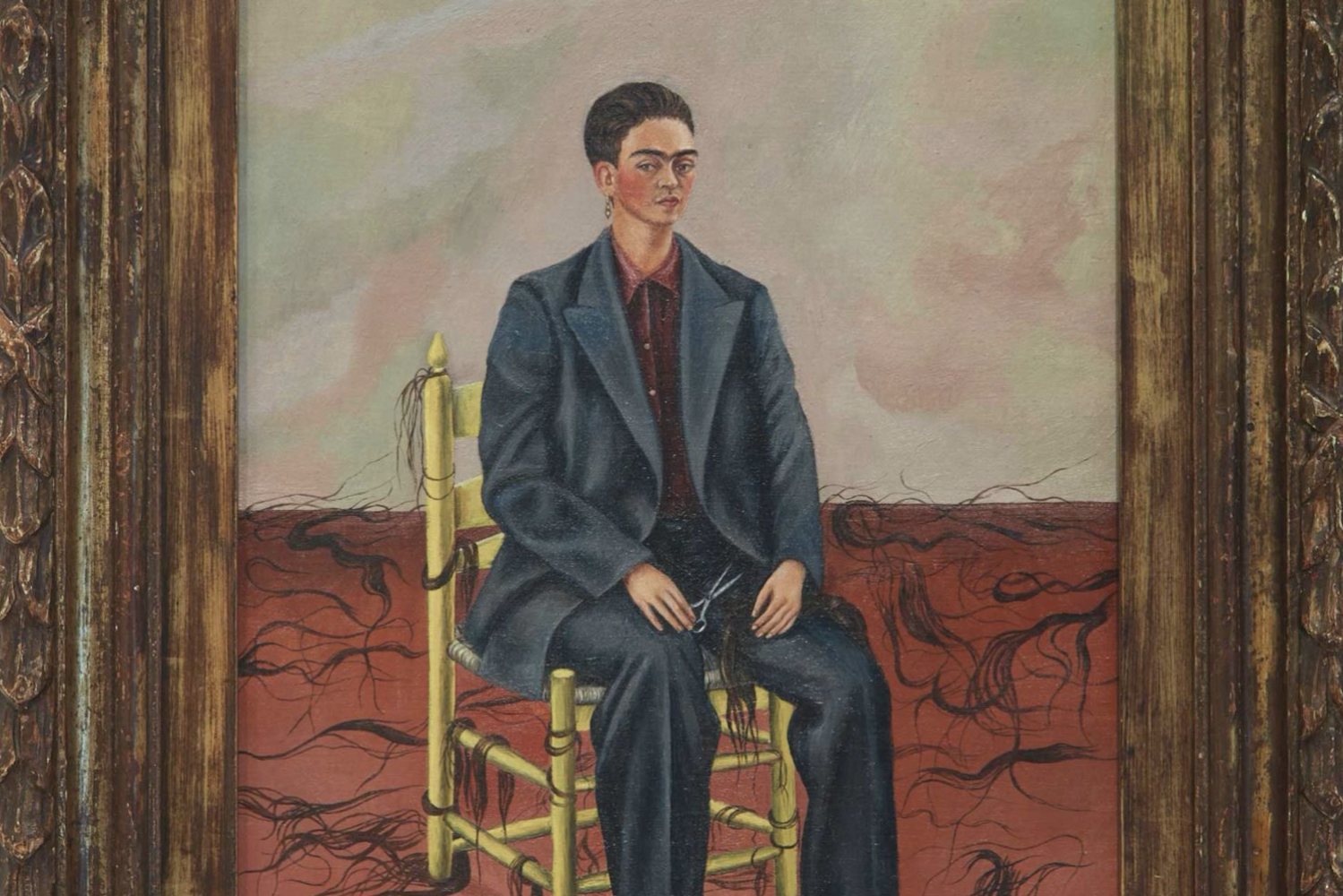

MG: I think scenes are mostly not so different from one city to another. I’ll bump into some people I met in New York and then see them in London or Spain. There are always these viveur travelers. What’s changed now is me as a person: it is very different to attend as a young woman no one expects anything from compared to when you’re even slightly more established. Both of them are not great. Since I did the first one I decided not live the second part. I already had a nice time and experienced what people want. It is pretty transparent. In the book I mention the concept of “owning your own image,” especially relative to being painted, since the girls model for artists. “I am in a painting,” but I have no control of who is consuming my image. Setting boundaries related to that it is important — to be able to tell your own version and vision behind every story.

ALB: “Civil dusk,” something you talk about in the book — which weirdly reminds me of the rayon vert talked about in the Rohmer film of the same name 1 is a time for thought and enlightenment. A sort of epiphanic time of day. Can you talk about it? I interpreted this time also as happy hour, or, as you might know, aperitivo in Italy, a huge part of the culture.

MG: It’s such a brief time frame. I learned so much about these different times of the evening surrounding sunset when I was writing about it. They are named after the last times sailors can sail home to shore and not be lost at sea. It is a very interesting, transient moment of the day, impossible to grasp. It gets earlier and earlier and later and later. It is actually a bluish light for me. Isa, in that moment, is having a particular reverie that has to do with a feeling born inside of her and coming from the city back to her too.

ALB: I resonated with almost everything you wrote in your book. As a Capricorn, I guess we resonate since you’re a Scorpio. I feel both these signs are there but not actually there. “Maybe we belong to different times,” as you said. What do people who belong to different times (and want to have a good time) need today more than anything else?

MG: We are surely missing out on glamour. True sensuality is also missing. We are really sterilized for some reason, and I often think of that. Charisma and charm are very much part of how I see things, but they seem to have disappeared on a greater level. The reason for that is perhaps thinking too much about people’s perceptions and how to seem a certain way. Seeing your life though someone else’s life is dangerous. I’ve always been a “yes” person, and hesitancy and restriction never help in having a good time. I wouldn’t advise that at all. Know your own art of living and you’ll create beauty and get pleasure. Snobbery is also annoying. My friends and I would go to dive bars, dressed as we fancied, and have the time of our lives. Restricting yourself is not glamorous. Being authentic is fundamental. I hope people will be more generous to one another — this has also been a problem. Collective empathy should effect positive change. Isa is a very generous and well-meaning person, and I thought about this a lot when writing from her perspective. It’s so much easier to answer with cruelty instead of being warm. Warmth is very glamorous.