Andrew Norman Wilson’s practice often interrogates the way in which artworks can infiltrate the viewer experientially. With In the Air Tonight (2020) he catalyzes the entrancing affects of pop music and Hollywood thrillers, repurposing their ready-made power to highlight the emotional susceptibility of consumers who long to be transported, however briefly — for the duration of a song or movie. The video makes palpable the dissociative effect of mass media, a simultaneous intoxication via emotional allure and detachment from the here and now. The ubiquitous Phil Collins track and the excerpted clips Wilson borrows from commercial cinema of the ’80s and ’90s operate anew, estranged from their original signification yet employing the substrate that continues to resonate inside us.

Aily Nash: Why this song?

Andrew Norman Wilson: There’s an urban legend about Phil’s inspiration for the song that I first heard as a teenager while getting high in a friend’s basement. According to the ritual of the legend, the song is played while a narrator tells the story, syncing the infamous analog drum break of the song with the climax of the narrative. A friend of mine performed this ritual especially well, and the legend stuck with me.

During the pandemic last year, the song was on heavy rotation across several stations owned by a particular media conglomerate. While driving on the Pacific Coast Highway one night, the song came on, and I noticed a woman who seemed to be lip-syncing along to it in the car next to me. Without hearing her voice, I watched her belt out the lyrics inside her vehicle, then thrash her arms along to the drum break before turning off the highway. She was, of course, tuned into the same radio frequency as me, but the uncanniness of her puppeting the song that was playing in my car seemed to resonate with the mysterious legend and my teenage friend’s masterful telling. For the past few years my work has emerged out of images or sounds I’m haunted by, so off I went.

AN: You made this video during the lockdown in the spring of 2020. What was your experience of movie-watching during this period, and how did that inform this work?

ANW: When lockdown hit I made my online movie archive public and started to expand it as part of my cinema project This Light. I was watching movies every day and processing hundreds of files, many submitted by This Light users around the world.

As I was writing my own version of the “In the Air Tonight” urban legend, I started to extract establishing and transitional shots from films made around the same time “In the Air Tonight” was released in the early 1980s; films with a neon noir aesthetic that could have featured the song on their soundtracks, like Hal Ashby’s 8 Million Ways to Die, Paul Schrader’s American Gigolo, or Brian De Palma’s Body Double, as well as more tangentially related films with clips that fulfilled narrative needs such as Fellini’s Toby Dammit, Ken Russell’s Altered States, and Robert Altman’s The Player.

AN: I imagine you might have wanted to avoid shots with actors so that the origins of the excerpts were less recognizable, but what did working solely with sequences without human figures do for the conceptual framework of the video?

ANW: At a certain point modernist painting and modern photographic media diverged. Painting became less reliant on the human face and even the human figure, while cinema and television have remained fixed on the face, usually in order to prescribe feelings for the audience (though the face is deployed distinctively as an abstraction in the work of Bresson, Costa, Weerasethakul, and many others). I often find the compulsion towards subjectivizing facialization to be not only a humdrum buttress for lackluster storytelling, but also a mode through which identity becomes overdetermined.

While the video — and Phil’s career as a whole — is bound up with notions of white male universalism (Slipperman, the narrator, refers to him as an “everyman”), its visual defacialization serves to intensify the dissociated identities within the text in order to complicate this universalism. In the end, we realize that Phil, Slipperman, and the stranger on the beach all coexist within the same body. The video can be framed as a point-of-view flashback in the manifold mind of Phil Collins within the fiction, but also in the mind of the viewer as a consumer of commercial cinema. This integration of an urban legend with shifty perspectives and multiple image sources amounts to an inviting collective hallucination. In other words, a movie, but more depersonalized than usual.

On a more practical level, this dissociation of the images from their sources allowed the varied clips to cohere within a new narrative, rather than acquiescing to referentiality, to origins. Cropping the aspect ratio to 4:3 gave me more longitude in this regard; I used several shots where, in the original, a character is seen on the left ⅓ of a 16:9 image. In cropping 4:3 images from wider aspect ratios, I was able to avoid questions like, “What is Al Pacino doing in this Phil Collins video?”

AN: Who is Slipperman, and how did this character come to be the narrator of the video?

ANW: The name comes from the Genesis song “The Colony Of Slippermen,” which to my ears is one of the most phenomenal displays of Phil’s drumming out of his entire career. Apparently “Slipperman” was occasionally used as a nickname for Phil by his bandmates, but it was Peter Gabriel who would get lowered to the stage inside a giant phallus, emerging in a beige Slipperman outfit adorned with swelling lumps, pimples, and boils.

In my narrative, Slipperman — a countercultural boomer whose references span Vladimir Nabokov to George Carlin — is Phil’s alter-ego, an identity more present when he was a member of Genesis during their headier prog rock days in the first half of the 1970s. While “Phil Collins” has since become a ubiquitous global superstar, Slipperman has retreated deep into the folds of Phil’s mind, still clinging to what some might call the “excesses” of progressive rock. The narration is written in his voice, and I feel this allowed me to combine the noirish urban legend with more florid embellishments.

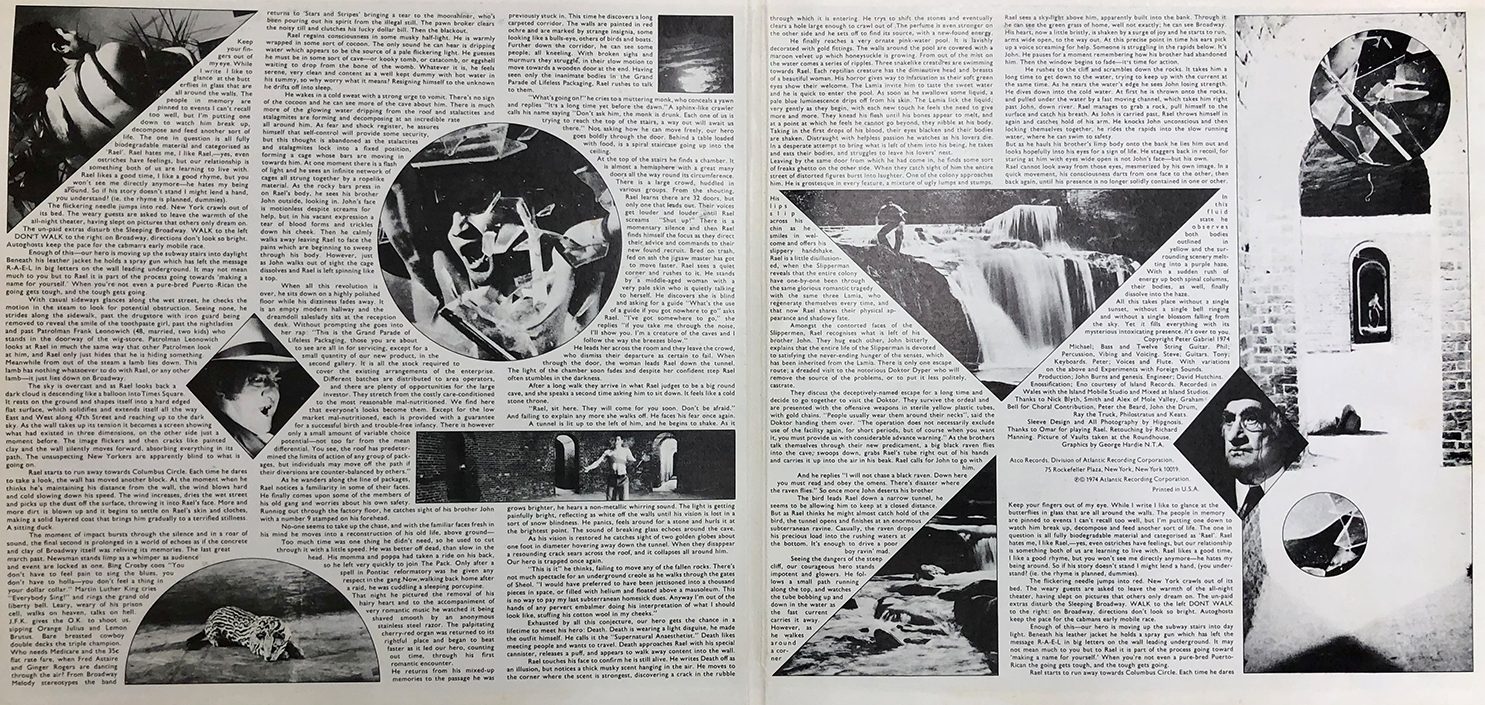

Slipperman doesn’t exist in any versions of the legend I’ve read, and I couldn’t find much more than a paragraph in summary. So I fleshed my version out to 1400 words, for which the nonsensical narrative presented in the liner notes of Genesis’s 1974 album The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway provided a lot of fodder.

AN: Can you talk about your interest in genre, and how film noir became the primary touchpoint for this work?

ANW: The first half of In the Air Tonight operates as a film noir due to the tone of the song and noirish qualities I could identify in the urban legend: a morally ambivalent protagonist within an oneiric, flashback-driven crime mystery narrated in the first person. I tried to adhere to the genre’s tendency to withhold poetic language so that the story could unfold procedurally, and allow for the poetry to emerge through the structural shift of the overall narrative, where at the end you realize that all three men at the beach that night were one. And so the plot closure aligns with the closure of Phil’s psychic imbalance, or at least his recognition of it.

Then there’s a genre shift to a more essayistic second half in which the imagery switches to an empty Malibu mansion — presumably Phil’s — though it’s actually appropriated footage of a mansion in Marbella, Spain, taken from real estate marketing videos (continuing the tradition of Spain standing in for the American West in cinema).

This sequence allows Slipperman to wax poetic a bit more freely about his own nostalgia for a particular moment in music history, while also reflecting on Phil’s Icarus complex and compromises of artistic integrity.

AN: The narrator speaks about surfacing in Phil’s head as an inner voice that questions his experience as an artist, asking: “Why do we make things?” Does this reflexive and perhaps ambivalent moment intersect with a shift you’re experiencing in your creative work and direction?

ANW: To be honest, I don’t really want to be a full-time “contemporary artist” anymore. The dream has continued to reveal itself as a delusion, as if I’m the unpaid intern of Andrew Norman Wilson and he’s been gaslighting me for a decade.

How did I pull it off for so long? For the basics, I’m on Medicaid, food stamps, and unemployment. I see the return policies offered by Bezos and the Waltons as loan agreements; I lend them $1500, and the interest they pay is my use of a new editing hard drive. While Turbotaxing I hallucinate a DJ software skin, transforming the expense estimate sliders into Fraud Modulator functions. Sometimes I sublet, but often I cat sit, dog sit, and plant sit — currently I’m caring for three sulcata tortoises, an iguana, two doves, and several koi pond inhabitants in Laurel Canyon. I accept unpaid exhibition offers from salaried curators and gallerists in far flung cities and tack on lecture stops at $150 a pop, spending as much time as possible as a guest in circulation, on sofas, so as to avoid paying rent anywhere.

After In the Air Tonight I shot a proof-of-concept short called Impersonator. It was made possible by the generosity of artist friends such as Gozie Ojini, Chadwick Rantanen, Asha Schechter, Alexandra Noel, and many others, and we worked alongside a seasoned Hollywood camera crew headed by Jesse Cain. The hope now is that it will lead to a feature and further work in the film industry. While I recognize the irony in shifting towards showbiz after making In the Air Tonight, I’m tired of working in a cottage industry that’s nearly impenetrable to all but those with advanced graduate degrees, or yachts. I want to make a perverse, shimmering, and irresistibly challenging action-thriller.